Полная версия

The First Iron Lady: A Life of Caroline of Ansbach

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017

Copyright © Matthew Dennison 2017

Matthew Dennison asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Cover images Royal Collection Trust/© Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2017

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008121990

Ebook Edition © August 2017 ISBN: 9780008122010

Version: 2018-08-20

Dedication

For Gráinne, with love

‘Behold, thou art fair, my love; behold, thou art fair … Thou art all fair, my love; there is no spot in thee.’

Song of Solomon

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

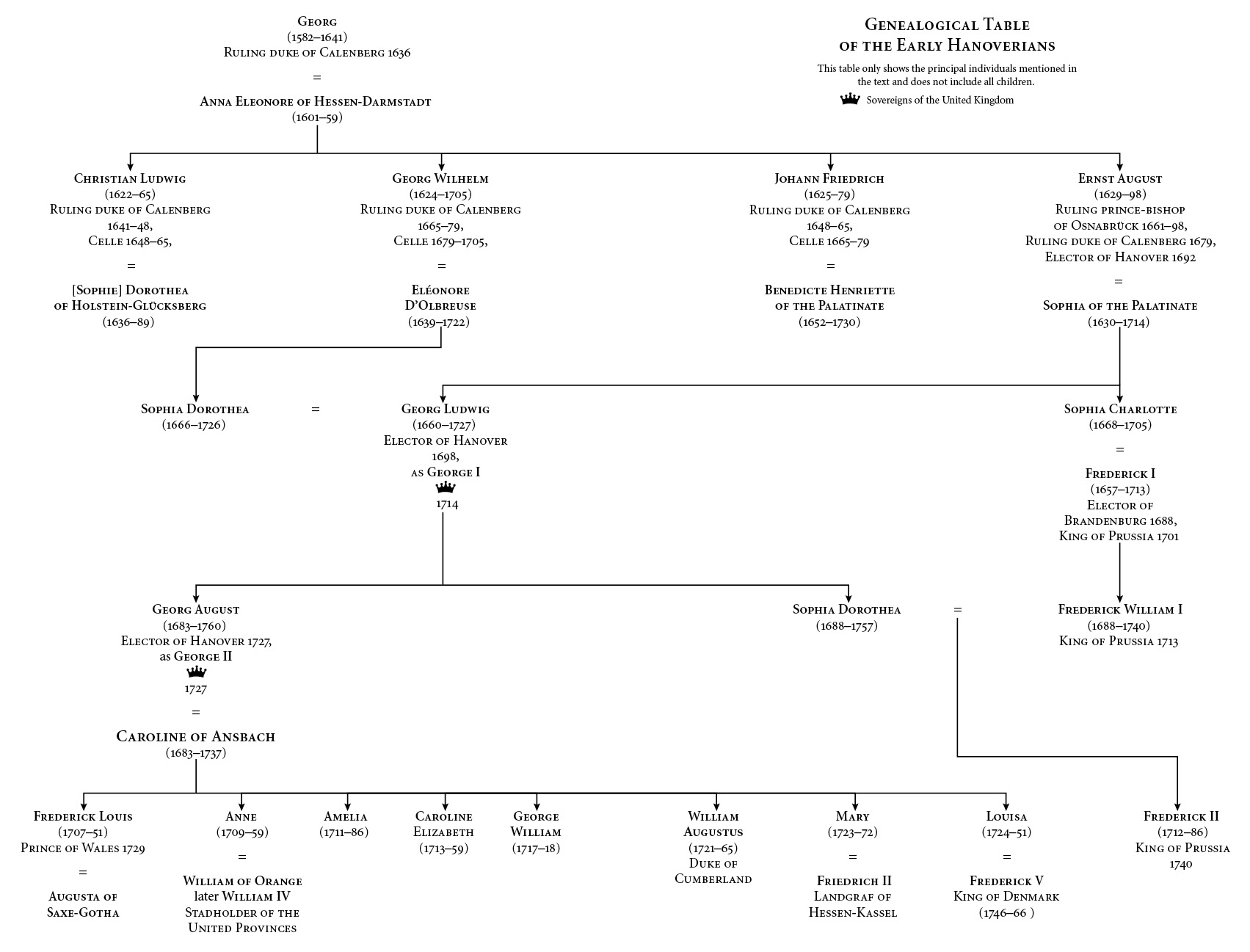

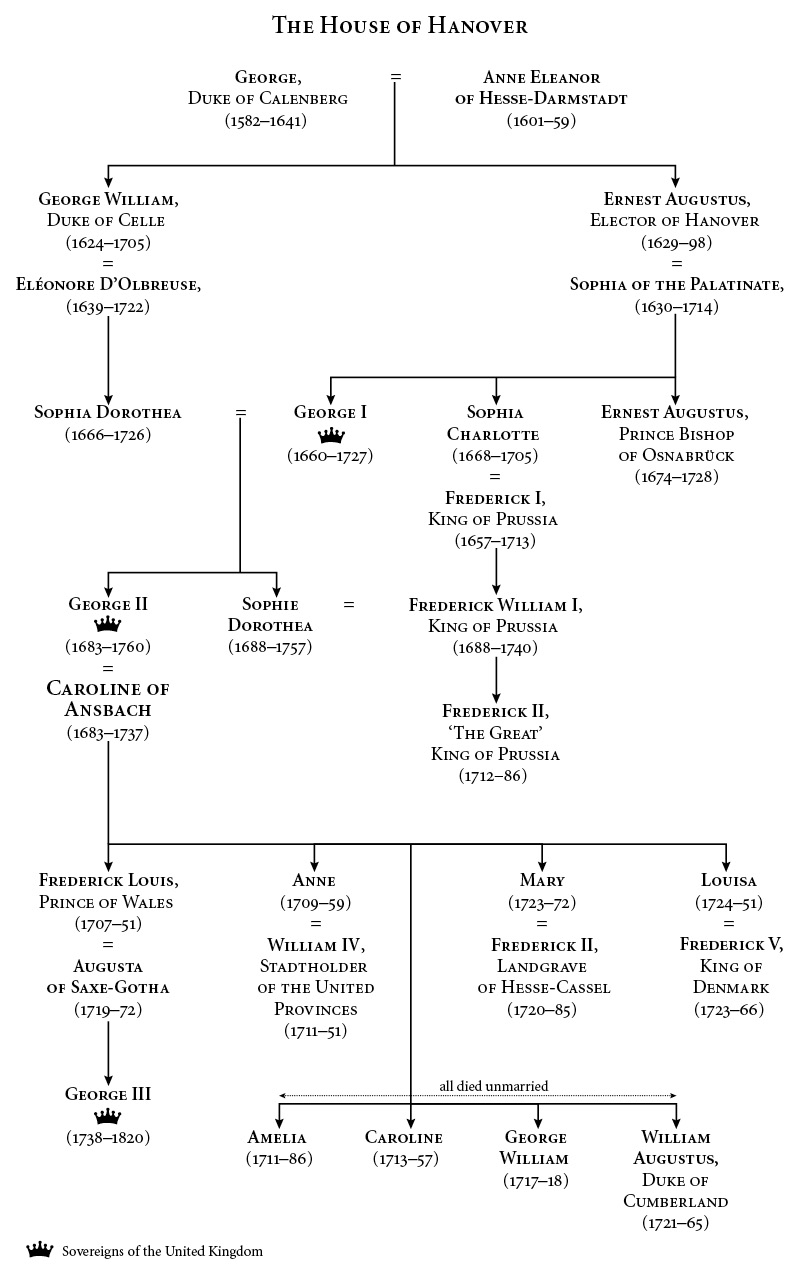

Family Trees

Epigraph

Introduction

Prologue: ‘Halliballoo!’

PART ONE: GERMANY

I Princess of Ansbach: ‘Bred up in the softness of a Court’

II Electoral Princess: ‘The affections of the heart’

PART TWO: BRITAIN

I Princess of Wales: ‘Majesty with Affability’

II Leicester House: ‘Not a Day without Suffering’

III Queen: ‘Constancy and Greatness’

Afterword

Acknowledgements

Notes

Bibliography

Picture Section

Index

Also by Matthew Dennison

About the Publisher

Epigraph

‘The darling pleasure of her soul was power.’

Lord Hervey, Memoirs

‘She loved the real possession of power rather than the show of it, and whatever she did herself that was either wise or popular, she always desired that the King should have the full credit as well as the advantage of the measure, conscious that, by adding to his respectability, she was most likely to maintain her own.’

Walter Scott on Caroline of Ansbach, The Heart of Midlothian, 1818

Introduction

History has forgotten Caroline of Ansbach. The astuteness of her political manoeuvrings; her patronage of poets, philosophers and clerics; her careful management of her peppery husband George II; the toxic breakdown of her relationship with her eldest son, Frederick; her reputation as Protestant heroine; even the legendary renown of her magnificent bosom – ‘her breasts they make such a wonder at’ – have all escaped posterity’s radar.1

Her contemporaries understood her as the power behind George II’s throne. One lampoon taunted, ‘You may strutt, dapper George, but ’twill all be in vain;/We know ’tis Caroline, not you, that reign.’2 She was the first Hanoverian queen consort. On her arrival in London from Germany in October 1714, following the accession of her father-in-law as George I, she became the first Princess of Wales since 1502, when Catherine of Aragon married Prince Arthur, short-lived elder brother of the future Henry VIII.

Blonde, buxom, with a rippling laugh and a raft of intellectual hobbyhorses, in 1714 she was also the mother of four healthy children. Her fertility was in stark contrast to the record of later Stuarts: barren Catherine of Braganza, Portuguese wife of Charles II; childless Mary II and Queen Anne, whose seventeen pregnancies fatally undermined her health but failed to produce a single healthy heir. Early praise of Caroline celebrated her fecundity. Poet Thomas Tickell’s Royal Progress of 1714 invites the reader to marvel at ‘the opening wonders’ of George I’s reign: ‘Bright Carolina’s heavenly beauties trace,/Her valiant consort and his blooming race./A train of kings their fruitful love supplies.’ Those magnificent breasts, so remarked upon by onlookers and commemorated in a formidable posthumous portrait bust by sculptor John Michael Rysbrack, were an obvious metaphor, key assets for the mother of a new dynasty.3

With conventional hyperbole, the future Frederick the Great addressed her as ‘a Queen whose merit and virtues are the theme of universal admiration’.4 Voltaire acclaimed her as ‘a delightful philosopher on the throne’.5 Her niece, the Margravine of Bayreuth, praised her ‘powerful understanding and great knowledge’, and an Irish clergyman noted in her ‘such a quickness of apprehension, seconded by a great judiciousness of observation’.6 In his Marwnad y Frenhines Carolina (‘Elegy to Queen Caroline’), London-based Welsh poet Richard Morris called her ‘ail Elisa’, a second Eliza or Elizabeth.7 Jane Brereton’s The Royal Heritage: A Poem, of 1733, made another Tudor connection, linking the intelligent Caroline with Henry VIII: ‘O Queen! More learn’d than e’er Britannia saw,/Since our fam’d Tudor to the Realm gave Law.’8 More simply, her girlhood mentor described her company as ‘reviving’.9 Meanwhile Alexander Pope, a sceptical observer, was responsible for several critical poetic imaginings of Caroline. These include the personification of cynical adroitness he offered in Of the Characters of Women – ‘She, who ne’er answers till a Husband cools,/Or, if she rules him, never shows she rules;/Charms by accepting, by submitting sways’ – a view in line with Lord Hervey’s statement that she ‘governed [George Augustus] by dissimulation, by affected tenderness and deference’.10 Caroline’s dissatisfaction with the conventional limits of a consort’s role – her reluctance to be defined by gynaecological prowess or her appearance – inspired conflicting responses among her contemporaries, but lies at the heart of her remarkable story.

Caroline is the heroine of sparkling memoirs by her vice chamberlain, John, Lord Hervey, written shortly after the events they describe; she is at the heart of published memoirs and diaries by two of her closest female attendants, Mary, Lady Cowper, and Charlotte Clayton, afterwards Lady Sundon. Like the majority of primary sources, none is wholly reliable. In 1900, Caroline’s first full-length biography, Caroline the Illustrious, by W.H. Wilkins, lauded its subject as central to the successful transfer of the electors of Hanover to Britain’s throne. Unlike the author, reviewers glimpsed Caroline and her world through a prism of Victorian disapproval, firmly thrusting her back into a disreputable past. ‘She died as she lived, a strange mixture of cynicism and clairvoyance,’ commented the Spectator opaquely. ‘Herself the model of virtue, she spent her life in an atmosphere of vulgar vice.’11 In 1939, a biography by Rachel Arkell again acclaimed Caroline’s intellect and acuity. Both authors drew on source material in German archives subsequently damaged by wartime bombing. Published in the same year as Arkell’s account, Peter Quennell’s Caroline of England is lighter stuff, in part a portrait of robust Augustan London dandled in the face of Nazi aggression.

And then a curtain descended. Like her husband George II, in 1973 the only British monarch not to merit a volume in Weidenfeld & Nicolson’s popular ‘Life and Times’ series, Caroline again fell out of view. Her reputation suffered eclipse by a better-known Queen Caroline, George IV’s despised wife Caroline of Brunswick. The latter’s rackety story invests her husband’s history with tabloid sensationalism. Caroline of Ansbach’s impact on her demanding spouse came closer to that of Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha on Queen Victoria or Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon on George VI, an admonitory, popularising presence, albeit exercised more covertly than Albert’s earnest pedagogy.

Such wholesale neglect is the more surprising given that, in her lifetime, Caroline inspired reverence, adulation, sneering and hatred. A poem written to celebrate her coronation in 1727 pictured her unconvincingly as the embodiment of ‘Innocence and Mildness …/The sure Foundation of domestic Love’; a decade later, Richard West’s A Monody on the Death of Queen Caroline wrongly predicted ‘thy name, great Queen, shall … live in every age’.12 By contrast her father-in-law described her as a ‘she-devil’ or ‘fury’. She was burnt in effigy on the streets of London. A rancorous elderly courtier recoiled even from her appearance, her ‘face frightfull, her eyes very small & green like a Cat & her shape yet worse’.13

To others she was a poster girl for Protestant piety and, in at least one case, no less than the earthly mediator of a Protestant God: ‘Th’Almighty seeing so much Christian Grace,/And how, on Earth, she ran the heavenly Race;/Has constituted ROYAL CAROLINE/His Agent here, to make his Glory shine.’14 A panegyric stated, ‘it appears to the admiration even of those who saw her at all times and seasons, and in every hour when the Mind is most unguarded, that her Majesty was always in a very eminent manner the same great and good Person’.15 A politician’s wife referred to Caroline’s ‘ears … always open to the cries of the distressed’.16

The truth is seldom one-sided, and flattery distorts. Caroline was villain and victim, sinner as well as saint, fond and loving but a good hater too. Keenly interested in politics, in the decade until her death she played a part in George II’s government, while never revealing to that prickly and self-important prince the full extent of her interference when his back was turned. She had no truck with political impartiality. Whig politics – a Protestant, pro-parliamentary outlook – had placed her husband’s family on the throne, and in her relationship with pre-eminent politician of the period, Robert Walpole, satirised on her account as ‘the Queen’s Minister’, Caroline was as fully a Whig partisan as her husband or her father-in-law George I. ‘We are as much blinded in England by politicks and views of interest, as we are by mists and fogs, and ’tis necessary to have a very uncommon constitution not to be tainted with the distempers of our climate,’ wrote Caroline’s contemporary Lady Mary Wortley Montagu.17 Caroline shared the blindness of her adopted countrymen. ‘I am a woman and I delude myself,’ she once claimed with careful disingenuousness; she was concerned with status as well as power.

During George’s absences in Hanover she acted as regent on four occasions. With regal élan, she exercised patronage, commissioning architects and garden designers, providing financial assistance for poets, overseeing loose coteries of philosophers, scientists and divines; building for herself a splendid royal library adjoining St James’s Palace. She championed inoculation. The report she commissioned on a Parisian orphanage shaped Thomas Coram’s Foundling Hospital, opened after her death. She identified grounds for prison reform during the regency of 1732, but failed to persuade Robert Walpole to action. And from early in her marriage, aware that her husband’s destiny lay in Britain, she worked consistently at self-anglicisation, this German princess determined to succeed in the role of British queen. In scale her anglophile initiatives were large and small – from cultivating the good opinion of politicians and militarists to drinking tea and subscribing £100 to Pope’s translation of The Iliad. None of these acts was either wholly accidental or disjointed.

Caroline had inherited a Continental model of queenship. In German states, female consorts balanced the political and military governance of their husbands with spiritual and cultural direction. In Caroline’s case, innate ambition encouraged her to look beyond prescribed bounds: with variable success she took pains to dissimulate her aspirations. She blended affability with dignity but understood the importance, on occasion, of adopting what she called ‘grand ton de la reine’, full regal fig. As her unwavering support for her exacting spouse and her long association with Walpole show, she could be enthusiastic in partnership in order to achieve her ends. Others, like the letter-writing Lord Chesterfield and her husband’s mistress Henrietta Howard, would experience the vigour of her disapprobation.

That visible reminders of Caroline are scant in twenty-first-century Britain ought not to blind us to her achievements – or the scale of the obstacles she mostly overcame. Hers was a world in which the political was still personal, an elision she manipulated skilfully. Her overriding aim was that of every dynast: to ensure the survival of the precarious organisation she and her husband represented. In the early days, her personal popularity played its part in countering the threat to the Hanoverians of lingering Stuart support, a movement known as Jacobitism. More charismatic than her husband, more genuinely in thrall to her adopted country, she found admirers even among disaffected Catholics and Scots. There is a spin-doctor quality to aspects of her exploitation of soft power.

The present account seeks to offer some redress to Caroline of Ansbach’s historical vanishing act. Recent scholarship has re-examined George II’s conduct of monarchy to reveal a statesman more perceptive and engaged than earlier versions have suggested.18 Nor can Caroline be defined exclusively as the spirited, all-controlling heroine of Lord Hervey’s Memoirs, the ‘Goddess of Dulness’ satirised in Pope’s Dunciad, the scheming cynic who emerges from the letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu and Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, or the monstrous harridan imagined by the niece by marriage who never met her: ‘She was imperious, false, and ambitious. She has frequently been compared to Agrippina; like that empress, she might have exclaimed, let all perish, so I do but rule.’19 As the spectacular failure of her relationship with her eldest son indicates, Caroline had her share of flaws. She also inspired powerful affection, not least in her husband, whose devotion to her survived his long-term infidelity and the corrosive sycophancy of kingship.

Caroline worked hard at queenship. She was inspired by the examples of her guardian, Sophia Charlotte of Prussia, and her husband’s grandmother, Sophia of Hanover; eagerly she examined precedents established in Britain by recent queens-regnant Mary II and Queen Anne. Measured against the yardstick of her own devising, she enjoyed notable success at a time when the court still retained – in part, thanks to her – social, cultural and political significance. Although she was not single-handedly responsible for the successful establishment of the Hanoverians in Britain – or even in British affections – her understanding that she had a role to play in this process raises her above the average early-eighteenth-century princess. ‘Nothing will pass for what is great or illustrious, but what has true merit in it,’ wrote the unctuous Alured Clarke in An Essay Towards the Character of Her late Majesty Caroline, Queen-Consort of Great Britain, &c, published the year after Caroline’s death.20 We will see that Caroline’s life included its measure of merit.

Prologue

‘Halliballoo!’

Above the hubbub rose a single voice. On that dark December evening, the sound of a young woman singing soared above disarray. Above the noise of rain in nearby St James’s Park it lifted, above the dripping branches of lime trees planted in hundreds a decade ago by royal gardener Henry Wise.

Idlers heard it above the ‘racket of coxes! such a noise and halliballoo!’ in gaming dens and coffee houses.1 They heard it above the ‘Modern Midnight Conversation’ of boozy taverns shortly to be depicted by scourge of the age William Hogarth, above the ‘violent Fit[s] of Laughter’ in fashionable drawing rooms that novelist Sarah Fielding likened to ‘the Cackling of Geese, or the Gobbling of Turkeys’.2 Astringent as the sluice of ordure on wet cobbles, revoltingly inventoried by Jonathan Swift as ‘sweepings from butchers’ stalls, dung, guts, and blood,/Drowned puppies, stinking sprats, all drenched in mud,/Dead cats and turnip-tops’, her song trilled its defiant strain.3 Brightly, ‘despising doleful dumps’, it eclipsed the stamping hooves of horses, servants’ shuffling feet, hourly chimes from unlit churches.4 It rang clear above the clatter of packing cases, including the royal close stool entrusted to woman of the bedchamber Charlotte Clayton, above orders and counter orders and – unmistakeable in the broad London street – the sound of sobbing: ‘Over the Hills and Far Away’.

The Honourable Mary Bellenden was singing. Mary was a maid of honour, one of a group of high-spirited and decorative unmarried young women in attendance on Caroline, Princess of Wales. ‘The most perfect creature’, ‘smiling Mary, soft and fair as down’, ‘incontestably the most agreeable, the most insinuating, and the most likable woman of her time’, she was in flushed good looks tonight, singing in the shadows that skirted St James’s Palace.5 The same could not be said of her royal mistress. Two years previously, in one of his last excrescences as Poet Laureate, Nahum Tate had acclaimed flaxen-haired, inquisitive, plain-speaking Caroline as ‘adorned with every grace of person and of mind’.6 As the rank, wet December darkness enfolded princess and attendants in its clammy grip, she appeared anything but.

Loyal Mary sang for Caroline, an angry song of protest. ‘Over the Hills and Far Away’ was a rallying cry for Jacobites, those pro-Stuart opponents of Britain’s new Hanoverian monarchy; later, Mary Bellenden would be painted by portraitist Charles Jervas in the character of Mary, Queen of Scots. Caroline, of course, was herself a key player in the usurping dynasty. On 2 December 1717 she too played her part as victim.

Her father-in-law – for three years George I, elector of Hanover since 1698 and a man accustomed to obedience – had expelled her husband George Augustus from his rickety, brick-built palace following a footling argument about the choice of a royal godparent. In a satirical age, such septic dysfunctionalism was a boon to the writers of ballads and broadsheets. To the king’s chagrin, Caroline had chosen to accompany her husband into ignominy. ‘You may not only hope to live but Thrive, If with united hearts and hands you live,’ promised an engraving called ‘The Happy Marriage’, published in 1690, and throughout her marriage Caroline had done her best to present a united front.7 Surprised and displeased, the king shrugged his shoulders, comfortable in the apartments of his bald and red-faced German mistress overlooking the palace gardens. In the words of a ballad called ‘An Elegy upon the Young Prince’, ‘Both the Son and’s Spouse,/He left ’em no/Where else to go,/But turn’d ’em out on’s House’.8

No royal guards attended prince and princess in their hasty flit. The doors of the palace were closed against them, the Chapel Royal too, their attendance at court forbidden and every special act of deference suspended. Still the choleric and implacable monarch protested at his inability under British law to halt their payments from the civil list. Even Caroline’s children, a baby of three weeks and three daughters ranging in age from four to eight, were prevented from accompanying her in this hour of disgrace. They remained abed within the palace. The king had ‘[taken] his grey goose quill/And dip’t it o’er in gall’, a balladeer wrote. His sentence was comprehensive:

Take hence yourself, and eke your spouse,

Your maidens and your men,

Your trunks, and all your trumpery,

Except your children.9

Where the royal couple took their unhappy caravanserai was the house of Henry d’Auverquerque, Earl of Grantham. Since February, this slow-witted loyalist, his character dominated by ‘gluttony and idleness, … a good stomach and a bad head, … stupidity and ennui’, had served as Caroline’s lord chamberlain, the highest-ranking officer of her household.10

Up St James’s Street the convoy jolted. Across Piccadilly to Grantham House in Dover Street it wound its way. Servants followed separately, in the glimmering illumination of the new round glass street lamps, lit only on moonless nights, that marvelling visitors to the city likened to ‘little Suns of the Night’.11 The Duke of Portland described the party on arrival as ‘in the utmost grief and disorder, the Prince cried for two hours, and the Princess swooned several times’.12 Caroline had given birth only weeks earlier, an event, in the words of one phlegmatic diarist, ‘which occasioned great joy for the present, but proved of short duration’.13 Following months of escalating tension, the baby’s christening was the battleground on which king and prince collided. By 2 December neither Caroline’s strength nor her nerves had recovered from birth or baptism. Besides the daughters she entrusted to governesses on that darkest evening, she left behind her in the care of his wetnurse her baby son.

Caroline’s friend, the Countess of Bückeburg, recalled the anguish of their parting: ‘The poor Princess went into one faint after another when her weeping little Princesses said goodbye.’14 Caroline had told the king that she valued her children ‘not as a grain of sand compared to [her husband]’, but there was more of bravado than truth in the statement.15 None of the family would recover from the fissure wrought that winter night. Before the spring was out, the baby Caroline left behind her ‘kick’d up his heels and died’.16 He was killed by ‘convulsions’, water on the brain, a cyst on his tiny heart; each internal organ was swollen, distended, angrily inflamed. The miracle was that he had survived so long.17 That this looked bad for the king was cold comfort for a grief-stricken Caroline. ‘That which, in our more liberal age, would be considered as bare invective and scurrility, was the popular language of those times,’ wrote Lord Hailes, looking back in 1788.18 In this instance scurrility rose up in Caroline’s defence. Doggerel commended her suffering; it condemned the king’s heartlessness: ‘Let Baby cry/Or Lit [sic] it die/Own Mother’s Milk deny’d,/He no more car’d/How poor thing far’d.’19

‘Over the Hills and Far Away’ sang beautiful Mary Bellenden, and rain and darkness engulfed her song. The king she meant to upbraid was not listening, and the royal gaggle’s short journey, undertaken pell-mell on foot in view of a hastily convened sympathetic crowd, soon carried them out of earshot. In Lord Grantham’s house, smaller than their apartments in St James’s Palace, prince and princess were forced to share a bedroom. Such intimacy, and confines of space, prevented any ceremonial in their rising or retiring to bed, the complex rigmarole of bedchamber staff, of basins and ewers proffered on bended knee, shifts, chemises, gloves, fans and shoes presented or withdrawn by attendants greedy for the privilege: the ritualised posturing of baroque monarchy. Instead ‘Higgledy-piggledy they lay/And all went rantam scantam.’20