Полная версия

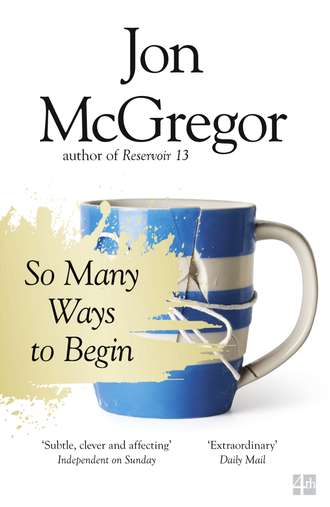

So Many Ways to Begin

At weekends, or on long evenings when the light held, he would work on the garden, swapping the dust of the building sites for the mud and soil of the ground. There were photographs, taken when they first moved into the house, in which the garden was nothing but piles of sand and builders’ rubble, a few nettles and thistles springing up from the odd patch of soggy ground. By the time he died, he’d turned it into something out of a gardener’s catalogue – a small lawn at the front, kept carefully trim and straight, bordered with rose bushes, hydrangeas, dahlias, and hollyhocks on either side of the front door. Long rows of vegetables in the back, carefully weeded, carrots and cauliflowers and brussel sprouts, potatoes and parsnips, wigwams of peas and fat runner beans.

Years later, when Dorothy first met Eleanor, she took great pleasure in showing her around the garden. This was all a wasteground when we moved in, David heard her say as she took Eleanor by the arm and led her around the borders. It took six years for the magnolia to flower but it was worth it, don’t you think? And Eleanor smiled and said that she thought it was. And as David watched them, from his place beside the back step, looking at the pale pink flowers of the clematis, which had been trained to the top of the slatwood fence, looking at the heavy handfuls of lavender and thyme growing out of the half-brick rockery in the corner, looking at the gnarled and sagging branches of the two small apple trees, it seemed as if his father had hardly gone away at all.

6 Postcard from Greenwich Maritime Museum, c.1953

When David told Julia that he wanted to be a museum curator she didn’t nod and say that’s nice, or make a face, or ask him why; she clapped her hands and said it was a wonderful idea. You’ll have to invite me to your first exhibition, she said enthusiastically and whenever he saw her after that she would ask how his collections were coming along, what lessons he’d learnt from the museums he’d been to since she saw him last, whether he’d have any jobs going for a work-shy duffer like her once he was open and ready for business. He started telling her about the sort of museum he would run, the exhibitions he would put on, the archives he would collect. I’ll have some displays that people can pick up and hold, he said, and more people to explain what things are. And I won’t have anything in storage, he said. It’ll all be out on display and if there isn’t enough room I’ll buy a bigger museum because it’s not fair to hold on to things and not let people look at them. And I won’t have any replicas or artist’s impressions, he said.

He reminded her about the boat he’d seen in the Maritime Museum; it was sitting in a small white-washed room of its own, beached on the bare floor and propped up by a pair of painted timbers. He’d walked around it, just able to see over the gunwales and into the plain interior, a couple of bench seats the only sign of comfort. The display panel on the wall had said that this boat, all twenty undecked feet of it, may well have been sailed across the Atlantic by the Vikings. He’d read those words over again and turned back to the boat, a storm of excitement breaking over him, pressing his hands against it breathlessly, wanting to climb in and run his hands all over it, to push his face into the rough-grained wood and smell the salt tang of sweat and sea and adventure, to sit on the bench and imagine the lurch of the open ocean, the endless tack and reach towards an unrelenting horizon. He’d looked at the wood, which must have been eight or nine hundred years old, and wondered why it wasn’t roped off from the public, why it wasn’t a little more crumbling and worn, why the varnish was gleaming under the spotlights. And he’d gone back to the display board, and read the last short paragraph explaining who’d built the replica and how, and he’d wanted to kick the whole thing to pieces.

It didn’t mean anything, he told Julia later. It wasn’t real, it was made up. You can’t learn anything about history by looking at made-up things, he said, talking quickly and urgently. It’s stupid, it’s not fair. It’s a lie, he said. They’re lying. She held up a hand to steady him, smiling at his earnest scorn. It’s better than nothing though, isn’t it? she asked gently. It gives you an idea at least, wouldn’t you say?

7 Opening programme, Coventry Municipal Art Gallery and Museum, 1961

It was still in good condition, kept clean and dry in a plastic wrapper, and when he slid it out to look through the pages the only marks of age were in the stilted language of the text and the starched formality of the photographs; the mayor, the director, the city treasurer, the benefactor’s wife, sitting on the platform with their hands folded into their laps, their hair waxed neatly into place, listening attentively to one another’s opening speeches, applauding.

He remembered their applause carrying out into the street, to the long crowd of people pressing and shifting back down the steps and away round the corner, five or six abreast, chatting and smoking and bending stiff legs, their hands stuffed into their pockets and their collars turned up against the last of the winter winds. One or two policemen were there, keeping order, walking up and down the line, asking people to keep out of the road and leave space for passers-by, keeping an eye out for light fingers and lost children. A pair of journalists were hanging around at the front of the queue, squiggling comments into a notebook, lifting a camera and encouraging people to smile, catching a shot where all the bleached white faces managed to look into the lens at once, a long stretch of them fading back into the dark evening; David near the front, waiting, unsmiling, half hidden by the heavy black coat of the man ahead of him.

The inky picture ended up on the front page of the Evening Telegraph, and the front page landed on the kitchen table for a while before being neatly clipped out and filed away into the box under his bed.

Didn’t it occur to you to smile? his father asked, standing and leaning over the paper, still dressed in his dust-plastered work clothes. Didn’t the photographer say cheese or something? David shrugged, embarrassed.

Wasn’t bothered, he said. Susan, who’d come through from watching television when Albert called, pulled the paper across the table and said let me see, where is he? She searched through the faces and found her brother, smiling in spite of herself, reluctantly impressed.

Fame at last, she said. You’ll have all the girls after you now. David ignored her, his face colouring, and leant over to try to read the article. Dorothy, standing at the oven to stir the gravy and check the chops and the potatoes, turned to Albert and said it’s almost ready now if you want to get changed. Albert waved his hand at her in passing acknowledgement.

Listen, he said, taking the paper back from Susan. Crowds gathered last night to be among the first visitors to another of our city’s proud buildings, the long-awaited Municipal Art Gallery and Museum. Guests were especially honoured to have in their midst the future director of the museum, one Mr David Carter Esquire, pictured here with a dirty great sulk on his face. David tried to pull the paper away, but his father whisked it up from the table and stood back, raising his voice above Susan’s laughter. The city treasurer, he continued, a tight-fisted bugger if ever we saw one, said it’s a shocking waste of money of course, but I was out-voted at the committee stage. It doesn’t say that does it? Dorothy asked, lifting her hand to her mouth as she realised her mistake. They all laughed, and she joined in, embarrassed, and they kept on laughing until Albert began to cough and splutter and double over in an attempt to haul in some breath.

You really should go to the doctor’s, Dorothy said when he’d recovered, handing him a glass of water. Albert didn’t reply.

And there was nothing now to show for this, in the archives he had kept. No medical records, no photographs of his father’s face turning a violent red as he fought for breath, no prescriptions or bottles of pills. Just the memory of that cough, the angry defiant bark of it, dry and choked, as though his lungs were full of tangled steel wool. There should have been something, at least. Something to hold up to the light, or to pin to the wall.

If he was asked, he was going to say that he remembered his father as a strong man; as someone who could balance two dozen bricks on his broad shoulders while he climbed a ladder, who could swing both him and his sister up in the air at the same time, and dig the whole vegetable patch over in the hour or two of light that was left after supper. He was going to say that he remembered his father as a busy man; as someone who always seemed to be in a hurry to be somewhere else: home from work, out to the garden, away from the supper table and out to join his friends in the pub. And he was going to say that he remembered his father as a loving man; someone who could hold his wife in his arms without shame and kiss her as if nobody else was in the room, someone who could find the time now and again to tuck his son into bed, with broad strong hands that smelt of soil and dust and cigarette smoke.

No one was much surprised when he died, and Albert was probably the least surprised of all. It had been coming on quickly for months and he seemed to have given up and started waiting for it. It feels like I’m breathing in tiny splinters of metal every time I open my mouth, he told David once. It feels like there’s a barrow-load of bricks weighing down on my chest. Dorothy found him when she got back from the shops one afternoon, his head tipped back over the arm of the sofa, a blanket wrapped around him like a shroud. She called out, and by the time David had run downstairs she was kneeling beside the sofa, holding Albert’s hand and stroking the side of his face. The shopping bags were on the floor, split open, tins and packets and loose wrapped meats spilt halfway across the room, and it was only when the doctor arrived that she pushed herself back to her feet again.

My father wasn’t one for talking much, he wanted to tell someone, and if he did it was never really about the past, about his family, or where he grew up, or what happened in the war. I know he was in the Navy and that’s about all, I don’t know where he went, or what he did when he got there, I don’t know what my mother went through at home when the bombing was going on, if she saw anyone killed or injured at all. I only know that they were apart for a long time, and they couldn’t even write, and that when they were together again there were things they didn’t feel the need to talk about; not even, I suppose, to each other. I think that’s how I got so interested in history, he would say, since there was so little of it at home. There weren’t even any photos on the wall until after my father had died.

I suppose I didn’t really know him all that well in the end, he thought he might say. Well, isn’t that the oldest story, someone might murmur in response, he thought, or, who among us ever did?

8 Two telegrams, November 1939 and April 1940

They’d spent the afternoon at the Imperial War Museum. He was still uncertain about finding his way around London on his own, so Julia had gone with him, and had been very patient while he took notes and made sketches, and had gone quiet at one or two of the exhibits, stepping away a few paces and turning her back so that he knew it wasn’t a good idea to ask her what was wrong. They’d found a Christmas tobacco tin from 1916, like the one she had at home from her father, but this one was empty and she’d laughed and whispered maybe it’s worth something now, and he’d been shocked by the idea of her selling such a thing until she’d nudged him and he’d realised she was joking. It hadn’t been until they were on the bus on the way home, the street lamps already spilling splashes of light on to the rain-polished streets, that he’d asked about her own experience of the war, and about her husband; and it was only after they’d run from the bus stop to the house, and wrapped their wet heads in warm towels from the airing cupboard, and sat down in the kitchen with a steaming pot of tea and thick slices of heavy cake, that she’d begun to tell him.

The war hadn’t started when I met him, she began, but everyone knew it wouldn’t be long in coming. She hadn’t got very far with her story before she realised he didn’t know what she meant by ballroom dancing, so she insisted that she teach him there and then. She put a record on, and had him push the table back, and talked him through the steps while a waltz crackled out of the small loudspeaker. He felt a tightening knot of embarrassment in his stomach as she took his hand and placed it on her waist, and laid her hand against his, but he knew there’d be no getting out of it until he’d got it right. So he listened, and he concentrated, and he started to relax a little, and the second time the record played he only stepped on her foot twice. Well! she said, clapping her hands as the record finished again, I think we’ll make a ballroom maestro out of you yet, young man. We’ll have the debs of London queuing up for you! He didn’t know what she meant by debs, but he didn’t get a chance to ask. Once more, she announced, as the needle jerked back to the start of the record. This is the way the story begins, she said, taking his hand.

A Friday evening in early June, 1939. A hotel ballroom just off The Strand, its high domed ceiling frescoed pale sky-blue with wisps of spindrift clouds, ringing with the fading echo of the orchestra’s closing bars. A renewed rumble of chatter and a tinkle of glasses. A brief light-fingered applause for the musicians. The dancers returning to their seats, singly or in pairs, smiling and no-thank-you-ing, reaching for drinks with lowered eyes and private blushes or whispering reports to a neighbour’s ear. A rustle of loose sheaf paper at the orchestra’s music stands. The unaccompanied glide and twirl of the white-jacketed waiters refreshing tall glasses with a stoop and a bow, proffering hors d’oeuvres on broad silver trays, wordless, indifferent, impeccably polite. Seated guests rising for the next dance, taking the hand of those closest to them, or catching the eye of another nearby, or crossing the room with a smart-heeled step, a discreet straightening of the jacket, a two-fingered smoothing of the hair; determined, after much raw-humoured ribbing, to finally take the bull, as it were, by the horns.

We’d been watching each other all evening, she told him as the first few bars of the music swelled up against the sound of the rain outside and David led them correctly away to the right, towards the tall potted yucca. That’s it! she said. You’re getting it now, back two three. I’d noticed him almost as soon as he came into the room, she said. The smart cut of his uniform, you know, and an awfully manly jaw, and very clear pale eyes. I caught him looking a few times, she said, smiling. Or he caught me looking, she added; turn two three. I suppose it depends which way you look at it. She laughed.

Major William Pearson stood in front of Julia’s table and introduced himself. Neither of them were surprised that he was there, after an evening spent watching each other’s movements – checking who the other may or may not be dancing with, hazarding a smile from across the room, murmuring excuse me as they came close to colliding by the doors to the terrace – and neither of them expected her to decline his invitation to dance. But still, she went through the formalities of reluctance, and her friends carefully looked away and pretended not even to have noticed that the gentleman they’d discussed all evening had finally crossed the floor to their table, and was as smoothly good-looking close up as he was from afar. He insisted, politely, and she stood, churning with excitement, and accepted his outstretched hand. Thank you, she said. I’d be glad to.

They strode to the middle of the room, offering each other their hands and waists just as the conductor was tapping his podium. William smiled, and their dance began. Neither of them said very much at first, beyond an exchange of polite enquiries, a compliment on the other’s dancing, a remark on the weather, concentrating instead on their crisp and flowing movement around the circular stage of the room. Moving away from her table, where her friends were speaking into their hands and offering gestures of encouragement as she looked over his shoulder towards them; turning across the floor to within earshot of her mother and father, her father looking rather glazed, her mother smoking a cigarette in an ivory holder and dropping her a wink in the middle of one of her actress friends’ long anecdotes; past a table of boys she recognised from the school opposite hers, boys she’d once gossiped about and spied upon but who from the vantage point of Major William Pearson’s arms now looked far more like boys than the men they were trying so hard to be with their fuzzy moustaches and their freshly signed papers; deftly sidestepping a waiter with a tray of drinks; twirling quickly away from a raucous gaggle of tail-coated medical students; changing direction, and pausing for a brief moment, in front of his table by the corner of the stage, the officers of his party in uniforms as smart as his, raising their glasses and making comments from the sides of their mouths before roaring with laughter and slapping each other’s knees – ignore them, he said quietly, smiling a little nonetheless – and she blushed and dropped her eyes for a moment; sweeping past the orchestra which seemed to be playing for the two of them alone, as if nobody else was there, and although she’d partnered dozens of men in that same dome-ceilinged venue, and although the music was more than familiar, the dance still felt brand new for them both.

They found themselves talking a little more, confident in their dancing, asking about each other’s lives, his short career in the army, her studies at drama school and her hopes of following her mother on to the stage. He talked about the prospects of war, the slim chance of it still being avoided. They both described their favourite walks, restaurants, pastimes, and they were both surprised by how soon they were sharing these small secrets and intimacies. And as they talked, almost forgetting that they were dancing at all, quite forgetting that others were dancing around them, or that they were not passing unobserved, they found that they were holding each other a little closer, a little firmer, his hand resting lower on her waist, his chest brushing lightly against hers, their hips even pulling tightly together once or twice; and they found that their voices were dropping lower, taking on a secretive inviting tone obliging the other to lean in a little closer to hear, tilting their heads to whisper in each other’s ear, turning their faces to catch the murmuring lips against their cheeks.

I still don’t really understand how it happened, she told David, dancing past the record player. I wonder if anyone really understands how it happens, when it’s like that, so immediate. How could we possibly have known what we were doing? What did we think we knew about love, or any of that business? He didn’t know how to answer her. He wasn’t sure if she was still talking about one dance, one evening, or the first weeks and months of their being together. He didn’t really understand her questions, and he was too busy concentrating on matching their steps to the music without colliding with the furniture. But she wasn’t really asking him at all, he realised later; she was asking the photograph of Major Pearson on the wall, or the music which skipped and bumped beneath the worn-out stylus, or the rain which spattered against the windows outside.

Later, she told him how reckless she thought they’d been. He presented it as a matter of practicality, she said, almost the same day as war was declared. He said that he’d soon be leaving for France, that an opportunity had arisen for the purchase of a house, this house, which would be unsuitable for a bachelor. He said there was no benefit to our endlessly hanging around. But the truth really, David, is that we were stupidly and drunkenly in love. We didn’t quite stop to think, she said. Not that I would have had it any differently of course, she added, but one does wonder.

One does wonder was a phrase she often repeated, always pausing before correcting herself in one way or another. But he was such a handsome man David! Such a handsome and exciting man! And when you’re young nothing else very much matters, does it? Only that this handsome chap is offering you a ring and wants you to be his wife. Patience and caution weren’t really in my vocabulary in those days, she told him, smiling, and he replied, teasingly, that he didn’t think they would ever be.

And as the record started again – we danced for a very long time, she told David; it seemed to go on for ever but then it was over far too soon – Julia and William danced once more around the room, past her friends, past his colleagues, past the waiters and the medical students, and back to her parents, pausing and turning while William cocked an eyebrow at her father, inclining his head towards Julia, and her father nodded, lifting up the palm of his hand as if to say certainly, be my guest, and they turned, stepped, stepped, turned away, their waltz bringing them over to the centre of the room where William dropped quickly to one knee. The conductor raised his baton, the musicians paused and the whole room leant forward to listen. Yes of course, she said. I’d be glad to, she said. And the music resumed, and the whole room applauded, and the pace of their dancing quickened as they whirled back and forth across the floor, rushing to make the arrangements, a best man, a bridesmaid, a church and a vicar, choosing the hymns and booking the hotel room, and before she knew quite what was happening her father had taken her by the arm and danced her down the length of the room, up past a pressing throng of friends and well-wishers, up to where the vicar waited and nodded his head in time to the waltz. Will you? he intoned to Major Pearson, and Major Pearson replied I will. Will you? he asked of Julia, and Julia smiled. Of course, I will. The vicar joined them hand in hand, and they danced back down the hall, confetti showered at their feet, William’s colleagues lining up to form an archway with their bayoneted rifles, a waiter leading the shout of hip-hip-hooray as Major and Mrs Pearson danced right out through the doors and into the hotel lobby, sweeping up the thickly carpeted stairs and straight into the first available room, William lifting Julia into his arms and slipping a coin into the bellboy’s hand.

And when they emerged, sometime later, the music was still playing. So they waltzed back down the stairs into the ballroom, and it seemed as though no one had noticed their return, the whole room dancing together now, and when Julia looked around she saw faces fixed with concentration, eyes focused on distant points beyond the room, people moving with a stiff-limbed determination, lips pulled up into forced blank smiles.

David had long sat down by then, too embarrassed to dance any more, muttering that he thought he had the hang of it and he was out of breath. But Julia had barely seemed to notice him moving away, still stepping around the room with her hands held out in front of her. She was talking quickly, stumbling, not looking at David or following the music, saying and then, and then, no, that’s not right, we, and then, as if everything had happened all at once, in that one room, on that one night, and not in the space of a few hurried months.

We only had a few days, she said, before he went away. It was difficult not to think about it, she said, raising her voice against the rain, turning to a slow halt, her hands falling to her sides, her face lined with shadows. The details of her story were becoming confused, and she seemed breathless, unsteady, nodding slightly in time with the music or in agreement with her own muddled recollections. He wanted the music to stop, or Julia to say something like, well really I think that’s enough for now, let me just sit down, but she didn’t. She leant back against the writing bureau, her eyes half-closed and her hands seeming to conduct the music, and she carried on talking.