Полная версия

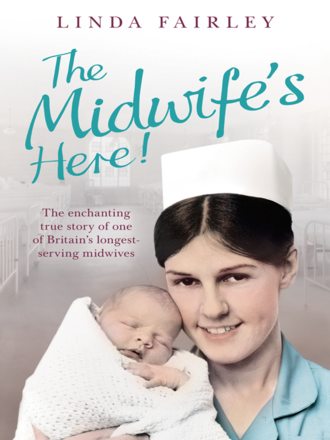

The Midwife’s Here!: The Enchanting True Story of One of Britain’s Longest Serving Midwives

Sister Craddock led a small group of us down several corridors and towards one of the urology wards, continuing to lecture us about hygiene.

‘What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger,’ she said, and I wondered what she could mean by that. Were the cleaning fluids dangerous? What could possibly threaten us here in the hospital? I was getting used to her loud, melodic voice now and my mind was wandering.

As we approached the ward a sudden, silly image flashed into my head. I imagined Sister Craddock stepping up on stage and belting out the song ‘Goldfinger’. Shirley Bassey was Welsh, wasn’t she? Sister Craddock didn’t look anything like Shirley Bassey but she certainly sounded like her. I could just picture her singing her heart out, flinging her arms wide at her grand finale, then afterwards pointing at the audience triumphantly and declaring: ‘What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger, ladies and gentlemen …’

‘Cleanliness is of the utmost importance on the wards, and to maintain our high standards is essential.’ Sister Craddock’s stern words hauled me back into the moment. Images of sequins and stage lights were extinguished in a flash, replaced by thoughts of dusting cloths, mops, buckets and disinfectant. I listened earnestly.

‘We have Nightingale wards here, girls, and if she were alive I would want Florence Nightingale herself to be proud of the cleanliness of them.’

I knew the large, open-plan wards were named after Florence Nightingale because she pioneered their design, but if I’m perfectly honest that was as much as I knew about them, despite their famous namesake. I was curious to find out more.

Sister Craddock pushed her soft bulk through a set of double swing doors, giving us our first glimpse of ‘her’ ward. The smell of cleaning fluid made my nostrils tingle as I stepped into this new territory. ‘Follow me, girls,’ she instructed. ‘I will give you a brief tour of the ward. Please be respectful of patients. No talking. I will do the talking.’

We stood in the first section of the ward, which Sister Craddock explained had a kitchen and a double side room to the left, and sister’s office, linen cupboards and two single side rooms to the right, which we were not invited to enter. Before us stood another set of swing doors, which led into the main part of the ward. We filed gingerly through, eyes and ears wide open.

Twelve beds lined each side of the vast ward, all occupied by ladies in varying stages of sleep who were swathed in flannelette nightgowns and knitted bed jackets. Most looked cosily middle-aged and some wore hairnets and sucked their gums as they surveyed us curiously but courteously.

There was something slightly surreal about the scene that I couldn’t quite put my finger on. One or two women were a bit younger and more fashionable than the others, with floral-print nightgowns and bobbed hair, yet there was an unmistakable correlation between them all.

Down the middle of the ward stood the night sister’s table, covered in green baize and with a large lamp hanging above it. At night, we were informed, a green cloth was placed over the lamp to create an air of calm and promote restful sleep. Beyond it, but also in the centre section of the ward, was a store cupboard plus a metal trolley housing a sterilising unit, and finally the patient’s long wooden dining table.

A sluice room, toilets and a bathroom were situated in the far right-hand corner of the ward, behind bed thirteen. Under the windows at the very back of the ward there was a small television, a few Draylon-covered armchairs and a low coffee table with a neat pile of women’s magazines on it. There was also a round, black ashtray, which had a cover. I’d seen one like it before and knew that when you pressed the button on top the ash would spin cleanly out of sight.

Sister Craddock’s voice sang on as I took in the scene. ‘There are twenty-eight beds in all; four in the side rooms and twenty-four in the main ward. Each ward is run by one sister, six to eight staff nurses and between ten and sixteen student nurses working around the clock. Shifts run from 7 a.m. to 5 p.m., 1.30 p.m. to 9 p.m. and 9 p.m. to 7.30 a.m. Jobs are allocated at each shift change and routines must be strictly adhered to.’

As Sister Craddock spoke, a penny slowly dropped for me. I looked at the twelve beds lined up along each white-painted wall and realised how perfectly arranged they were.

‘The ward has to be clean, neat and tidy at all times,’ the Welsh voice continued. ‘Patients are washed and have their beds changed every day. Bedding must be fitted exactly the same way each day, with enveloped corners on bottom sheets, pillowcase ends facing away from the doors and perfectly folded counterpanes on top of the blankets. You will receive precise instruction in bed-making procedures in due course. Please remember always to pull the top sheet up a little to make room for the toes, and to leave the counterpanes hanging at the sides, for neatness. The wheels of the bed must all point in the same direction, and nothing is to be left lying around on the tops of the lockers.’

That was it. The immaculate presentation of the beds and furniture was what made the ward appear slightly surreal. I had never seen such a well-ordered room in my life before, and I marvelled at how a ward full of sick women in a mishmash of nighties and hair nets could look so methodically well ordered.

The crisp cotton counterpanes were all pale green to match the curtains that could be pulled around each bed. Every bedside locker had a little white bag taped to it for rubbish, leaving the top clear for a jug of fresh drinking water and a glass. Some patients had a vase of flowers on their locker-top or one or two get well cards.

‘Only one bunch of flowers is permitted per patient,’ Sister Craddock cautioned, ‘and it must be removed to the bathroom at night.’

We nodded in unison. Rudimentary biology told me this had something to do with plants releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere at night.

‘Smoking is permitted on the ward but not encouraged.’ We nodded in agreement again. This seemed perfectly reasonable.

‘Orderlies damp dust every surface in the ward daily: windowsills, lockers, bed frames and furniture. Domestics clean the floors, toilets, bathroom, kitchen and sister’s office, and twice a week they pull out the beds and clean behind them, thoroughly.

‘As a student nurse you will be expected to attend to the general good hygiene of the patients and help maintain the high standards of cleanliness required on the wards. It has been said that you could eat your dinner off the floor of my ward, and that is how it must always be. Please always ensure that even the wheels of the bed are gleaming and, of course, neatly aligned after cleaning. If ever you find yourself with a spare moment, use it to pick up a cloth and damp dust. There is always a surface to be dusted and cleaned, and there is no room here at the MRI for nurses who are slothful or slipshod.’

I watched a sympathetic-looking nurse plump up an elderly patient’s pillow and fill her glass with fresh water. The patient smiled at the nurse as if she was an angel, and the nurse smiled back, explaining courteously that it was time for the patient’s daily injection. The nurse must have been a third year, as she had three stripes of white bias binding on the sleeve of her uniform.

I looked at her in awe and admiration, noting that her bedside manner was as impeccable as her uniform. I wanted to make patients feel better too. I wanted to give them their medicine along with a warm smile. I wanted to be just like that nurse.

A few days later I went to the uniform store with Linda and Nessa, where we were each handed a hessian laundry sack with our names printed neatly across the top in black marker pen. Inside we found our brand new uniforms: three light green dresses made of a sturdy cotton which felt stiff, like new denim, plus ten aprons, three detachable collars and cuffs and a rectangle of white cotton. Sister Craddock deftly demonstrated how to craft the cotton into a perfect cap.

The three of us exchanged knowing glances as we signed for our uniforms and acknowledged the rigid rules about laundering them. This was the moment we’d been looking forward to above all else.

‘I can’t wait to try this on,’ Nessa whispered shyly to me.

‘Me too,’ I said. ‘I hate walking around the hospital in mufti.’

Linda chuckled. ‘Hark at you!’ she teased. ‘A week ago you didn’t even know what the word meant!’

My cheeks reddened. It was true. I’d had no idea nurses used the term ‘mufti’ when referring to their ‘civvies’ or ordinary clothes, but I’d heard it so many times since our arrival that it had slipped into my vocabulary without me even realising.

‘We’re going to be proper nurses now,’ I grinned, picking up my prized laundry bag. ‘We have to use the correct language!’

We carried our uniforms back to the nurses’ home with some ceremony, and all agreed to meet in my room for a ‘fashion parade’ before tea.

My mum had taken me on a shopping trip to Manchester a few weeks earlier and bought me two pairs of comfortable brown lace-up brogues in Freeman Hardy Willis. We had tea and scones with jam and cream in Kendals department store before visiting its grand lingerie section, where she bought me two suspender belts with metal clasps and seven pairs of brown, 30-denier Pretty Polly seamed stockings.

Now I took the underwear out of its tissue wrappers for the first time, and set about clipping, buttoning and lacing myself into my complete nurse’s uniform. I was beside myself with excitement as I pulled on my dress and attached its crisp white cuffs and collar, which had to be buttoned onto the dress. Next I used half a dozen brand new kirby grips to pin my neatly folded cap on top of my hair, which I had scraped back off my face and fixed in a tight bun using several brown elastic bands.

Finally, I placed my stiff white apron over my dress. It was huge! The lower part amply covered my wide skirt, which reached almost halfway down my calves, and the two enormous front flaps that pulled up and over each shoulder came so high they covered half of my neck. The wide straps had to cross over my shoulderblades before being brought back round and attached with a thick safety pin in front of my waist. What a procedure!

I turned and faced myself in the vanity mirror above my washbasin. It was a moment I’ll never forget. I thought of Sue’s sister Wendy, whose uniform I’d always coveted. I thought of all the nurses I’d been impressed by at the hospital. I pictured them soothing brows, pushing trolleys, calming anxious relatives and offering tea in pale green cups and saucers that matched their dresses. Now, in this moment, I saw myself amongst their ranks. ‘I really am becoming an MRI nurse!’ I said to my surprised reflection.

When Nessa and Linda arrived a few minutes later we all shrieked and hugged each other.

‘Will you look at the state of us!’ Linda exclaimed as we ‘oohed’ and ‘aahed’ over each other like bridesmaids before a wedding.

Nessa and I both knew she was feeling exactly the same as us, though: pleased as punch and bubbling with pride.

Sharing such exciting new experiences with the other girls helped me through the first few weeks, although I still felt horribly homesick. Graham visited a couple of times a week, turning up in the hospital car park in his bubble car and taking me into Manchester for a cup of coffee and a chat. Once or twice he drove me home to visit my parents at the weekends, too, but I’m not sure that helped my feelings of homesickness as I always found it very hard to say goodbye to them.

Several weeks on, after my eight-week school-based ‘block’ was complete, I reported for ward duty for the first time with Sister Craddock, who paired me with an efficient-looking third-year student called Maggie. I was assured Maggie would ably instruct me in the arts of completing a bedpan and bottle round and giving bed baths, and I couldn’t wait to get started.

‘Most patients can manage by themselves if you draw the curtain and give them a bottle or a bedpan,’ Maggie said brightly, which immediately put me at my ease. She had already dished out half a dozen stainless steel bedpans, and she asked me to follow her round the ward and help her collect them by placing a paper cover on them and loading them on a trolley.

‘Nobody likes this job,’ she said as we went into the sluice. ‘The golden rule is to look the other way and stand back so you don’t splatter your apron.’

There was a porcelain sink on the back wall, into which Maggie tipped the contents of the pans before flushing the metal chain that was dangling beside it. The smell that rose up my nostrils as the urine and faeces were washed away made me heave, and I held my breath.

Maggie turned on the taps on either side of the sink and swilled out the pans before loading them one at a time into a sterilising unit that looked like a narrow metal washing machine. Each bedpan was blasted with boiling, steamy water before Maggie removed it with a thick linen cloth and placed it on a clean trolley ready for the next bedpan round.

‘The trick is to get it over and done with as quickly as you can,’ Maggie said. ‘Grit your teeth and just do it. If there’s one thing I’ve learned it’s that bedpans won’t clean themselves and, believe me, the smell gets worse the longer you leave it!’

I felt at ease with Maggie and hung on her every word, eager to learn from her experience. Our next task was to perform a bed bath on Mr Finch.

‘He’s a good one to start with as he lives up to his name and is as light as a bird,’ Maggie whispered as we approached his bed.

‘Good day, Nurses!’ Mr Finch beamed as Maggie pushed a trolley beside his bed and I closed the curtains around him. ‘Is it bathtime? Oh, go on then, if y’insist!’

Mr Finch put down his Daily Mirror and rubbed his hands together cheekily, eyes glinting.

‘He’s just teasing,’ Maggie said. ‘Aren’t you, Mr Finch?’

‘I am indeed,’ he tittered. ‘I’m a good boy really.’

Maggie caught my eye and winked, but I still felt slightly nervous. Mr Finch looked a bit scruffy, with nicotine-stained fingers and blackened teeth, and I shivered as I wondered what we might have to deal with under the sheets.

‘Any trouble from him, Nurse Lawton, and we’ll make sure the water is ice cold next time,’ Maggie said in an exaggerated whisper.

On the trolley Maggie had a pot of zinc and castor oil cream, a metal bowl filled with warm water and a tin of talcum powder. Mr Finch reached into his locker and produced a toilet bag containing a bar of Palmolive soap, two grey flannels and a small, thin towel.

Maggie showed me how to strip the counterpane back and pull the blanket off the patient and over an A-shaped frame she had placed at the foot of the bed.

‘Keep the top sheet in place and work underneath it as best you can,’ Maggie said quietly. ‘That’s the privacy guard.’

She demonstrated by washing and drying Mr Finch’s face first and moving on to his arms, chest and underarms without exposing an inch of flesh unnecessarily.

‘Ooh, that’s grand, Nurse,’ Mr Finch commented. ‘You’re right good at this!’

Next I helped turn Mr Finch on his side, so Maggie could wash down his back and I could dry it. He certainly was as light as a bird. He was skin and bone, in fact, and I realised he looked rather like the old man in the television comedy Steptoe and Son, which amused me.

‘Would you wash your private bits?’ Maggie said, making it sound as though she was posing a question when in actual fact she was instructing Mr Finch politely to do so.

‘Course,’ he said. ‘I tell ye what, it’s a damn sight easier t’ get m’self clean nowadays. Used to be murder when I were down the pit.’

It turned out that Mr Finch was born at the turn of the century and had worked nearly all his life at the Astley Green Colliery in Wigan, mining coal for decades until his retirement a few years earlier. He had seven children and seventeen grandchildren, and had served in both world wars.

As Maggie and I rolled him onto each side again so we could strip and re-make the bed beneath him, I thought how silly I was to have been nervous about him, and how unkind I was to have assumed he might be smelly or uncouth, just because he was old and had spent his life working his fingers to the bone.

I loved getting to know such interesting folk and I soon realised that once people are stripped bare in a hospital bed, that’s when you find out who they really are. This realisation struck me as so profound that I wrote it down in my notebook when I returned to my room after tea, because I never wanted to forget it. As I did so, I realised with some satisfaction that despite still being plagued by homesickness, and despite feeling mentally and physically drained at the end of the day, I was doing my very best and I was slowly starting to find my feet.

I fell into an extremely deep sleep that night. Sister Mary Francis would have called it the ‘sleep of the just’, but my much-needed slumber was suddenly interrupted when an alarm bell rang out. In my dream I saw a ghostly-white patient desperately pressing a red emergency buzzer. I couldn’t see the patient’s face and I didn’t know which ward he was on or what was wrong with him. I could see him holding out his hands to me, but I couldn’t get close enough to help him because I was stuck behind a pile of textbooks that towered higher and higher the more I tried to move forwards. Physiology. Anatomy. Dietetics. Bacteriology. The words swarmed, distorting my vision.

‘Wake up, Linda! Get up quick!’ It was Anne’s voice, and she was hammering on my door. ‘There’s a fire! Get up!’

I stumbled out of bed, my heart thumping. The alarm in my dream suddenly got louder and louder. My door was open now and I could see nurses running towards the emergency exit along the corridor. The fire alarm was blasting out as I grabbed my dressing gown and ran, barefoot, into the arms of a burly fireman.

‘Steady now!’ he grinned. ‘There’s no need to panic. Just make your way outside calmly and we should be able to get you back inside in no time at all.’

We were told a small fire had broken out on the opposite side of the nurses’ home, which was soon contained. This news travelled quickly around the car park, where I stood shivering in my nightie and dressing gown, still feeling drugged by sleep. Eventually another very handsome fireman led me back to my room, which he was in the process of checking over when the home sister stuck her nose round my door.

‘See that you remove that poster in the morning,’ she said huffily, pointing to my beloved black and white John Lennon portrait taped boldly above my bed. ‘You know quite well it is forbidden to decorate the walls.’

The fireman flashed me a dazzling smile and rolled his eyes behind her back before wishing me a very good night.

‘Do you know, I think I’ll always have a soft spot for firemen,’ I told Anne dreamily at breakfast the next morning.

‘All the more reason to work hard,’ Anne replied with a wink. ‘Everyone knows firemen have a soft spot for nurses, too.’

‘You’re right,’ I smiled. ‘Perhaps I’ve chosen the right career after all!’

Chapter Three

‘I didn’t expect to be looking after people who are actually ill’

‘Lawton, attend to Mrs Roache in bed thirteen,’ Sister Bridie ordered. I hated the way she addressed us by our surnames, as if we were in the Army. I leapt to attention, nevertheless.

I was now a good few months into my first year of training. So far I’d had a trouble-free start to my nursing career. Soon after the eight weeks of study with Mr Tate, which were punctuated by visits to wards and units, I completed my first placement, which happened to be at the eye hospital over the road in Nelson Street.

We had no say in where we were sent for work experience, but I had no complaints and was quite happy dishing out eye drops, wiping down lockers and fetching cups of tea for patients, while at the same time learning how to sterilise equipment, organise the linen cupboard and generally keep Sister happy.

The only part of the work that worried me at the eye hospital was using the sterilising equipment. The machine was different to the bedpan steriliser I’d become accustomed to operating in the sluices at the main hospital. This one stood on a substantial trolley that was positioned right in the middle of the ward. It looked harmless enough, shaped like a small stainless-steel oven, but it hissed and bubbled as loudly as a witch’s cauldron.

I’d seen other nurses adeptly sterilising kidney bowls, syringes and needles, seemingly oblivious to the dangers of the swirling clouds of hot steam the contraption emitted whenever it was opened, but I was scared to death the first time I had to operate it by myself, jumping back in fright as the sweltering steam billowed into my face. I practically threw the instruments in, pulling my hand away and slamming the door shut in record time. It was a miracle I hadn’t been burned, especially as I had to repeat the process in reverse five minutes later, retrieving my poker-hot equipment with a pair of Cheatle forceps.

Needless to say, I soon got used to the steriliser, and by the time I left the eye unit I think I could have operated it in my sleep. My next placement was to be on Sister Bridie’s surgical ward.

‘Are you looking forward to it?’ Graham asked me the night before I was to start there, when he picked me up in his car and took me out for a coffee at a little snack bar in Piccadilly Gardens, up near the station.

‘Oh yes,’ I replied. ‘Very much so. The eye unit was good experience but it wasn’t exactly exciting.’ The fierce steriliser had been the only thing that made my pulse quicken. ‘I’m ready for the next challenge. A surgical ward should be very interesting. It’s a female ward and I expect women need surgery for all sorts of reasons. It’ll be good to deal with more than just eyes.’

‘That’s my little nurse!’ Graham said encouragingly.

‘I’m a bit worried about Sister Bridie, though,’ I admitted. ‘She’s Irish and a spinster, so I hear, and she seems terribly strict and bossy.’

‘Don’t fret. You were worried about the Matron to begin with,’ Graham reminded me, ‘and I’ve hardly heard you mention her since.’

‘That’s true,’ I said thoughtfully. ‘I guess I’ve learned that Miss Morgan leaves you alone as long as you keep your head, and your skirt length, down!’

‘Glad to hear it,’ he smiled.

‘Besides, you always know when Matron is on the warpath, as word spreads like Chinese whispers. “Matron’s coming, pass it on,” we say, and usually the entire ward is on best behaviour before she has set foot through the main doors.’

Sister Bridie worried me more, I realised. ‘I’ll be seeing her on a daily basis on the surgical ward, come what may. I’ve heard she used to be on the men’s cardiac ward, and she shouted so loudly at the student nurses that she nearly gave the patients another heart attack.’

Graham laughed and I joined in, seeing through his eyes how funny this was. He was a marvellous help to me. Despite the camaraderie I shared with Linda and the other girls and the endless encouragement offered by my mum on the phone and on my occasional weekend visits home, it was Graham who kept me going, always willing to drive up to the hospital two or even three times a week to see me and let me unload about my day.

Sometimes I cried in his arms as we huddled together in the hospital car park, because I was tired out and I missed him and my home so much. Graham always provided a good reason for me to keep my chin up and carry on. ‘Think how you’ll feel when you’re a qualified SRN,’ he would say. ‘We’ll be able to get married and get a place of our own! You’ve come this far. You can do it, Linda. I’m so proud of you. You were made for this job.’

Now he commented: ‘I can’t imagine you giving Sister Bridie any reason whatsoever to shout at you.’

I hoped he was right, and his words helped set my mind at ease a little. All I had to do was obey orders and work hard, and I had nothing to fear. ‘What doesn’t kill me will make me stronger,’ I thought.