Полная версия

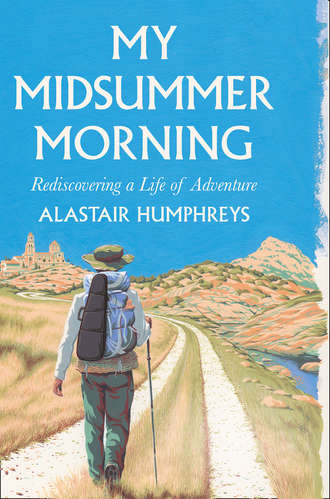

My Midsummer Morning

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook edition published by William Collins in 2019

Copyright © Alastair Humphreys, 2019

Extracts from As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning by Laurie Lee reproduced with permission of Curtis Brown Group Ltd, London, on behalf of the Beneficiaries of the Estate of Laurie Lee.

Copyright © Laurie Lee 1969

Here Comes the Sun, words and music by George Harrison © 1969 Harrisongs Limited. All Rights Reserved. International Copyright Secured.

Used by permission of Hal Leonard Europe Limited

Cover and interior illustrations by Neil Gower

All photographs © Alastair Humphreys

Alastair Humphreys asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this eBook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

Source ISBN: 9780008331825

Ebook Edition © May 2019 ISBN: 9780008331832

Version: 2019-05-20

Dedication

For Sarah

‘Little darling, the smiles returning to the faces.’

Epigraph

‘You asked for it. It’s up to you now.’

‘But I was in Spain, and to the new life beginning.’

Laurie Lee, As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Imagine

Life

One Moment

Laurie

Direction

Adventure

Becks

Music Lesson

Progress

Into Spain

First Play

Hope

Encouragement

Preparation

First Walk

First Night

Marriage

Dawn

The Pram in the Hall

Swifts

Kleos

Reverence

Polar

Grace

Help

Choices

Fear

Casting

One Day

Lost

Rhythm

Baggage

First Light

Buscando

Manna

Health Check

Bravery

Privilege

Camping

Changes

Hitchhiking

Loneliness

The People of this Earth

Siesta

Daily Bread

The Music in Me

Jungle

Postman

The Greatest Day

Evening

Last Light

Treasure

Coffee

Kindness

Gambling

The Art of Busking

Alone

Fiesta

Respite

Chorizo

Cassiopeia

Party

Forest

Permission

Last Days

Mountains

Way Back

River

Thunder Road

Last Play

The Wall

Last Night

Into Madrid

Home from Abroad

Reward

It’s All Right

Photos from the Adventure

Acknowledgements

The Violin Case

About the Author

About the Book

Books by Alastair Humphreys

Books by Laurie Lee

About the Publisher

AND HERE I WAS at last. I had imagined this moment for years. My dream was finally happening. I had worked hard to make it this far, spurred on by the anticipation of how happy I would be. Yet now that it was beginning, I felt only afraid and lonely. I breathed deeply to calm myself. The air here smelled different from home – warm and dry. I looked beyond the pine trees and the red tiled roofs, over the blue bay, and on to the distant, forested hills. I wanted to flee and hide up in those hills. They looked so quiet and so safe. But I could not leave. At least, not yet. Before I escaped this town there was one task I must do, the burden that was scaring me. I needed to play my violin.

I was hungry. My pockets were empty. I had to busk to earn some money. But I had never busked in my life, never even played in public before. I was terrible at the violin. What on earth was I doing?

I could not bring myself to unpack my new instrument. Instead, I kept walking. I scrunched my eyes against the glare of the sun, crossing streets to cling to the shaded sides. My rucksack was cumbersome, heavier than I had imagined. I eyed a wishing well in a park. The water glittered with coins. I was both disappointed and relieved that the coins tossed in exchange for dreams were beyond my reach. It was a little soon to resort to stealing children’s money and wishes. I prowled the streets, nervous, eyes to the ground, scanning for loose change. I was looking for money, but mostly I was searching for excuses. The well is always deep with those.

Eventually I made my way back to the town centre, to what I had already concluded – two or three times – was the best plaza for busking. There were no cars, but plenty of pedestrians. A church shaded one side from the sun. Let’s get this over and done with, I told myself.

But my heart sank when I noticed that another busker had beaten me to it. A young man sat cross-legged in ‘my’ plaza, hunched over a recorder. This was not the time for an interloper! Usually, I would barely have noticed him: he was not a good musician and was playing very quietly. He wore a denim jacket and dark greasy hair fell over his face. He wasn’t charismatic and did not appear to be very successful (nor even conspicuously, successfully destitute). But today, as I dawdled in the shadows across the plaza, I saw him in a different light. He was a musician! He knew how to play songs! Not only that, but he had been brave enough to snaffle the premium spot in town. His hat on the pavement already had money in it. I wished I could be like him. I wanted to ask how much he earned, to be in his presence, to seek his wisdom and his blessing. But I was too shy.

I slunk off and found a different plaza, sleepy and set back from the road. I dumped my rucksack by the fountain. The sun was high now, so I stooped to drink and splash my face. My back was sweaty. A waiter unrolled the sun shade outside his restaurant. ‘Casa Gazpara,’ I read. ‘Vinos, Comidas, Mariscos, Tapas.’ I remembered how hungry I was. I had only butterflies in my stomach. Some drunks swayed and slurred on the other side of the fountain. I couldn’t even afford a dash of their Dutch courage.

I had not felt this apprehensive since the day a few years ago when I’d climbed aboard a small green rowing boat, picked up the oars and set off to try to row across the Atlantic Ocean. The prospect of playing a few tunes in a quiet plaza agitated me as much as colossal waves a thousand miles from land. But in place of storms and capsize, here I dreaded failure and shame. I was frightened of appearing a fool and worried what people would think about me. I knew this was pathetic behaviour for a man in his thirties, but the vulnerability was fascinating. What if I fall, asks the poem? Oh, but what if you fly?

I glanced around, then unzipped the violin case, furtively, as if it contained a gun. I was committed now, too far across the floor at the school disco to swerve my decision to ask the girl to dance. An apt comparison for I never dared do that either. I positioned the shoulder rest and tightened the bow. I had known that performing in public would be much harder than practising alone, which was why I had waited until today to try it. I had deliberately avoided getting accustomed to busking when the consequences did not matter. I chose to wait until it counted – until I was alone and penniless in a foreign country – because I wanted to experience the full shock of plunging in. I wanted to make this as hard as possible. I wanted that until I got it.

Pensioners watched the world go by from a bench near the fountain. They passed occasional comments to each other and pointed things out that caught their attention. One gentleman wore a Panama hat and yellow trainers; another was in a tweed jacket and dark glasses. Now they all turned in my direction, curious. I looked away, avoiding their gaze as I extended the legs of my new music stand. I tried to recall how buskers usually set everything up. I had never paid attention before. A gang of schoolchildren crossed the plaza, laughing and chatting. I pegged my music sheets onto the stand. A hush seemed to descend on the town and I stood lonely among the crowd. At this point a movie would cut to slow motion. I tuned the violin as best I could, fingers fumbling at the pegs. Don’t die wondering, they say. Better to die on your feet than live on your knees, they say.

Die? Don’t be ridiculous! It’s only a bloody violin. Lo siento, España. I am so sorry, Spain. I lifted my face to the sun, smiled, took a deep breath, and began to play.

Imagine

SOMETIMES, WHEN I READ travel books, I say to myself, ‘You could put this book down right now, step outside, and just go. The sunlit road calling you. Nowhere to be but there. The freedom all yours to choose.’

Imagine.

If I could go, would I?

A dusty white road winding through orange groves. Summer heat and the tang of citrus. Cicadas shrill the still silence. A silver ribbon of river threads the green valley below. A cluster of stone cottages and the dull clang of a church bell. The blue smudge of distant mountains. The day long and open and waiting for me.

As I hike, I cradle an imaginary violin, snug under my chin, fingers dancing on the strings. My right hand plays the pretend bow and I whistle the tune as I walk. One of the songs of my life, soaked deep into my marrow, personal and precious. I break from a whistled verse to yell the chorus. Stamping the beat with my battered boots interrupts the rhythm of walking, but helps the exuberance bust out of my body. A song, a dance, a journey, all of my own.

The sun pounds and burns my back. But I relish it as a burnished medal for 20 miles earned each day beneath it. I have become lean but strong, stripped back. My pack contains the bare minimum, and that is enough. A blanket, bread, half a bottle of water. Strapped to the outside is my fiddle, the real one. It is fragile, smooth maple, and the magic key to this journey. Without it, I am ordinary – just another man tramping through Spain across the ages. But with this violin, I become a music maker and a dreamer of dreams. Tonight, beneath the stars in that village across the valley, I will bring music and laughter. My hat upturned upon the ground, dancers tossing coins as I play. They shine bright as they spin in the moonlight.

Wherever I walk, I sow happiness in my wake, and the world lies all before me. The weary satisfaction of physical effort beneath a summer sky. The focused simplicity of creating a living from the art you love. Carefree independence and the enticing spontaneity of the open road.

Just imagine.

If you could go, would you?

Life

I LOOKED UP. LET out a sigh. I was not in Spain, but somewhere near Slough, on a slow train bound for nowhere. I closed my book, a tale of sunshine, music and adventure. Monday morning trundled past, laden with drizzle and gloom. Flat-roofed pubs, warehouses, muddy park pitches. This was where I lived. This was my life.

Books carry me far away. I enjoy that, for I am cursed with fernweh, a yearning for distant places. Throughout my adult life I have either been wandering the world, preparing to, or wishing that I was. I grow excited every time I pack a bag and slip my passport into my pocket, but despondent when I arrive back home and put the passport away in a drawer. Returning inevitably disappoints, pricking my hope that going away might somehow have fixed my problems.

I first read As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning when I was a student, dreaming of travel and getting ready to live. Laurie Lee had never left England before he docked in Spain in 1935. He hadn’t given much thought to ‘what would happen then, for already I saw myself there, brown as an apostle, walking the white dust roads through the orange groves’.

Laurie’s hazy plan was to walk south from Vigo, exploring a new country and playing the violin to pay his way. He had no schedule or deadline. He slept under the stars, lived on bread and cheap wine, and flirted happily. Laurie’s book is a paean to pure adventure, free from responsibility, made possible by the music from his violin. Reading it whisked me away to sunlit hills and villages, and I dreamed of one day following Laurie to Galicia. I wanted the same uncertainty, freedom and excitement in my own predictable, routine-dominated life.

But there was one fundamental problem. I could not play the violin, nor any other musical instrument. I had learned the piano for about a year when I was 10, until my mum yielded to the tedium of getting a reluctant, talentless boy to practise and allowed me to quit. I remember the music teacher at school – a bully later outed as a paedophile – mocking my timid and tuneless singing in front of a laughing class. I burned with shame and fought back tears. Forever after, I dreaded music lessons. Today, merely the thought of having to sing in public makes me prickle with nerves. I hate karaoke or dancing. My heart sinks whenever I hear the line, ‘introduce yourself to the group and tell us a bit about yourself’.

Realistically, then, I could never busk through Spain. I had neither the skill nor the personality. Yet following Laurie’s route with a wallet rather than a violin would be merely a walking holiday. That was missing the point. So, for 15 years, I shelved the idea. Instead, I looked elsewhere for adventure. I cycled round the world. I walked across southern India and the Empty Quarter desert. I crossed Iceland by packraft. I rowed the Atlantic, spent time in Greenland and on the frozen Arctic Ocean near the North Pole. I was ridiculously fit. I hung out with intelligent, daredevil, ambitious misfits. Each expedition gave me ideas and skills for new journeys. They were miraculous days of joy and wonder. I even managed to turn these escapades into my career. I gave talks and wrote articles and books. I was the luckiest man in town.

But then, in life’s musical chairs, the music stopped. And I realised I had been sitting in this threadbare seat for years now, staring out of commuter train windows. I called myself an Adventurer, but I was not living adventurously anymore. I was no longer proud of the story I was writing. The woman next to me, late for work and furious, tapped her displeasure in a series of to-and-fro text messages at my shoulder, clammy in her perfumed blouse. Tap-tap-tap. Pause. Beep-beep. Tap-tap-tap.

I shifted my focus to my reflection in the dirty, rain-spattered window. I didn’t like what I saw. I was bored with myself. I had grown up and settled down. For most people this is the conventional, accepted route in life. I envy them. But it was not working for me.

I wanted uncertainty and doubt in my life, and the courage, energy and spirit to face them. I needed to move in order to breathe. I craved being on the road again, inhaling the heady air of places new with just one difficult but simple goal to chase. Instead, I was trundling round and round telling old tales to pay the bills. I had given up.

One Moment

I GLANCED DOWN AT the book in my lap, closed my eyes, and sighed. Then, without thinking, I pulled my phone from the pocket of my jeans, contorting myself on the cramped seat to do so. But instead of the artificial escape of social media, today I opened Google.

‘Find a local violin teacher’, I thumbed.

A website popped up, I found an email address, and before I had time to dwell on it, I began to type.

Fri, 20 Nov 2015, 11:56

TO: Becks Violin

FROM: Alastair Humphreys

SUBJECT: Can you teach me the violin really quickly?

Every journey, every change in direction, begins with one tiny deed, quick to revoke and easy to forget. An action so devoid of binding consequence that there is no reason not to take it. No reason except inertia and fear. The hardest part of every adventure is this one moment, small yet significant. It is the decision to begin, to get moving, to push back the boundaries of your normality, perhaps even to turn your whole life around.

I hit ‘Send’ and went back to my book.

Laurie

LAURIE LEE AND I first met as teenagers, though he was 63 years older than me. Laurie lived in a lush valley in Gloucestershire where, emboldened by booze, he was busy getting his leg over with half the girls in the village. I was studying Cider with Rosie for English GCSE, avoiding eye contact with the teacher – all irascible nicotine and tweed – and willing the lunch bell to save me. Not for the final time, I envied Laurie.

Cider with Rosie is the story of Laurie’s childhood. It is vivid with eccentric village characters and tales of his friends roaming the countryside. Laurie grew up in a chaotic but loving home with his mother and six siblings. One of his earliest memories was of a man in uniform knocking on the door to ask for a cup of tea. Laurie’s mother had ‘brought him in and given him a whole breakfast’. The soldier was a deserter from World War I, sleeping rough in the woods.

Laurie left school at 14 and went on to become a poet, screenwriter and author. He procrastinated prolifically in the pubs and clubs and literary parties of London. When he did write, he worked slowly with a soft pencil, editing and re-editing obsessively. Throughout his life, Laurie was plagued by self-doubt and often considered himself a failure, despite the unexpected, extraordinary success of Cider with Rosie, which sold more than six million copies. He described himself as ‘a melancholic man who likes to be thought merry’.

The next time Laurie and I met, in our twenties, we were both looking for adventure. I was in my final year at university when I picked up an old copy of As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning, the sequel to Cider with Rosie, in a charity shop at the end of my street.

‘You’ll enjoy that,’ remarked Ziggy, the friend I was browsing with. ‘It’s about a guy wandering around Spain, half drunk with wine, and a bunch of dark-eyed beauties.’

Ziggy and I convened regularly in the greasy spoon café next door to nurse hangovers or refuel after frosty runs along the river. We spoke incessantly of travel and adventure ideas. Ziggy wanted to live in Africa. I wanted to hit the road. We were impatient for our course to end and the chance to charge across the start line into real life. Until then, I was burning off my energy with the university boxing club, muddy football matches and tomfoolery. It was fun, but what I really wanted was, once again, what Laurie Lee was doing.

Ziggy and I headed to the café with our small pile of books. I ordered mugs of tea while Ziggy found a table in the corner. He cleared a circle in the steamed-up window with his sleeve, then peered out. I took a slurp of tea and opened my new book. I have the same copy beside me today, faded and torn. It falls open to well-thumbed passages for I reread it almost every year.

Back then, I gorged on books about polar exploration and mountaineering. These tales on the margins of possibility – the best of the best doing the hardest of the hard – were exhilarating but unattainable to someone as callow as me. Laurie’s story was immediately different. It read like a poetic version of my own life. The cover showed a young man walking towards a red-roofed village under a clear blue sky. Bored with his claustrophobic life, Laurie dreamed of seeing the world. He didn’t have much cash. His mum waved goodbye from the garden gate. He felt more homesick than heroic. So far, so me.

I was disillusioned preparing for a career that did not excite me as much as I thought life ought to. I had gone to university only because all my friends were going. It was a privileged but naive decision, for it had literally not occurred to me that it was possible to do anything else. I was training to be a teacher, but dreaming of being an explorer. While my classmates sent their CVs out to schools, I researched joining the Foreign Legion, the SAS, or MI6. I wanted mayhem, not timetables. Today, it astonishes me how little I knew of life back then that I saw only binary options: the Legion, or lesson planning. Sensible and realistic, or thrilling but absurd.

‘How does anything exciting happen in a blasted office?’ Laurie exclaimed after taking a job with Messrs Randall & Payne, Chartered Accountants, when he left school. Laurie’s girlfriend urged, ‘If it isn’t impertinent to ask, why don’t you clear out of Stroud? You’re simply wasting your time, and you’ll never be content there. Even if you don’t find happiness you’ll at least be living.’

Soon after, Laurie wrote a brief resignation letter.

‘Dear Mr Payne, I am not suited to office work and resign from my job with your firm. Yours sincerely Laurie Lee.’