Полная версия

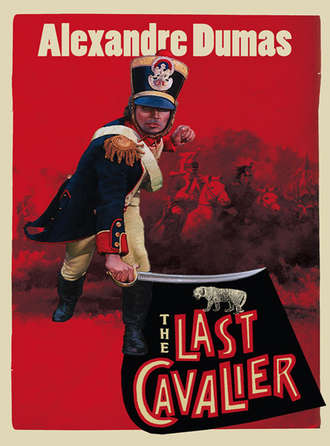

The Last Cavalier: Being the Adventures of Count Sainte-Hermine in the Age of Napoleon

“Yes.”

“Do you have the six hundred thousand francs?”

“Yes, I do,” said Bourrienne.

Josephine clapped her hands like a child just relieved of its penitence.

“But,” Bourrienne added, “for the love of God, don’t run up any more debts, or at least be reasonable.”

“What do you call reasonable debt, Bourrienne?” asked Josephine.

“How do you expect me to answer that? The best thing would be to run up no debt at all.”

“You surely know that is impossible, Bourrienne,” Josephine answered with conviction.

“Perhaps fifty thousand francs. Maybe one hundred thousand.”

“But, Bourrienne, once these debts have been paid, and you are confident that you can pay them all with the six hundred thousand francs…”

“Yes?”

“Well, my suppliers will then no longer refuse me credit.”

“But how about him?”

“Who?”

“The First Consul. He swore that these would be the last debts he would pay on your account.”

“Just as he also swore last year,” said Josephine with her charming smile.

Bourrienne looked at her in stupefaction. “Truly,” he said, “you frighten me. Give us two or three years of peace and the few measly millions we brought back from Italy will be exhausted; yet you persist.… If I have any advice to give you, it is to allow him some time to get over this bad mood of his before you see him again.”

“But I can’t! Because I really must see him right away. I have set up a meeting this morning for a compatriot from the colonies, a family friend, the Comtesse de Sourdis and her daughter, and not for anything in the world would I have him fly into a fit of rage in the presence of these fine women, women whom I met in society, on their first visit to the Tuileries.”

“What will you give me if I keep him up here, if I get him even to have his lunch here, so that he’d have no reason to come down to your rooms until dinnertime?”

“Anything you want, Bourrienne.”

“Well, then, take a pen and paper, and write in your own lovely little handwriting.…”

“What?”

“Write!”

Josephine put pen to paper, as Bourrienne dictated to her: “I authorize Bourrienne to settle all my bills for the year 1800 and to reduce them by half or even by three quarters if he judges it appropriate.”

“There.”

“Date it.”

“February 19, 1801.”

“Now sign it.”

“Josephine Bonaparte.… Is everything now in order?”

“Perfectly in order. You can return downstairs, get dressed, and welcome your friend without fear of being disturbed by the First Consul.”

“Obviously, Bourrienne, you are a charming man.” She held out the tips of her fingernails for him to kiss, which he did respectfully.

Bourrienne then rang for the office boy, who immediately appeared in the doorway. “Landoire,” Bourrienne said, “inform the steward that the First Consul will be taking lunch in his office. Have him set up the pedestal table for two. We shall let him know when we wish to be served.”

“And who will be having lunch with the First Consul, Bourrienne?”

“No business of yours, so long as it’s someone who can put him in a good mood.”

“And who would that be?”

“Would you like him to have lunch with you, madame?”

“No, no, Bourrienne,” Josephine cried. “Let him have lunch with whomever he chooses, just so he does not come down to me until dinner.” And in a cloud of gauze she fled the room.

Not two minutes later, the door to the study burst open and the First Consul strode straight to Bourrienne. Planting his two fists on the desktop, he said, “Well, Bourrienne, I have just seen the famous George Cadoudal.”

“And what do you think of him?”

“He is one of those old Bretons from the most Breton part of Brittany,” Bonaparte replied, “cut from the same granite as their menhirs and dolmens. And unless I’m sadly mistaken, I haven’t seen the last of him. He’s a man who fears nothing and desires nothing, and men like that … the fearless are to be feared, Bourrienne.”

“Fortunately such men are rare,” said Bourrienne with a laugh. “You know that better than anyone, having seen so many reeds painted to look like iron.”

“But they still blow in the wind. And speaking of reeds, have you seen Josephine?”

“She has just left.”

“Is she satisfied?”

“Well, she no longer carries all her Montmartre suppliers on her back.”

“Why did she not wait for me?”

“She was afraid you would scold her.”

“Surely she knows she cannot escape a scolding!”

“Yes, but gaining some time before facing you is like waiting for a change to good weather. Then, too, at eleven o’clock she is to receive one of her friends.”

“Which one?”

“A Creole woman from Martinique.”

“Whose name is?”

“The Comtesse de Sourdis.”

“Who are the Sourdis family? Are they known?”

“Are you asking me?”

“Of course. Don’t you know the peerage list in France backward and forward?”

“Well, it’s a family that has belonged to both the church and the sword as far back as the fourteenth century. Among those participating in the French expedition to Naples, as best as I can recall, there was a Comte de Sourdis who accomplished marvelous feats at the Battle of Garigliano.”

“The battle that the knight Bayard managed to lose so effectively.”

“What do you think about Bayard, that ‘irreproachable and fearless’ knight?”

“That he deserved his good name, for he died as any true soldier must hope to die. Still, I don’t think much of all those sword-swingers; they were poor generals—Francis I was an idiot at Pavia and indecisive at Marignan. But let’s get back to your Sourdis family.”

“Well, at the time of Henri IV there was an Abbesse de Sourdis in whose arms Gabrielle expired; she was allied with the d’Estrée family. In addition, a Comte de Sourdis, serving under Louis XV, bravely led the charge of a cavalry regiment at Fontenoy. After that, I lose track of them in France; they probably went off to America. In Paris, they live behind the old Hôtel Sourdis on the square Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois. There is a tiny street named Sourdis that runs from the Rue d’Orleans to the Rue d’Anjou in the Marais district, and there’s the cul-de-sac called Sourdis off the Rue des Fossés-Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois. If I’m not mistaken, this particular Comtesse de Sourdis, who in passing I must say is very rich, has just bought a lovely residence on Quai Voltaire and is living there. Her house opens onto the Rue de Bourbon, and you can see it from the windows in the Marsan pavilion.”

“Perfect! That’s how I like to be answered. It seems to me that these de Sourdises are closely related to those living in Saint-Germain.”

“Not really. They are close relatives of Dr. Cabanis, who shares, as you know, our political religion. He is even the girl’s godfather.”

“That improves things. All those dowagers who live in Saint-Germain are not good company for Josephine.”

At that moment Bonaparte turned around and noticed the pedestal table. “Had I said that I would be having lunch here?” he asked.

“No,” Bourrienne answered, “but I thought it would be better if today you had lunch in your study.”

“And who will be doing me the honor of having lunch with me?”

“Someone I have invited.”

“Given the way I was feeling, you had to be very sure that the person would please me.”

“I was quite sure.”

“And who is it?”

“Someone who came from far away and arrived at the Tuileries while you were with George in the reception room.”

“I had no other meetings scheduled.”

“This person came without a scheduled meeting.”

“You know that I never receive anyone without a letter.”

“This person you will receive.”

Bourrienne got up, went to the officers’ room, and simply said, “The First Consul is back.”

At those words, a young man rushed into the First Consul’s study. Although he was only about twenty-five or twenty-six years old, he was wearing the casual clothes of a general. “Junot!” Bonaparte exclaimed joyously.

“By God, you were quite right to say that this man did not need a letter! Come here, Junot!” The young general did not hesitate, but when he tried to take Bonaparte’s hand and raise it to his lips, the First Consul opened his arms and pulled Junot tightly to his breast.

Among the many young officers who owed their careers to Bonaparte, Junot was one of those he loved the most. They had met during the siege of Toulon, when Bonaparte was commanding the battery of the sansculottes. He had asked for someone who could write beautifully, and Junot, stepping from the ranks, introduced himself. “Sit down there,” Bonaparte said, pointing to the battery’s breastwork, “and write what I dictate.” Junot of course obeyed.

He was just finishing the letter when a bomb, tossed by the English, exploded ten steps away and covered him with dirt. “Good!” said Junot with a laugh. “How convenient! We didn’t have any sand to blot the ink.” Those words made his fortune.

“Would you like to stay with me?” Bonaparte asked. “I shall take care of you.” And Junot answered, “With pleasure.” From the outset the two men understood each other.

When Bonaparte was named general, Junot became his aide-de-camp. When Bonaparte was placed on reserve duty, the two young men shared their poverty, living off the two or three hundred francs that Junot received each month from his family. After the 13th Vendémiaire, Bonaparte had two other aides-de-camp, Muiron and Marmont, but Junot remained his favorite.

Junot participated in the Egyptian campaign as a general. So, to his great regret, he had to part with Bonaparte. He performed feats of courage at the battle of Fouli, where he shot dead the leader of the enemy army with his pistol. When Bonaparte left Egypt, he wrote to Junot:

I am leaving Egypt, my dear Junot. You are too far away from where we are embarking for me to take you along with me. But I am leaving orders with Kléber for you to leave in October. Finally, wherever I am, whatever my position, please know that I will always give you proof positive of our close friendship.

Good-bye and best wishes,

Bonaparte

On his way back to France on an old cargo ship, Junot fell into the hands of the English. Since then, Bonaparte had heard no news of his friend, so Junot’s unexpected appearance created quite a stir in Bonaparte’s quarters.

“Well, finally you’re back!” exclaimed the First Consul. “I knew you idiotically let yourself be caught by the English by remaining so long in Egypt. What I don’t know is why you waited five months when I had asked you to leave as soon as possible.”

“Good heavens! Because Kléber would not let me leave. You have no idea how difficult he made things for me.”

“He no doubt feared that I’d have too many of my friends in my ranks. I know no love was lost between us, but I never thought he’d demonstrate his enmity in such a petty way. Plus, he wrote a letter to the Directory—do you know about that? What’s more,” Bonaparte added, raising his eyes heavenward, “his tragic end closed all our accounts, and both France and I have undergone a major loss. But the irreparable loss, my friend, is the loss of Desaix. Ah, Desaix! Such a grave misfortune to have smote our country.”

Totally absorbed in his pain, Bonaparte paced up and down a moment without saying a word. Then, suddenly, he stopped in front of Junot. “So, what do you want to do now? I have always said that I would furnish proof of my friendship when I could. What are your plans? Do you want to serve?”

Then, the look in his eyes difficult to read, Bonaparte asked jovially, “Would you like me to have you join the Rhine army?”

Junot cheeks grew flushed. “Are you trying to get rid of me?” he said. After a pause, he continued: “If such are your orders, I shall be happy to show General Moreau that the officers in the army of Italy have not forgotten their work in Egypt.”

“Well,” said the First Consul with a laugh, “my cart is getting before my horse! No, Monsieur Junot, no, you’ll not leave me. I admire General Moreau a great deal, but not so much that I would give him one of my best friends.” Then, his brow creased, he continued more seriously: “Junot, I’m going to give you command of Paris. It’s a position of trust, especially just now, and I could not make a better choice. But”—he glanced around as if he feared someone might be listening—“you must give it some thought before you accept. You’ll need to age ten years, because the position requires not only gravity and prudence to the extreme; it also demands the utmost attention to everything related to my safety.”

“General,” Junot exclaimed, “on that score.…”

“Silence, my friend, or at least speak more softly,” Bonaparte said. “Yes, you must watch over my safety. For I am surrounded by danger. If I were still simply the General Bonaparte I was before and even after the 13th Vendémiaire, I would make no effort to avoid danger. In those days my life was my own; I knew its worth, which was not very much. But now my life is no longer my own. I can say this only to a friend, Junot: My destiny has been revealed to me. It is the destiny of a great nation, and that is why my life is threatened. The powers that hope to invade France and divide it up would like to have me out of their way.”

Raising his hand to his brow as if he were trying to chase away a troublesome thought, he remained pensive for a moment. Then, his mind moving rapidly from one idea to another—he’d sometimes entertain twenty different ideas at once—Bonaparte resumed: “So, as I was saying, I shall name you commander of Paris. But you need to get married. That would be appropriate not only for the dignity of the position, but it is also in your own best interest. And by the way, be careful to marry only a rich woman.”

“Yes, but I would like her to be attractive as well. There’s the problem: All heiresses are as ugly as caterpillars.”

“Well, set to work immediately, for I am appointing you commander of Paris as of today. Look for an appropriate house, one not too far from the Tuileries, so that I can send for you whenever I need you. And look around; perhaps you can choose a woman from the circle in which Josephine and Hortense move. I would suggest Hortense herself, but I believe she loves Duroc, and I would not want to go against her own inclinations.”

“The First Consul is served!” said the steward, carrying in a tray.

“Let’s sit down,” said Bonaparte. “And in a week from now, you shall have rented a house and chosen a wife!”

“General,” said Junot, “while I don’t doubt I can find a house in a week, I would like to request two weeks for the wife.”

“Agreed,” said Bonaparte.

X Two Young Women Put Their Heads Together

AS THE TWO COMPANIONS AT ARMS were sitting down at their table, Madame la Comtesse and Mademoiselle Claire de Sourdis were announced to Madame Bonaparte.

The women embraced and, gracefully grouping themselves, they inquired after each other’s health and spoke of the weather, as was the mode of aristocratic society. Madame Bonaparte then had Madame de Sourdis sit beside her on a chaise longue, while Hortense took it upon herself to show Claire around the palace, as she was visiting for the first time.

The two girls, though about the same age, made a charming contrast. Hortense was blonde, fresh as a daisy, velvety as a peach. Her golden hair fell down to her knees, and her arms and hands were somewhat thin, for she still awaited Nature’s last touch to turn her into a woman. In her graceful appearance she combined both French vivaciousness and Creole sweetness. And, to complete the charming picture, her blue eyes shone with infinite gentleness.

Her companion had no cause for jealousy in regard to grace and beauty. Both girls were Creoles, but Claire was taller than her friend, and she had the dark complexion that Nature reserves for the southern beauties she seems to favor. Claire had sapphire blue eyes, ebony hair, a waist so slender two hands could span it, and hands and feet as tiny as a child’s.

Both had received excellent educations. Hortense’s education, interrupted by her forced apprenticeship until her mother got out of prison, had been organized so intelligently and assiduously that you would not imagine it had ever been interrupted at all. She could draw very nicely, was an excellent musician, indeed composed music, and wrote romantic poetry, some of which has been passed down to us, not simply because of the author’s elevated position but rather because of its intrinsic value. In fact, both girls were painters, both were musicians, and both spoke two or three foreign languages.

Hortense showed Claire her study, her sketches, her music room, and her aviary. Near the aviary, they sat down in a little boudoir that had been painted by Redouté. There they spoke about society parties, now beginning to reappear more brilliant than ever; about balls, which were vigorously starting up again; and about handsome, accomplished dancers. They talked about Monsieur de Trénis, Monsieur Laffitte, Monsieur d’Alvimar, and both Coulaincourts. They complained about the necessity, at every ball, to dance at least one gavotte and one minuet. And two questions arose quite naturally.

Hortense asked, “Do you know Citizen Duroc, my stepfather’s aide-de-camp?”

And Claire wondered, “Have you had the opportunity to meet Citizen Hector de Sainte-Hermine?”

Claire did not know Duroc.

Hortense did not know Hector.

Hortense more than nearly dared admit that she loved Duroc, for her stepfather, who himself greatly admired Duroc, had given his blessing. Indeed, Duroc was one of those young generals for whom the Tuileries was such a proving ground in those days. He was not yet twenty-eight, his manners were quite distinguished, and he had large but not deeply set eyes. He was taller than average, slender and elegant.

A shadow hovered over their love, however. For while Bonaparte supported it, Josephine did not. She wanted Hortense to marry Louis, one of Napoleon’s younger brothers.

Josephine had two declared enemies within Napoleon’s family, Joseph and Lucien, who had very nearly obtained Bonaparte’s agreement, on his return from Egypt, that he would never see Josephine again. Since his marriage to Josephine, Bonaparte’s brothers were constantly pressing him to divorce, on the pretext that a male child was necessary to realize his ambitious plans. It was an easy argument for them to make, since it appeared they were working against their own interests.

Joseph and Lucien were both married, Joseph perfectly and appropriately. He had married the daughter of Monsieur Clary, a rich merchant from Marseille, and was thus Bernadotte’s brother-in-law. Clary had a third daughter, perhaps more charming than her sisters, and Bonaparte asked for her hand in marriage. “Heavens, no,” the father answered. “One Bonaparte in my family is enough.” If he had agreed, the honorable merchant from Marseille would one day have found himself father-in-law to an emperor and two kings.

As for Lucien, he had made what society calls an unequal marriage. In 1794 or 1795, when Bonaparte was still known only for having taken Toulon, Lucien accepted the position of quartermaster in the little village of Saint-Maximin. A Republican who changed his name to Brutus, Lucien would not permit saints’ names of any kind in his village. So he had rebaptized Saint-Maximin; the village became Marathon. Citizen Brutus, from Marathon. That had a nice ring to it, he thought.

Lucien-Brutus was living in the only hotel in Saint-Maximin-Marathon. The hotelkeeper was a man who had given no thought to changing his name, Constant Boyer, or that of his daughter, an adorable creature named Christine: Sometimes such flowers grow in manure, such pearls in mud.

Saint-Maximin-Marathon offered Lucien-Brutus no society life and no distractions, but he soon discovered he needed neither, because he had found Christine Boyer. Only Christine Boyer was as wise as she was beautiful, and Lucien realized there was no way he could make her his mistress. So, in a moment of love and boredom, Lucien made her his wife. Christine Boyer became not Christine Brutus, but Christine Bonaparte.

The general of the 13th Vendémiaire, who was beginning to see his fortune clearly, grew furious. He swore he would never forgive the husband, never receive the wife, and he sent both of them to a little job in Germany. Later he softened; he did see the woman, and he was not displeased to see his brother Lucien Brutus become Lucien Antoine before the 18th Brumaire.

Lucien and Joseph both became the terror of Madame Bonaparte. By marrying Bonaparte’s nephew Louis to her daughter, Josephine hoped to interest him in her own fortune and to strengthen her protection against the two brothers.

Hortense resisted with all her might. At that time, Louis was quite a handsome young man, if barely twenty years old, with nice eyes and a kind smile—he looked rather like his sister Caroline, who had just married Murat. While he was not at all in love with Hortense, although he did not find her unattractive, he was too passive to resist the forces at play. Nor did Hortense hate Louis. But she was in love with Duroc.

Her little secret gave Claire de Sourdis confidence. She too ended up admitting something, precious little though it was to admit.

She too was in love, if we can call it love. It would be more appropriate to say that she was in thrall to an image, a mystery in the shape of a handsome young man.

He was twenty-three or twenty-four, with blond hair and dark eyes. His features seemed almost too regular for a man, and his hands were as elegant as a woman’s. He was put together so precisely, each part of him so completely in harmony with the whole, that one could readily see that the outward form of the man, however fragile in appearance, hid Herculean strength. Even before the time of Chateaubriand and Byron, who created darkly romantic heroes like René and Manfred, he bore a troubled brow whose pallor bespoke a strange destiny. For terrible legends were attached to his family name—legends known only imperfectly, but they came stained with blood. Yet nobody had ever seen him parade an air of exaggerated mourning, like so many who had lost so much during the Republic, and never had he made show of his pain at dances and salons and social gatherings. In fact, when he did appear in society, he had no need of any such affectations to try to attract attention. People just naturally looked at him. Usually, though, he eschewed the pastimes of his hunting and travel companions, who had never yet managed to drag him to one of those youthful parties which even the most rigid agree to attend sooner or later. And nobody remembered ever having seen him laugh aloud and openly the way most young people do, or even having seen him smile.

There had long been alliances between the Sainte-Hermine and the Sourdis families, and, as is customary in such noble houses, the memory of those alliances remained important. So when by chance young Sainte-Hermine had come to Paris, he had never failed, since Madame de Sourdis had come back from the colonies, to visit her, for he observed the demands of protocol, and never had his visits been other than formal.

The two young people had had occasion to meet, in society, over the past several months. Besides the polite greetings they exchanged, however, words had been spoken sparingly, especially by the young man. But their eyes had spoken eloquently. Hector apparently did not hold the same control over his eyes as he did over his words, and each time he encountered Claire, his gaze made known how lovely he found her and how perfectly she matched all his heart’s desires.

At their first meetings Claire had been moved by his expressive eyes, and since Sainte-Hermine seemed to her an accomplished gentleman in every way, she had permitted herself to look at him too less guardedly. She had also hoped that he would invite her to dance so that a whispered word or the pressure of his hand might affirm the meaning she’d read in his gaze. But, strangely for the time, Sainte-Hermine, the gentleman who took fencing lessons with Saint-Georges and who could shoot a pistol as well as Junot or Fournier, did not dance.