Полная версия

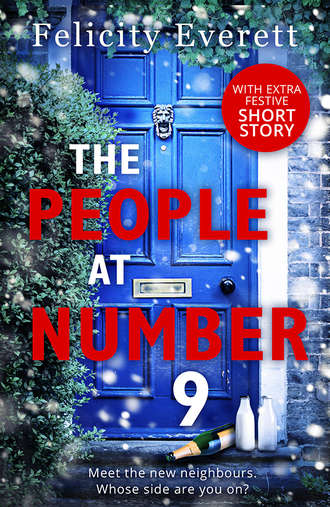

The People at Number 9: a gripping novel of jealousy and betrayal among friends

“Which you almost never are…”

“I’m actually under the cosh quite a bit since I upped my hours,” said Sara, irritated by Carol’s sly dig. “She’s saved my bacon a few times.”

Carol twisted her mouth into an approximation of a smile and for a second Sara felt like Judas. Hadn’t Carol also saved her bacon over the years? The time Caleb was rushed to A&E with suspected meningitis? The day the guinea pig disappeared?

“Anyway, if you do want to come,” her friend was saying now, as she handed the leaflet to Sara, “can you let me know ASAP?”

Sara took this as a veiled reference to the last time they had gone to the theatre, when Sara’s prevarication had meant the only available tickets had been for the surtitled performance for the hard of hearing. Sara smiled, closed the front door after Carol, and put the leaflet straight in the recycling.

She was sorry they were drifting apart, but sometimes you just outgrew people. Friends like Lou and Gavin didn’t come along every day, and she felt such warmth towards them, such gratitude that they had come into her life and made it three-dimensional and vivid. She felt she had been sleepwalking until now, lulled by the conformity, the complacency of everyone around her. How could she go to Carol’s book group and discuss the latest Costa prize fodder now that Lou had introduced her to the magic realists of Latin America whose profound ideas wrapped up in hilarious flights of fantasy were like fairy tales for grown-ups? There was no doubt about it, Sara was learning a lot. It wasn’t a one-way street, though. Sometimes she surprised herself with her own perceptiveness. She had recently aired her pet theory that Georgia O’Keefe’s famously Freudian flower paintings were perhaps just flowers and not, as the art fraternity would have it, symbolic vaginas, only for Lou to confirm that this was, in fact, what the artist herself had always claimed.

The most rewarding aspect of their friendship, though, wasn’t the head stuff, but the heart stuff. After a surprisingly short time, Sara had found herself confessing things to Lou that she had never said to anyone else, not even Neil. Lou had set the tone that first afternoon, when she had cried about the trout farm, but since then, whether surrounded by childish clamour at teatime or listening to Dory Previn beside the dying embers of a late-night fire, they had shared some of the most intimate aspects of their lives. Sara didn’t even mean to say half of it – it just came tumbling out, her unhappy teenage promiscuity; her botched episiotomy and its impact on her and Neil’s sex life; her disappointing career and suspicion that Neil was secretly happy about it because he wanted a traditional wife. Lou was such a good listener. She had a way of asking just the right question, or upping the ante with a heartfelt confession of her own. She managed to make Sara feel both entirely normal in her anxieties and utterly exceptional in her talents. “But you’re so gorgeous, I can’t believe you had to shag a bunch of spotty oiks to prove it,” she would say, or “Creativity just oozes from you, Sara; the way you live, the way you raise your kids – I don’t think you realise how inspiring that is to someone like me.”

It was true that Lou had her shortcomings, but this only made her more interesting. Sara had heard her lose it with the children on a number of occasions. She blatantly favoured Dash over Arlo in a way that made Sara wince for the younger boy. Then there was the rather complex matter of Lou’s relationship with Gavin. There was a neediness in the way Lou related to her husband that didn’t seem quite healthy to Sara. Surely one shouldn’t be competing with one’s own children for the attention of their father? Yet Sara saw this happen often. Once, she had been in the kitchen chatting amiably with Gavin while she waited for Lou to get ready. The two women were going to see a film together, though if Lou didn’t get a move on they’d miss the beginning. Gav had been dandling little Zuley on his lap and marching toy farm animals across the table, interspersing adult conversation with a variety of silly moos and grunts that were making the three of them giggle. They were so absorbed that it was a moment or two before they noticed Lou had joined them. Wreathed in perfume and got up like an art-school vamp, she began clattering cupboard doors noisily in what looked, to Sara, like a flagrant bid for attention. And did Zuley, at nearly three years old, really need a bottle of milk thrust into her mouth, mid ‘‘Baaaa,” just so that Lou could pirouette girlishly in front of Gavin and solicit his opinion on her outfit?

Yet Sara wasn’t quite sure she was being objective. The air around Gav and Lou fairly crackled with sexual static and it made Sara envious. If the roles were reversed, would she care what Neil thought of the way she looked? If he were absorbed in a game with the boys – well, first of all she’d pinch herself to make sure she wasn’t seeing things, and then she’d leave while the going was good. No pirouetting, no eyelid-batting. All that was in the past. They’d been married fifteen years, for goodness’ sake. Surely, a certain amount of complacency was natural, desirable even?

Then again… ever since she’d witnessed it, she’d been unable to get that tango out of her mind. It had made her wonder whether all her life she had been doing sex wrong or, worse, with the wrong person. She watched, now, as Lou leaned in to kiss Gavin languidly on the lips. Zuley, eyes rolling with pleasure as she slugged back the milk, reached up a plump fist to grasp her mother’s forearm, but Lou prised the child’s fingers away and gave them a cheerful shake of admonishment.

“Mummy’s got to run,” she said, glancing at the sunburst clock on the kitchen wall. “You’re making Mummy late.”

They arrived five minutes into the film, just as the opening credits were starting. It was a gritty, low-budget number, which had got four stars in the Guardian. Sara took a little while to acclimatise, but half an hour in, she was starting to enjoy it; Lou, on the other hand, seemed to be growing restless. She kept shaking her head and laughing under her breath at things Sara didn’t think were meant to be funny. Finally, after what seemed to Sara a rather moving scene, Lou groaned loudly and rested her head on Sara’s shoulder.

“Do you want to leave?” Sara whispered anxiously. She couldn’t have been more mortified by Lou’s reaction if she had made the film herself. Lou nodded and, muttering apologies, they climbed over the laps of their fellow audience members before escaping to the bar.

“I had a feeling it’d be like that,” said Lou (Like what? wondered Sara). “I nearly said something when you suggested it, but I thought, give the guy a break.”

“Do you know the director?”

“He was in the year above me at St Martins. Very talented. Always wanted his name up in lights and now he’s got it. Just a shame he had to compromise the integrity of the film.”

“Compromise how?”

“Oh everything. The aesthetic, the soundtrack, the casting,” said Lou. “That grainy, cine-film thing? I mean, sorry, but yawn.”

“Mmmm,” said Sara.

“And the lead actor? Totally unbelievable in the role. Straight out of RADA, but, you know, he’s up and coming. Getting him’s a coup, so…”

“Right,” Sara nodded, thoughtfully. “Who would you have cast?”

“Oh an unknown,” said Lou. “I’d never compromise the integrity of the film for a ‘name’ actor. It’s just not worth it.”

Sara took a sip of her drink and tried to appear nonchalant. “So, I’ve been dying to ask: what’s your new thing about?”

“What’s it about?” Lou frowned humorously, and Sara blushed. “Well, it hasn’t got a plot as such. It’s not that kind of film. But I suppose, if I had to sum it up… it’s a sort of urban fairy tale.”

Sara nodded. “And it’s a short?”

“Yes. But a short film has to work that much harder to earn its keep. No indulgences. No flights of fancy. Every frame counts. And because shorts aren’t really made for a mainstream audience, there’s a… I won’t say higher... a different expectation on them to deliver.”

Sara nodded again.

“So, forgive my ignorance, but who actually watches them?”

“Well, there are all these amazing festivals now…”

“Sundance?”

“Sundance is a bit old hat, but there are lots of other really interesting ones all over the world: San Sebastian, Austin, Prague. You just hope to premiere your film at one of them and get good notices…”

“So that’s who they’re for, the critics?”

“Well, no,” Lou said, “they’re for everyone.”

“But they don’t go on general release?”

“Well, you’re not really looking for bums on seats…”

“What are you looking for?”

“Well an audience…”

“But not a big audience.”

“A discerning audience.”

“Ah…”

“And enough money to make your next film. Making the things is a doddle compared to financing them. I sometimes wish I’d studied accountancy…”

“Lou…”

“Yes?”

“I was wondering…”

“What?”

“Oh, no, you’re busy…”

“Come on, out with it. Gav said you’d got some writing on the go. You want me to have a look?”

Sara smiled hopefully. “I would love to know what you think.”

“It’d be an absolute privilege.”

“You might hate it. If you hate it, you’ve got to promise you’ll say so…”

“How could I hate it? I would tell you, though, of course I would. Not to would be a betrayal of our friendship, but I can’t imagine someone as clever and sensitive, and off-beat as you, could possibly write anything bad.”

Sara glowed with pleasure. Was she off-beat? She certainly hoped so.

***

It turned into another late night. They were pretty well-oiled when they tumbled out of the taxi and Lou eagerly accepted Sara’s invitation of a nightcap. Neil must have only just gone to bed, because the wood burner required only a little stoking to send flames licking up the chimney again. Sara put Nick Drake on the stereo, broke out the Calvados and the conversation turned, once again, to matters of the heart. Sara found herself reminiscing, dewy-eyed, about Philip Baines-Cass, the boy who’d played opposite her in a fourth form production of Hobson’s Choice.

“He wasn’t really good-looking,” she remembered fondly, “but he had this incredible charisma. He was the kind of person you couldn’t not look at. He was clever but cool and you didn’t really get that combination at my school. I’m kind of surprised he didn’t go into acting actually – he seemed like he was made for it.”

“Probably a computer programmer in Slough,” Lou chuckled. “Go on…”

“Well, so he was this… amazingly gifted actor and I was this stilted little am-dram wannabe, and there was this one scene where we had to kiss, and I would be literally shaking as it got nearer. On the one hand, I was dreading it, because every time we did it in rehearsal, everyone whistled and slow-handclapped and stuff; but on the other hand…”

“…You couldn’t wait.”

“Exactly. So, anyway, it comes to the big night and the play’s going really, really well. You can sense the audience is on our side. Even the rubbish people aren’t fluffing their lines and our big scene’s coming up and I’m just crapping myself. But then it’s like someone flicks a switch and I think, ‘Fuck it’. I just go for it. You could have heard a pin drop. It was amazing.”

Lou grinned. “How long did you go out with him for?”

“Oh, we didn’t go out,” Sara replied, “he had a girlfriend.”

“But you got a shag at least?”

Sara shook her head.

“He wanted to. At the after-show party, but I was a virgin.”

“I thought you said…”

“That was afterwards. I overcompensated,” Sara laughed, but she found herself welling up. “He was really mean. Called me a frigid little prick-tease and got off with Beverly Wearing right in front of me.”

“What a cock!”

“I know. But the funny thing is, even though he was a total cock, I’ve always wondered what it would have been like. It’s kind of haunted me, because I never really enjoyed it with any of the others. I think I was just trying to show him that I wasn’t… what he said.”

“Well, at least you did – show him, that is.”

“I don’t think he even noticed, to be honest. I was never girlfriend material for someone like him. I only came on his radar because of the play, and the one chance I had with him, I blew. I still think about that kiss…”

It was true, she did still think about it; more and more lately. The trouble was that the harder she tried to recall the facial features of Philip Baines-Cass, the more they tended to meld into Gavin’s.

There was a pause while Lou tipped herself out of the armchair, drained the last of the Calvados into their glasses, and shuffled backwards on the hearthrug until her back met the sofa.

“Funny, isn’t it?” she said, taking a thoughtful sip. “How different it all could have been, I mean same for me. God, I shudder to think of it! I was almost with that computer programmer from Slough.”

“You!”

“I know! Imagine. He wasn’t actually a computer programmer, obviously; nothing quite that bad.” They chuckled. “His name was Andy. He was a very sweet guy, and he’s loaded now. My Mum never misses a chance to slip that into the conversation: ‘I saw Andy Hiddleston at the weekend, Louise. Did I mention he’s a property developer?’” She rolled her eyes. “She’s never quite forgiven me for breaking off the engagement.”

“You got engaged?”

Lou nodded, delighted with the incongruity of it all.

“Until I went for my interview at St Martins and realised the world had other plans for me.”

“Poor Andy!” Sara sniggered.

“I know,” agreed Lou, “he didn’t take it very well,” she shook her head and grinned fondly, “then again; I’d only have made him miserable. Can you imagine? Me in a double-fronted, Bath-stone villa with a monkey-puzzle tree and a waxed jacket…”

“… Two-point-four children…”

“… A Range Rover…”

“… And a lobotomy!”

Sara started giggling and found she couldn’t stop. She forced the back of her hand to her mouth in an effort to control it.

“Come along, Camilla, we’ll be late for pony club!” said Lou in a plummy accent.

“Now then, Nicholas, don’t cry,” joined in Sara. “All big boys hef to go to boarding school.” Lou beat the hearthrug in merriment. Tears ran down Sara’s face.

“Introducing… the new… Chairwoman of the… Townswomen’s Guild,” Sara tried to say, but it came out as a series of gulps and squeaks.“Mrs Andy Hiddle…” she gasped, then keeled over on the rug, insensible with mirth.

6

It was hard to concentrate the next day, partly because of the hangover, but mainly because, somewhere along the line, Sara had lost even the small shred of enthusiasm she’d once had for her job. She found herself reading and re-reading the same phrase – “I don’t really have a preferred supermarket and tend to use whichever is most convenient” – until the words merged into one another and ceased to hold any objective meaning. For a stopgap job, NPR Marketing had taken up an awful lot of her time. Other creative types who had joined when she did had long since moved on. Anders the miserable Swede now wrote voice-overs for Masterchef; Tracy Jackson was a lobbyist for the Green Party. But NPR had granted Sara two generous periods of maternity leave and, although her game plan had been to return after Patrick’s birth for no longer than her contract dictated, five years had somehow elapsed and she was still sitting at the same desk, in what was essentially a cupboard, opposite the talented but cynical Adrian Sutcliffe.

A part of Sara had known for a long time that her and Adrian’s relationship was unhealthy. They were co-dependants, facilitating each other’s inertia through corrosive humour. As long as they channelled their creative energies into satirising the futile nature of their work, the slavish ambition of their less talented colleagues and the passive-aggressive behaviour of their workaholic boss, Fran Ryan, they could kid themselves that they were, respectively, a novelist and a journalist manqué.

“Eyes front,” said Adrian now, “Rosa Klebb at three o’clock.”

Sara snapped out of her reverie and battered her computer keyboard with a flurry of random keystrokes.

“On my way to Gino’s,” said Fran, “can I get you anything?”

“Ooh lovely,” said Sara, “tuna melt for me, hold the mayo.”

“Why do you let her do that?” said Adrian, after Fran had gone.

“Er… because it’s lunchtime and I need something to eat,” said Sara, with the interrogative upward lilt she had picked up from her children.

“You know what she’s up to, don’t you?”

“She’s getting my lunch?”

“Yeah, so you don’t leave the building.”

Before Sara could make a suitably acerbic retort, Fran had popped her head back into the office.

“By the way, can I tell Hardeep that you’ll ping the survey across by close of play today?”

“Yep. On it,” Sara said, picking up her biro as she spoke, ready to throw it at Adrian as soon as the door had closed.

Lately, Sara’s boredom was making her rebellious. Neil’s promotion was practically in the bag, and he had hinted on numerous occasions recently that she might at last like to “free herself up” from the rigours of work, which she took to mean free him up from the necessity to dash round Waitrose after a hard day at the office. She had resented the suggestion at first, but since Lou had been so encouraging of her writing, she was beginning to harbour serious ambitions in that direction. When Fran returned with her sandwich at one thirty, she didn’t bother to minimise her computer screen; instead, she doubled the font size.

As the front door banged shut behind Nora’s father, the draught wafted an empty plastic bag up in the air. Nora watched it as it rose and seemed to inflate itself with his very absence, before floating back down and lodging between the banister rails. She started to sing quietly,

“Bye baby bunting, daddy’s gone a-hunting, she sang, over and over, until the words became, not words, but sobs.

“One tuna melt,” said Fran, barely able to tear her eyes from the screen. Sara scrabbled in her purse and handed Fran a fiver, which she took, without shifting her gaze.

“It’s okay, I don’t need any change,” said Sara, pointedly.

“No, right,” said Fran, remembering herself. “Er… well, bon appétit,” she added, giving Sara a terse little smile before she left the room.

“The worm turns!” said Adrian, with grudging respect. Sara nodded in haughty acknowledgement and took a greedy bite of her sandwich. A large gobbet of mayonnaise dripped onto her jumper.

On the train home, she spotted Carol’s Simon getting on further down the carriage. Normally she’d have lowered her eyes to her Kindle, certain in the knowledge that everything they had to say to one another could be covered on the short walk between the station and their road, but she had hatched a plan and was bursting to tell someone, so she called out his name.

“Oh, hello, Sara.” He started to thread his way through the carriage towards her. She could tell from the look of portentousness on his face that he had some news of his own to impart. “I expect you’ve heard…” Sara prepared herself for the death of a pet, or a recurrence of Carol’s sister’s ME.

“What?”

“Cranmer Road got a stinking OFSTED report. One step away from special measures.”

“Shit!” Sara remembered her words to Gavin, as he’d urged a reluctant Arlo over the threshold on the first day of term: “Don’t worry, it’s a really lovely school. You won’t regret it.”

“Carol must be doing her nut.”

“Oh, I think she’s secretly quite pleased,” said Simon, “she’s been looking for an excuse to go private for ages.”

Sara stretched her lips into a smile.

“It was the numeracy that did it, apparently,” Simon added, “that and inadequate special needs provision.”

“Inadequate special needs? That’s a travesty,” spluttered Sara. “They bend over backwards at that school…”

Simon raised a didactic finger. “Ah but special needs includes GAT, you see.”

“GAT,” repeated Sara dumbly.

“Gifted and Talented,” said Simon, patiently.

Of course. The middle classes were in revolt because they thought the Head was squandering resources on the thickies instead of hot-housing their little geniuses.

“Ridiculous,” she said.

“Well, I’m not so sure…” Simon demurred. Then, sensing an ideological rift opening up, asked quickly, “How’s work?”

“Oh, you know, alright.”

Suddenly, Simon was the last person with whom she wanted to share her burgeoning literary ambitions. She could just imagine the smirk on his face as he relayed the news to Carol that she’d given up work to write a novel.

She expected better of Neil though.

“I’m not saying, don’t do it,” he said defensively over dinner, “I’m just querying the timing, is all.”

Sara tried not to wince at the Americanism. They seemed to be creeping into his vocabulary lately. She wasn’t sure if he had picked them up from watching back-to-back episodes of Breaking Bad, or from reading American business manuals, but, either way, they didn’t enhance his credibility as a literary adviser. He seemed to think she should do a course. As if creative writing was something that could be taught, like car maintenance or Spanish. And yet, the most irritating part of this suburban inclination of his to kowtow to “teachers”, was the fact that it piqued her own insecurity. She didn’t want some second-rate novelist picking over her work. She much preferred Lou’s bold exhortations to “just go with it”, to “trust the muse” and “tap into whatever’s down there.”

Now she found herself becoming tearful with frustration. She planted her fork in what remained of her quiche and tried not to let her voice quaver.

“I don’t think you realise what it’s like for me,” she said. “I’d like to see you spend eight hours a day writing consumer questionnaires.”

Neil looked up in dismay and Sara realised, with a mixture of satisfaction and shame, that the tears had clinched it for her, as they always did with Neil.

“No,” he said, apparently overcome with contrition, “you’re better than that. I totally agree. Go for it then. You’ll have six whole hours a day while they’re at school.”

Sara was about to point out that creativity wasn’t necessarily something you could turn on and off like a tap, but thought better of it.

“It certainly won’t hurt to be around more,” she said, “especially with the school on the slide.”

“What do you mean?” said Neil.

“They’ve had the thumbs-down from the inspectors,” said Sara, rolling her eyes, “so expect a mass exodus. Carol’s already looked at St Aidan’s, apparently.”

“We don’t have to copy Carol.”

“It’s not Carol I’m worried about,” said Sara, “it’s her influence on the others.”

“Carol is a bad influence on the other parents,” Neil affected a pedagogic tone.

“I wish you’d take this seriously. Carol wraps Celia round her little finger.”

“And I should care because…?”

“Celia’s Rhys’s mum, and Rhys is Caleb’s best friend.”

“I think you’re making a meal of it. Boys aren’t like girls. It’s easy come, easy go.”

But the damage was done. Sara could only look at Cranmer Road with a jaundiced eye now. As she and Lou sat in the school hall, the following week, waiting for the Harvest Festival to begin, her eyes roved critically around the display boards. BE KIND TO OTHER’S read one poster, its misplaced apostrophe less worrying than the conspicuous indifference of the Year Ones to its message. When the piano struck up the opening song, and the children joined in with their warbling falsettos, Lou dabbed a sentimental tear from her eye, but Sara felt like crying for a different reason. The “orchestra” consisted of three recorders and a tambourine; the harvest gifts, displayed on a tatty piece of blue sugar paper, were mostly dented cans of Heinz soups and dubious-looking biscuits from Lidl. This spoke eloquently to Sara of the disengagement of the middle-class parents. The only item of fresh produce was the pineapple she had donated herself. Most distressing of all was the palpable unease among the staff. Gone, were the wide smiles and big encouraging eyes. Gone was the sense of camaraderie and fun. To a man and woman, they wore the weary, defeated expressions of an army in retreat.