Полная версия

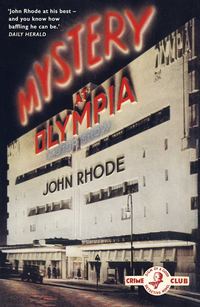

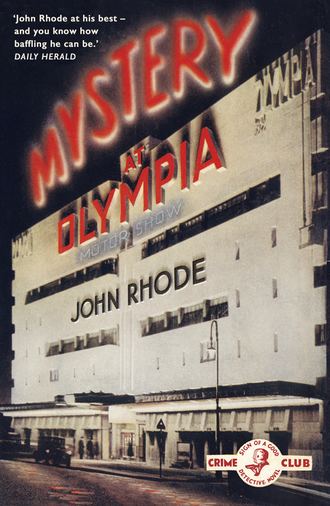

Mystery at Olympia

That evening, soon after ten, when the last of the public had been shepherded from the hall, and the exhausted staffs were clearing up for the night, the sales manager of the Solent Motor Car Company was fussing about his stand. He was not in the best of tempers. Solent and Comet cars were in much the same class, and an intense rivalry had always existed between them.

As it happened, the Solent people had made very few alterations to their models for this particular year, with the result that there was nothing startlingly novel exhibited on their stand. Since novelty is what attracts a very large percentage of visitors to the show, this had resulted in comparatively few inquiries. And yet the Solent stand, number 1276, was very favourably placed to attract notice. It was close to the entrance, almost the first thing to catch the visitor’s eyes as he entered the building.

The sales manager had a definite sense of grievance against his directors. If they hadn’t been such a sleepy lot of fatheads, they would have seen to it that the works got out something new, and not left it to the Comet people to steal a march on them like this. How the devil could a fellow be expected to sell cars to people if he had nothing out-of-the-way to show them?

He happened to glance through the window of a resplendent Solent saloon, and something lying on the floor at the back caught his eye. He opened the door, and picked up a mushroom-shaped piece of steel. ‘What the devil’s this?’ he exclaimed, frowning at the unfamiliar object.

One of his assistants, standing near by, answered him. ‘It looks like one of the exhibits from the Comet stand,’ he said.

‘What? One of those people’s ridiculous gadgets? How do you know that?’

The assistant, realising that he had given himself away, looked uncomfortable. ‘Well, I just took a stroll round their stand in my lunch hour,’ he replied sheepishly.

‘Oh, you did, did you? And I suppose you’ve been recommending people who come here to look at our stuff to follow your example. And how did this damn thing get on our stand? Perhaps you brought it back with you as a souvenir?’

The assistant attempted the mild answer which turneth away wrath. ‘I didn’t do that. But I’ll take it back to the Comet stand, if you like.’

‘Take it back? Let them come and fetch it if they want to. I’d have you know that employees of our firm aren’t paid to run errands for the Comet people. And see that you’re here sharp at nine tomorrow morning. I want some alterations made on this stand before the show opens.’ And, without vouchsafing a good-night, the sales manager departed.

His assistant watched him leave the hall. Then, since he had a friend in the Comet firm, he picked up the pressure valve, for such it was, and carried it to stand 1001. There he encountered the demonstrator who had been holding forth when Mr Pershore collapsed. ‘Hallo, George, this is a bit of your property, isn’t it?’ he said.

George Sulgrave recognised the pressure valve at once. ‘Where did you get that from, Henry?’ he asked suspiciously.

‘My Great White Chief found it inside one of the cars on our stand. Somebody must have picked it up, and then, finding it a bit heavy to carry about, put it down in the most convenient place.’

Sulgrave glanced round the stand. There was certainly a gap in the row of gadgets which bordered it. ‘Yes, that’s right,’ he said. ‘Some of these blokes would pinch the cars from under our very noses, if they thought they could get away with them. Thanks very much, Harry. We shall have to have these things chained to the floor, or something like that. How’s business on your stand?’

‘Simply can’t compete with the orders we’re getting,’ Harry lied readily. Loyalty to one’s firm is a greater virtue than truthfulness to one’s friend, as Sulgrave would have been the first to agree. ‘We’ve sold all our output for next year already.’

‘Same here,’ replied Sulgrave, no more truthfully than Harry. ‘You must come down and look us up when this confounded show is over. Irene will be glad to see you.’

‘Thanks very much. I’d like to run down one evening. Good-night, George.’

‘Good-night, Harry. Much obliged to you for your trouble.’

The attendants on the various stands completed their labours and went home. An almost uncanny hush settled upon the vast and now dimly lighted expanse of Olympia. Wrapped in a similar hush, and an even dimmer light, the body of Mr Nahum Pershore lay on a slab in the mortuary, rigid and motionless.

CHAPTER II

Mr Nahum Pershore had purchased all that messuage and tenement known as Firlands, Weybridge, some five years before his death. He had got it cheap, since, as the agent who had sold him the place had observed, it wasn’t everybody’s house.

This was quite true. Firlands was an outstanding example of the worst type of Victorian domestic architecture. One felt that the designer’s aim had been to achieve the maximum of pretentiousness without, and discomfort within. Still, nobody could deny that the house was ostentatious, and Mr Pershore liked ostentation. Besides, as Mr Pershore, who had amassed a considerable fortune by speculative building, could see at a glance, the house was solidly built and in excellent repair.

Mr Pershore was a bachelor, and he brought with him to Firlands his housekeeper, Mrs Markle. Long ago, fifty years at least, Nahum Pershore and Nancy Beard had played together in the builder’s yard belonging to Nahum’s father. They had grown up together, and perhaps, but for a series of events which had long ago lost their importance, they might have married. But, somehow, Nancy had drifted into matrimony with the son of Mr Markle, who kept the tobacconist’s shop over the way.

Nahum had risen in the world, thanks to a certain pertinacity and acumen. Nancy had not. After twenty years of married life, during which she had encountered many vicissitudes, she found herself a childless widow with nothing but her wits to support her. For a time she eked out an existence by obliging one or two families in the neighbourhood. In fact, she had achieved the status of a charwoman. And then one day, casting about for something more lucrative and less exacting, she thought of her old companion Nahum Pershore. She sat down and wrote him a letter. It was indicative of the gulf which had opened between them that in this she addressed him as ‘Dear Sir.’

Had she been inspired with some form of second sight, she could not have posted the letter at a more favourable moment. Mr Pershore was suffering from a profound weariness of housekeepers. They had come and gone, each more unsatisfactory than the last. Some had been young, and these had displayed tendencies which seriously alarmed the bachelor instincts of their employer. Others had been old, and these had been incompetent, and allowed the servants to do what they liked with them. He had just terminated the unpleasant business of giving notice to the last of them, when Mrs Markle’s letter arrived.

Nancy Beard, or Nancy Markle, as she was now! He hadn’t given her a thought for years. But he remembered her perfectly, both as a child, when they had been such good friends, and later, as a tall, lanky girl of nineteen. Tall she had been, certainly. Taller than he was himself. It may have been, though the thought did not occur to Mr Pershore, that that was why he had never married her. Or it might have been her ungainliness, or the lack of her pretensions to any sort of beauty. Mr Pershore, looking back, wondered what that thin-faced chap Markle could have seen in her.

Could he put Nancy Markle in the way of finding a job? That was the gist of her letter. Well, perhaps he might. She was within a year of his own age, neither too young nor too old. She had always been a dutiful daughter before her marriage, helping her mother in the house, instead of gadding about as so many of them did. It seemed quite likely that she would make him an excellent housekeeper. But …

It was this doubt that caused Mr Pershore to hesitate. He had only to shut his eyes to recall vivid pictures of himself and Nancy walking home from school together, or sitting with their arms round one another on a pile of timber in his father’s yard. Had Nancy retained the same vivid recollections, and, if so, how would this affect their future relations? He looked at the letter once more, and the inscription ‘Dear Sir’ reassured him. He wrote to her, asking her to come and see him.

His misgivings evaporated at the interview which ensued. Whatever memories Nancy Markle may have had, she kept them strictly to herself. Her experiences and her present condition were in such striking contrast to those of her former playmate that, in her eyes, they now moved in wholly different spheres. From the moment of their meeting again, their relative positions were established. Mr Pershore was the master, Mrs Markle was willing and obedient servant. It was as though the very knowledge of one another’s Christian names had been erased from their minds. Before the interview terminated, Mrs Markle had been definitely engaged as Mr Pershore’s housekeeper.

That had been ten years earlier. Mrs Markle was now a tall, gaunt, loose-limbed woman with wisps of iron-grey hair. But she had turned out a perfect housekeeper. Mr Pershore very rarely so much as saw her. The smoothness of the running of his household, however, was ample proof of her efficiency behind the scenes. Mr Pershore allowed her a perfectly free hand in everything which concerned his domestic arrangements. Such matters as the engagement of servants were her province alone. Of these a staff of four was employed at Firlands. Cook, parlourmaid, housemaid and kitchenmaid. The garden was the care of a jobbing gardener, who came three times a week.

Under Mrs Markle’s rule the domestic routine was regular, but not too exacting. Breakfast was served in the servants’ hall at eight o’clock, and in the dining-room and housekeeper’s room simultaneously at a quarter to nine. Lunch, if Mr Pershore happened to be at home during the day, or if visitors were staying in the house, was at a quarter past one. Mrs Markle, who was a very small eater, did not lunch. She preferred to make herself a cup of tea, with a slice or two of bread and butter, in the housekeeper’s room, at any time she happened to fancy it. Dinner was served at eight, and supper, in the servants’ hall and housekeeper’s room, at nine.

On the day of his death Mr Pershore had left home, as was his custom three or four days a week, about ten o’clock. Mrs Markle spent the morning supervising the work of the household—she was by no means above taking a hand herself, if any of the servants had more than their usual share of work—and telephoning orders to the tradesmen. There were no visitors staying in the house, and Mr Pershore had announced his intention of not being home until the evening. By one o’clock Mrs Markle had finished her morning’s work, and was sitting in her own most comfortable room. She contemplated spending a nice quiet afternoon with her sewing.

But her peaceful occupation was rudely disturbed by the sound of running footsteps, and an imperious knocking at the door. Before she had time to say ‘Come in!’ the door burst open, and the cook projected herself into the room, and subsided into a chair, too breathless for speech.

Mrs Rugg had been cook at Firlands for the past three years. She was stout, and rather deaf, and Mrs Markle secretly suspected her of over-indulgence in gin on the occasions of her evenings out. But she was an excellent cook and thoroughly reliable. Never before had she been known to behave with such a lack of decorum.

For the moment Mrs Markle imagined that she had had recourse to some secret store of spirits. But, before she could make any remark, Mrs Rugg had recovered sufficient breath to gasp out her news. ‘Oh, Mrs Markle! It’s Jessie! She’s come over terrible bad! In the kitchen. Gave me such a turn!’

Mrs Markle rose, with a swift movement characteristic of her. Leaving Mrs Rugg gasping in her chair she hurried along the passage towards the kitchen. Jessie Twyford was the parlourmaid, a pretty girl, the daughter of the postman, on whose recommendation she had been engaged. Mrs Markle, in spite of her haste, found time to wonder what could be the matter with Jessie. She had been all right, barely an hour before, when Mrs Markle had helped her to give the dining-room an extra turn out. Certainly Mrs Markle had noticed nothing amiss then. Besides, the Twyfords were a highly respectable family. Could it be?

She reached the kitchen, with these dark suspicions still unresolved. And, at first glance, she could see that Jessie was in a very bad way. She had collapsed into a chair, out of which she seemed to be in danger of slipping every moment. She had been very sick, and a hoarse moaning sound escaped from her parched throat.

A cursory inspection satisfied Mrs Markle that her suspicions were unfounded. ‘Why, Jessie, whatever’s the matter?’ she asked, as she bent over the girl.

‘Oh, Mrs Markle, I’m going to die!’ Jessie replied despairingly, between her moans.

‘A strong girl like you doesn’t die as easily as all that,’ said Mrs Markle cheerfully. She beckoned to the kitchenmaid, a strapping wench, who was standing by helplessly, with eyes wide open in horror. ‘Take hold of her under the knees, Kate,’ she continued. ‘That’s right. We’ll carry her on to the sofa in the servants’ hall.’

Jessie wailed piteously as they lifted her, but she seemed a little more comfortable when she had been deposited on the sofa. ‘Now then, Kate, look sharp!’ said Mrs Markle. ‘Fill a couple of hot-water bottles, and put them on her stomach. Then see if she can drink a drop of water, while I go and telephone for Doctor Formby.’

She hurried away to the telephone. Doctor Formby, who lived a short distance away, and upon whose panel were all the members of the domestic staff at Firlands, was at lunch. On hearing Mrs Markle’s account of Jessie’s symptoms, he promised to come round at once.

Mrs Markle returned to her patient. Jessie was suffering from a parching thirst, but every mouthful of water she managed to take caused a return of her sickness. She complained of cramp in the limbs, and continually tossed about to obtain relief. Mrs Markle was doing her best to make her comfortable when Doctor Formby arrived.

He felt the girl’s pulse and looked at her tongue. Then he issued hurried instructions to Mrs Markle. Between them, they managed to wash out the remaining contents of the girl’s stomach. Then Doctor Formby gave her an injection, and watched her until it had taken effect. He turned to Mrs Markle. ‘She’s been sick, you say?’ he asked.

‘Terrible sick, doctor,’ the housekeeper replied. ‘All over the kitchen floor.’

‘Well, don’t let them clear it up just yet. I shall want a specimen. Have you got any weed-killer in the house?’

‘Weed-killer! No, there’s none in the house. Bulstrode, that does the garden, may have some in the potting-shed. But I could easily send one of the girls into the town to buy some, if you’re wanting it.’

‘No, I don’t want it,’ replied Doctor Formby slowly. He wondered if it were safe to confide in Mrs Markle, and decided that it was. He knew her as a sensible woman, who could hold her tongue, and was not in the habit of becoming panic-stricken. ‘I asked if you had any weed-killer in the house because I wondered whether Jessie could have taken any,’ he continued. ‘I don’t want you to say anything to anybody else, Mrs Markle. But, between ourselves, this looks to me very like a case of acute arsenical poisoning.’

Mrs Markle gave him a horrified glance. ‘Arsenic!’ she exclaimed. ‘There’s never been anything like that in the house, to my knowledge.’

‘I can’t be certain, until I’ve had time to make a test,’ replied Doctor Formby. ‘But it’s only fair to warn you that I’m pretty sure of it. The point is, where did the stuff come from? She hasn’t seemed depressed or anything lately, has she?’

‘Jessie? Why, she’s the most cheerful girl I’ve ever had to do with. Always laughing and singing about the place.’

‘None of the other girls got a grudge against her, by any chance?’

Mrs Markle shook her head decidedly. ‘Everybody who knows Jessie likes her,’ she replied.

‘Well, she must have taken it accidentally. Don’t let any of the others have any dinner. It won’t do them any harm to starve for a few hours. And try to find out what she’s had to eat today. I shall stay with her for the present, till I see how things go.’

Mrs Markle went off to find the cook, whom she questioned closely. Jessie had had the same breakfast as the rest, none of whom had felt any ill effects. She had had a cup of tea at eleven, from a teapot which Mrs Rugg herself had shared with her. ‘And apart from that, she’s had nothing from my larder,’ concluded the cook with conviction.

The housekeeper went up to Jessie’s room and searched it diligently. She found nothing whatever to eat or drink, not even a biscuit or a packet of sweets. Then she returned to the servants’ hall, and made her report to Doctor Formby.

‘Well, it’s very queer,’ said the doctor. ‘Stay with her for a minute or two, will you, Mrs Markle? I’ll go and collect my specimen, and then the mess can be cleared up.’

He returned with a sealed jar, which he put in his bag. Then he resumed his vigil by the sofa, holding the unconscious girl’s wrist. Not until half-past three did he pronounce his verdict. ‘She’ll pull through now, I think,’ he said. ‘She’d better not be moved for the present, but keep her as warm as you can. I’ll send a nurse round, and come round myself in a few hours’ time.’ He paused, and looked fixedly at Mrs Markle. ‘I’m going back home now to test this specimen. You realise that if the test confirms the presence of arsenic, I shall have to inform the police?’

Mrs Markle bowed her grey head silently. The idea of the police had been in her mind ever since the ominous word arsenic had first been mentioned. But, whatever would Mr Pershore say?

A rather awkward pause ensued, broken by a timid knocking on the door. ‘Who’s there?’ Mrs Markle called out sharply.

‘It’s me, Kate, Mrs Markle. Sergeant Draper’s here, and he’s asking to see you.’

Doctor Formby and Mrs Markle exchanged startled glances. Sergeant Draper was a genial officer from the local police station. This was talking of the devil, with a vengeance. Had news of Jessie’s attack and its cause got abroad already?’

‘We’ll see him together,’ said the doctor, with sudden determination. ‘I don’t want this girl left alone. It had better be in here.’

Mrs Markle nodded. ‘Bring the sergeant down here, will you, Kate?’ she called.

Again that awkward pause, till the door opened and Sergeant Draper appeared. He was a massive, imposing-looking person, and usually wore an expression of the utmost cheerfulness. But now his countenance was one of portentous solemnity.

His eyebrows went up in astonishment as he recognised Doctor Formby and the unconscious girl on the sofa. ‘I beg pardon for intruding, I’m sure,’ he exclaimed. ‘I didn’t know that there was anybody taken bad in the house. Why, ’tis Jessie Twyford, surely!’ He took a step forward towards the sofa, then hurriedly checked himself, but his eyes remained fixed upon Jessie’s ashen face.

‘You didn’t know?’ said Doctor Formby slowly. ‘Then what brings you here, sergeant?’

Sergeant Draper averted his gaze from the girl, and fixed it on Mrs Markle. ‘It’s sorrowful news I bring,’ he replied. ‘Do you know where Mr Pershore went today, Mrs Markle?’

‘No, I don’t,’ said the housekeeper. ‘Mr Pershore doesn’t consult me on his comings and goings. To his office, likely enough. He usually goes there on Monday mornings.’

‘You didn’t know that he’d gone to the Motor Show, then?’

‘No, I didn’t. But why shouldn’t he, if he wanted to? It’s more than once that he’s spoken of buying a car.’

‘Well, however it may be, he did go to Olympia. They’ve just rung up the station from there.’

‘Rung up? What should they ring up for?’ And then a sudden comprehension of the sergeant’s meaning dawned upon Mrs Markle. ‘There’s—there’s nothing happened to Mr Pershore, is there?’ she whispered urgently.

The sergeant lowered his head. ‘He’s dead, ma’am,’ he replied gently. ‘Fainted away suddenly, and passed off without a bit of pain.’

Mrs Markle’s face contracted, but apart from that she gave no sign. Her experiences before she became Mr Pershore’s housekeeper had taught her to bear the hardest blows of Fate without complaint. The two men, watching her, had no indication of what was passing through her mind. Memories of childhood, perhaps. Nahum’s arm about her waist in that almost forgotten builder’s yard. Or of the future, stretching interminably into lonely old age, pervaded with the smell of soap-suds and dishwater.

Doctor Formby was the first to make any move. He took Mrs Markle’s arm and led her to a chair. Then he opened his bag, uncorked a bottle, and poured some of its contents into a glass. ‘Drink this!’ he said.

Mrs Markle obeyed him without protest. He watched her for a moment, then turned to the sergeant. ‘Do you know the cause of Mr Pershore’s death?’ he asked quietly.

‘No, sir, that I don’t. All they said on the telephone was that a gentleman had had a fit at the show and died. They’d found a card in his pocket with Mr Pershore’s name and address on it. When they described what the gentleman looked like I knew it must be Mr Pershore, and I told them so. Then they said I’d better come round here and break the news to his family. I thought the best thing I could do was to see Mrs Markle.’

Dr Formby seemed to give only half his attention to what the sergeant was saying. ‘What have they done with the body?’ he asked abruptly.

‘It’s been taken to the mortuary, sir. There’ll be an inquest, and after that the relatives …’

‘Oh, yes,’ exclaimed Doctor Formby impatiently. ‘I’ve never attended Mr Pershore, nor so far as I know has any other doctor in this town. But he’s always struck me as a man of at least average health. Yet you say he has died suddenly from some unascertained cause. Two or three hours ago that girl on the sofa, who’s at least as healthy as Mr Pershore, was taken suddenly ill. Queer, isn’t it?’

‘What you would call a remarkable coincidence, sir,’ replied the sergeant. ‘Is it anything serious that’s the matter with Jessie Twyford?’

‘That I’ll tell you later,’ said Doctor Formby. He went up to the housekeeper, who was sitting motionless in her chair. ‘You’ll be all right if we leave you, Mrs Markle? I’ll have a nurse round here in less than an hour.’

His voice seemed to galvanise her into life. ‘I shall be all right, doctor,’ she replied. ‘You can trust me to see that Jessie is properly looked after.’

The doctor and the policeman left the house. Mrs Markle, after seeing that her patient was properly wrapped up, went into the kitchen and asked Mrs Rugg to make her a cup of tea. Then she returned to the servants’ hall, and drew up a chair to the sofa.

But her thoughts were not of Jessie, who now appeared to be sleeping peacefully. Her brain was wrestling with the sergeant’s words, which refused to crystallise themselves into any credible fact. The idea of death and the idea of Mr Pershore were like drops of oil and vinegar, refusing to mingle. In her efforts to make herself realise that her employer was dead, everything else became of secondary importance. Even Jessie’s illness, Doctor Formby’s extraordinary suggestion that she had swallowed arsenic, seemed the merest trifles.

As she sipped the hot, strong tea, the central fact, though remaining incomprehensible, became fixed in her brain. Mr Pershore was dead. It was her obvious duty to inform his relatives without delay.

Nahum Pershore had been the youngest of three. Nancy Markle hardly remembered his two sisters. They had been much older than Nahum, had been out in the world when he was still a child playing in his father’s yard. But she knew all about them. Rebecca, the eldest, had married young Bryant, who worked in the office of the local solicitor. A pushing young fellow, was Bryant. He had passed all his examinations, and become a solicitor himself. Then he had gone into partnership in London. The Bryants had an only child, Philip, who had adopted his father’s profession, and was now a partner in the firm of Capes, Bryant and Capes, of Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Rebecca Bryant and her husband had both died many years ago. But Philip was very much alive. It was only the day before that he had spent the afternoon and evening at Firlands.