Полная версия

The Cruel Victory: The French Resistance, D-Day and the Battle for the Vercors 1944

‘Yes, M’sieu.’

‘Are you aware that life in the Maquis is very hard?’

‘Yes, M’sieu.’

‘Do you understand the risks involved – great risks?’

‘Yes, M’sieu.’

‘And you know how to keep your tongue, do you?’

‘Absolutely, M’sieu.’

‘OK. Go to the Fontaine halt on the tramway which takes you up to Villard at five o’clock tomorrow evening. Ask for one of the Huillier brothers and tell him discreetly that you have come to see “Casimir” – that’s the password. He will tell you what to do next. Follow his instructions closely and without any questions. Take a rucksack with what you need. But be careful. Don’t take too much. You must look like a casual traveller.’

The young man nodded and left the room, closing the door behind him.

Eugène Chavant took out a small piece of paper and wrote a message for his friend Jean Veyrat: ‘There will be one colis [package] to take up to Villard tomorrow evening.’

The following evening a Huillier bus set the young man down in the main square of the town of Méaudre on the northern half of the Vercors plateau. Here, following his instructions, he went to a café in one of the town’s back streets where he found he was among a number of young men who likewise seemed to be waiting for something – or someone. A short time later an older man arrived. He was wearing hiking clothes and boots and carried a small khaki rucksack.

‘Follow me,’ he said, and led the way out of the café and into the darkness.

The little group walked north along back roads for forty minutes or so and then took a short break before starting to climb steeply up the mountain. Half an hour later they entered a forest and five minutes after that their guide stopped in the darkness and gave three low whistles. Out of the night came three answering whistles. A guide emerged from the trees and led the little group of newcomers to a shepherd’s hut in a clearing in the forest. Though it is doubtful that any of them realized it, they had all taken an irreversible step out of normality, into the Maquis and a life of secrecy and constant danger. One way or another, their lives would never be the same again.

As German demands for manpower increased, the trickle of réfractaires turned into a flood. The numbers at the Ambel farm quickly rose to eighty-five. There was no more space. In Eugène Samuel’s words, ‘The young men coming up the mountain became more and more numerous. Now it was not just the specialists who were being called away, but whole annual intakes of young men whom Laval wanted to send to help Hitler’s war effort. There was a mood of near panic among the young men, and the resources of the Gaullist resistance organizations were very soon swamped. We needed new camps; we needed more financial resources; we needed food; we needed clothes and above all we needed boots. We needed to organize some kind of security system to search out the spies who we knew the Milice were infiltrating with the réfractaires. We needed arms.’

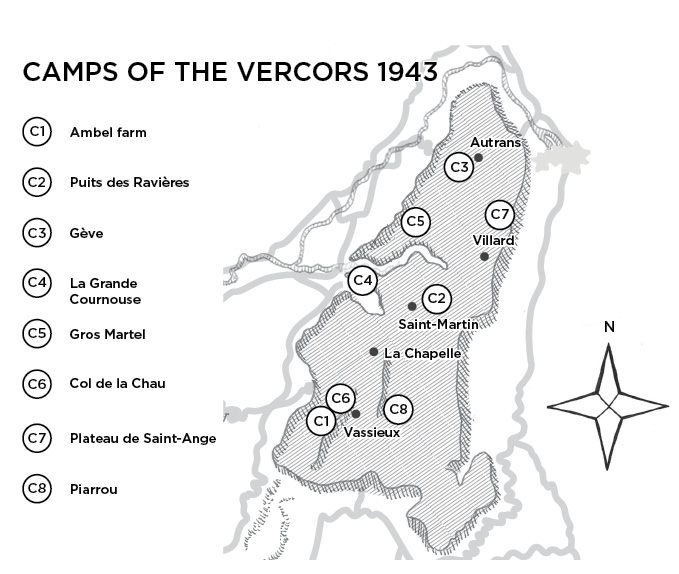

New camps were soon found. And not just in the Vercors. Elsewhere in the region, other early Resistance groups were also establishing camps for fleeing réfractaires in the remote areas of the nearby Chartreuse Massif and the Belledonne and Oisans mountain ranges which bordered the Grésivaudan valley. Between February and May 1943, eight new réfractaire camps – housing some 400 men in all and numbered consecutively from Ambel (C1) – were established across the Vercors plateau under the direction of Aimé Pupin. To this total must be added two military camps, one set up in May by an ex-Military School in Valence, another established in November under the control of Marcel Descour.

Map 3

Those who joined the camps between March 1943 and May 1944 (that is before the Allied landings in Normandy) were of differing ages and came from a wide area. In a sample of forty-four réfractaires in the initial influx between March and May 1943, almost half were over thirty years old, many of them married. As might be expected, the majority (60 per cent) were from the immediate locality (the region of Rhône-Alpes), but among the rest almost 10 per cent were Parisians, a further 10 per cent were born out of France and nearly 15 per cent came from the eastern regions of France. There was similar diversity when it came to previous employment. In C3, above Autrans, nearly half the camp members had been ordinary workers, almost a third technicians of one sort or another, some 12 per cent were students and nearly 10 per cent had been regular soldiers. Politically, too, there was a broad variety of opinions and views. The fact that the great majority of the Vercors’ civilian camps were loyal to de Gaulle meant that the organized presence of the Communists and the French far right was almost non-existent on the plateau. Individually, however, the camps included adherents to almost every political belief (except of course fascism). Political discussions round evening campfires were frequent, varied and at times very lively.

By autumn 1943, every community of any size on the plateau had a secret camp of one sort or another near by – and every inhabitant on the plateau would have been aware of the unusual nature of the new young visitors in their midst. For Samuel, Pupin, Chavant and their colleagues, the administrative burden of all this was immense. Pupin later said: ‘We didn’t have a moment of respite. Our eight camps occupied our time fully.’ The biggest problem by far, however, was finding the money to pay for all this. Collections were made among family, well-wishers and workplaces – two Jewish men contributed between them 20,000 francs a week which they had collected from contacts. But it was never enough.

London started providing huge subventions to support the réfractaire movement. During Jean Moulin’s visit to London in February 1943, de Gaulle charged him with ‘centralizing the overall needs of the réfractaires and assuring the distribution of funds through a special organization, in liaison with trades unions and resistance movements’. On 18 February, Farge delivered a second massive subvention amounting to 3.2 million francs to be used for Dalloz’s Plan Montagnards alone. And on 26 February Moulin’s deputy sent a coded message to London containing his budget proposals for March 1943. This amounted to a request for no less than 13.4 million francs for all the elements of the Resistance controlled by de Gaulle, of which some 1.75 million francs per month was designated for the Vercors. This was in addition to the private donations pouring into Aimé Pupin’s coffers by way of a false account in the name of a local beekeeper, ‘François Tirard’, at the Banque Populaire branch in Villard. This level of support made the Vercors by far the biggest single Resistance project being funded by London at this point in the war.

Despite these significant sums, money remained an ever-present problem for those administering the Vercors camps through 1943 and into the following year. A British officer sent on a mission to assess the strength and nature of the Maquis in south-eastern France visited the Vercors later in 1943 and reported that those in the camps ‘have to spend much of their time getting food etc. They have to do everything on their own and are often short of money. In one case they stole tobacco and sold it back onto the Black Market to get money.’

Not surprisingly this kind of behaviour, though by no means common, caused tensions between the réfractaires and local inhabitants. With food so short, the proximity of groups of hungry young men to passing flocks of sheep proved to be an especially explosive flash-point. On 14 June 1943, the réfractaires of Camp C4, fleeing to avoid a raid on their camp by Italian Alpine troops, arrived on the wide mountain pasture of Darbonouse where they were met by a flock of sheep numbering some 1,500. Their commander told them: ‘If there is any thieving I will take the strongest measures against the perpetrators. Remember that it is in our interests to make the shepherds our friends. Remember too that it is through our behaviour that the Resistance is judged.’

On the other hand, not far away at the Pré Rateau mountain hut above Saint-Agnan, another band of young réfractaires who had absconded from their original camp enjoyed a merry summer of pilfering and theft, to the particular detriment of the flocks of sheep in the area.

Tensions between local farmers were considerably eased when spring turned into summer and some camp commanders offered their young men as free labour to cut and turn grass and bring in the harvest. It was very common during the summer days of 1943 to see small armies of fit and bronzed young men among the peasant families in the fields and pastures of the Vercors. The easy habits of city living were being replaced by the calloused hands and sinewed bodies necessary for survival as a Maquisard.

This was not so everywhere. There was considerable variation between camps according to how and by whom they were run. By the middle of 1943, many camps had ex-military commanders and were run on military lines. Here, by and large, there was good order, effective security, discipline and good relations with the locals. In other camps, however, things had ‘the appearance of a holiday camp [with] young men taking their siestas in the shade of the firs after lunch or lying out in the sun improving their tans’.

One feature dominated the daily routine of all the camps, whether well run or not – the routine of the corvées, or camp chores. There were corvées for almost everything from peeling potatoes to gathering water (which in some camps had to be carried long distances from the nearest spring), bringing in the food, collecting the mail, chopping and carrying the wood (especially in winter), cooking, washing up and much else besides. Some camps – the lucky ones – were able to use mules for the heavy carrying, but many relied for their victuals, warmth and water on the strong legs and sturdy backs of their young occupants alone.

Soon it was realized that work in the fields was not going to be enough to keep the minds of intelligent young men occupied – or prepare them for what everyone knew would come in due course. One of the organizations established by the Vichy government – and then dissolved shortly after the German invasion of the south – was a school to train ‘cadres’ or young professionals to run Vichy government structures. The École d’Uriage, many of whose students came from the Army, was located some 15 kilometres outside Grenoble. Following the lead of its commander, the École soon became a hotbed of Resistant sentiment. When the École d’Uriage was dissolved in December 1943, most of the students and staff swiftly reassembled in the old château of Murinais, just under the western rim of the Vercors. It was from here, at the suggestion of Alain Le Ray, who had by now become the effective military commander of all the camps, that flying squads, usually of three or four students and staff, were sent out to the camps to provide training for the réfractaires. Typically a Uriage flying squad would spend several days in a camp, following a set training programme which provided military training, cultural awareness and political education. The curriculum included instruction in basic military skills, training exercises, weapon handling, physical exercise, map reading and orientation, security, camp discipline, hygiene and political studies covering the tenets of the Gaullist Resistance movement and a briefing on the aims of the Allies and the current status of the war. One camp even received instruction in Morse code. In the evenings there were boisterous games and the singing of patriotic songs around the campfire. Study circles were established which continued to meet after the flying squad had moved on. In many cases camp members were required to sign the Charter of the Maquis, which laid out the duties and conduct expected of a Maquisard. The Uriage teams even produced a small booklet on how to be a Resistance fighter with a front cover claiming it was an instruction manual for the French Army.

There was also some less conventional training given by one of the Vercors’ most unusual and remarkable characters. Fabien Rey was famous on the plateau before the war as a poacher, a frequenter of the shadowy spaces beyond the law, an initiate into the mysteries of the Vercors’ forests and hidden caves and an intimate of the secret lives of all its creatures. During the summer and autumn months of 1943, when not striding from camp to camp to share his knowledge with the young men from the cities, his latest crop of trapped foxes swinging from his belt, he could always be found sitting in his cabin invigilating a bubbling stew of strange delicacies such as the intestines of wild boars and the feathered heads of eagles, which he would press on any unwary visitor who passed. He also wrote a small cyclostyled handbook on how to live off the land on the plateau. It too was widely distributed and eagerly read.

In February 1943, Yves Farge, who had by now become the chief intermediary between Jean Moulin, de Gaulle’s emissary, and the Vercors Resistants, made the connection between Pierre Dalloz and Aimé Pupin’s organization. From now on, the two organizations, which were soon joined by their military co-conspirators, were fused into a single Combat Committee which directed all Resistance activity on the plateau.

On 1 March 1943, at a meeting in the Café de la Rotonde, Yves Farge handed Aimé Pupin the first tranche of the money London had sent by parachute to pay for the camps. Farge stayed the following night with Pupin and then, on the morning of 3 March, the two men set off on a day’s reconnaissance of the southern half of the plateau in a taxi driven by a sympathizer. They went first to La Grande Vigne to collect Pierre Dalloz and then continued their journey up the mountain to Villard-de-Lans, where they collected Léon Martin. From there the little group pressed on to Vassieux: ‘What I saw in front of me was the wide even plain around Vassieux … The aerial approaches to the plain from both north and south were unencumbered by hills, especially to the south. Somehow I had known that we would find an airstrip and here it was – and even better than I could have dreamed of … all around were wide areas which appeared specially designed to receive battalions parachuted from the sky.’

The little group stopped for a drink in a small bistro in Vassieux, pretending that they were looking to buy a piece of land on which to construct a saw-mill. But according to Dalloz, no one in Vassieux was deceived and the whole town, from that day onwards, believed that General de Gaulle himself was about to descend from the sky at any moment. The impression that secrets were impossible on the Vercors was further reinforced at lunch when, despite their attempts to appear discreet, the waiter at the Hôtel Bellier in La Chapelle announced their entry into the hotel dining room with the words ‘Ah! Here are the gentlemen of the Resistance.’

That afternoon, the party returned to Villard where they dropped off Léon Martin before taking a quick detour to look at Méaudre and Autrans in the next-door valley. Crossing back over the Col de la Croix Perrin, they were surprised to see Léon Martin standing in the middle of the road flagging them down urgently. It was bad news. The Italians had raided the Café de la Rotonde and arrested Pupin’s wife and fourteen other core members of the Grenoble organization.

Pupin immediately went to ground in Villard but not before taking two precautions. He dispatched Fabien Rey to Ambel to tell the réfractaires to decamp until the coast was clear. And he sent a friend down to Grenoble to try to prevent his records from falling into the hands of the Italians (whose soldiers had often frequented La Rotonde). He needn’t have bothered. The quick-witted Mme Pupin had burnt the records before they could be found. In the absence of any evidence, the Italians had to release all the detainees a few days later.

Aimé Pupin and his co-conspirators should have realized that they had been given two warnings that day. First that their activities were no longer secret. And second that keeping centralized records was dangerous folly. Sadly neither warning was heeded.

7

EXPECTATION, NOMADISATION AND DECAPITATION

Flight Lieutenant John Bridger, DFC, throttled down and watched the needle on his Lysander’s air-speed indicator drop back. Almost immediately the little aircraft’s nose dipped towards the three dots of light laid out ahead like an elongated ‘L’, the long stroke pointing towards him and the short one at the far end pointing to the right.

Bridger was one of the most experienced pilots in RAF’s 161 Lysander Squadron. On a previous occasion he had burst a tyre while landing Resistance agents at a clandestine strip deep in France. Worried that, with one tyre out, his Lysander (they were known affectionately as ‘Lizzies’) would be unbalanced for take-off, he pulled out his Colt automatic, shot five holes in the remaining good tyre, loaded up his return passengers for the UK and took off on his wheel rims.

Maybe it was because of his experience that he had been chosen for Operation Sirène II. Tonight, 19 March 1943, he was carrying passengers of special importance – Charles de Gaulle’s personal representative in France, Jean Moulin, the Secret Army’s commander General Charles Delestraint and one other Resistance agent. In truth, with three passengers on board, the little plane was overloaded for it was designed to take only two. But 161 Squadron pilots were used to pushing the limits.

Bridger’s destination this night was a flat field close to a canal a kilometre east of the village of Melay, which lies in the Saône-et-Loire valley 310 kilometres south-east of Paris and 700 from 161 Squadron’s base at Tangmere on the English south coast. This meant a round trip in his unarmed Lysander of some 1,500 kilometres, most of which would be flying alone over enemy-occupied territory. With a cruising speed of 275 kilometres per hour and allowing for headwinds and turn-around time on the ground, Bridger would be flying single handed for the best part of seven unbroken hours.

Like all of the RAF’s clandestine landings and parachute drops into France, tonight’s operation was taking place in the ‘moon period’ – roughly speaking the ten nights either side of the full moon (sometimes known by the codeword Charlotte). The remaining ten nights of the month were known as the ‘no moon period’ when conditions were too dark for accurate parachuting or safe landings. The March 1943 full moon occurred two days after Bridger’s flight, which meant that the moon’s luminosity this night was 91 per cent of that of the full moon, enabling Bridger to see many of the main topographical features such as woods and towns of the area he would be flying over. Most visible of all would have been the great rivers of France, which were 161 Squadron’s favourite navigational aids.

According to his logbook Bridger took off from 161 Squadron’s base at RAF Tangmere at 22.44 hours, two and a half hours after sunset that day. His post-operational report of his route is laconic and sparse on detail: ‘went via St Aubin-sur-Mer, Bourges, Moulins and direct to target. Apart from meeting a medium sized [enemy] aircraft 4 miles north of Moulin … the journey was uneventful.’

At Moulins, Bridger would have turned due east to pick up the River Loire, now turned by the gibbous moon into a great ribbon of silver, its little lakes and tributaries appearing as sprinkles of tinsel scattered across the darkened countryside. Here he swung south on the last leg of his journey – a lonely dot hidden in the vast expanse of the night sky. It is not difficult to imagine Jean Moulin and Charles Delestraint looking down on the moon-soaked fields and villages of occupied France and wondering about the task ahead and what it would take to free their country from the merciless grip of its occupiers.

The reception team waiting for Bridger at Melay that night was commanded by forty-year-old Pierre Delay, an experienced operator who had already received the Croix de Guerre from de Gaulle for his conduct of a previous SOE landing. He had been alerted that there was to be a landing on this site by a special code phrase broadcast during the six-minute ‘Messages personnels’ section of the BBC’s Les Français parlent aux Français. Delay had chosen Melay for tonight’s operation because he had a cousin who had a safe house 2 kilometres north of the landing site where the new arrivals could be put up, and a sympathetic local garage owner, whose Citroën was always available on these occasions.

According to Bridger’s operational report he ‘Reached target at 0140, signals given clearly & flare path good’. Delay’s men, who had waited in the deepening cold for two hours before Bridger arrived, now watched as the plane – it seemed big to them now – glided in almost noiselessly to touch down on the dewy grass. Moulin and Delestraint were bundled into the waiting Citroën and spent the night in the safe house, leaving the following day for Macon. They had arrived back in France to take command of a Resistance movement which was in a high state of expectation that the Allied landings would take place some time during the summer of 1943.

An SOE paper marked ‘MOST SECRET’ and dated 13 March 1943, just a week before the return of Moulin and Delestraint, discussed the possible uses of the Resistance in the event of an Allied landing, but warned that ‘the state of feeling in France has, after a gradual rise in temperature, suddenly reached fever pitch … there is a real danger that, if this … is allowed to pass unregarded, the French population … will subside into apathy and despair’. On 18 March, the night before Moulin and Delestraint landed, Maurice Schumann – who was for many the voice of Free France broadcasting on the BBC – was so inspired by news of the flood of réfractaires to the Haute-Savoie that he invoked the famous French Revolutionary force, the Légion des Montagnes, in one of his famous broadcasts, implying a Savoyard uprising. He was immediately rebuked by his London superiors for being premature – but he had accurately caught the feverish mood of excitement and expectation.

On 23 March, just three days after he arrived, Jean Moulin sent a coded telegram to London saying that the mood was so ‘keyed up’ that he had been ‘obliged to calm down the [Resistance] leaders who believe that Allied action was imminent’. One local Resistance leader, however, was sure that the state of over-excitement was generated not in France, but in London: ‘not a single one of us at the time was expecting an imminent landing. The truth was that the “over-excitement” of the [local] leaders reflected our intense preoccupation with the drama that was unfolding as a result of having Maquis organizations [in the field] without any support and our irritation over the attitude of de Gaulle and [the French] clandestine services.’

De Gaulle’s personal instructions to Delestraint before his departure, a copy of which can still be found in the French military archives in the Château de Vincennes in Paris, also give the impression that D-Day is fast approaching. Under the heading of ‘immediate actions’ to be taken ‘In the present period, before the Allied landings’, he instructed Delestraint to ‘prepare the Secret Army for the role it is to play in the liberation of territory’, including the ‘delicate measures necessary to permit a general rising of volunteers after D-Day [referred to by the French as ‘Jour J’] in the zones where this can be sustained because of the difficulty the Germans have in dominating the area’ – a clear reference, it would seem, to Plan Montagnards and the Vercors.

Whatever the true cause of all this premature excitement, the Vercors was not immune from its effects. Aimé Pupin commented that in the camps on the plateau the Allied landings were expected daily and ‘They were all burning for action …’ Unfortunately it was not just the Resistance who were ‘burning for action’ in anticipation of an Allied landing soon. France’s German and Italian occupiers were too.