Полная версия

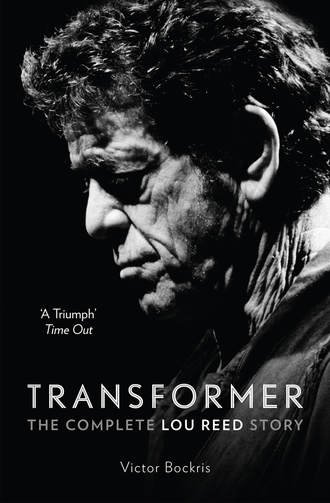

Transformer: The Complete Lou Reed Story

The area has a history of fostering comedians and a particular type of humor. Freeport in the twenties was a clam-digging town with an active Ku Klux Klan and German-American bund in nearby Lindenhurst. In the thirties and forties, it attracted a segment of the East Coast entertainment world, including many vaudeville talents. The vaudevillians brought with them not only their eccentric lifestyles and corny attitudes, but the town’s first blacks, who initially worked as their servants. By the time the Reeds got there, the show people were adding their own artistic bent to the town’s musical heritage. Their immediate neighbours included Leo Carrillo, who played Pancho on the popular TV show The Cisco Kid, as well as Xavier Cugat’s head marimba player and Lassie’s television mother, June Lockhart. Guylanders (Long Islanders) refuse to be impressed by celebrities, dignitaries, and the airs so dear to Manhattanites. “My main memory of Lou was that he had a tremendous sense of satire,” recalled high-school friend John Shebar. “He had a certain irreverence that was a little out of the ordinary. Mostly he would be making fun of the teacher or doing an impersonation of some ridiculous situation in school.”

Much Jewish humor took on a playfully cutting edge, intending to humble a victim in the eyes of God. Despite his modest temperament, Sidney Reed possessed a potent vein of Jewish humor, which he passed on to his son. As a child Lewis mastered the nuances of Yiddish humor, in which one is never allowed to laugh at a joke without being aware of the underlying sadness deriving from the evil inherent in human life. A family friend, recalling a visit to the Reed household, commented, “Lou’s father is a wonderful wit, very dry. He’s a match for Lou’s wit. That’s a Yiddish sense of humor, it’s very much a put-down humor. A Yiddish compliment is a smack, a backhand. It’s always got a little touch of mean. Like, you should never be too smart in front of God. Only God is perfect, and you should remember as pretty as you are that your head shouldn’t grow like an onion if you put it in the ground. You can either take it personally, like I think Lou unfortunately did, or not.”

During Lou’s childhood, Sidney Reed’s sense of humor had curious repercussions in the household. His well-aimed barbs often made his son feel put-down and his wife look stupid. Far from being resentful, Toby admired her husband for his obvious wit. Lou, however, was not so generous. “Lou’s mother thought she was dumb,” recalled a family friend. “I don’t think she was dumb. Lou thought she was dumb for thinking that his father was so clever. I think it was just jealousy. I think it was the boy who wanted all of his mother’s attention.” According to another friend, not only was Sidney Reed a wit, but he maintained a great rapport with Toby, who loved him dearly—much to the chagrin of the possessive, selfish, and often jealous Lewis. “I remember his mother was always amused by his father. His mother admires his father and thinks it’s too bad that Lou doesn’t see his father the way he is.”

One friend who accompanied Lou to school daily recalled that Toby Reed smothered her son with attention and concern. “I think his mother was fairly overbearing. Just in the way he talked about her. She was like a protective Jewish mother. She wanted him to get better grades and be a doctor.” Such attentions, of course, were fairly typical of full-time mothers in the family-oriented fifties. Allen Hyman never found her unusual. “I always thought Lewis’s mother was a very nice person,” he said. “She was very nice to me. I never viewed her as overbearing, but maybe he did. My experience of his parents was that they were very nice people. He might have perceived them as being different than they were. My mother and father knew his parents and my mother knew his mother. They were very involved parents. His mother was never anything but really nice. Whenever we went there, she was anxious to make sure we had food. His father was an accountant and seemed to be a particularly nice guy. But Lewis was always on the rebellious side, and I guess that the middle-class aspect of his life was something that he found disturbing. My experience of his relationship with his parents when we were growing up was that he was really close to them.

“His mother and father put up with a lot from him over the years, and they were always totally supportive. I got the impression that Mr. Reed was a shy man. He was certainly not Mr. Personality. When you went out with certain parents, it was fun and they were the life of the dinner and they bought you a nice meal, but when you went out with Sidney Reed, you paid. When you’re a kid, that’s unusual. The check would come and he’d say, ‘Now your share is …’ Which was weird. But that was his thing, he was an accountant.”

Lou’s father was very quiet; his mother had a lot more energy and a lot more personality. She was an attractive woman, always wore her hair short, had a lovely figure and dressed immaculately. “He’d always found the idea of copulation distasteful, especially when applied to his own origins,” Lou wrote in the first sentence of the first short story he ever published. The untitled one-page piece, signed Luis Reed, was featured in a magazine, Lonely Woman Quarterly, that Lou edited at Syracuse University in 1962. It hit on all the dysfunctional-family themes that would run through his life and work.

His quixotic/demonic relationship to sex was clearly intense. Lou either sat at the feet of his lovers or devised ingenious ways to crush their souls. The psychology of gender was everything. No one understood Lou’s ability to make those close to him feel terrible better than the special targets of his inner rage, his parents, Sidney and Toby. Lou dramatized what was in 1950s suburban America his father’s benevolent dominance into Machiavellian tyranny, and viewed his mother as the victim when this was not the case at all. Friends and family were shocked by Lou’s stories and songs about intra-family violence and incest, claiming that nothing could have been further from the truth. In the story, Lou had his mother say, “Daddy hurt Mommy last night,” and climaxed with a scene in which she seduced “Mommy’s little man.” Lou would later write in “How Do You Speak to an Angel” of the curse of a “harridan mother, a weak simpering father, filial love and incest.” The fact is that Sidney and Toby Reed adored and enjoyed each other. After twenty years of marriage, they were still crazy about each other. As for violence, the only thing that could possibly have angered Sidney Reed was his son’s meanness to his wife. However, these oedipal fantasies revealed a turbulent interior life and profound reaction to the love/hate workings of the family.

In his late thirties, Lou wrote a series of songs about his family. In one he said that he originally wanted to grow up like his “old man,” but got sick of his bullying and claimed that when his father beat his mother, it made him so angry he almost choked. The song climaxed with a scene in which his father told him to act like a man. He did not, he concluded in another song, want to grow up like his “old man.”

Reed’s moodiness was but one indication that he was developing a vivid interior world. “By junior year in high school, he was always experimenting with his writing,” Hyman reported. “He had notebooks filled with poems and short stories, and they were always on the dark side.” Reed and his friends were also drawn to athletics. Freeport High was a football school. Under the superlative coaching of Bill Ashley, the Freeport High Red Devils were the pride of the town. Lou would claim in Coney Island Baby that he wanted to play football for the coach, “the straightest dude I ever knew.” But he had neither the size nor the athletic ability and never even tried out. Instead, during his junior year Lou joined the varsity track team. He was a good runner and was strong enough to become a pole-vaulter. (He would later comment on Take No Prisoners that he could only vault six feet eight inches—“a pathetic show.”) Although he preferred individual events to team sports, he was known around Freeport as a very good basketball player. “Lou Reed was not only funny but he was a good athlete,” recalled Hyman. “He was always kind of thin and lanky. There was a park right near our house and we used to go down and play basketball. He was very competitive and driven in most things he did. He would like to do something that didn’t involve a team or require anybody else. And he was exceptionally moody all the time.”

Allen’s brother Andy recalled that it was typical of Lou to maintain a number of mutually exclusive friendships, which served different purposes. Allen was Lewis’s conservative friend, while his friend and neighbor Eddie allowed him to exercise quite a different aspect of his personality. “Eddie was a real wacko,” commented another high-school friend, Carol Wood, “and he only lived about four houses away from Lou. He had all these weird ideas about outer-space Martians landing and this and that. During that time there was also a group in town that was robbing houses. They were called the Malefactors. It turned out that Eddie was one of them.”

“Eddie was friendly with Lou and with me, but Eddie was a lunatic,” agreed Allen Hyman. “He was the first certifiable person I have ever known. He was one of those kids who your mother would never want or allow you to hang out with because he was always getting into trouble. He had a BB gun and he would sit up in his attic and shoot people walking down the street. Lou loved him because he was as outrageous as he was, maybe more. He used to get arrested, he was insane.”

“There was a desire on Lewis’s part—of course I didn’t know this at the time—to be accepted by the regular kinds of guys, and on the other hand he was very attracted to the degenerates,” Andy recalled. “Eddie was kind of a crazy guy who was into petty theft, smoking dope at a very early age, and into all kinds of strange stuff with girls. And Lewis was into all that kind of stuff with Eddie while he was involved with my brother in another scene.” Having managed to convince his parents to buy him a motorcycle, Lou would ride around the streets of Freeport in imitation of Marlon Brando.

Where Lou spent his troubled teen years in Freeport. (Victor Bockris)

According to his own testimony, what made Lewis different from the all-American boys in Freeport was the fact, discovered at the age of thirteen, that he was homosexual. As he explained in a 1979 interview, the recognition of his attraction to his own sex came early, as did attempts at subterfuge: “I resent it. It was a very big drag. From age thirteen on I could have been having a ball and not even thought about this shit. What a waste of time. If the forbidden thing is love, then you spend most of your time playing with hate. Who needs that? I feel I was gypped.”

“There was no indication of homosexuality except in his writing,” said Hyman. “Towards our senior year some of his stories and poems were starting to focus on the gay world. Sort of a fascination with the gay world, there was a lot of that imagery in his poems. And I just thought of it as his bizarre side. I would say to him, ‘What is this about, why are you writing about this?’ He would say, ‘It’s interesting. I find it interesting.’”

“I always thought that the one way kids had of getting back at their parents was to do this gender business,” recalled Lou. “It was only kids trying to be outrageous. That’s a lot of what rock and roll is about to some people: listening to something your parents don’t like, dressing the way your parents won’t like.”

Throughout his adolescence, Lou was saved by his real passion, rock and roll. Lou had fallen for the new R&B sounds in 1954, when he was twelve. Almost instantly, he had started composing songs of his own. Like his fellow teenager Paul Simon, who grew up in nearby Queens, Lou formed a band and put out a single of his own composition at the age of fifteen, appropriately called “So Blue.” To Lou’s parents, these early signposts of a musical career were ominous. Their dreams of having their only son become a doctor or, like his father, an accountant were vanishing in the haze of pounding music and tempestuous moods. Since puberty Lou had honed a sharp edge, wounding his parents with both public and private insults. In his teens, Lou led Mr. and Mrs. Reed to believe he would become both a rock-and-roll musician and a homosexual—the stuff of nightmares for suburban parents of the 1950s. Actively dating girls at the time, and giving his friends every impression of being heterosexual, Lou enjoyed the shock and worry that gripped his parents at the thought of having a homosexual son. “His mother was very upset,” recalled a friend. “She couldn’t understand why he hated them so much, where that anger came from. At first, they had no malice, they tried to understand. But they got fed up with him.”

Reed playing in one of his highschool bands, the C.H.D. or, backwards, Dry Hump Club.

Throughout his teens, Lou would try anything to break the tedium of life in Freeport, especially if it was considered outside conventional norms. Lou found other characters who were also desperate to elude boredom. One such moment came about indirectly through his interest in music. Every evening, the better part of the high-school population of Freeport and its neighboring towns would tune into WGBB radio to hear the latest sounds, make requests, and dedicate songs. Often the volume of telephone calls to the station would be so great that the wires would get crossed, creating a teenage party-line over which friendships developed. On one occasion, Lou became friendly with a caller. “There was this girl who lived in Merrick,” explained Allen Hyman. “She was fairly advanced for her time, and Lou ended up going out on a date with her. He came back from the date, and he called me up and he said, ‘I’ve just had the most amazing experience. I took this girl to the Valley Stream drive-in and she took out a reefer.’ And I said, ‘Is she addicted to marijuana?’ Because in those days we thought if you smoked marijuana, you were an addict. He said, ‘No, it was cool. I smoked this reefer, it was really great.’”

The decades in which Lewis grew up, the fifties and early sixties, were characterized by middle-class unconsciousness and safety. Much like in the TV series Happy Days, most teenagers were more interested in having a good time than experiencing a wider worldview. “There was not a tremendous amount of consciousness about what was happening on the planet,” commented Allen Hyman. “But Lou was always interested in questioning authority, being a little outrageous, and he was certainly a person who would be characterized as mildly eccentric.”

Lou’s eccentric rebellious side found a lot to gripe about within the conservative, white confines of his neighborhood. Hyman remembered that, though outwardly polite, Lou harbored a hatred of his environment that was manifested in an ill will for Allen’s right-wing father. “The reason he disliked my father so much was because he always viewed him as the consummate Republican lawyer. He was very aware early on of political differences in people. We lived in an area that was Republican and conservative, and he always rebelled against that. I couldn’t understand why that upset him so much. But he was always very respectful to my parents.”

Mr. Reed, along with Mr. Hyman, discouraged musical careers for their sons. “He thought there were bad people involved, which there were,” recalled Lou. However, as Richard Aquila wrote in That Old Time Rock and Roll, “adult fear of rock and roll probably says more about the paranoia and insecurity of American society in the 1950s and early 1960s than it does about rock and roll. The same adults who feared foreigners because of the expanding Cold War, and who saw the Rosenbergs and Alger Hiss as evidence of internal subversion, often viewed rock and roll as a foreign music with its own sinister potential for corrupting American society.”

Lewis enjoyed the comforts of his middle-class upbringing, but acted as if he were estranged from the dominant values of suburban American life. Lou would rewrite his childhood repeatedly in an attempt to define himself. Some of his most famous songs, written in reaction to his parents’ values, have a stark, despairing tone that spoke for millions of children who grew up in the stunned and silent fifties of America’s postwar affluence. One friend put her finger on the pulse of the problem when she pointed out that Lou had an extreme case of shpilkes—a Yiddish term that perfectly sums up his contradictory nature: “A person with shpilkes has to scratch not only his own itch, he can’t leave any situation alone or any scab unpicked. If the teenage Lewis had come into your home, you would have said, ‘My God, he’s got shpilkes!’ Because he’s cute and he’s warm and he’s lovable, but get him out of here because he’s knocking the shit out of everything and I don’t dare turn my back on him. He’s causing trouble, he’s aggravating me, he’s a pain in the ass!” According to Lou, he never felt good about his parents. “I went to great lengths to escape the whole thing,” he said when he was forty years old. “I couldn’t relate to it then and I can’t now.” As he saw himself in one of his favorite poems by Delmore Schwartz: “… he sat there / Upon the windowseat in his tenth year / Sad separate and desperate all afternoon, / Alone, with loaded eyes …”

Another charge Lou would lob at his unprotected parents was that they were filthy rich. This was, however, purely an invention Lou used to dramatize his situation. During Lou’s childhood his father made a modest salary by American standards. The kitchen-table family possessed a single automobile and lived in a simply though tastefully furnished house with no vestiges of luxury or loosely spent funds. Indeed, by the end of the 1950s, what with the shock treatments, Lou’s college tuition, and their daughter Elizabeth’s coming into her teens, the Reeds were stretched about as far as they could reach.

***

The year of his electroshock treatments, 1959, through the summer of 1960 was a lost time for Lou. From then on, the central theme of his life became a struggle to express himself and get what he wanted. The first step was to remove himself from the control of his family, which he now saw as an agent of punishment and confinement. “I came from this small town out on Long Island,” he stated. “Nowhere. I mean nowhere. The most boring place on earth. The only good thing about it was you knew you were going to get out of there.” In August he registered and published a song called “You’ll Never, Never Love Me.” A gut resentment of his parents was blatantly expressed in another song, “Kill Your Sons.” The music, he later said, gave him back his heartbeat so he could dream again. “The music is all,” he wrote in a wonderful piece of prose called “From the Bandstand.” “People should die for it. People are dying for everything else, so why not for the music. It saves more lives.”

Chapter Two

Pushing the Edge

SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY: 1960–62

Lou liked to play with people, tease them and push them to an edge. But if you crossed a certain line with Lou, he’d cut you right out of his life.

Allen Hyman

In order to continue their friendship, Lou and Allen Hyman had conspired to attend the same university. “In my senior year in high school Lou and I and his father drove up to Syracuse for an interview,” recalled Allen. “We didn’t speak to his father much, he was quiet. Quiet in the sense of being formal—Mr. Reed. We stayed at the Hotel Syracuse, which was then a real old hotel. There were also a bunch of other kids who were up for that with their parents. Would-be applicants to Syracuse. Lou’s father took one room and Lou and I took another. We met a bunch of kids in the hall that were going to Syracuse and we had this all-night party with these girls we met. We thought this was going to be a gas, this is terrific. The following day we both knew people who were going to Syracuse at the time who were in fraternities, and the campus was so nice, I think it was the summer, it was warm at the time, it looked so nice.”

The two boys made an agreement that if they were both accepted, they would matriculate at Syracuse. “We both got in,” said Hyman. “And the minute I got my acceptance I let them know I was going to go and I called Lou very excited and said, “I got my acceptance to Syracuse, did you?” And he said, ‘Yes.’ So I said, ‘Are you going?’ and he said, ‘No.’ And I said, ‘What do you mean, no? I thought we were going, we had an agreement.’ He said, ‘I got accepted to NYU and that’s where I’m going.’ I said, ‘Why would you want to do that, we had such a good time up there, we liked the place, I told them I was going, I thought you were going.’ He said, ‘No, I got accepted at NYU uptown and I’m going.’”

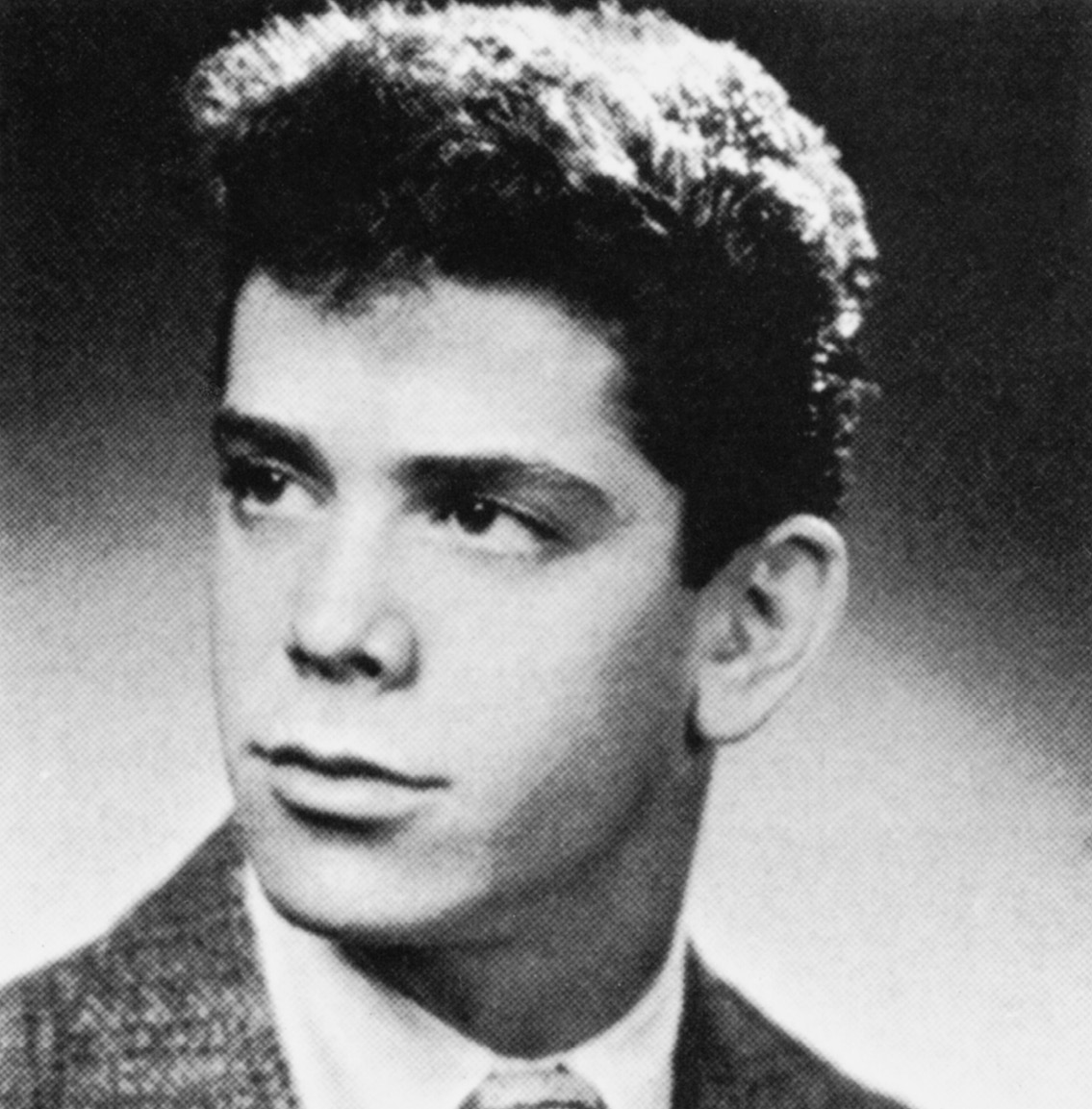

Lewis Reed, 17, 1959. ‘I don’t have a personality.’

In the fall of 1959, Lou headed off to college. Located in New York City, New York University seemed like a smart choice for a man who loved nothing more than listening to jazz at the Five Spot, the Vanguard, and other Greenwich Village clubs. But the Village was not the NYU campus Lou chose. Almost incomprehensibly, he signed up for the school’s branch located way uptown in the Bronx. NYU uptown provided Reed with neither the opportunities nor the support that he needed. Instead, Lou was left floundering in a strange and hostile environment. One of his few pleasures came from visiting the mecca of modern jazz, the Five Spot, regularly, but he didn’t always have the money to get in and often stood outside listening to Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, and Ornette Coleman as the music drifted out to the street.

However, Lou’s main concern was not college. The Bronx campus was convenient to the Payne Whitney psychiatric clinic on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, where he was undergoing an intensive course of postshock treatments. According to Hyman, who talked to him on the phone at least once a week through the semester, Lou was having a very, very bad time. “He was in therapy three or four times a week,” Hyman recalled. “He hated NYU. He really hated it. He was going through a very difficult time and he was taking medication. He was having a lot of difficulty dealing with college and day-to-day business. He was a mess. He was going through a lot of very, very bad emotional stuff at the time and he probably had something very close to a minor breakdown.”

After two semesters, in the spring of 1960, having completed the Payne Whitney sessions although still on tranquilizers, Lou couldn’t take the NYU scene anymore.

One of the few people who encouraged Lou during his yearlong depression was his stalwart childhood friend, Allen Hyman, who now urged him to get away from his parents. Allen encouraged Lou to join him at Syracuse—a large, prestigious, private university, hundreds of miles from Freeport. In the fall of 1960, shaking off the shadows of Creedmore and the medication of Payne Whitney, Reed took Hyman’s advice and enrolled at Syracuse.

***

The coeducational university, attended by some nineteen thousand sciences and humanities students, had been established in 1870. It was located on a 640-acre campus atop a hill, in the middle of the city. Its $800 per term tuition was relatively high for a private university. Most of the students lived in sororities and fraternities and were enjoying one last four-year party before putting aside childish notions for the economic responsibilities of adulthood. There was, among the student population, a large and wealthy Jewish contingent, generally straight-arrow fraternity men and sorority women bound for careers in medicine and law. There was a small margin of artists, writers, and musicians with whom Lou would throw in his lot, enjoying, for the first time in his life, a niche in which he could find a degree of comfort. Among many other talented and successful people, the artist Jim Dine, the fashion designer Betsey Johnson, and the film producer Peter Guber all graduated in Reed’s class of 1964.