Полная версия

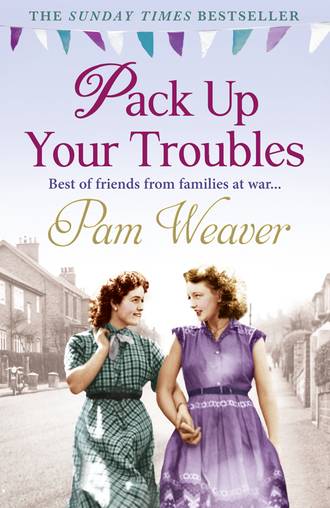

Pack Up Your Troubles

The back door slammed as she left the room. ‘No rest for the wicked,’ Gwen sighed good-naturedly.

At the weekend, the pattern of life at home was slightly different. The shop closed at noon on Saturday and normally on Sunday the whole family went to church in the morning. They were Anglicans but preferred to go to the Free Church which, because the war had interrupted their building programme, met in the local school. The services were bright and cheerful and it had a large Sunday school.

‘After Sunday school,’ Connie had told Mandy when she’d tucked her up the night before, ‘if you’re good, I’ll take you to see the gypsies.’

They ate their Sunday roast, and while Gwen sat with her knitting listening to the radio and Ga sat at her writing desk, Connie and Mandy and just about every other child in Worthing set off for Sunday school. In the main it was fun and the hour was precious to parents because it was the one time that they could have an hour to themselves with no interruptions. Pip went along with them but Connie made him wait outside. The class was held in a small room at the back of the church. The teacher, Miss Jackson, was a little older than Connie but they had both gone to the same school.

‘Connie!’ Jane Jackson, an attractive brunette, was now a librarian. ‘How good to see you. Are you back for good?’

‘Looks like it,’ Connie smiled.

‘We must get together sometime,’ Jane smiled. ‘No, William, stop hitting Eddie with that hymn book. That’s no way to behave in church.’

The children sat in a semi-circle on a large mat on the floor. There were about thirty of them in Jane’s class, nearly all of them the children of church members although there were a few who had been sent along by their parents so that they could have a bit of peace and quiet and a little time to themselves. They began with a prayer and then some choruses. Jane and her fellow teachers were ably assisted by Michael Cunningham, the son of the church treasurer, a pimply faced youth who was waiting to go to university. Michael hammered out the tune on the school piano.

The choruses brought back memories of her own childhood. They were as timeless and as meaningless as they had ever been. ‘Jesus wants me for a sunbeam …’ ‘Bumble bee, bumble bee, buzz, buzz, buzz, buzz, buzz …’ and ‘I am H-A-P-P-Y …’ The Bible story was based around the woman with the issue of blood. Connie wondered if five- to seven-year-olds had any idea what ‘an issue of blood’ meant, but she was surprised to see that the children listened enraptured. Apparently Jane was a gifted storyteller. One more chorus, this time one relating to the story itself, ‘Oh touch the hem of His garment and thou too shalt be whole …’ and Sunday school was over. At the end of the session, as they said their goodbyes, Jane produced a box of sweets. Each ‘good’ child, namely the ones who had sat still while they’d had the story, was allowed to take one. Connie permitted herself a wry smile. Clever old Jane. No wonder the children sat still and listened.

‘There’s a dance at the Assembly Rooms on Saturday,’ said Jane as they were leaving. ‘A few of us from the village are going. Sally Burndell comes. You know her, don’t you?’

‘She works part time in our shop,’ Connie nodded.

‘Do come to the dance,’ said Jane. ‘They’re great fun.’

A couple of days slipped by but at the earliest opportunity, Connie climbed upstairs to the attic with a torch. It was hot and musty but she’d only been there for about ten minutes before Gwen came to see what she was doing.

‘It’s chock-a-block up here, Mum!’ Connie gasped. ‘I had no idea we had all this junk.’

Her mother looked a little surprised too. ‘I suppose it’s years of saying, “Oh … put it in the attic for now”,’ she smiled. ‘What are you looking for anyway?’

‘My old school books,’ said Connie. ‘I’m teaching Kez to read.’

‘Try that box over there,’ said her mother.

The first of the boxes contained an old photograph album. Connie flicked through and smiled. The box Brownie had recorded so many happy occasions but it was a shock to see her father’s face again. Out of respect for her new husband, her mother had moved his pictures up here when Clifford came into the family. She turned a page and there was Kenneth. Her heart missed a beat and she sighed inwardly. He looked about twelve. He was bare-chested and wearing short trousers. His fair hair was tousled and he had obviously been looking for something in the pond. He was proudly holding up a jam jar tied with a string handle and something lurked in the water. She stared at her long lost brother and wished he was here. Memory is selective, she knew that. She’d forgotten the times when they had been at loggerheads, or the times when he’d thumped her for getting in his way. All she could recall were the picnics on the hill and her mother reading them endless stories, or fun and laughter at the beach and being pushed on the swings until she was so high it was scary. She ran her finger over Kenneth’s face and slipping the photograph from its stuck-down corners, she palmed it secretly into her pocket.

Her mother was rummaging through a different box. ‘These are all books,’ she said.

Putting the album down, Connie went to join her. Her mother had found an old school book but it looked very babyish. Connie didn’t want to embarrass Kez because she knew that she wouldn’t bother to practise if the book looked like it was for a child. In the end she chose two of her own books to take. Grace Darling’s Tales, a book she had been given by an aunt when she was about nine. It had two girls in swimsuits on the front cover. They were standing on the rocks with their dog. It was a bit more advanced than Connie would have liked but it was a start. The other book was her all-time favourite when she’d been a girl. She’d bought the Stories from the Arabian Nights for thruppence in a jumble sale. Connie knew she would enjoy hearing the stories again; The Porter and Ladies of Baghdad, Caliph the Fisherman and Ali Baba, who adorned the front cover. She’d always loved the romantic illustrations of the men in their flowing robes and dark smouldering looks. Now she and Kez could begin her long uphill journey to literacy.

As they pushed the box back against the wall, it was hindered by something underneath. Connie bent down and picked up a stuffed giraffe, Kenneth’s toy from when he was a baby. It was in a sorry state now, lopsided and some of the stuffing had come out of one foot. The two women stared at it in silence.

‘Do you ever think of him, Mum?’ Connie asked quietly.

Gwen straightened her back. ‘He is my son,’ she said simply. ‘There isn’t a day goes by when I don’t think about him.’

Connie could feel the tears picking at her eyes. She pushed the box right back and stuffed the giraffe down the side. That’s when she spotted her old doll’s pram. ‘Oh, look! I bet Mandy would like to play with that,’ she said deliberately changing the subject. She raised the hood and fingered the holes along the crease.

‘It could do with a bit of repair,’ said Gwen uncertainly.

‘And I know just the man,’ smiled Connie. ‘Don’t say anything and we’ll get it done for Christmas.’

Armed with her books, Connie made for the stairs. Her mother hesitated. ‘You don’t know why Kenneth left like that, do you?’

Connie froze. Her face flamed. She dared not look back or her mother would have seen. ‘Haven’t a clue,’ she said brightly as she ran down the stairs.

The nurse pulled the curtain around his bed and leaned over to undo the buttons on his pyjama top. Kenneth didn’t look down. He didn’t want to see the livid redness, the uneven skin and the scars. He’d looked at himself in the mirror once and it had turned his stomach. His own body and he couldn’t stand to look at it. They had done what they could and the ice packs on his hand relieved the awful pain. Hands. That was a joke. He didn’t have hands anymore. One of them was little more than a shapeless stump.

The doctor and his entourage swept in, each pulling the curtain closed until they were all cocooned together. Now there were six of them standing around his bed. Six and the nurse. Nobody spoke. He looked at each man in turn. He knew what they were thinking. Poor sod. Got right through the war unscathed and then, while the rest of the world is dancing in the streets, he comes down in flames to this … He thought of some of those who didn’t make it. Pongo Harris and Woody Slade and little Jimmy. At least they’d gone out intact. He might be still alive, but look at the state he was in. It would have been better if he’d died along with the rest of his crew.

The doctor leaned towards him. ‘I’m putting you up for transfer, Dickie,’ he said.

Kenneth snorted and turned away. That’s right, he thought. Out of sight, out of mind. Not my problem.

‘Listen, son,’ said the doctor. ‘We’ve done all we can for you here, but there’s a place where they are brilliant at helping boys in your position. It’s in East Grinstead, the Royal Victoria Hospital. They’ve got this man there called McIndoe and he’s pioneered some wonderful treatments for burn victims.’

‘The chaps who’ve been there are proud of what they’ve achieved. They called themselves The Guinea Pig Club,’ said one of the others.

Kenneth closed his eyes in disgust. ‘I’m not going somewhere to be experimented on. Just give me a gun and I’ll finish the job for good.’

‘That’s enough of that kind of talk,’ the doctor snapped. ‘Look,’ he added softening his tone, ‘what if I get someone to come and see you? Maybe even the big man himself. It’s up to you, but surely it’s worth a try.’

Kenneth sighed. He didn’t want this but they’d keep on and on until they had their way and he was too tired to argue. ‘All right,’ he said wearily.

‘Good man.’ The doctor leaned towards him again. ‘You know, it’s time you thought about contacting your loved ones.’

His patient’s eyes blazed. ‘No, absolutely not. I’m not ready for all that.’

Connie kept herself busy for the rest of the day and did her best to avoid working with her mother. After tea, Connie worked in the shop with Sally. They usually had a bit of a laugh together but Sally wasn’t her usual chatty self which suited Connie for now. Her mind was filled with thoughts of Kenneth. If all went to plan, she would join Kez in the evening and begin her lessons. Perhaps she should talk to Kez about Kenneth, and yet even as the thought crossed her mind she knew she wouldn’t. It was embarrassing and shameful and she couldn’t bear the thought of Kez knowing such awful things about her. She had struggled for years to put it all behind her, but what with Ga and her constant reminders and the fact that her brother was estranged from the family, what hope had she? At least by keeping busy, she wasn’t thinking about having to lie to her mother. How she wished she could just up sticks and go for her training. Being a nurse seemed to be so right for her but by being stuck here in the nursery, she’d probably end up like Ga, an old maid with nobody to love. Life was bloody unfair sometimes.

Five

It didn’t take long for Saturday evenings at the dance hall to become a routine. Connie joined up with Jane Jackson, Sally Burndell and a couple of other girls to go to the Assembly Hall in Worthing. Their dresses were all homemade. There was so little material to be had but Connie was good with a needle. She was wearing a pretty blue and white dress with a full skirt and a scooped neck with a trail of white muslin draped attractively across the shoulders. She’d found the material in another form in a jumble sale. The dress was far too big so she was able to take it to pieces and start again.

The dance was up some steps in the next road to the New Town Hall. The place was packed although as time went by, there were fewer men in uniform. Demob suits were very much in evidence. The Assembly Hall was a beautiful building. They entered a large foyer, bought their tickets and went to the cloakroom to hang up their coats. Connie loved the Art Deco reliefs, the star-shaped light fittings and the proscenium arch which was flanked by seahorses. It spoke of an age long since gone and yet somehow the building seemed as fresh and exciting as it must have done when it was built in the 1930s.

The band was already playing as they walked in and a small glass orb glittered from the ceiling. Connie and her friends found a table and sat down. The dances were done in threes. It might be a foxtrot or a rumba or a waltz when the lights were dimmed right down. As the band struck up, the men circled the seated area looking for a partner. Jane was always popular but Connie and Sally had to wait a little while before someone asked them to dance.

It had taken Connie a while before she’d got to know the other girls. At sixteen, Sally’s secretarial course was due to start towards the end of September. She may have been a lot younger than the rest of them, but she fitted into the group well. Jane was the joker. Having heard of Sally’s ambition to be a private secretary rather than ending up in the typing pool, Connie had asked Jane about her ambitions. Jane had looked thoughtful and then said, ‘I think I’ll marry a man with one foot in the grave and the other on a banana skin,’ and they’d all laughed.

‘How’s your boyfriend in the army?’ said Connie making small talk while they waited.

Sally had just refused to dance with a tall, lanky man with buck teeth. ‘Terry? Fine,’ she nodded. She picked up her handbag and rummaged inside. ‘He’s still in Germany. He says he’ll be stuck there until he’s demobbed next year.’

‘What rotten luck,’ said Connie. ‘A year is a long time.’

‘I’ll wait for him,’ said Sally, pulling out a dog-eared photograph. ‘That’s my Terry.’ He looked about twenty and was tall with round-rimmed glasses.

‘He doesn’t mind you coming to dances?’

‘Well, he can’t expect me to live like a hermit,’ Sally retorted, ‘but I shall always be faithful to him.’

A good looking man with slicked-down hair came up to the table and gave the girls a short bow. ‘May I?’

‘And what the eye doesn’t see …’ said Sally, taking his hand.

Connie went back to the gypsy camp whenever she had a spare minute. Kez was a willing pupil even though some of her relatives teased her when they saw what she was doing. She had been right about the books. Kez had loved the Stories from the Arabian Nights and who could blame her. All those handsome, dark-eyed men fighting for the women they loved and looking at the girls in their pretty Eastern dress made enjoyable reading.

‘The way you two sit like that,’ Reuben remarked one day, ‘you could be sisters.’

Connie smiled. She would have liked to have had a sister like Kez. Simeon was a nice man too. He sat close to his wife and a couple of times, as Connie traced the words with her finger on the page, she caught him mouthing the words along with her. So he was illiterate too? Connie was amazed. He had created a real work of art in wood on the outside of the trailer. He clearly had a good eye because the few times she had watched him at work, she’d noticed that he didn’t have a pattern to follow. It was all in his head. Eventually Connie plucked up enough courage to ask him about the pram.

‘Bring it with you next time,’ Simeon smiled, ‘and I’ll see what I can do.’

People labelled gypsies as stupid but Kez and her family were far from that. They may have lacked formal education but their skills and knowledge in other areas were second to none. Isaac was always turning up with a river fish or a couple of rabbits, and at one time a couple of pigeons for their supper. Kez invited Connie to stay but most times she declined, preferring to be home in time to read Mandy a bedtime story.

When Connie got back home on 24 July, her mother and Ga were glued to the radio. At the beginning of the month the whole country had been full of election fever. Most people thought it a foregone conclusion that Mr Churchill would get back into Downing Street but there was also a groundswell of opinion that the country couldn’t go back to the old ways. It was time for radical change. All the same it came as an enormous shock when the final count was declared after the overseas votes had been collected by RAF Transport Command. The Labour Party headed by a rather weedy looking man called Clement Attlee had won a landslide victory.

‘God help us all,’ Ga said darkly as she turned the radio off. ‘It’s going to be just like Churchill said. We beat the Gestapo in Germany and now they’ll come here, you mark my words.’

‘I’m sure it won’t be that bad, Ga,’ said Gwen good-naturedly.

‘And you can hardly blame us for wanting change,’ said Connie tartly. ‘Look what’s on offer, full employment and a free health service.’

‘Stuff and nonsense,’ Ga retorted. ‘Anyone with half a brain could see that’s all rhetoric and empty promises. A welfare state from the cradle to the grave? It’ll never happen in my lifetime.’

It had taken a bit longer than they’d thought but Clifford came home with the minimum of fuss. Connie and her mother were anxious about him because they had no idea what kind of state he might be in. Immediately after the war, the newsreels at the pictures showed some harrowing sights coming out of Germany. Whole cities flattened by Allied bombing, women and children picking their way through the ruins and of course the opening up of those terrible concentration camps. It was a lot to take in and it must have been even worse for those who saw it at first hand. Joan Hill from the village found a wreck of a man waiting on the platform when her Charlie came home and he still wasn’t right in the head.

Clifford was due to come back on a Saturday and so Connie took Mandy out for the day in order to give her mother a little space. They went to Arundel on the bus and on to Swanbourne Lake. Pip invited himself too and had been as good as gold on the bus, lying by their feet until it was time to get out. Mandy fed the ducks with some crusts of bread and then they walked right around the lake. Pip loved it. He didn’t chase a single duck but enjoyed his freedom to scent and smell as he pleased. They stayed until late afternoon and Connie treated them to tea in a little tea rooms while Pip lay on the pavement outside and waited for them.

As it turned out, Clifford had come through his experiences with little evidence of trauma. A clean shaven man with a strong jawline and firm resolve, he looked a little too small for his demob suit but he was still good looking enough to cut a dash. His Brylcreemed brown hair had retained its colour although there were a few grey hairs at either side of his ears. When he spotted Connie and Mandy walking up the road, he ran to meet them, and catching Mandy into the air he swung her up. Pip barked and jumped at his legs and Connie laughed. Clifford’s daughter was a little more reserved in her greeting and wriggling out of his arms, as soon as he put her down she ran and hid behind Connie’s skirts.

‘She’ll be all right,’ Connie whispered when she saw the look of disappointment on his face. ‘Just give her time.’

Clifford put his hand lightly on her shoulder and kissed Connie on the cheek. ‘Is it good to be back?’ she asked.

Her mother was standing by the front door, looking on. ‘I’ll say,’ he smiled, adding out of the corner of his mouth, ‘although your mother looks a bit pasty.’

‘I’ve tried to persuade her to go to Dr Andrews,’ Connie whispered as she smiled brightly, ‘but she won’t go.’

‘I’ll get her to make an appointment as soon as I can,’ he said as they turned to walk back to the nurseries.

‘She probably won’t tell you,’ Connie said while they were still far enough away from the door to be out of earshot, ‘but I’ve offered to look after Mandy if you want to go away for a holiday.’

‘Can I go on holiday too?’ Mandy piped up.

‘Oh my, what big ears you have,’ laughed Connie and Clifford ruffled Mandy’s hair.

‘Was Ga all right with you?’ Connie asked as her sister skipped up the garden path.

‘Same as usual,’ said Clifford grimly. ‘I swear that woman looks more miserable than Queen Victoria with every passing year.’

Connie put her hand over her mouth to stifle a giggle.

The rest of the weekend was good because everyone was on their best behaviour. Clifford insisted her mother go to the doctor on Monday. A touch of anaemia, that’s all it was, and she was prescribed a tonic. ‘Take a rest if you can,’ he advised and so Clifford went ahead with his plans for them to go to Eastbourne for a few days.

A week went by and slowly the family readjusted itself back into some sort of normality. Aunt Aggie turned up as usual and although she probed Clifford with questions, thankfully she wasn’t too intrusive. It was obvious that he didn’t want to talk about his experiences. He’d lost too many friends and three years of his life. Ga continued making her barbed remarks, the worst being one day when the four of them were in the shop.

‘It’ll be hard for you to settle down,’ Ga told Clifford. She was smiling but her eyes were bright with insincerity. ‘No pretty girls throwing themselves at the liberators here.’

‘Ga!’ said Connie, shocked.

‘Don’t tell me he didn’t enjoy the attention,’ Ga went on. ‘Sailors have a girl in every port so I don’t suppose the army is much different?’

‘Not everybody is sex mad, Miss Dixon.’

They turned to look at Sally who was clearing overripe fruit from the display. They’d all forgotten she was there. Sally straightened up and blushed deeply, realising at once that she had overstepped the mark and been too familiar with her employers.

‘And I’ll thank you to keep your nose out of other people’s conversations, Sally,’ said Ga haughtily. The girl turned back to her work and said no more.

Clifford walked away, the door banging against the wood as he left.

‘Pay no attention, dear,’ said Aggie when she saw the crestfallen look on her friend’s face.

‘Some people just can’t take a joke,’ said Ga.

As Connie walked with Mandy to the gypsy camp the day after her mother and Clifford had gone away, she already felt more relaxed. She might not have met anyone at the dance, but each week she’d had a bit of fun, something singularly lacking in her life up to now. It was incredible that Kez and her family had spent so long in the lane and there was always that sinking feeling that they might be gone when she turned the corner.

‘Susan Revel says gypsies are smelly and shouldn’t be allowed here,’ said Mandy, taking Connie’s hand as they came to the lane. Pip came bounding along to join them. ‘She said they steal people’s babies and turn them to stone.’

‘Does she now?’ said Connie.

‘And Gary Philips says they are short in the arm and thick in the head.’

Connie suppressed a smile. ‘If I were you, I wouldn’t repeat what someone else says,’ she said gently. ‘I’ll tell you what, after we’ve been there, you tell me what you think.’

Mandy nodded gravely. ‘Can I share my sweeties with Sam?’

So that was why Connie had seen her squirrelling away a couple of farthing chews from her sweetie box. Mandy hadn’t asked if she could have one but Connie hadn’t said anything. Why not let her have them? They were her sweets after all. She had no idea Mandy was planning to share them with Kezia’s son. ‘I’m sure he’d love that,’ said Connie, ‘but ask his mummy first.’

Somewhere along the lane, Pip joined them again. ‘Where have you been?’ said Connie, patting his side.

The two sisters were very close. Connie adored Mandy and it was plain to see that Mandy enjoyed being with her. Kez took to her straight away especially when Mandy began to mother little Samuel.

The women spent the rest of the afternoon rubbing down handmade clothes pegs and putting them into bundles. On Monday, Kez and some of the other women would take them around the big houses in Goring and sell them. As they worked, Pen told them tales about the old days … ‘Little Mac took the tattooed lady’s mare then Abe gave Little Mac a piece of bread and a quart of ale but there was none for ’e so he died …’ Mandy listened spellbound and for Connie it felt just like old times. Peninnah always used the same form of words and if anyone interrupted her, she’d go back a bit and start again.