Полная версия

The Pike: Gabriele d’Annunzio, Poet, Seducer and Preacher of War

He had found his métier. Romain Rolland, recoiling, likened him to Marat. He had become the figurehead of a mass movement. When he drove away from the Capitol, ‘dishevelled boys, their faces crazy, dripping with sweat as though after a fight’, threw themselves at the car, nearly lifting it off the ground. ‘The battle is won. The great bell has sounded. The whole sky is on fire. I am drunk with the joy of war.’

Quite how much political effect this extraordinary sequence of public demonstrations had is a matter of dispute. The Treaty of London had been ratified already, before d’Annunzio returned from France, but it is conceivable that without his intervention Salandra and his cabinet might have failed to carry the electorate (the majority of whom dreaded war) with them. But, whatever the extent of his actual influence, it certainly appeared to the public that d’Annunzio – a private individual without any constitutional authority – had imposed his will on the elected government, and that he was the man who had taken them to war. He had done it by directing a stream of virulent abuse against representatives of Italy’s democratic institutions, and by urging the crowds that gathered around him to begin what might have amounted to a civil war. If anyone in Rome in those frenzied days was an enemy of the state it was surely not Giolitti, but d’Annunzio himself.

Nietzsche defined the state as ‘a remorseless machine of oppression’, a ‘herd of blond beasts of prey’. D’Annunzio – who fancied himself (in some moods) to be a Nietzschean Übermensch (superman), unshackled by social conscience or civic duty – had no respect for the electorate, and no compunction about undermining the authority of democratic institutions. A decade later Mussolini would refer to the events of May 1915 as a ‘revolution’ and boast that in that glorious month the Italian people, incited by d’Annunzio ‘the first Duce’, had risen up against their corrupt and lily-livered rulers, clamouring for the right to prove their honour and gain glory, and that those rulers had ignominiously surrendered. The truth is otherwise. But the spectacle of a government apparently harangued into action by a demagogue with no respect for the rule of law was ominous for constitutional democracy.

Immediately after the fierce excitement of his appearance on the Capitol, d’Annunzio withdrew and walked, alone and quiet, on the Aventine Hill. The lovers in his novel Pleasure had ridden the same way, ‘with ever before their eyes the great vision of the imperial palaces set alight by the sunset, flame-red between the blackening cypresses, and through it drifting a golden dust’. So had d’Annunzio himself with Elvira Fraternali, the great love of his Roman years. He thought about her that evening (although he was to leave the letter she wrote him that month unanswered: he did not like to see what age did to women he had once doted on). He brooded over the five years of his ‘exile’ in France. To return to the city where he had made his name, and married, and several times fallen in love, and been young (he wrote that year that he would give anything, even Halcyon, his finest poem-sequence, to be twenty-seven years old again) moved him deeply. By the gate of the Priorato of Malta, with its famous view through a keyhole of the dome of St Peter’s, he saw what looked like a tiny star hovering at the level of his eyebrows. It was a glow-worm, the first he had seen since he left Italy in 1910.

In his notebook, in his letters, in his memoir Notturno, the glow-worm is accorded almost as much space as the preceding oration. D’Annunzio’s case has always puzzled those simple-minded enough to believe that artistic talent and refined sensibility are incompatible with political extremism and an appetite for violence. Only hours after he had been raving against his political opponents and urging a mob on to murder, he was strolling – pensive and nostalgic – through the jasmine-scented Roman night, his appreciation of Rome’s multi-layered beauty that of a man of deep erudition; his response to a minuscule natural wonder that of a poet.

On the day Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary, d’Annunzio dined with some of his supporters. Very late, as dawn was breaking, he spoke to them. This address makes a quiet, gravely ominous coda to the stridency of the public speeches. He looked forward to the ensuing carnage without compunction for his part in involving his country in it. He referred blasphemously to his days of non-stop oratory as ‘the Passion Week’. This was his night in the Garden of Gethsemane, the moment when he allowed himself and his hearers to feel the horror of what was to come. ‘All those people who yesterday were tumultuous in the streets and squares, who yesterday with a great voice demanded war, are full of veins, are full of blood.’ He had exulted in the idea of arriving at Quarto with a legion of sacrificial victims, ‘young blood to be spilt’. Now he looked forward to making the oblation of countless others’ lives to his ‘tenth muse, Energy’, who ‘loves not measured words but abundant blood’ and who was about to get her fill of it. He concluded with a muted prayer: ‘God grant that we find each other again, living or dead, in a place of light.’

Show over, d’Annunzio relaxed. In the summer of 1915, between his prodigious feats of oratory in May and his setting out for the front in July, he sank, according to his secretary Tom Antongini, into ‘the most abject state of frivolity’. He summoned Aélis from Paris to join him (Nathalie was pointedly not invited) and went, so Antongini tells us, ‘from a reception to a dinner and from an intimate tea to an even more intimate night’. As the forger of Italy’s new martial destiny he was the man of the hour: women found him less resistible than ever. D’Annunzio’s son Mario reports that a rich Argentinian lady took a room in the hotel expressly to be near him. (He accepted the flowers with which she presented him, but rejected their donor – ‘too thin,’ he said.) Isadora Duncan was there too, and perhaps more fortunate. His philandering did nothing to decrease his popularity with the public. His militancy added to his sexual allure; his sexual conquests enhanced his virile, iron-clad image.

He was not writing. Now he was a hero he was more marketable than ever, and the people he had hurried into war looked to him to compose their battle hymns. But no words came. ‘I have a horror of sedentary work,’ he wrote that summer. ‘Of the pen, of the ink, of paper, of all those things now become so futile. A feverish desire for action devours me.’

He had not, as a young man, shown much enthusiasm for the soldier’s life. He had been a resourceful evader of national service and, when he found himself unable to defer the evil day any longer, he served his country with extreme ill grace. ‘It is certain death for me,’ he wrote to his lover. ‘Ariel a corporal!’ (Like Shelley, one of the models for his own persona, he named himself after Shakespeare’s androgynous spirit.) ‘The delicate Ariel! Can you imagine it?’ He was obliged to live in barracks and groom his own horse. He left the army with relief. Now, a quarter of a century later, he was avid to rejoin it.

As he waited in Rome for instructions as to where he was to present himself he fretted over the difficulty of getting his uniforms made. Luigi Albertini, who was expecting a Song of War from him for publication in the Corriere della Sera, received instead a letter complaining about the difficulty of finding a tailor. Soon, though, he was wearing the elegant white outfit of the Novara Lancers, and experiencing curiously mixed feelings about it. ‘I already feel I belong to a caste, and that I am the prisoner of rules.’ He was to be attached to the staff of the Duke of Aosta – the King’s taller, more charismatic cousin who commanded the Third Army – and given almost unlimited licence to define his own war work. He had permission from the commander-in-chief, General Cadorna, to visit any part of the front and to participate in any manoeuvres he chose. He was to be, not a leader, but an inspirer.

His progress northward at the end of July was attended by almost as much excitement as his arrival in Italy had been. Minister Martini, who saw the pushy adolescent he remembered all too clearly in the world famous poet, wrote irritably that d’Annunzio would have done better to have gone directly and ‘in silence’ to the military base at Udine, ‘but he can’t live without réclame’. He went to Pescara to pay a farewell visit to his mother, who was by this time paralysed and mute, and was lavishly fêted by his fellow Abruzzese. He stopped off in Ferrara and presented the manuscript of his play ‘Parisina’ to the mayor in a public ceremony, declaring that he ‘carried the beauty of that city in [his] intrepid heart’. Martini wrote that this was ‘all foolishness which annoys the public’, but he was wrong: the public responded warmly.

As usual, d’Annunzio was spending money like there was no tomorrow – a natural response to the onset of a war perhaps, but one which was exasperating to Albertini, who was acting as his unofficial manager and saw all too clearly how close d’Annunzio was coming to another financial catastrophe. He was unable to settle his bill at the expensive Hotel Regina where he had stayed for two months; nearly three years later he was still trying to retrieve the trunks full of clothes and knick-knacks he was obliged to leave there in lieu of payment. He had to beg his book publisher, Treves, for an advance to pay for the two horses which, as a cavalry officer, he was expected to provide. Now Albertini urged him to go straight to the Duke of Aosta’s headquarters: good sensible advice. ‘There you’ll eat regular meals for four lire a day. Perhaps you won’t need to pay for lodging. They’ll give you 400 lire a month. See what horizons open up!’ Not the kind of horizons that drew d’Annunzio. On arrival in Venice he checked into the Hotel Danieli, then, as now, one of the grandest hotels on earth.

For Italians the Great War was fought along the border with Austria, in the mountains to the north and east of Venice. The city was drastically changed. The summer of 1914 had been, according to the contemporary Venetian historian Gino Damerini, an especially brilliant season. American, English, French, German, Hungarian, and Russian visitors packed out the hotels, restaurants and beaches, ‘each competing with the others in luxury, nudist exhibitionism, hedonist wildness, carnivalesque fancies and pretentious elegance’. The palaces along the Grand Canal, many of whose proprietors were d’Annunzio’s old acquaintances, were all open, flooding the hot, still nights with light and music. Then came the assassination at Sarajevo, and ‘at the echo of the first cannon shot all those people … the illuminations, the silk, the jewels, the kaleidoscopic game of devil-may-care sophistication … vanished, as though sucked away by a whirlwind’. By the time d’Annunzio arrived a year later, Venice had assumed the character of a military and naval base, and a city under imminent danger of attack. The larger canals were blocked. The altane, the rickety wooden roof terraces with which the land-starved Venetians have been consoling themselves for their lack of gardens since at least the fifteenth century, had been taken over by air-raid wardens: on the high platforms where Carpaccio painted courtesans bleaching their hair in the sun, there were now searchlights and sirens. Statues were hidden by mounds of sandbags. The palaces and churches stood stripped, their treasures removed and hidden. Hotels were hospitals. The entrance halls of grand houses sheltered refugees. At the brightest of times Venice is a place in which one easily loses oneself. Blacked out, it became a labyrinth through which its inhabitants fumbled at night as though blind.

En route north, d’Annunzio wrote in his notebook: ‘Sense of emptiness and distance. Life and the reasons for living elude me. Between two streams, between past and future … Tedium. Lukewarm water … Necessity for action.’ On arriving in Venice, finding action was, accordingly, d’Annunzio’s first priority. Within two days, he was on board the leading destroyer of a naval squadron on night manoeuvres, travelling east along the coast towards Austrian-held Trieste in the hope of encountering enemy vessels.

He made notes about the moonlight, the crisscrossing lines of the ships’ wakes, the sailors eating as they sat silent around their guns, all of which later found its way into his wartime writings. He was to be a witness: he was also to be an ‘inspiration’. Two weeks before his arrival the Italian cruiser Amalfi had been torpedoed and sunk. Scores of Italian seamen died. D’Annunzio addressed the survivors, who were being sent back into action. ‘Now is not the time for words,’ he said, for the first of many, many times; but words were what he brought them. Throughout the remainder of the war he was to speak again and again, to men going into battle, to men returning exhausted, to men burying their dead. He spoke of blood and sacrifice, of memory and patriotism, and the duty owed by the living to those who had died for Italy. His funeral orations posthumously awarded the wretched conscripts the dignity of heroes; his pre-battle harangues presented the bloody slog of modern warfare as noble sacrifice. His gift for oratory had become an instrument of war.

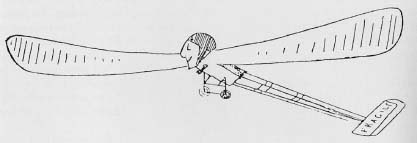

To urge others on, though, was not enough to satisfy him. He sought a role appropriate to a superman. He found it in the air. D’Annunzio had always been fascinated by flight. For decades he worked and reworked the myth of Icarus in his poetry. We have already seen him making his first flight at the 1909 Brescia air show. When he moved to France he frequented the airfield at Villacoublay, and several times he flew again. Shortly after arriving in Venice in July 1915, he made his way to the island airbase at Forte Sant’Andrea, at the mouth of the lagoon. There he met the young pilot, Giuseppe Miraglia.

Well connected (his father was director general of the Banco di Napoli and a political insider) and, according to d’Annunzio, bronze-skinned, with greenish-yellowish eyes flecked with gold, Miraglia was a paragon to his fellow servicemen, known for having gone alone into enemy-occupied Pola with only a pistol for defence. He was to be the first of a series of young men who became for d’Annunzio, during the war years, at once beloved comrades and incarnations of his ideals of youthful valour and fit sacrifice. ‘Blessed are those who are now twenty years old,’ he said. He worshipped and envied their beauty and took enormous pleasure in the opportunities the war afforded him to live alongside them as companions-in-arms. Their deaths were marvellous to him. When they were killed, as one after another they were, he took them into the pantheon he was elaborating in his writing and speeches, making them the martyrs and cult heroes of his new mythology of war.

From Miraglia, d’Annunzio learned that a bombing raid on Trieste had been proposed. Trieste, the cosmopolitan city at the head of the Adriatic, then Austria’s chief port, was one of the irredentists’ most yearned-after lost territories. Here was an exploit exactly to d’Annunzio’s taste. He was an aviator. Venice and Trieste are barely 150 kilometres apart, a short hop for a modern plane, but in 1915 a formidable distance. As a showman d’Annunzio saw how the flight could become a piece of splendidly theatrical propaganda. He determined to claim it for himself. He and Miraglia would drop explosives on the Austrian emplacements in the harbour but – more importantly as far as d’Annunzio was concerned – they would also drop pamphlets (written, of course, by himself) over the town’s main squares.

With Miraglia he began to talk of ways and means. He studied maps of the coastline they would overfly. He thought about the best design for the little sandbags to which the leaflets would be attached, and went himself to the Rialto market to buy the necessary canvas. He reflected happily that, thanks to his rigorous programme of exercise followed over many years, he was more than fit enough for the physical ordeal of the flight and confident of being able to hurl bombs or sandbags from the unstable perch of a tiny plane. He drafted a message to ‘the Italians of Trieste’, assuring them of his devotion to the cause of their imminent liberation, and copied it out over and over again in his own hand, taking care that his signature (often an exquisite but illegible arabesque) should be unmistakably clear.

Word got out, and reached a reporter. Anything d’Annunzio did was not only a gossip column item, but a news story. A Venetian journal announced the projected flight, and that the poet was to join it. The admiral commanding the tiny air force was doubly dismayed, firstly by the breach of security – clearly it was going to be hard to keep any operation in which d’Annunzio was involved secret from the enemy – secondly, by the risk of this inconveniently famous subordinate getting himself killed. D’Annunzio alive could help to encourage the troops and, if he continued to produce the kind of furiously nationalist poetry that he had been writing over the previous decade, help maintain the civilian population’s support for the war. His death, on the other hand, would have a deleterious effect on the entire nation’s morale.

The admiral vetoed the flight. D’Annunzio protested. The admiral consulted his superiors. Telegrams went back and forth between Rome and Venice and the military headquarters near the front at Udine. None of the authorities wanted to sanction the flight. The order came down: d’Annunzio’s life was ‘preciosissimo’ and must be conserved. He was forbidden to join this or any other dangerous operation. Furious, d’Annunzio went to the top. On 29 July he wrote an impassioned letter to Prime Minister Salandra.

He flattered: ‘You, whose own spirit is so hard-working and so generous, must understand me.’ He stressed his physical competence. He was not ‘a man of letters of the old type, in skull cap and slippers’. He was an adventurer. ‘My whole life has been a risky game.’ He boasted of his past daring. ‘I have exposed myself to danger a thousand times against the fences and hedges of the Roman Campagna’ (he adored fox-hunting). In France he had often been out on the Atlantic in chancy weather ‘as the fishermen of the Landes could tell you’. He had ventured repeatedly into enemy territory on the Western Front (he visited the front twice, staying on the safer side of the French lines). Most importantly, ‘I am an aviator … I have flown many times at high altitude.’ (This wasn’t strictly true either.) And he wasn’t only brave: he had knowledge and skills which could be useful. He knew Istria, he knew Trieste. He had an ‘observant spirit’.

Having presented his credentials, he made his request, in the most insistent terms. ‘I pray, I beg … repeal this odious veto.’ He hinted that if he were not allowed to risk his life in his own way he would deliberately endanger it by going straight to the front. To bar one with ‘my past, my future’ from living the heroic life would be ‘to cripple me, to mutilate me, to reduce me to nothing’. The troops, the press, the people of Italy all saw him as ‘the poet of the war’ – now the authorities were trying to treat him as an exhibit in a museum.

Minister Martini scoffed at the suggestion that fox-hunting and jaunts in pleasure boats provided the necessary experience for the kind of role d’Annunzio was claiming. But Salandra was impressed by d’Annunzio’s earnest tone. The ban was lifted. The flight would go ahead.

Exultant, d’Annunzio went shopping again. At the haberdashers he chose ribbons (red, white and green, the colours of the Italian flag) with which to adorn his missives to the people of Trieste. He filched a sandbag from among those banked up along the façade of St Mark’s. Its contents, sanctified by contact with the ancient building, the hub of the Venetian Empire, would give his little packets historical gravity as well as physical weight. He bought himself thick woollen vests and long johns and when all was ready, all the little bags stowed away in one big one, he danced ‘a pyrrhic dance of joy around them’.

The date of the enterprise was fixed for 7 August, which d’Annunzio considered an auspicious date. He prepared himself – as was only realistic in those early days of flying – for death. He would write a few months later about the mornings on which he set out for such missions, ‘the thought of returning was left in the vestibule, despised, as a vile encumbrance’, and recall how he sat once with a pilot before a flight, talking easily about routes and equipment, but aware that ‘each of us, by noon, could be a fistful of charred flesh, a crushed skull with gold teeth glinting in the mess’. He drew up a will, and entrusted it to Albertini.

On 6 August he and Miraglia made a test flight. D’Annunzio had flown before, but only rising briefly over airfields. Now he looked down on a great city, seeing Venice as only a handful of human beings had ever yet seen it. He was the first writer to record the experience. He wore, as all the aviators did, heavy leather gloves. When he took one off to help Miraglia tighten the elastic of his chinstrap he at once felt his fingers begin to freeze. All the same, belted into the forward seat, exposed to every wind in the shaky little flying machine, he persistently scribbled down his impressions. The diverging lines of a ship’s wake were like ‘the palms in the hand of Victory’. Venice’s islands, divided up by canals, resembled the segments of a loaf of bread. The long railway bridge was the stem to the city’s flower. The wind-ruffled water by the lagoon’s outlet was iridescent as a pigeon’s throat. The mainland – in August’s dryness – was blonde, feminine, girdled by the pale ribbons of dykes. Avidly absorbing these new sights, fixing them with similes, d’Annunzio makes no mention of discomfort, or vertigo or fear.

On the morning of the seventh he performed his usual toilette – a vigorous massage administered by his servant followed by a bath – and thought about the possibility that the body he was tending might, by nightfall, be stripped and laid out dead. After breakfast (strong coffee) he went shopping again, for another woollen jumper: he must have felt the cold the day before. Walking back towards the Hotel Danieli he encountered the Countess Morosini, with her daughter, the Countess di Robilant. It is one of the oddities of d’Annunzio’s war experience that on his way into action of the most serious kind he might find himself chatting with an acquaintance about a social engagement. Annina Morosini, known to the gossip columns as the ‘uncrowned Queen of Venice’, was the chatelaine of the Palazzo da Mula on the Grand Canal and a generous friend to the poet. That morning he noticed how lovely her eyes were, and jotted in his notebook ‘still desirable’ (she was fifty-one). He told her what he was about to do and asked her playfully to give him a talisman. She demurred, offering him only her blessing, but saying she would telephone that evening. He was offhand about the latter promise. ‘I don’t know what she’s calling for,’ he noted. Given his thoughts at bathtime, the coming evening must have seemed remote. Back in his hotel room he filled a cigarette case with cartridges, laid out his woollen flying gear and wondered: ‘Will it be cold up there, or down there?’ (The underlining is his.) He was thinking of the sea bed. Remembering that he might not die but be taken prisoner, he put six of the laxative tablets he swore by, and some cash, in his pocket, then went down and took the waiting gondola to the airfield. Miraglia was ready for him. They set off on the flight which would take them further than any Italian pilot had flown before, and well within range of enemy guns.

In the notebook d’Annunzio was carrying that day, his poet’s-eye observations – ‘the teeth of the breakwaters which gnaw at the unhappy sea’ – are interspersed with dialogue. The two men couldn’t speak to each other. The only complaint d’Annunzio makes about the physical circumstances of the flight are about the engine’s atrocious din: he regrets not having brought wax earplugs. He and Miraglia communicate by passing book and pen back and forth, d’Annunzio having to twist awkwardly in order to do so. Their initial exchanges are pleasantly companionable: ‘Are we still climbing?’. ‘You look like a bronze bonze [a Japanese Buddhist monk]’, says d’Annunzio to Miraglia. ‘Do you want some coffee? It’s really hot.’ Soon though, more urgent messages are passing between them. D’Annunzio was not just there to make notes on the landscape (‘in the pallor of the lagoon the twisting canals are green as malachite’), he was also the bombardier.