Полная версия

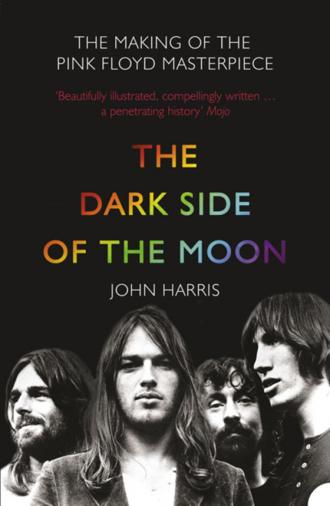

The Dark Side of the Moon: The Making of the Pink Floyd Masterpiece

JOHN HARRIS

THE DARK SIDE OF THE MOON

THE MAKING OF THE PINK FLOYD MASTERPIECE

Copyright

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

This edition published by Harper Perennial 2006

First published in Great Britain in 2005 by Fourth Estate

Copyright © John Harris 2005

John Harris asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780007232291

Ebook Edition © NOVEMBER 2012 ISBN 9780007383412

Version: 2016-03-18

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue January 2003

CHAPTER 1 The Lunatic Is in My Head: Syd Barrett and the Origins of Pink Floyd

CHAPTER 2 Hanging On in Quiet Desperation: Roger Waters and Pink Floyd Mark II

CHAPTER 3 And If the Band You’re in Starts Playing Different Tunes:The Dark Side of the Moon Is Born

CHAPTER 4 Forward, He Cried from the Rear: Into Abbey Road

CHAPTER 5 Balanced on the Biggest Wave: Dark Side, Phase Three

CHAPTER 6 And When at Last the Work Is Done: The Dark Side of the Moon Takes Off

Appendix Us and Them: Life After The Dark Side of the Moon

Keep Reading

Bibliography/Sources

Acknowledgements

Index

About the Author

About the Publisher

Dedication

For Hywel, who was right.

Prologue January 2003

‘I don’t miss Dave, to be honest with you,’ said Roger Waters, his voice crackling down a very temperamental transatlantic phone line. ‘Not at all. I don’t think we have enough in common for it to be worth either of our whiles to attempt to rekindle anything. But it would be good if one could conduct business with less enmity. Less enmity is always a good thing.’

He was speaking from Compass Point Studios, the unspeakably luxurious recording facility in the Bahamas whose guestbook was filled with the signatures of stars of a certain age and wealth bracket: the Rolling Stones, Paul McCartney, Eric Clapton, Joe Cocker. Waters was temporarily resident there to pass final judgement on the kind of invention with which that generation of musicians were becoming newly acquainted: a 5.1 surround-sound remix, one of those innovations whereby the music industry could persuade millions of people to once again buy records they already owned.

No matter that Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon had already been polished up to mark its twentieth anniversary in 1993; having been remixed afresh, it was about to be packaged up in newly designed artwork, and re-released yet again. Its ‘30th Anniversary SACD Edition’ would appear two months later, buoyed by an outpouring of nostalgia, and the quoting of statistics that had long been part of its authors’ legend.

The fact that they had the ring of cliché mattered little; Dark Side’s commercial achievements were still mind-boggling. In the three decades since it appeared, the album had amassed worldwide sales of around thirty million. In its first run on the US album charts, it clocked up no less than 724 weeks. In the band’s home country, it was estimated that one in five households owned a copy; in a global context, as Q magazine once claimed, with so many copies of Dark Side sold, it was ‘virtually impossible that a moment went by without it being played somewhere on the planet’.

That afternoon at Compass Point, Waters devoted a couple of hours to musing on the record’s creation, and its seemingly eternal afterlife. ‘I have a suspicion that part of the reason it’s still there is that successive generations of adolescents seem to want to go out and buy The Dark Side of the Moon at about the same time that the hormones start coursing around the veins and they start wanting to rebel against the status quo,’ he said. When asked what the record said to each crop of new converts, he scarcely missed a beat: ‘I think it says, “It’s OK to engage in the difficult task of discovering your own identity. And it’s OK to think things out for yourself.”’

As he explained, Dark Side had all kinds of themes: death, insanity, wealth, poverty, war, peace, and much more besides. The record was also streaked with elements of autobiography, alluding to Waters’s upbringing, the death of his father in World War II, and the fate that befell Syd Barrett, the sometime creative chief of Pink Floyd who had succumbed to mental illness and left his shell-shocked colleagues in 1968. What tied it all together, Waters said, was the idea that dysfunction, madness and conflict might be reduced when people rediscovered the one truly elemental characteristic they had in common: ‘the potential that human beings have for recognizing each other’s humanity and responding to it, with empathy rather than antipathy’.

In that context, there was no little irony about the terms in which he described the album’s place in Pink Floyd’s progress. In Waters’s view, the aforementioned statistics concealed the Faustian story of the band finally achieving their ambitions, and thus beginning the long process of their dissolution. ‘We clung together for many years after that – mainly through fear of what might lie beyond, and also a reluctance to kill the golden goose,’ he said. ‘But after that, there was never the same unity of purpose. It slowly became less and less pleasant to work with each other, and more and more of a vehicle for my ideas, and less and less to do with anyone else, so it became less and less tenable.’ In the words of Rick Wright, at the time Dark Side was created, ‘it felt like the whole band were working together. It was a creative time. We were all very open.’ Thereafter, Waters became so commanding that the possibility of any such joint endeavour was progressively closed down.

Naturally, you could hear some of this in the music. The band’s collective personality on Dark Side is warmly understated – a quality embodied in the gentle vocal blend of Wright and David Gilmour – and most of the sentiments expressed are intentionally universal: within the sea of personal pronouns in Waters’s lyrics, none occurs as often as ‘you’. From 1975’s Wish You Were Here onwards, however, Waters recurrently vented the very specific concerns of an increasingly troubled rock star. Underlining the change, as of Pink Floyd’s next album, 1977’s rather bilious Animals, Gilmour’s vocals were nudged to one side, while Waters’s unmistakable mewl became the band’s signature.

All this reached its conclusion on The Wall, the 1979 song-cycle-cum-grand-confessional-and-concert-spectacular that, in financial terms at least, achieved feats that even Dark Side hadn’t managed. Arguably the greatest achievement on Dark Side is ‘Us and Them’, a lament for the human race’s eternal tendency to divide itself into warring factions. By the time of this new project, which Waters still believes is of a piece with the band’s best work (‘I think The Wall is as good as The Dark Side of the Moon – I think those are the two great records we made together’), Pink Floyd’s music suggested one such example: Roger Waters versus the rest of the world.

Where Dark Side oozed a touching generosity of spirit, The Wall was bitterly misanthropic. Though the former combined its melancholy with hints of redemptive optimism, the latter seemed unremittingly bleak. And if the 1973 model of Pink Floyd had been a genuinely collective endeavour, by 1979, Gilmour, Wright and Nick Mason were very much supporting players (indeed, Wright had been sacked during The Wall sessions). All this reached a peak with 1983’s The Final Cut – according to its credits, ‘A requiem for the post-war dream by Roger Waters, performed by Pink Floyd.’ In its wake, Waters expressed the opinion that the band was ‘a spent force creatively’, announced his exit, and assumed that the story had drawn to a close. At least one account of this period claims that Waters’s parting shot to his colleagues was ‘You fuckers – you’ll never get it together.’

Much to Waters’s surprise – and against the backdrop of a great deal of legal tussling – Gilmour eventually decided to prolong the band’s life, creating his own de facto solo record, 1987’s A Momentary Lapse of Reason, and then enlisting Mason and Wright – the latter as a hired hand rather than an equal partner – for a world tour that found the group earning record-breaking receipts and settling into the life of a stadium attraction. In 1994, they released their second post-Waters album, The Division Bell, and commenced a vast world tour partly sponsored by Volkswagen. ‘I see no reason to apologize for wanting to make music and earn money,’ said Gilmour. ‘That’s what we do. We always were intent on achieving success and everything that goes with it.’

Waters, watching from afar, could not quite believe that Pink Floyd now denoted a group whose live presentations were built around an eight-piece band, and whose latest album featured songs credited to Gilmour and his wife, an English journalist and writer named Polly Samson. ‘I was slightly angry that they managed to get away with it,’ he said in 2004. ‘I was bemused and a bit disappointed that the Great Unwashed couldn’t tell the fucking difference … Well, actually they can. I’m being unkind. There are a huge number of people who can tell the difference, but there were also a large number of people who couldn’t. But when the second album came out … well, it had got totally Spinal Tap by then. Lyrics written by the new wife. Well, they were! I mean, give me a fucking break! Come on! And what a nerve: to call that Pink Floyd. It was an awful record.’

So it was that Gilmour and Waters had arrived at the impasse that defined their relations in the early twenty-first century. The upshot in 2003 was clear enough: a record partly based on the desirability of greater human understanding was being promoted by two men who had not spoken for at least fifteen years.

The week that Waters arrived at Compass Point, David Gilmour – long known to his friends and associates as Dave, before insisting on his full Christian name at some point during the 1990s – was at his home in Sussex, apparently embroiled in distanced negotiations with his old friend and colleague. ‘We’re in secondhand contact,’ he explained. ‘James Guthrie, our engineer, is remixing the album. Roger listens to it and I listen to it, and we both give our comments and have our little battles over how we think it should be through someone else. I’ve just had no contact with Roger since ‘87 or something. He doesn’t seem to want any. And that’s fine.’

Gilmour responded to questions about The Dark Side of the Moon with his customary reserve, couching a great deal of what he said in a businesslike kind of modesty. The record might have been elevated into the company of the nine or ten albums that go some way to defining what rock music is (or perhaps used to be): Highway 61 Revisited, Revolver, Pet Sounds, The Band, Led Zeppelin IV, et al. It undoubtedly continued to send thousands of listeners into absolute raptures. Yet at times, Gilmour still sounded surprised by what had happened. When asked about his memory of first appreciating the album in its entirety, he said this: ‘I don’t think any of us were in any doubt that we were moving in the right direction, and what we were getting to was something brilliant – and it was going to be more critically and commercially successful than anything we’d done before … I knew that we were moving up a gear, but no one can anticipate the sales and chart longevity of that nature.’

Every now and again, he could allow himself a laugh at the kind of absurdity that comes with such vast success. There was a gorgeous irony, for example, in the fact that Roger Waters had intended Dark Side’s lyrics to be unmistakably direct and simple, only to see all kinds of erroneous interpretations heaped on them – not least the absurd theory, circulated in the mid-1990s, that Dark Side had been created as a secret soundtrack to The Wizard of Oz. ‘I think Roger had got sick of people reading everything wrongly,’ said Gilmour. ‘He was always talking about demystifying ourselves in those days. And The Dark Side of the Moon was meant to do that. It was meant to be simple and direct. And when the letters started pouring in saying, “This means this, and this means that,” it was “Oh God.” But as the years go by, you realize that you’re stuck with it. And thirty years later you get The Wizard of Oz coming along to stun you. Someone once showed me how that worked, or didn’t work. How did I feel? Weary.’

As had become all but obligatory in his interviews, Gilmour also reflected on the creative chemistry that had once defined his relationship with Waters and fired the creation of Pink Floyd’s best music. ‘What we miss of Roger,’ he said in 1994, ‘is his drive, his focus, his lyrical brilliance – many things. But I don’t think any of us would say that music was one of the main ones … he’s not a great musician.’ Nine years on, he was sticking to much the same script: ‘I had a much better sense of musicality than he did. I could certainly sing in tune much better [laughs]. So it did work very well.’

Over in the Bahamas, Roger Waters had angrily pre-empted any such idea. ‘That’s crap,’ he said. ‘There’s no question that Dave needs a vehicle to bring out the best of his guitar playing. And he is a great guitar player. But the idea, which he’s tried to propagate over the years, that he’s somehow more musical than I am, is absolute fucking nonsense. It’s an absurd notion, but people seem quite happy to believe it.’

All that apart, and presumably to Waters’s continuing annoyance, Gilmour was still the effective custodian of the Pink Floyd brand name. His last performance under that banner had taken place on 29 October 1994, in the echo-laden surroundings of Earls Court arena; poetically – and in brazen denial of its chief architect’s continued absence – the show had been built around a rendition of The Dark Side of the Moon. Now, when asked about the prospects of any further Pink Floyd records or performances, he sounded jadedly noncommittal. ‘At the moment, it’s something so far down my list of priorities that I don’t really think about it. I don’t have a good answer for you on that. I would rather do an album myself at some point, and get on with other things for the time being. Would I rule it out? Mmmm. Not a hundred per cent. One never knows when one’s vanity is going to take one.’

In June 2005, there came news so unlikely as to seem downright surreal. After a period of estrangement lasting two decades, Roger Waters and David Gilmour announced that they would both participate in a Pink Floyd reunion at the London Live 8 concert. ‘Like most people, I want to do everything I can to persuade the G8 leaders to make huge commitments to the relief of poverty and increased aid to the third world,’ read a statement issued by Gilmour. ‘Any squabbles Roger and the band have had in the past are so petty in this context, and if re-forming for this concert will help focus attention then it’s got to be worthwhile.’

Waters, meanwhile, issued a communiqué that sounded a slightly more gonzo note than his reputation as one of rock music’s intellectual sophisticates might have suggested. ‘It’s great to be asked to help Bob [Geldof] raise public awareness on the issues of third world debt and poverty,’ he said. ‘The cynics will scoff – screw ’em! Also, to be given the opportunity to put the band back together, even if it’s only for a few numbers, is a big bonus.’ His return, however temporary, seemed to provide retrospective confirmation that the Pink Floyd who had authored A Momentary Lapse of Reason and The Division Bell had not been the genuine article, though the Gilmour statement came with a slightly different spin: ‘Roger Waters will join Pink Floyd to perform at Live 8’ ran the headline on the official Pink Floyd website.

The group’s performance at Hyde Park – ‘Breathe/Breathe Reprise’, ‘Money’, ‘Wish You Were Here’ and ‘Comfortably Numb’, delivered with a poise and understatement that only served to enhance the music’s impact – sent interest in the Floyd’s music sky-rocketing; according to the Independent, the day after Live 8 found sales of the career anthology Echoes rising by 1,343%. Talk of a lasting rapprochement, however, was quickly squashed (for all the show’s wonders, Gilmour said the experience was as awkward as ‘sleeping with your ex-wife’). For the time being, their creative history thus remains sealed, long since hardened by hindsight into a picture of peaks, troughs and qualified successes.

To take a few example at random, 1967’s The Piper at the Gates of Dawn is fondly loved by a devoted fan-cult, and couched in the semi-tragic terms of an artistic adventure that was ended far too soon. Ummagumma (1969) is treasured by only hardened disciples; Wish You Were Here often seems as worshipped as The Dark Side of the Moon. Animals and Meddle (1971) are the kind of records that those who position themselves a little higher than the average record-buyer habitually claim to be underrated and overlooked – and when The Wall enters any discussion, its champions often shout so passionately that any opposing view is all but drowned out.

By way of underlining Waters’s view of their history, the two albums that Gilmour piloted in his absence are rarely mentioned these days. The accepted view of their merits is that they represented ‘Floyd-lite’, an invention that worked very well as a means of announcing mega-grossing world tours, but hardly stood up to the band’s best work. That said, the idea that most of Pink Floyd’s brilliance chiefly resided in the mind of Roger Waters has been rather offset by the underwhelming solo career that began with 1984’s The Pros and Cons of Hitch Hiking – proof, despite the occasional glimmer of brilliance, that he too is destined to toil in the slipstream of the music he created in the 1970s.

The record with the most inescapable legacy is, of course, The Dark Side of the Moon – an album whose reputation is only bolstered by the fascinating story of its creation. Far from being created in the cosseted environs of the recording studio, it was a record that lived in the outside world long before it was put to tape: played, over six months, to audiences in American cities, English towns, European theatres, and Japanese arenas, while it was edited, augmented, and honed by a group who well knew they were on to something.

Perhaps most interestingly, it is a record populated by ghosts – most notably, that of Syd Barrett. In seeking to address the subject of madness, and question whether the alleged lunacy of particular individuals might be down to the warped mindset of the supposedly sane, Roger Waters was undoubtedly going back to one of the most traumatic chapters in Pink Floyd’s history – when their leader and chief songwriter, propelled by his prodigious drug intake, had split from a group who seemed to have very little chance of surviving his departure. For four years after Barrett’s exit, through such albums as A Saucerful of Secrets, Atom Heart Mother, and Meddle, they had never quite escaped his shadow; there is something particularly fascinating about the fact that the album that allowed them to finally break free was partly inspired by his fate.

All that aside, Dark Side is the setting for some compellingly brilliant music. There are few records that contain as many shiver-inducing elements: the instant at which the opening chaos of ‘Speak to Me’ suddenly snaps into the languorous calm of ‘Breathe’; just about every second of ‘The Great Gig in the Sky’ and ‘Us and Them’; the six minutes that begins with ‘Brain Damage’ and climaxes so spectacularly with ‘Eclipse’. Nor are there many examples of an album being defined by a central concept that would be so enduring. Other groups have come up with song-cycles based on ancient legend, the sunset of the British Empire, futuristic dystopias, and pinball-playing messiahs. Pink Floyd, to their eternal credit, opted to address themes that would, by definition, endure long after the record had been finished, and the band’s bond had dissolved.

That Dark Side hastened that process only adds to the story’s doomed romance. ‘With that record, Pink Floyd had fulfilled its dream,’ said Roger Waters, as the transatlantic static fizzed and he prepared to return to Dark Side’s new remix. ‘We’d kind of done it.’

Over in England, David Gilmour had voiced much the same sentiments; if only on that one subject, he and his estranged partner seemed to be united. ‘After that sort of success, you have to look at it all and consider what it means to you, and what you’re in it for: you hit that strange impasse where you’re really not very certain of anything any more. It’s so fantastic, but at the same time, you start thinking, “What on earth do we do now?”’

CHAPTER 1

The Lunatic Is in My Head

Syd Barrett and the Origins of Pink Floyd

On 22 July 1967, the four members of Pink Floyd were en route to the city of Aberdeen, the most northerly destination for most British musicians. The next night, they would call at Carlisle, where they would share the stage with two unpromisingly-named groups called the Lemon Line and the Cobwebs. Such was the life of a freshly successful British rock group in the mid-to-late 1960s: a seemingly endless trek around musty-smelling ballrooms, where the locals might be attracted by the promise of seeing the latest Hit Sensation, and musicians could be sure of being rewarded in cash. If London proved too far for a drive home, they and their associates would be billeted to a reliably dingy bed and breakfast.