Полная версия

The Big House: The Story of a Country House and its Family

Parson did not recover from his illness, and his death the following year solved Christopher’s housing problem. He survived long enough, however, to be the beneficiary of a great honour bestowed upon him by the King. Writing to Christopher early in February, 1783, Richard Beaumont, his friend and fellow plantsman, told him that he had heard ‘that a Baronet will shortly be created in the East Riding, so saith a Friend connected with the Rulers of the Nation’.4 The Baronetcy to which he referred was to be offered to Christopher as a reward for his contribution to the reclamation of the Wolds. The high esteem in which he held his father is evident from the fact that he chose to turn down the title, insisting that it was conferred upon Parson instead. On 25 February, 1783, the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, the Rt Hon. Thomas Townshend, signed a patent on behalf of King George III: ‘Our will & pleasure is that you prepare a Bill for our Royal Signature to pass our Great Seal containing the Grant of the Dignity of a Baronet of this our Kingdom of Great Britain unto our trusty and well beloved Mark Sykes, Doctor in Divinity, of Sledmire in our County of York.’5 So Parson became the Revd Sir Mark Sykes, 1st Baronet of Sledmere.

Amongst the hundreds of letters of congratulation that came pouring in for both the new Baronet and his son was one from Uncle Joseph, who lamented that ‘his poor state of Health will afford him so little enjoyment of this or of almost any earthly Comfort’.6 They were prophetic words. On 9 September Christopher recorded in his diary, ‘My father taken ill’, and the following Sunday, 14 September, ‘My Dear Father died at 4½ this morning. I got to Sledmere at 8½ not knowing of his illness till the night time at Hull Bank.’ He was buried on 19 September. ‘The Remains of my Dear Father,’ noted Christopher, ‘was taken from Sledmere at 8½ o’clock and was buried at Roos at 6 o’clock in the evening.’7 His coffin was attended only by his servants, a stipulation he had made in his will. ‘The very painful & lingering life which My Uncle led,’ wrote Parson’s nephew, Nicholas, to Christopher, ‘may make his death be looked upon as a happy release by all his Friends.’8

By the end of 1783, Christopher, Bessy and the five children had moved into the big house, unfortunately for them in the middle of an exceptionally cold winter. In an age when most of us live in over-heated houses, it is easy to forget how uncomfortable it must have been to live in a large draughty house in periods of harsh and freezing weather. It was still a number of years before the advent of any kind of central heating, and the inhabitants had to rely on individual fires as their only source of warmth. ‘I hope you all keep well & have plenty of Coals,’ wrote Henry Maister to Christopher in January, 1784, ‘for around a good fire is the only comfortable place’,9 though the truth is that most fireplaces usually produced more smoke than heat, and the only guaranteed way to keep warm was to wear more clothes. On 3 January, Christopher recorded ‘a heavy storm of snow’ in his diary, and throughout January and February there are regular entries for ‘deep snow’ and sometimes ‘extremely deep snow’. Things finally began to improve on 22 February, when Christopher was able to write ‘began this day to thaw’.10

No doubt inspired by the Arctic conditions they had been experiencing, Christopher also set about a new piece of building work at Sledmere, the creation of an ice-house. These buildings, which were de rigueur in most big houses of the day, were an advanced version of a ‘snow-well’ built for the Duke of York at St James’s Palace in 1666. While that had been little more than a pit dug into the ground and thatched with straw, the new models were often architect-designed and vaulted in brick or stone.11 They were situated close to the nearest large stretch of water – in the case of Sledmere, it would have been the Mere – so that during the winter the ice could be cut and placed in the ice-house, carefully insulated between layers of straw, for use the following summer, when it would have been used primarily for the refrigeration of food as well as for the occasional iced dessert. The design for the Sledmere ice-house came in the form of a working drawing, showing a detailed and carefully labelled section, sent to Christopher in February, 1784 by John Carr, the architect of Castle Farm. It was dug out in July and a sum of 12s. 6d. was entered in the house accounts the following January for ‘filling Ice-House’.

Seventeen eighty-four may well have been a momentous year for Christopher and his family, their feet firmly perched upon the ladder of social ascendancy, but so it was for the outside world too. There was change in the air. The disastrous War of American Independence was over, and the ministry of the man who had presided over it, Lord North, had disintegrated. A new group of radical thinkers was beginning to influence politics, men like Joseph Priestley, Richard Price, Erasmus Darwin and Benjamin Franklin, who believed in the reformation of Parliament and in John Dunning’s famous motion ‘that the power of the Crown has increased, is increasing, and ought to be diminished’. They had found a voice in the short-lived Parliament of Lord Rockingham’s Whig Party and had achieved a number of reforms before his sudden death in July, 1782, including the reorganisation and reduction of the Royal household, the disenfranchisement of revenue officers, and the debarring of government contractors from sitting as MPs.

The short reign of Rockingham’s successor, Lord Shelburne, and the speedy collapse of the ministry which followed – an ill-judged coalition of two implacable enemies, the unpopular Lord North and the Whig, Charles James Fox – allowed King George III to invite a rising young star, William Pitt, to form a Government. Pitt, the second son of the Earl of Chatham, himself Prime Minister over a period of twelve years, made his maiden speech at the age of twenty-one, served in Lord Shelburne’s Cabinet as Chancellor of the Exchequer aged twenty-three, and was only twenty-four when he became First Minister. Though this might seem an extraordinary feat to most people, it would not have surprised his family, whose nicknames for him – ‘William the Great’, when he was a small child, and ‘the Young Senator’, ‘the Orator’ and ‘the Philosopher’ when he was in his teens – suggest that they had a strong hunch he would go far.12 When aged only seven, his mother had written to her husband, ‘of William, I said nothing, but that was because he cannot be extraordinary for him’.13

Pitt was in the right place at the right time when oratory was becoming more and more a feature of debate. His maiden speech, made on 26 February, 1781, caused the assembled members to prick up their ears, especially since it was made off the cuff as a result of an unexpected call by a number of the opposition, eager to test out the so-called brilliance of Chatham’s son. They were not disappointed. ‘It impressed … from the judgment, the diction and the solemnity that pervaded and characterised it,’ wrote Nathaniel Wraxall, who was present. ‘The statesman, not the student, or the advocate, or the candidate for popular applause, characterised it … All men beheld in him at once a future Minister, and the members of the Opposition, overjoyed at such an accession of strength, vied with each other in their encomiums as well as in their predictions of his certain political elevation.’14 Indeed Edmund Burke was so overcome with admiration that he is reported as having said ‘he is not merely a chip off the old block, but the old block itself’.15

It was not long before Pitt had the ears of the House whenever he spoke, an honour rarely granted to new young members, and his name soon began to be known to a wider public beyond the benches of the Commons. As early as February, 1783, when he was still only twenty-three, he was the choice of a number of astute politicians to succeed Shelburne, who had resigned after two Government defeats. ‘There is scarcely any other Political Character of consideration in the Country,’ wrote Henry Dundas, ‘to whom many people from Habits, from Connections, from former Professions, from Rivalships and from Antipathies will not have objections. But he is perfectly new ground …’16 He actually was sent for by the King, but turned down the offer, on the grounds that if he was to come to power it was to be on his own terms. It was a brave and shrewd decision, for when the King asked him a second time the following December and he accepted, he was in an unassailable position. The news was received in the House of Commons with a shout of laughter. It was, after all,

A sight to make surrounding nations stare; A Kingdom trusted to a school-boy’s care.17

Any ambitious young man of position would have been swept up in the excitement of the moment, and in the general election of March, 1784 that put Pitt into office, a notorious affair that had gone on for forty days – ‘forty days’ poll, forty days’ riot and forty days’ confusion’ as Pitt himself put it18 – Christopher stood as MP for Beverley. His election was by no means a foregone conclusion since the rival candidate, Sir James Pennyman, had an enthusiastic following. ‘Sir James came yesterday’ wrote John Hopper, ‘… they all cry Sir James for ever as usual, and the Bells Ringing with Every Demonstration of Joy at seeing him’.19 It is a measure of Christopher’s own popularity that he was returned with a majority of thirty-three, inspiring a local poet, John Bayley of Middleton, to come up with a suitably unctuous set of lines:

Whilst through the Streets loud Acclamations rung,

And Sykes’s Praises dwelt on every Tongue,

‘Twas you whose Merits influenced each Voice,

Unanimous to make so wise a choice.20

‘I … heartily congratulate you on your Success,’ wrote Henry Maister, ‘ ’tho I lament the furor of the times which call’d you forth, & only hope you may have no cause to regret the necessity of attending the House which I am sure will not agree with your Constitution, if the Hours in future are too as late as heretofore.’21 He was sworn in on 20 May, and in the early summer he was summoned to Downing Street – ‘14 at table’ he noted in his diary – where Pitt expressed his gratitude both to him and to his fellow MP, William Wilberforce, for the success of the important Yorkshire vote. Ironically it was the defeated Fox who had said in the past ‘Yorkshire and Middlesex between them make up all England.’22

While Christopher voted, there were the first stirrings at Sledmere of a move to improve the old house. On 29 June, 1784, ‘Lady S. laid foundation stone of offices in Court Yard,’23 noted Christopher in his diary. The work in question was the enlargement and modernisation of the probably rather cramped domestic offices at the north side of the house. The work was especially important as, according to a letter written in September, 1784 by a Miss JC to her sister Nancy, Mrs Marriott, Christopher and Bessy were already entertaining. She attended a small family party, consisting of the Sykeses and their five children, Mr and Mrs Egerton, Bessy’s brother and sister-in-law, and Richard Beaumont, Christopher’s West Yorkshire neighbour, whom she described as a ‘pretty little upright Man of Brazen Nose with a great deal of Linnen about his Neck … a strange being indeed.’ ‘I thought to captivate him,’ she added, ‘but he does not suit my taste.’

JC stayed the better part of a fortnight, and her letter gives a hint of what the atmosphere of the old house was like. ‘ ’Tis now a very good one of its Age,’ she wrote, ‘& reminds me of the Highgate House below stairs – here’s plenty of Books, Pictures good & Antiques, which keep one in constant amusement, besides Organ, Harpsichord, etc. etc.; which strange to tell I’ve exercised my small skill upon, before all the Party every day.’ Though she said she had been ‘taught to dread these Wolds’, she found herself ‘highly delighted & well may; nothing can be finer than the pure air here, only eighteen miles from Bridlington, the beautiful hill & dale of the country makes charming rides etc. Sir C has form’d & is forming great designs in the planting way which will beautify it prodigiously.’ She also confirmed that ‘the house is to be transformed some time’. Of her hosts she wrote, ‘Sir C & Ly Sykes are both extremely obliging, indeed I don’t know in what Family so nearly strangers to me, I cd. have been so agreeably placed for a visit … & not tire of it I assure you. Lady Sykes is very kind yet you must not expect any great polish in her, a resident in the country always, and without Education suitable to her great Fortune but she’ll improve in Londres.’24 She had, she added, ‘very weak nerves’, and ‘dreads being presented at Court, w’ch you can pity her for: but the family must be elevated’.25

Now that her husband was in politics, presentation at Court was something that Bessy could not avoid, since the wife of an MP could not go out in Society or attend any Court functions unless she had been presented and Christopher wanted to be seen. He bought himself a smart London house, paying £3,700, the equivalent today of £185,000, for 9 Weymouth St, just south of Regent’s Park and his diary for 1785 proudly opens with the words ‘Sir Chris Sykes Bart. MP Weymouth St.’ In accordance with his new status, he also bought himself a smart new coach, and had his coat of arms emblazoned on the doors. On 16 February, this gleaming new vehicle took the proud new member for Beverley and his beautiful wife to St James’s Palace for the ceremony she so dreaded.

Any woman of a nervous disposition could be forgiven for feeling anxious about the approaching ritual, in spite of the fact that she would have been preparing for it for weeks. ‘You would never believe,’ wrote Fanny Burney, Assistant Keeper of the Wardrobe to Queen Charlotte, to her sister-in-law, ‘the many things to be studied for appearing with a proper propriety before crowned heads.’ She then gave a barely ironic list of ‘directions for coughing, sneezing, or moving, before the King and Queen’, none of which were permitted, finishing with the observation that ‘if, by chance, a black pin runs into your head, you must not take it out … If, however, the agony is very great, you may, privately, bite the inside of your cheek, or of your lips, for a little relief; taking care to do it so cautiously as to make no apparent dent outwardly.’26

There would have been endless fittings for Bessy’s presentation gown, which was hoop-skirted and elaborate and had to be worn with a train, as well as many expeditions out to buy the accessories required to wear with it, such as slippers, a fan, ostrich feathers and jewellery. Then she was forced to endure hours of deportment training so that she could approach the Sovereign elegantly, curtsy in a single flowing movement, without losing her balance or tripping on her gown, and then – the most nerve-racking part of the whole business – walk backwards out of the room, gathering up her train as she went, striving her utmost not to fall over it. Such practice was often carried out using a tablecloth as a simulated train. Bessy’s presentation went without a hitch, and after it she patiently remained in London for three months while Christopher attended Parliament.

He soon had his first opportunity to prove his loyalty to the Prime Minister. Ever since he had first entered Parliament in 1781 Pitt had been a passionate advocate of parliamentary reform, believing that it was vitally necessary for the preservation of liberty. Amongst plans he had proposed were the checking of bribery at elections, the disenfranchising of corrupt constituencies, and the shortening of the duration of Parliament. On 18 April, 1785, he proposed a Bill that would extinguish thirty-six rotten boroughs and transfer the seventy-two seats therein to the larger counties and to London and Westminster. The House was full, with 450 members present, of which 422 voted in the division. Christopher and his fellow Yorkshiremen, the gentlemen and freeholders of a great county, were a powerful lobby and voted to a man with the Prime Minister, but he was defeated by 248 votes to 174. Memories were short. The movement for reform had been born in a time of crisis, now over, and with a recovery in trade and a resurgence of confidence, the issue was no longer a live one. Pitt’s success in other areas had virtually killed it off and he did not try again. Perhaps Christopher became dejected by Pitt’s unwillingness to pursue further the subject of parliamentary reform, but in the six years he represented Beverley he never once spoke in the House. More likely is the possibility that his heart was never really in politics at all, being firmly ensconced at Sledmere.

On 30 May 1785, the day he and Bessy returned to Yorkshire after his first vote in the House, Christopher was one week into his thirty-sixth year, and a very rich man. His landed income alone for that year was the equivalent of over £300,000 at today’s values, and he had a corresponding sum in the bank of well over £4,000,000. It was money he was to put to good use in carrying out his ambitious plans. His first task in the preparation of the landscape he envisaged round the house was to clear away any buildings standing within its sightlines. These consisted of the few houses that remained from the old village, whose street had run in front of the house. Levelling work began in the summer of 1785 and continued over the next year. The inhabitants, who had no choice in the matter, were moved to new cottages, which had already been built elsewhere.

At the same time he was also planning a walled garden, a design for which he drew on the survey that had been commissioned by his Uncle Richard back in 1755. It was positioned to the east of that part of the old Avenue which was closest to the house, and was designed as an octagon, with tall brick walls enclosing it and hot houses against the north walls. The attention to detail in this design was typical of everything that Christopher did. Each door, for example, had its own reference identifying what type of lock it was to have and who should have a key, namely ‘Labourer, Gardiner, and Master’. His final flourish was the design of a magnificent Orangery, nine bays in length with a semi-domed roof, sited immediately to the south-east of the house, between it and the walled garden. Though the Orangery has long since been demolished and the old wood-framed hothouses have been replaced by modern ones, this garden still survives, its beautiful brick walls, pale pink when they were built using bricks from the estate’s own brickworks, now a deep rusty red. Some of them, which are of double thickness, have the remains of grates at their base, in which fires were lit to heat the walls through a series of inner pipes so that fruit could thrive on them.

With his plans for the garden and landscape well and truly in place, Christopher was at last ready to turn his attention to the house and bring to fruition the schemes he had been harbouring for many years. He was always sketching. His diaries and pocket books are full of hastily executed drawings, and undated designs and scribbles abound in the Library cupboards at Sledmere.

His passion for architecture was no secret to his friends, who were only too ready to turn to him for advice when they were planning to build. ‘I have an alteration in view for the House at Tatton,’ wrote his brother-in-law, William, in February, 1783, ‘… I shou’d be happy in your advice about my proceedings.’27 For his West Yorkshire neighbour, Richard Beaumont, whose park at Whitley Beaumont had been laid out by Brown, he designed a pair of lodges to stand ‘at the end of the Avenue where those stood built by my father’. In spite of Beaumont’s enthusiasm for the project, Christopher himself appears to have been unhappy with the designs. ‘The lodges are begun,’ wrote Beaumont in September, 1783, ‘but the cellar only of one is dug. It was my intention to build one this & another next year. If the weather continues bad I shall not finish either of them this Year … Tho’ you disapprove of your Plan it is by no means disagreeable to me but if you will send me one more worthy of execution I shall be obliged to you. I intended the buildings to be exactly the size of those you sent me last Year … I have lost yr. Plan of those lodges & the gates & have only one copy of the lodges.’28

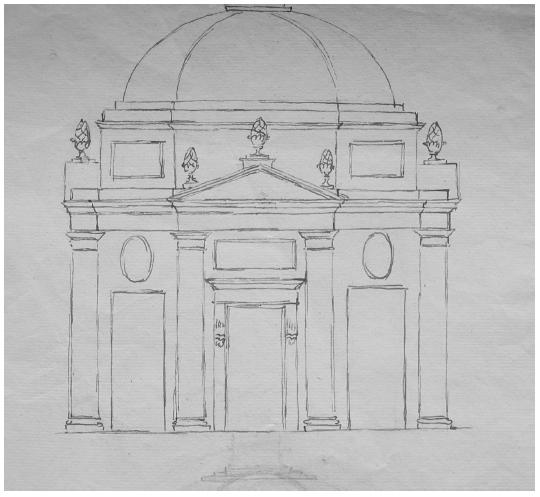

Because he was not a trained architect, Christopher was never in any doubt that he would require assistance on his Sledmere project. The first person to whom he turned was the architect of Castle Farm and the ice-house, John Carr, whose pedigree when it came to building large houses was matchless. A disciple of Robert and James Adam, he had worked on, amongst others, Harewood for Edwin Lascelles, Kirby Hall for Stephen Thompson, Constable Burton for Sir Marmaduke Wyvill, Temple Newsam for Lord Irwin and Kilnwick House for John Grimston, all Yorkshire houses of great importance. He had also built the stables at Wentworth Woodhouse for the Marquess of Rockingham and at Castle Howard for the Earl of Carlisle. At some point, possibly in 1786, though it is difficult to say this with certainty since none of the designs are dated and no reference to them appears in the Account Book, he came up with a plan for the principal, south, elevation of the new house, which was to be a very traditional seven-bay front with a central pediment supported by six Ionic columns. It was not chosen by Christopher, who would have considered it far too conventional and, perhaps, not nearly grand enough.

He next approached Samuel Wyatt, an architect whose practice was based in London, but who had undertaken two important commissions in Cheshire, one for Sir Thomas Broughton at Doddington Hall and the other for Sir Thomas Stanley at Hooton Hall. Christopher had met him through his in-laws, the Egertons of Tatton, with whom Wyatt had become acquainted while working on these projects and who were regular patrons of his. The first design he showed to Christopher was certainly imposing. It consisted of a seven-bay front with a shallow dome supported on columns – two single and two pairs – over the three central bays, all above arched ground-floor windows and a semicircular ground-floor porch. It was rejected by Christopher, possibly because he found it too fussy.

True to form, and probably what he had in mind all along, Christopher now tried his own hand, producing a scheme which married elements of both the Carr and Wyatt designs, but introduced a note of striking simplicity. Keeping the scale of the elevation the same, he reduced the seven bays to three, using tripartite windows on both the first- and ground-floor levels, with the central dome replaced by a pediment supported on two pairs of columns. Considering that Christopher was an amateur competing with two of the most renowned architects of the day, he made a remarkable job of his design, and it was upon his drawings that the final scheme drawn up by Wyatt was based. Gone would be the old-fashioned house built by Uncle Richard. In its place would rise up an elegant country seat in the very latest neo-classical style, that would be a monument to the success and aspirations of its owner. The main rooms, off a central staircase hall, were to be a library, drawing room, music room and dining room on the ground floor, and a long gallery on the first floor.

Most patrons building on the scale that Christopher was doing would have employed a competent builder or carpenter as clerk of works to oversee the progress of the project. This was how many young men who went on to become successful architects began their careers. Carr, for example, had worked in this capacity for the financier, Stephen Thompson, at Kirby Hall, and Wyatt for Lord Scarsdale at Kedleston. Characteristically, Christopher, as well as acting as executive architect, decided to be his own clerk of works, which brought an added cohesion to the whole scheme. It also meant that since he was the person corresponding with the various contractors, his preserved letters go a long way to telling the story of the building of the house.

The intention was to build two new cross-wings to the north and south of the 1750 house thus creating a new and much larger building on an H plan, the whole to be encased in Nottinghamshire stone. Work began in 1787. The stone proved problematical from the start, since it had to travel a great distance, and Christopher was to conduct a running battle with Mr Marson, the foreman of the stone quarry at Clumber, Nottinghamshire, from which it was dug. The grey limestone was then shipped up the River Trent to Hull, from where it was transported up the River Hull and the Driffield Canal to Driffield. It was then carried the last eight miles of its journey by wagon, a slow and arduous trip for the heavy horses who had to drag it uphill all the way from the flatlands of Driffield to the uplands of the Wolds. Obtaining it in the right sizes and quantities, at the right price and on time, provided him with many a headache. ‘Till the last load or two,’ he wrote to Marson in July, 1788, ‘when our Vessel arrived at Stockwith, there was only one Boat load ready for her & she had to wait for another Boat returning from the Quarry. That the additional Expence has been on our side & hope you will allow me ½d. a foot the disadvantage. But seriously I believe all sides will be well satisfied if you could have one Load upon the Wharf & two Boats loaded against the Vessel gets to Stockwith, & the Captain or master can tell them within a Day or two at most when that will be.’29