Полная версия

The Pike: Gabriele d’Annunzio, Poet, Seducer and Preacher of War

Within a year of his first book’s appearance, d’Annunzio, whose collected works were eventually to run to forty-eight volumes, had brought out two more. In Memoriam, dedicated to his grandmother, who had recently died, was published in May 1880, followed in November by a second edition of Primo Vere with forty-three new poems (throughout his career d’Annunzio was to repeatedly revise, re-package and re-sell his work). In each case Francesco Paolo paid the printer’s bills, but d’Annunzio himself was personally responsible for the books’ design. He was already knowledgeable about book production and literary business. Writing from his school desk to the printer, he fussed over paper quality and font sizes. He argued vigorously over the printer’s terms and negotiated a distribution deal with a local bookseller. As for the books’ promotion, father and son each did their part of the work. To celebrate the appearance of Primo Vere (second edition), Francesco Paolo gave a banquet on the terrace of the Villa Fuoco. Gabriele found a more ingenious way of attracting attention to the work.

Reading the English Romantics, he had reflected on the ways Keats’s and Shelley’s early deaths had left their names enveloped in a glimmering haze of pathos. It was a few days before Primo Vere’s second publication that the editor of the Florentine Gazzetta della Domenica received a postcard from Pescara, from an unknown informant (d’Annunzio himself), advising him that the ‘young poet already noted in the republic of letters’ had died suddenly after falling from his horse. The editor ran the story prominently. The news was picked up by papers all over Italy. In Turin the tragic death of the ‘last-born of the Muses’ was lamented. In Ferrara tribute was paid to the marvellous boy who was ‘the joy of his parents, the love of his friends, the pride of his masters’. The schoolboy poet had ceased to be someone spoken of only in the ‘republic of letters’. He had become a celebrity. He might not yet have achieved glory, but he had attained fame.

LIEBESTOD

A DAY OF TUSCAN SPRING SUNSHINE, a stream running between banks starred with flowers; nearby the cupola of a church glinting, tall cypresses rising above the walls of an ancient villa; in the background blue hills. Along the path comes a dark maiden: black eyes, black hair, black eyebrows, pale, pale face. A young man walks towards her. Days later he writes to tell her that he is hers forever.

It could be a tableau painted by Dante Gabriel Rosetti or Burne-Jones, prints of whose work Gabriele had seen in Nencioni’s rooms. It could be a scene from Tennyson’s Idylls of the King, or from Swinburne’s Laus Veneris (In Praise of Venus). Gabriele had been reading both poets. It was in fact the meeting of two flesh-and-blood teenagers as described by one of them: d’Annunzio, in Florence for the Easter vacation before his last term at school, falling precipitately in love with the seventeen-year-old daughter of his favourite teacher.

It wasn’t his first erotic experience, but it was the first of his romances. In d’Annunzio’s case the ambiguous word is the right one. All of his love affairs were at once real relationships – carnal and ardent – and literary creations. Vivere scrivere was one of his mottoes – ‘To live to write’. Sexual experience especially fuelled his creative energy. Looking back years later on his first kiss, he wrote that it was ‘the very moment when my life began to be my art and my art began to be my life’. In love, he reached for his pen.

The black-eyed girl by the stream was Giselda Zucconi. Dark-haired and heavy-jawed (like Gabriele’s mother, like several more of the women he would love), she was unusually well-educated for a girl, and a competent pianist. Her father, Tito Zucconi, taught modern languages at the Cicognini, and had become yet another of d’Annunzio’s mentors. Zucconi was a dashing figure, a teacher very different from the ‘greasy-handed priests’ about whom d’Annunzio wrote so contemptuously. He had fought alongside Garibaldi: he was himself a poet. He befriended the brilliant student, took him for long walks on days off and invited him to visit his family in Florence.

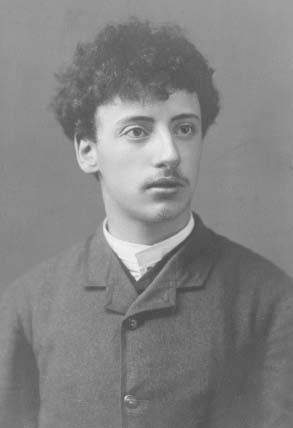

D’Annunzio, looking back regretfully in middle age, describes himself as he looked then: ‘the brow smooth beneath the dense mass of dark hair. The eyebrows drawn in such a pure line as to give something indefinably virginal to the melancholy of the big eyes. The beautiful half-open mouth.’ Self-regarding as it is, the description matches the photographs. Giselda was entranced. D’Annunzio had begun writing short stories set in the Abruzzi, heavily influenced by Guy de Maupassant and Giovanni Verga. On his second visit to the house he read Giselda one of them, a morbid tale involving a dumb beggar and the frozen corpse of a little girl. When he first encountered Giselda walking by the stream he had felt ‘an I-don’t-know-what’. When he saw her eyelashes wet with tears as she listened to his story he decided it was love.

He returned to school. Back in Prato he confessed his love to Tito, who gave him permission to write to Giselda. Within days she had told him she loved him in return. In the school dormitory d’Annunzio stayed awake until dawn, kissing her photograph and writing her long letters. Sometime he expressed himself as any teenager might: ‘I am happy, happy, happy.’ Or, ‘I love you, I love you, I love you.’ Sometimes his letters show how unusual he was. ‘Kiss me Elda, kiss me. Thrust your little hands into my hair and hold me nailed down and quivering like a leopard enchained.’

D’Annunzio’s erotic career began early. As the smartly uniformed boys of the Cicognini marched around Prato he was much inclined, so one of his teachers noted, to turn and stare at passing young women. Spending his school holidays with family friends in Florence, he escorted the daughter of the house (aged seventeen to his fourteen) to the Museum of Archaeology and kissed her in the Etruscan Room, falling on her mouth (as he recalled years later) as ravenously as a famished labourer might fall on food at the end of a day’s hard work and thinking – with a kind of delirious horror – about the other secret ‘mouth’ beneath her skirts. On a school trip he slipped away from his teacher, and sold his grandfather’s gold watch to pay for his initiation by a prostitute. That summer, sixteen years old and allowed home at last, he flirted with several young ladies in Pescara’s polite small-town society, and – according to his own later account – raped a peasant girl who struggled and babbled and shook with terror as he hunted her down in a vineyard and knocked her to the ground.

By the time he met Giselda two years later his craving for sex had become entangled with an appetite for suffering and with fantasies of death. It was the sight of Giselda’s tears that had first fired him with love. ‘I want to make those tears fall again,’ he wrote to her. He imagined she would be sobbing, frantic for a word from him. He luxuriated in the idea of her unhappiness. He even told her how much he would like to see her corpse. He loved it that she was deathly pale, like ‘the Blessed Damozel’, the dead girl of Rossetti’s famous poem and painting, but he would have preferred her even paler. He told her that he would go around all the florists in the city, fill a carriage with assorted flowers, and come to bury her beneath them. ‘Yes! To bury you! I want to make you die!’

He wrote to Tito Zucconi, not, as one might expect, promising to cherish and protect Tito’s daughter, but announcing: ‘I and Elda cannot live long.’ Both he and Giselda were, so far as we know, in perfectly good health, yet d’Annunzio wrote: ‘Our cold bodies will fall to the earth to feed the flowers; and we will be swept away, unconscious atoms, in the irresistible currents of the universal force.’ D’Annunzio had not yet heard Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde (on which his novel The Triumph of Death would be a variation) but the fantasy of Liebestod already possessed him. ‘If you were here now,’ he wrote to Giselda, ‘we would kill each other … Don’t you feel all the tragic terror of this passion?’

Letters began to pass between the young couple almost daily. She sent him her photograph and pressed flowers (her father acting as emissary). He sent her words, thousands upon thousands of them (around 500 letters in under two years). This was a love affair all made of words on paper. D’Annunzio wrote proudly to Chiarini, only six days after he had met Giselda, that he had found his ‘Beatrice’. So d’Annunzio was the new Dante and poor Giselda had been assigned the role of the girl whom Dante (if his poeticised account of their meetings is to be taken literally) laid eyes on only twice, who inspired his poetry and personified his ideal, but in whose actual life he played no part at all.

D’Annunzio set about remaking Giselda as an accessory suited to his own self-image. He deplored the conventional pose (‘so, so common’) of the photograph she had given him. He wanted her to look like a ‘proud and pensive queen, on the arm of her poet’. He renamed her (he would give all his lovers new names). ‘I want to call you Elda,’ he wrote. The name was more caressing than the full-length Giselda, more fitting for the child he wanted her to be. ‘You’re not a great big woman,’ he wrote. (He was to address many of his lovers, even when they towered over him, as ‘Little One’). He called her ‘bimba’ (baby), and imagined nursery scenarios, in which she played a petulant child. ‘It’ll do you no good to stamp your little feet on the ground … Come Elda … Baby, little pretty pretty pretty one. Forgive me? … You’re laughing, aren’t you?’ But if he liked to infantilise and dominate her, he also liked to be dominated. He told her that she was ‘bad’, ‘wicked’. He instructed her to wear black. ‘I detest, detest, detest pale colours on a woman.’ It would set off the pallor of her skin and it was appropriate to the other role he had assigned her, that of a ‘witch’, like Keats’s ‘La Belle Dame sans Merci’ or Tennyson’s Morgan le Fay.

Term ended, the young lovers could at last meet for the first time since they had declared themselves. ‘What happy hours we had yesterday!’ d’Annunzio wrote to Giselda the next day. ‘Do you know that for twelve hours we were always in each other arms, always kissing with those long long kisses which made us tremble in every limb, always whispering those soft words?’ Of course she knew, but for d’Annunzio an experience was insubstantial until he had written it down. During the eleven days he stayed in Florence he wrote several of the lyrics which would appear the following year in his next collection, Canto Novo, with its dedication to Elda, ‘the great the beautiful the most adored inspiration’. By the time he left for Pescara he considered himself engaged to her. Tito, who knew that his daughter had caught the eye of an exceptionally talented boy, made no objection. D’Annunzio confidently told both father and daughter that his own parents doted on him. They would agree to anything that would make him happy. And so off he went to Pescara.

In his first novel, Pleasure, d’Annunzio describes his hero, Andrea Sperelli, anguished by his bewitching mistress’s sudden and inexplicable announcement that she is leaving him. She stops her carriage. He descends. He is in despair. ‘What did he do, once Elena’s carriage had disappeared in the direction of the Four Fountains? – Nothing, to be honest, out of the ordinary.’ Sperelli goes home, changes into evening dress and goes to a dinner party, not apparently to give Elena much thought until they meet again by chance two years later. Sperelli is by no means a faithful self-portrait of his creator (he is very much richer and more aristocratic), but author and fictional character have a great deal in common, and this trait is one they share. There is no reason to suppose that d’Annunzio was cynical in his treatment of Elda. He was, for a while, in love with her. He probably really thought of marrying her. And yet, once he had left Florence, he doesn’t seem to have missed her very much.

Life was sweet for d’Annunzio that summer. Eighteen years old, finished with school at last, he was poised to enter the adult world where his reputation, going before him, would guarantee him a welcome. Returning to places he loved and a growing circle of entertaining friends, he enjoyed a long, delicious and productive summer by the sea. His family were gratifyingly proud of him. Francesco Paolo had had the titles of the poems in Primo Vere written into the frescoes on the drawing-room walls. He was working fast, writing the stories of peasant life that would be published the following year in Terra Virgine, and more poems for Canto Novo. He was also enjoying himself. He rode, he swam, he went boating by moonlight.

His letters to Elda are full of tactless hints of how full and merry his life was without her. People burst in on him while he’s writing to her. ‘Curses! There is an absolute eruption of friends in the room … Forgive me if I leave off … They’ve taken all the foils and sabres out the rack and they’re making the most awful din.’ (Then and later, d’Annunzio loved to fence.) He was doted on and fussed over. Preparing for a trip, he reported that his mother, his three sisters and his two aunts were all in the room helping him to get ready. When he wanted other female company the resort town of Castellamare, just the other side of the Pescara river, provided – by his own account of the following year – plenty of diversions. There were bathers on the long sandy beach, and on the promenade ‘what vaporous floating of veils around women’s heads! What feline flexibility of bodies confined by the arabesques or flower patterns of an outfit à la Pompadour! … What flurries of young laughter ringing out from beneath big hats laden with flowers!’ The Abruzzese journalist Carlo Magnico would describe d’Annunzio bobbing around a group of such young women ‘cocky as a wagtail’. As dapper as a glossy little bird, preening under the attention afforded a local hero, full of energy and self-love, he enjoyed himself while Elda pined.

He had been wrong, as it turned out, to assure her that his parents would consent to their engagement. His father, especially, was far too proud of him to welcome the idea of his committing himself so young to marrying a mere schoolmaster’s daughter. Somehow it was settled that, rather than enrolling at the University of Florence, where he could have continued his studies while seeing Elda as often as the two of them pleased, he would go instead to Rome. How far Gabriele resisted the decision is unrecorded. Rome, the capital, was surely the place for an ambitious young man, and d’Annunzio was very ambitious indeed. Besides, his need to be with Elda does not appear to have been all that urgent.

He wrote to her daily; he composed poems celebrating her bewitching beauty. But when she suggested that he could perhaps make a scappata, a ‘jaunt’, to Florence to see her, he treated the idea as absurd. She has no idea of distances, he wrote. ‘You really think Pescara to Florence is a “jaunt”?’ Perhaps, he adds, he’ll stop off on his way home from visiting the Exhibition of Fine Arts in Milan. (He didn’t do so.) Elda might well ask why, if he was able to go to Milan, he should find it impossible to reach Florence, which was so much nearer. ‘If I can’t kiss you again I’ll die,’ he wrote, but still he allowed time to slip by without doing so. ‘Just think,’ he wrote, on the eve of his departure for Rome in November, ‘it is five months, five long, long months, since we saw each other’ – a fact for which he had no one to blame but himself.

Finally, at Christmas, half a year after their last meeting, he took the train from Rome to Florence to see her again, and stayed until Twelfth Night. By the time he left Elda’s mouth was sore and swollen from all their ‘savage kisses’. There followed another six months, during which he assured her almost daily by post that he ‘was all yours, all yours, all yours for ever’. Giselda wrote again and again imploring him to come to her; but always there was some excuse. He had deadlines to meet; he had to sign the university register on a regular basis in order to avoid being called up for national service; his parents were coming to visit. On 15 April, the anniversary of their first meeting, he wrote lamenting his inability to be with her and elaborating a happy vision of their future domestic life. He will have a lovely bright study, he writes, full of pictures and antique weapons and rare fabrics, ‘and I will break off in the middle of a hexameter to come and give you a kiss on the mouth’. It is noticeable that he seems to have put more creative energy into picturing the room than into imagining her.) It is so hard, he says, that he cannot run to her. He seems to hear her crying out to him. And yet, he says, he cannot possibly visit her. He doesn’t explain why not.

Two weeks after writing that letter he went to Rome’s railway station with two friends who were on their way to Sardinia. He intended only to see the others off, and then on an impulse, he went along too, declaring he couldn’t pass up the opportunity of seeing the full moon rising over the sea. He was wearing a white rose in his buttonhole and carrying nothing but a cane with a lotus-flower handle. (For aesthetes of his generation, the lotus, the ‘sceptre of Isis’, was both a phallic symbol and a kind of shorthand for all things Orientalist and exotic.)

The trip was hilarious, its planning shambolic. On the train the young men fell in with some aristocratic acquaintances in hunting gear, who were going out to the marshes to shoot quail. Much jovial talk, then, once the huntsmen had got out, the remaining three lay full-length along the seats, dangling their feet out of the window. At Civitavecchia, where they were to embark, d’Annunzio dithered. First he said that he wasn’t going any further, then he said he’d come but wandered off and ordered a vermouth in a bar, thereby nearly missing the boat. That night, at sea, he began by strolling on deck, jotting down notes for an ode on the moonlight. The weather changed. A wind got up and he abruptly turned first yellow, then green and went below, where he spent a miserable night retching and shivering in his linen suit.

The trip to Sardinia began as a boyish lark, but developed into a mind-altering experience. The friends visited the mines at Masua, and d’Annunzio wrote a powerful account of the hellish conditions in which the miners lived and worked. They went down into the lightless, foul-smelling tunnel, where ‘the hot viscid mass of vapour embraced us; we felt it on our faces like a soft, wet tongue; it seemed as though two hands drenched in sweat were wringing our hands’. He wrote to tell Giselda about it, but she – poor girl – was struck only by the fact that he had been free to leave Rome at a moment’s notice for a three-week trip, while declaring himself unable to spare even a day or two to be with her. The following month he was with her in Florence for ten days before going onto Pescara for the remains of the summer. There he named a rowing-boat Lalla, but the frequency of his letters to the real Giselda dwindled. In February 1883, he wrote to her for the last time.

D’Annunzio was rapidly to acquire the reputation of a Don Giovanni who seduced and deserted his women without a qualm. In fact he always found it immensely hard to take his leave. It was partly that he was chronically indecisive: his havering on the quay at Civitavecchia is characteristic of the man. And it was partly that he could say neither ‘no’ nor ‘goodbye’ to anyone. He never turned down commissions. He would agree to anything, and then default on his promise. Years later, when he was a great man plagued by fans or presumptuous ex-friends, he was incapable of bringing tedious conversations to a close. Instead he would mutter something enigmatic and leave the room. His visitors would wait, expecting him to return at any moment, but they would wait in vain. He found it dreadfully hard to dismiss a servant. When he was living on the French coast he once went to Paris (a day-long train journey) to avoid being present when his major-domo, on his orders, sacked his groom. Rather than give a straight ‘no’ to unwelcome invitations he would invent preposterous excuses: he once got his chauffeur to telephone his host for a lunch with the information he had gone up in a balloon and might not be coming down to earth for some time.

There is a further reason why his love affairs had such protracted endings. The more unhappy a woman was, the more interesting to him she became. The more he tantalised Elda with promised visits which were repeatedly deferred, the more adorable her image seemed to him. ‘You must be sad, immensely sad, my poor angel!’ he wrote. ‘You will be thinking of me with desperate desire.’ The idea of her disappointment – denied his ‘savage kisses’ – was one he liked to dwell on. Seeing her so seldom, he was really in no position to report on how pale and wan Elda really was, but he addressed her in a rapture of sadistic pity as: ‘My pallid Ophelia, my poor betrayed virgin.’ That he himself was the betrayer he seldom directly acknowledged. Instead he responded to her reproaches by becoming, or so he tells it, frenzied with grief.

The d’Annunzio who wrote the letters was as much a fictional construct as the girl to whom they were addressed. The Sardinian escapade ended with a scene that might have been lifted from Mozart’s Don Giovanni. D’Annunzio and his two friends, who had been overly familiar with the local women, were chased down to the ferry by a crowd of hostile male Sardinians. A comical (though probably frightening) episode, it gives us a glimpse of the real-life ‘wagtail’ d’Annunzio – a very young man strutting and flirting on a trip out of town. One of his companions on the voyage wrote: ‘He would be off and then, before he’d even been missed, he’d be back like a cat with a mouse in his jaws’ – the ‘mouse’ being a young woman.

Writing to Elda he was a very different person, palpitating with love and anxiety, frequently suicidal. ‘I am surrounded by a terrifying abyss,’ he wrote after she had threatened to break off their relationship. ‘I am alone on a pinnacle of rock. I see no light, I have no hope, you have taken everything from me.’ His very last letter must have been bewildering for her to read. ‘We love each other always,’ he writes, but then, ‘the memories disperse inexorably like empty dreams.’ He dwells with repellent arrogance on the unhappiness he’s caused her. The letter ends in a cruel sequence of contradictions. ‘Addio’, he writes repeatedly. He is sad, he says. To write more will only make her sad as well. ‘Addio’ again, but then ‘I kiss your mouth with a desire beyond words.’ More maddening pity – ‘Oh my poor martyr!’ Again ‘Addio, addio.’ And then finally, the by-now-evident-untruth twice affirmed: ‘Yours, always yours.’ He was just about to turn twenty. Four months later he was married, and not to Elda.

In 1921, after a silence of thirty-eight years, Giselda wrote to d’Annunzio asking for his permission to sell his letters. She hoped that they would fetch enough money to allow her son to marry. She was unusual among d’Annunzio’s women in having kept them so long. At the end of each of his subsequent love affairs he wrote his once-beloved woman a letter full of mellifluous expressions of regret for the fading of a great passion, but ending with a brusque request for the return of his letters. He replied to Giselda by suggesting she hand the letters over to his lawyer. He did not invite her to visit him.

HOMELAND

THE BOISTEROUS GROUP who burst into Gabriele’s room, making a distracting racket with the fencing foils, were not his only companions in the Abruzzi. A few miles south of Pescara, in Francavilla, lived the painter Francesco Paolo Michetti, who was to become the most loyal and generous of all d’Annunzio’s friends. Michetti was eighteen years older than Gabriele, old enough to become one of his extra fathers, and a successful artist. During the summers he was joined in Francavilla by a creative group of comrades who called themselves – with playfully blasphemous arrogance – the ‘Cenacolo’ (the word translates as dining club, or dining room, but in Italian it is most frequently used of the Symposium over which Socrates presided, or of Christ’s Last Supper). The most constant guests were Francesco Paolo Tosti, the composer who would later set many of d’Annunzio’s verses to music, and the sculptor Constantino Barbella.