Полная версия

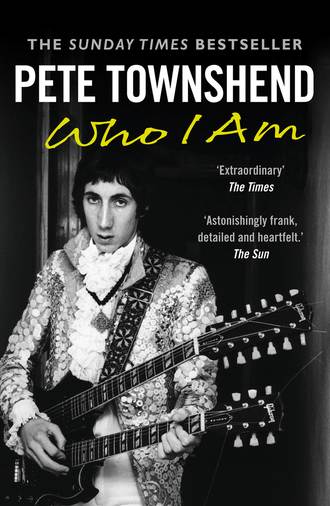

Pete Townshend: Who I Am

Why did that even matter? Wasn’t it enough that I had helped discover guitar feedback? I had certainly invented the power chord. With Ray Davies I had introduced the suspended chord into UK pop. But none of this felt like enough. Something dangerous and new was happening in music, and I wanted to be part of it.

While Jimi Hendrix conquered London, The Who’s first performance in the USA was almost an accidental event. Frank Barsalona ran Premier Talent, an agency in New York. He heard about The Who through someone in Brian Epstein’s camp, and was persuaded to put us on the bill of an annual New York package with the famous Murray the K, the first American DJ to get really close to The Beatles. Murray had also been tipped off about Eric’s new band Cream. The shows were planned to take place over a two-week period, during which we were expected to perform six shows a day, so we anticipated an intense period of work.

Flying into New York was a first for my bandmates. Having made two trips there on my own in connection with what became the Allen Klein takeover bid, I felt fairly at ease in the city. Keith and John were so excited they could barely contain themselves, and immediately started living in high style at the Drake Hotel, Keith ordering vintage champagne and John a trolley of several brands each of Scotch, brandy and vodka. The bill was astronomical, and the waiter chided Keith for giving him only a $20 tip. We ate our first real ‘chopped sirloin’ steak there, a big $15 hamburger. I think that’s all I lived on during my stay.

The shows in New York in spring 1967 were a smash for both The Who and Cream. Contrary to the drudgery I’d expected, this was one of the most wonderful two weeks of my life, and certainly the time when I fell in love with New York, a passion that has withstood the test of time.

At the RKO 58th Street Theatre, where the shows would be taking place, we convened for a sound-check and pep talk from Murray the K. By now he had rather lost his ‘Fifth Beatle’ glow; his toupee was dusty and he sweated a lot. He insisted on having a gold-plated microphone, which no one else was allowed to touch, as well as the largest dressing room, which didn’t meet his standards until a star was hung on the door. His address to the bands brought out the worst in me; I hated what I saw as his inflated absurdity, even though I knew Murray the K had been a vital part of breaking British music on American radio. He seemed to have delusions of being a great showman. And perhaps he was.

Murray the K may not have been in his prime, but he did put together an amazing group of musicians. On the regular bill was Wilson Pickett, who took great delight in using Murray’s personal gold microphone whenever he could lay his hands on it. One day Simon & Garfunkel headlined; another The Young Rascals. It was basically a pop-music festival. A real sense of camaraderie developed that, in the end, extended all the way to Murray himself.

What is more difficult to describe is what happened in the audience during that series of shows, simply because we weren’t out there on the folding seats. Legend has it that, because one ticket purchased allowed you to stay all day if you wanted to, a large number of young people attended every single show, partly to find out when The Who would run out of equipment to smash.

While I laboured backstage with soldering iron and glue, rebuilding smashed Fender Stratocasters, The Who’s New York fan base was being built from human kindness and affection never equalled anywhere else on earth. If I set up a mattress on Fifth Avenue today, I could live for the rest of my life on the beneficence and loyalty of our New York fans. I still know at least twenty of those RKO kids by name. I know at least a hundred faces. I know the names of some of their parents. Several kids have come to work for me at various times over the years, and some have written books or made movies about us. Some simply watched, grew up and did everything they went on to do with the same dedicated, compulsive lunacy they saw in us as we performed. We advanced a new concept: destruction is art when set to music. We set a standard: we fall down; we get back up again. New Yorkers loved that, and New York fans carried that standard along with us for many years, until we ourselves were no longer able to measure up.

On our return to England I drove Eric Clapton and Gustav Metzger, the auto-destructive artist whose ideas first inspired me, down to Brighton Pavilion where we were playing with Cream; Gustav was doing the lightshow. Compared with Jimi’s shows I found Cream a little dry when they played a longer set. I wanted to see Eric do something more than just long, rambling guitar solos, just as I wanted something more from myself than silly pop songs and stage destruction.

It was the first time Gustav had seen my version of auto-destruction in process, and though he was pleased to have been such a powerful influence he tried to explain that according to his thesis I faced a dilemma; I was supposed to boycott the new commercial pop form itself, attack the very process that allowed me such creative expression, not contribute to it. I agreed. The gimmicks had overtaken me.

***

I remember going to a lunch gathering with Barry and Sue Miles. Barry was a founder of the Indica Bookshop, a radical establishment selling books and magazines relating to everything psychedelic and revolutionary. I met Paul McCartney properly there, with his girlfriend, actress Jane Asher. Paul had helped fund Indica, and he seemed much more politically savvy than any other musician I’d come across. He was clear-thinking and smart, as well as charming and essentially kind. Jane was well-bred, polite and astonishingly pretty; behind the demure exterior simmered a strong personality, making her the equal of her famous beau.

George Harrison arrived a little later with his girlfriend, Pattie Boyd. Pattie was immediately open and friendly. She had the kind of face you could only see in dreams, animated by a transparent eagerness to be liked. Karen was with me, and for the first time I felt part of the new London pop-music elite. Karen, strangely, seemed more comfortable than I was.

I saw Paul again at the Bag O’Nails in Soho, where Jimi Hendrix was making a celebratory return. Mick Jagger came for a while and then left, unwisely leaving Marianne Faithfull, his girlfriend at the time, behind. Jimi sidled up to her after his mind-bending performance, and it became clear as the two of them danced together that Marianne had the shaman’s stars in her eyes. When Mick returned to take Marianne out to a car he’d arranged, he must have wondered what the sniggering was about. In the end, Jimi himself broke the tension by taking Marianne’s hand, kissing it, and excusing himself to walk over to Paul and me. Mal Evans, The Beatles’ lovable roadie-cum-aide-de-camp, turned to me and breathed a big, ironic Liverpudlian sigh. ‘That’s called exchanging business cards, Pete.’

***

The Who had several roadies from Liverpool at this time, who seemed to operate on the assumption that there was a moral gulf between London and their home city. One of them took five or six of my broken Rickenbacker guitars home for his father to repair, and I never saw them again. The other developed a compulsion for stealing hotel furniture, emptying an entire room once while the band was still on stage around the corner. He even took the wardrobes and the bed, all of which were added to our hotel bill. When these thefts were brought to their attention they made us feel as if we were making a fuss over nothing.

By contrast, Neville Chester, our first official road manager, was excellent and hard working. We were difficult to please in the best of circumstances, and the equipment smashing meant that a lot of his free time was being spent chasing up repairs. When he became associated with Robert Stigwood and began to appear wearing rather posh suits, we feared Stiggy had made him an offer he couldn’t refuse. In any event, we lost him as road manager.

We then found the amazing Bob Pridden, who is still our chief sound engineer today. Bob’s first important show should have been at Monterey, but for some reason Kit and Chris felt we should take Neville instead, for one last job with us. I haven’t seen him since, but he played a vital part in our early career, and should receive a massive royalty share for everything he did.

That should flush him out.

The Who headed back to the States in June, flying out on the 13th, the day after Karen’s birthday, to play at Ann Arbor, Michigan, our first show outside New York. We then moved on to play four shows in two days at Bill Graham’s Fillmore in San Francisco. Cannonball Adderley was on the bill with his brother Nat, and I couldn’t wait to tell them how much I loved ‘Tengo Tango’.

Bill Graham told us firmly we had to play two one-hour sets with no repeats. We had rarely played more than fifty minutes, and most of that was filled by me, making my guitar howl. Suddenly I started to see the sense of Eric Clapton’s extended soloing. We rehearsed and brought in new material, and the attentiveness of the Fillmore audience and excellence of the PA system more than made up for the extra work. It made us feel for the first time that we were playing real music.

The atmosphere in Haight-Ashbury was peace and love, the streets full of young people tripping. The ones to watch out for were the many Vietnam veterans, attracted by the promise of easy sex. They were often badly damaged by their wartime experiences, and despite the mellowing drugs they took they could be pretty hostile. One man grabbed Karen’s arm as he passed and wouldn’t release it, gazing at her like he’d found his Holy Mother. I caught his attention by knocking his arm away; for a second his face hardened, then he broke into a grin and walked away.

It was at the Monterey Pop Festival, on 18 June 1967, that Jimi and I met our battleground. Essentially it was a debate about who was on first, but not quite for the reason one would assume. When Derek Taylor, The Beatles’ former publicist who was acting for the festival, told me we were to appear immediately after Jimi, two thoughts ran through my head. The first was that it seemed wrong that we should appear higher on the bill. Musically speaking, Jimi had quickly surpassed The Who; even then he was far more significant artistically than I felt we would ever be.

I also worried that if Jimi went on before us he might smash his guitar, or set it on fire, or pull off some other stunt that would leave our band looking pathetic. We didn’t even have our Sound City and Marshall stacks because our managers had persuaded us to travel light and cheap. Jimi had imported his, and I knew his sound would be superior.

Derek Taylor suggested I speak to Jimi. I tried, but he was already high. He wouldn’t take the question of who would perform first seriously, flamming around on his guitar instead. Although I don’t remember being angry, and I’m certain I wouldn’t have been disrespectful, I knew I had to press Jimi to engage me. At this point John Phillips of The Mamas and Papas intervened, thinking we weren’t being ‘peace and love’ enough. He suggested tossing a coin, and whoever lost the toss would go on last. Jimi lost.

After being introduced by Eric Burdon, The Who blasted through a clumsy set, ending by smashing our gear. The sound technicians tried to intervene as we went into our finale, which only added to the sense of disarray. The crowd cheered, but many seemed a bit bewildered. Ravi Shankar was apparently very upset to see me break my guitar. I towelled myself off and ran out front to catch Jimi’s set.

It was strange seeing Jimi in a big music festival setting after only having seen him in small London clubs. Many of Jimi’s stage moves were hard to read from where I was sitting. In the huge space Jimi’s sound wasn’t so great after all, and I started to think maybe The Who wouldn’t compare too badly. Then he turned up his guitar and really started to let loose: Jimi the magician had made his appearance. What was so great about him was that no matter how much gear he smashed, Jimi never looked angry; he always smiled beatifically, which made everything he did seem OK.

The crowd, softened up by The Who’s antics, responded heartily this time. When Jimi set his guitar on fire, Mama Cass, who was sitting next to me, turned and said, ‘Hey, destroying guitars is your thing!’

I shouted back over the cheering, ‘It used to be. It belongs to Jimi now.’ And I meant every word.

When Karen, Keith Altham (our publicist) and I all gathered at San Francisco airport to fly home, it turned out that Keith had also been working with Jimi, who was allegedly also paying his fees. I made it clear to Keith that I felt he had been duplicitous by not telling us he would be acting for both The Who and Jimi at Monterey. He denied any wrongdoing, and defends himself to this day.

Jimi got wind of our little spat in the airport lobby and started giving me the evil eye. I walked over to him and explained that there was no personal issue involved. He just rolled his head around – he seemed pretty high. Wanting to keep the peace, I said I had watched his performance and loved it, and when we got home would he let me have a piece of the guitar he had broken? He leaned back and looked at me sarcastically: ‘What? And do you want me to autograph it for you?’

Karen pulled me away, fearing I would blow up, but the truth is I was just taken aback. Contrary to what I’d been told, Jimi must have been as ruffled as I was by the reverse jockeying for position before the concert.

As Karen and I boarded the plane in San Francisco, Keith, John and Roger seemed unfazed by what had passed between Jimi and me. We settled into our TWA first-class seats, which in those days faced each other over a table. Keith and John produced large purple pills we’d all been given by Owsley Stanley, the first underground chemist to mass-produce LSD, and Keith popped one. These pills, known as ‘Purple Owsleys’, had been widely used at the festival.

As the plane took off, Karen and I split half a pill. John wisely demurred. Within an hour my life had been turned upside down.

1 This was used as the basis for ‘I Love My Dog’, released in autumn 1966 by Cat Stevens, and an immediate hit. Cat (born Steven Georgiou, later renamed Yusuf Islam) now pays back-royalties to Lateef. I remember him fondly – I spoke to him once in Brewer Street when he was a teenager. His family owned a restaurant around the corner from my Wardour Street flat. He was three years younger than me, but that would have been quite a gap between such young men. He had caught me in my big, blue Lincoln, seemed to know of me and where I lived, and fired a number of questions at me about songwriting and guitars.

10 GOD CHECKS IN TO A HOLIDAY INN

The Owsley LSD trip on the aeroplane was the most disturbing experience I had ever had. The drug worked very quickly, and although Karen and I only took half as much as Keith, the effect was frightening. Seasoned trippers have teased me since about how stupid we were, but Karen and I felt that Keith couldn’t be allowed to trip alone, and that we’d all be able to help each other. In fact Keith seemed to operate in total defiance of the drug’s effects, only occasionally asking how much we had taken to check if he was getting it worse – or bigger and better – than we were.

At one point I tried to console Karen, who was terrified, telling her I loved her. ‘Ah!’ Keith sneered, and John cynically joined in. Roger, sitting across the aisle, may have found the whole thing amusing, but I was reassured by his smile. After thirty minutes the air hostess, whose turned-up nose had made her look a little porcine, transmogrified into a real pig, scurrying up and down the aisle, snorting. The air was full of faint music, and I wondered if I was experiencing my childhood musical visitations again, but I finally traced the sound to the armrest of my seat. After putting on a headset I felt I could hear every outlet on the plane at the same time: rock, jazz, classical, comedy, Broadway tunes and C&W competed for dominance over my brain.

I was on the verge of really losing my mind when I floated up to the ceiling, staying inside the airframe, and watched as everything changed in scale. Karen and Pete sat below me, clutching onto each other; she was slapping his face gently, figuring he had fallen asleep. From my new vantage point the LSD trip was over. Everything was quiet and peaceful. I could see clearly now, my eyes focused, my senses realigned, yet I was completely disembodied.

I looked down at Keith picking his teeth, characteristically preoccupied, and at John reading a magazine. As I took this in I heard a female voice gently saying, You have to go back. You cannot stay here.

But I’m terrified. If I go back, I feel as if I’ll die.

You won’t die. You cannot stay here.

As I drifted back down towards my body, I began to feel the effects of the LSD kicking back in. The worst seemed to be over; as I settled in the experience, though extreme, felt more like my few trips of old: everything saturated by wonderful colour and sound. Karen looked like an angel.

John Entwistle married his school sweetheart, Allison, on 23 June, while the band spent a fortnight in London before returning to America for a ten-week tour supporting Herman’s Hermits, on what was to be their swan song. During this interlude Karen and I decided to look for a flat together, and found a perfect place in Ebury Street, closer to Belgravia. The flat comprised the top three floors of a pretty, though conventional, white Georgian house. The lease was short, and a great bargain, but the flat wouldn’t be available until autumn, which seemed a hundred years away.

Karen didn’t join me on the road – Herman’s managers wouldn’t allow that – but she did go to New York, staying with her friends Zazel and Val; when the band got close to the city I would try to hook up with her. I got a sense at one point that someone had actively and persistently pursued Karen while I was on the road. I heard a rumour that a musician or artist friend of Zazel’s boyfriend had been joining them on dates. At first I was insanely jealous, but I soon realised that this was the way things were. If one of us got swept away, then so be it.

The Who left London in early July 1967 and didn’t return until mid-September. This was our indoctrination into the real America. We touched down in almost every important town or city, and in quite a few places we’d never see again. On this tour we listened to Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and not much else. The shockwave it caused challenged all comers; no one believed The Beatles would ever top it, or would even bother to try. For me Sgt. Pepper and the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds redefined music in the twentieth century: atmosphere, essence, shadow and romance were combined in ways that could be discovered again and again. Neither album made any deep political or social comment, but ideas were not what mattered. Listening to music had become a drug in itself. Keith Moon had become convinced he was ‘Mr K’ in The Beatles’ song ‘For the Benefit of Mr Kite’ from Sgt. Pepper. He played it constantly, and his ego began to get out of control. It could just as easily have been about Murray the K.

San Francisco was full of pharmaceutical gurus and New York was arguably the capital of the world, but some places in between felt reactionary in the extreme. In the South we were banned from swimming pools without bathing caps because our hair was too long, and nearly beaten up by men who took offence at what they saw as our obvious homosexuality. Even women, especially older ones, were open in their derision. We hadn’t been prepared for Middle America’s prejudices.

Yet at a Florida motel Herman (Peter Noone) had sex with a pretty young fan and her pretty young mother at the same time. When the two females emerged from his room together, we gazed in stupefaction. At one swimming pool a blonde girl in a bikini fluttered nervously around me. I was starting to chat her up when Roger took me aside and whispered: ‘Jail bait!’ In her bikini she looked like a woman to me.

Occasionally, on our rare days off, we got really drunk. One day Keith and I were walking along the second-floor balcony of a Holiday Inn when Keith suddenly climbed over the railing and leapt into the pool below. I followed, but miscalculated – I was falling not into the pool but towards its edge. I wriggled as I fell, managing to just scrape into the pool, badly grazing my back and one arm. I might have broken my neck, or my back. I should have known better than to emulate Moon’s antics, drunk or not.

Roger and his American girlfriend Heather, who had dated Jimi Hendrix and Jeff Beck among others, established an aristocratic rock relationship, and Roger began to appear more certain of himself, and more comfortable as a singer. The tensions of the past were receding. On this road trip I felt no responsibility to act as principal architect of The Who. I just played my guitar during our twelve-minute warm-up for Herman’s Hermits. The concerts made for a strange culture clash: we smashed our guitars and screamed about our disaffected generation, whereas Herman sang about someone who had a lovely daughter, and the fact that he was Henry the Eighth, he was.

On this tour we had less to do than we would have liked. I read Heinlein and Borges and tried to stay settled. Although today this sounds to me the perfect life, it didn’t feel that way at the time. For the first half of the tour I carried no tape machine; instead I drew diagrams of my studio back home, and began to consider various new approaches to recording. Later I would find that many of the ideas I was scribbling down were already becoming industry secrets, thanks to the efforts of engineers working with Brian Wilson and George Martin, The Beatles’ producer.

One idea involved laying off a guitar solo on a separate piece of two-track tape, replacing all the spaces in the solo with blank tape, inverting the tape and playing a new solo matching the old but backwards. Another involved tape loop chord machines operated by foot pedals; tape sampling had been invented in the Mellotron, a kind of organ used by The Beatles that used loops of tape triggered by a conventional piano keyboard. I also suggested recording loops of white noise and tuning them to make it musical. I described techniques for creating extreme reverb effects using tape delays combined with echo chambers, reverb through revolving organ speakers and through guitar amplifiers with the vibrato unit turned on; all these effects became part of my home studio creative arsenal.

I commissioned a small low-power radio transmitter that would simulate a true radio sound to check how my tracks would sound if they were ever broadcast. I was already experimenting with stereo ‘flanging’, taking two identical tracks and bringing them in and out of phase with each other to create a psychedelic effect. I built a speaker in a small box, attached a tube and put the tube in my mouth, allowing me to ‘speak’ music. When Frank Zappa leaned over to me conspiratorially at the Speakeasy Club in London and described this new invention to me, I was polite enough not to tell him I’d already come up with it.

In New York, The Who did a show on Long Island, then we went to the Village Theater to support Al Kooper’s Blues Project. On the same bill was Richie Havens, an intense, engaging man and an effervescent, unique performer. His acoustic guitar was usually tuned to a particular chord, and he sang his full-throated songs so powerfully that he sounded like a band in himself. My old buddy Tom Wright said that when you shook hands with Richie you had to be the one to break the shake first, otherwise you could be there, gazing at his beaming smile, for all eternity.

When the Hermits’ tour hit Baton Rouge, the tour manager warned us that there had been recent race riots: we were to be on our best behaviour, and vigilant for trouble. There was a possibility our show there would be cancelled. We were all hyped up, but there was no obvious sense of tension, no visible problem. We were aware that the race issue had caught fire in the South, but at the time we didn’t feel part of the battle.