Полная версия

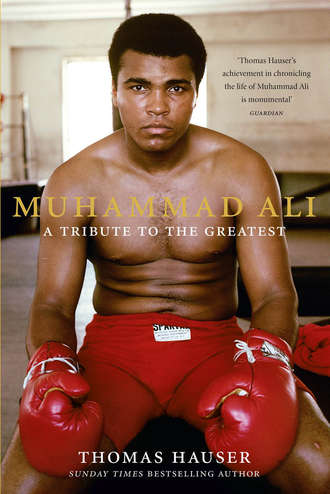

Muhammad Ali: A Tribute to the Greatest

Kwame Turé [formerly known as Stokely Carmichael]: Muhammad Ali used himself as a perfect instrument to advance the struggle of humanity by demonstrating clearly that principles are more important than material wealth. It’s not just what Ali did. The way he did it was just as important.

Wilbert McClure [Ali’s room-mate and fellow gold medal winner at the Olympics]: He always carried himself with his head high and with grace and composure. And we can’t say that about all of his detractors; some of them in political office, some of them in pulpits, some of them thought of as nice, upstanding citizens. No, we can’t say that about all of them.

Charles Morgan [former Director of the ACLU Southern Office]: I remember thinking at the time, what kind of a foolish world am I living in where people want to put this man in jail.

Dave Kindred: He was one thing, always. He was always brave.

Ali was far from perfect, and it would do him a disservice not to acknowledge his flaws. It’s hard to imagine a person so powerful yet at times so naïve; almost on the order of Forrest Gump. On occasion, Ali has acted irrationally. He cherishes honour and is an honourable person, but too often excuses dishonourable behaviour in others. His accommodation with dictators like Mobuto Sese Seko and Ferdinand Marcos and his willingness to fight in their countries stand in stark contrast to his love of freedom. There is nothing redeeming in one black person calling another black person a ‘gorilla’, which was the label that Ali affixed to Joe Frazier. Nor should one gloss over Ali’s past belief in racial separatism and the profligate womanising of his younger days. But the things that Ali has done right in his life far outweigh the mistakes of his past. And the rough edges of his earlier years have been long since forgiven or forgotten.

What remains is a legacy of monumental proportions and a living reminder of what people can be. Muhammad Ali’s influence on an entire nation, black and white, and a whole world of nations has been incalculable. He’s not just a champion. A champion is someone who wins an athletic competition. Ali goes beyond that.

It was inevitable that someone would come along and do what Jackie Robinson did. Robinson did it in a glorious way that personified his own dignity and courage. But if Jackie Robinson hadn’t been there, someone else – Roy Campanella, Willie Mays, Henry Aaron – would have stepped in with his own brand of excitement and grace and opened baseball’s doors. With or without Jack Johnson, eventually a black man would have won the heavyweight championship of the world. And sooner or later, there would have been a black athlete who, like Joe Louis, was universally admired and loved.

But Ali carved out a place in history that was, and remains, uniquely his own. And it’s unlikely that anyone other than Muhammad Ali could have created and fulfilled that role. Ali didn’t just mirror his times. He wasn’t a passive figure carried along by currents stronger than he was. He fought the current; he swam against the tide. He stood for something, stayed with it, and prevailed.

Muhammad Ali is an international treasure. More than anyone else of his generation, he belongs to the people of the world and is loved by them. No matter what happens in the years ahead, he has already made us better. He encouraged millions of people to believe in themselves, raise their aspirations and accomplish things that might not have been done without him. He wasn’t just a standard-bearer for black Americans. He stood up for everyone.

And that’s the importance of Muhammad Ali.

MUHAMMAD ALI AND BOXING

(1996)

‘You could spend twenty years studying Ali,’ Dave Kindred once wrote, ‘and still not know what he is or who he is. He’s a wise man, and he’s a child. I’ve never seen anyone who was so giving and, at the same time, so self-centred. He’s either the most complex guy that I’ve ever been around or the most simple. And I still can’t figure out which it is. I mean, I truly don’t know. We were sure who Ali was only when he danced before us in the dazzle of the ring lights. Then he could hide nothing.’

And so it was that the world first came to know Muhammad Ali, not as a person, not as a social, political or religious figure, but as a fighter. His early professional bouts infuriated and entertained as much as they impressed. Cassius Clay held his hands too low. He backed away from punches, rather than bobbing and weaving out of danger, and lacked true knockout power. Purists cringed when he predicted the round in which he intended to knock out his opponent, and grimaced when he did so and bragged about each new conquest.

Then, at the age of 22, Clay challenged Sonny Liston for the world heavyweight crown. Liston was widely regarded as the most intimidating, ferocious, powerful fighter of his era. Clay was such a prohibitive underdog that Robert Lipsyte, who covered the bout for The New York Times, was instructed to ‘find out the directions from the arena to the nearest hospital, so I wouldn’t waste deadline time getting there after Clay was knocked out’. But as David Ben-Gurion once proclaimed, ‘Anyone who doesn’t believe in miracles is not a realist.’ Cassius Clay knocked out Sonny Liston to become heavyweight champion of the world.

Officially, Ali’s reign as champion was divided into three segments. And while he fought through the administrations of seven Presidents, his greatness as a fighter was most clearly on display in the three years after he first won the crown. During the course of 37 months, Ali fought ten times. No heavyweight in history has defended his title more frequently against more formidable opposition in more dominant fashion than Ali did in those years.

Boxing, in the first instance, is about not getting hit. ‘And I can’t be hit,’ Ali told the world. ‘It’s impossible for me to lose because there’s not a man on earth with the speed and ability to beat me.’

In his rematch with Liston, which ended in a first-round knockout, Ali was hit only twice. Victories over Floyd Patterson, George Chuvalo, Henry Cooper, Brian London and Karl Mildenberger followed. Then, on 14 November 1966, Ali did battle against Cleveland Williams. Over the course of three rounds, Ali landed more than one hundred punches, scored four knockdowns and was hit a total of three times. ‘The hypocrites and phonies are all shook up because everything I said would come true did come true,’ Ali chortled afterward. ‘I said I was The Greatest, and they thought I was just acting the fool. Now, instead of admitting that I’m the best heavyweight in all history, they don’t know what to do.’

Ali’s triumph over Cleveland Williams was followed by victor-ies over Ernie Terrell and Zora Folley. Then, after refusing induction into the United States Army, he was stripped of his title and forced out of boxing. ‘If I never fight again, this is the last of the champions,’ Ali said of his, and boxing’s, plight. ‘The next title is a political belt, a racial belt, an organisation belt. There’s no more real world champion until I’m physically beat.’

In October 1970, Ali was allowed to return to boxing, but his skills were no longer the same. The legs that had allowed him to ‘dance’ for 15 rounds without stopping no longer carried him as surely around the ring. His reflexes, while still superb, were no longer lightning fast. Ali prevailed in his first two comeback fights, against Jerry Quarry and Oscar Bonavena. Then he challenged Joe Frazier, who was the ‘organisation’ champion by virtue of victories over Buster Mathis and Jimmy Ellis.

‘Champion of the world? Ain’t but one champion,’ Ali said before his first bout against Frazier. ‘How you gonna have two champions of the world? He’s an alternate champion. The real champion is back now.’ But Frazier thought otherwise. And on 8 March 1971, he bested Ali over 15 brutal rounds.

‘He’s not a great boxer,’ Ali said afterward. ‘But he’s a great slugger, a great street fighter, a bull fighter. He takes a lot of punches, his eyes close and he just keeps coming. I figured he could take the punches. But one thing surprised me in this fight, and that’s that he landed his left hook as regular as he did. Usually, I don’t get hit over and over with the same punch, and he hit me solid a lot of times.’

Some fighters can’t handle defeat. They fly so high when they’re on top that a loss brings them irrevocably crashing down. ‘What was interesting to me after the loss to Frazier,’ says Ferdie Pacheco, ‘was we’d seen this undefeatable guy. Now how was he going to handle defeat? Was he going to be a cry-baby? Was he going to be crushed? Well, what we found out was, this guy takes defeat like he takes victory. All he said was, “I’ll beat him next time.”’

What Ali said was plain and simple: ‘I got to whup Joe Frazier because he beat me. Anybody would like to say, “I retired undefeated.” I can’t say that no more. But if I could say, “I got beat, but I came back and beat him,” I’d feel better.’

Following his loss to Frazier, Ali won ten fights in a row; eight of them against world-class opponents. Then, in March 1973, he stumbled when a little-known fighter named Ken Norton broke his jaw in the second round en route to a 12-round upset decision.

‘I knew something was strange,’ Ali said after the bout, ‘because, if a bone is broken, the whole internalness in your body, everything, is nauseating. I didn’t know what it was, but I could feel my teeth moving around, and I had to hold my teeth extra tight to keep the bottom from moving. My trainers wanted me to stop. But I was thinking about those nineteen thousand people in the arena and Wide World of Sports, millions of people at home watching in 62 countries. So what I had to do was put up a good fight; go the distance and not get hit on the jaw again.’

Now Ali had a new target; a priority ahead of even Joe Frazier. ‘After Ali got his jaw broke, he wanted Norton bad,’ recalls Lloyd Wells, a long-time Ali confidant. ‘Herbert Muhammad [Ali’s manager] was trying to put him in another fight, and Ali kept saying, “No, get me Norton. I want Norton.” Herbert was saying, but we got a big purse; we got this, and we got that. And Ali was saying, “No, just get me Norton. I don’t want nobody but Norton.”’

Ali got Norton – and beat him. Then, after an interim bout against Rudi Lubbers, he got Joe Frazier again – and beat him too. From a technical point of view, the second Ali–Frazier bout was probably Ali’s best performance after his exile from boxing. He did what he wanted to do, showing flashes of what he’d once been as a fighter but never would be again. Then Ali journeyed to Zaïre to challenge George Foreman, who had dethroned Frazier to become heavyweight champion of the world.

‘Foreman can punch but he can’t fight,’ Ali said of his next foe. But most observers thought that Foreman could do both. As was the case when Ali fought Sonny Liston, he entered the ring a heavy underdog. Still, studying his opponent’s armour, Ali thought he detected a flaw. Foreman’s punching power was awesome, but his stamina and will were suspect. Thus, the ‘rope-a-dope’ was born.

‘The strategy on Ali’s part was to cover up, because George was like a tornado,’ former boxing great Archie Moore, who was one of Foreman’s cornermen that night, recalls. ‘And when you see a tornado coming, you run into the house and you cover up. You go into the basement and get out of the way of that strong wind, because you know that otherwise it’s going to blow you away. That’s what Ali did. He covered up and the storm was raging. But after a while, the storm blew itself out.’

Or phrased differently, ‘Yeah, Ali let Foreman punch himself out,’ says Jerry Izenberg. ‘But the rope-a-dope wouldn’t have worked against Foreman for anyone in the world except Ali, because on top of everything else, Ali was tougher than everyone else. No one in the world except Ali could have taken George Foreman’s punches.’

Ali stopped Foreman in the eighth round to regain the heavyweight championship. Then, over the next thirty months at the peak of his popularity as champion, he fought nine times. Those bouts showed Ali to be a courageous fighter, but a fighter on the decline.

Like most ageing combatants, Ali did his best to put a positive spin on things. But viewed in realistic terms, ‘I’m more experienced’ translated into ‘I’m getting older.’ ‘I’m stronger at this weight’ meant ‘I should lose a few pounds.’ ‘I’m more patient now’ was a cover for ‘I’m slower.’

Eight of Ali’s first nine fights during his second reign as champion did little to enhance his legacy. But sandwiched in between matches against the likes of Jean-Pierre Coopman and Richard Dunn and mediocre showings against more legitimate adversaries, Ali won what might have been the greatest fight of all time.

On 1 October 1975, Ali and Joe Frazier met in the Philippines, six miles outside of Manila, to do battle for the third time.

‘You have to understand the premise behind that fight,’ Ferdie Pacheco recalls. ‘The first fight was life and death, and Frazier won. Second fight: Ali figures him out; no problem, relatively easy victory for Ali. Then Ali beats Foreman, and Frazier’s sun sets. And I don’t care what anyone says now; all of us thought that Joe Frazier was shot. We all thought that this was going to be an easy fight. Ali comes out, dances around, and knocks him out in eight or nine rounds. That’s what we figured. And you know what happened in that fight. Ali took a beating like you’d never believe anyone could take. When he said afterward that it was the closest thing he’d ever known to death – let me tell you something: if dying is that hard, I’d hate to see it coming. But Frazier took the same beating. And in the fourteenth round, Ali just about took his head off. I was cringing. The heat was awesome. Both men were dehydrated. The place was like a time-bomb. I thought we were close to a fatality. It was a terrible moment, and then Joe Frazier’s corner stopped it.’

‘Ali–Frazier III was Ali–Frazier III,’ says Jerry Izenberg. ‘There’s nothing to compare it with. I’ve never witnessed anything like it. And I’ll tell you something else. Both fighters won that night, and both fighters lost.’

Boxing is a tough business. The nature of the game is that fighters get hit. Ali himself inflicted a lot of damage on ring opponents during the course of his career. And in return: ‘I’ve been hit a lot,’ he acknowledged, one month before the third Frazier fight. ‘I take punishment every day in training. I take punishment in my fights. I take a lot of punishment; I just don’t show it.’

Still, as Ferdie Pacheco notes, ‘The human brain wasn’t meant to get hit by a heavyweight punch. And the older you get, the more susceptible you are to damage. When are you best? Between fifteen and thirty. At that age, you’re growing, you’re strong, you’re developing. You can take punches and come back. But inevitably, if you keep fighting, you reach an age when every punch can cause damage. Nature begins giving you little bills and the amount keeps escalating, like when you owe money to the IRS and the government keeps adding and compounding the damage.’

In Manila, Joe Frazier landed 440 punches, many of them to Ali’s head. After Manila would have been a good time for Ali to stop boxing, but too many people had a vested interest in his continuing to fight. Harold Conrad served for years as a publicist for Ali’s bouts. ‘You get a valuable piece of property like Ali,’ Conrad said shortly before his death. ‘How are you going to put it out of business? It’s like shutting down a factory or closing down a big successful corporation. The people who are making money off the workers just don’t want to do it.’

Thus, Ali fought on.

In 1977, he was hurt badly but came back to win a close decision over Earnie Shavers. ‘In the second round, I had him in trouble,’ Shavers remembers. ‘I threw a right hand over Ali’s jab, and I hurt him. He kind of wobbled. But Ali was so cunning, I didn’t know if he was hurt or playing fox. I found out later that he was hurt. But he waved me in, so I took my time to be careful. I didn’t want to go for the kill and get killed. And Ali was the kind of guy who, when you thought you had him hurt, he always seemed to come back. The guy seemed to pull off a miracle each time. I hit him a couple of good shots, but he recovered better than any other fighter I’ve known.’

Next up for Ali was Leon Spinks, a novice with an Olympic gold medal but only seven professional fights.

‘Spinks was in awe of Ali,’ Ron Borges of the Boston Globe recalls. ‘The day before their first fight, I was having lunch in the coffee shop at Caesars Palace with Leon and [his trainer] Sam Solomon. No one knew who Leon was. Then Ali walked in, and everyone went crazy. “Look, there’s Ali! Omigod, it’s him!” And Leon was like everybody else. He got all excited. He was shouting, “Look, there he is! There’s Ali!” In 24 hours, they’d be fighting each other, but right then, Leon was ready to carry Ali around the room on his shoulders.’

The next night, Spinks captured Ali’s title with a relentless 15-round assault. Seven months later, Ali returned the favour, regaining the championship with a 15-round victory of his own. Then he retired from boxing, but two years later made an ill-advised comeback against Larry Holmes.

‘Before the Holmes fight, you could clearly see the beginnings of Ali’s physical deterioration,’ remembers Barry Frank, who was representing Ali in various commercial endeavours on behalf of IMG. ‘The huskiness had already come into his voice and he had a little bit of a balance problem. Sometimes he’d get up off a chair and, not stagger, but maybe take a half step to get his balance.’

Realistically speaking, it was obvious that Ali had no chance of beating Holmes. But there was always that kernel of doubt. Would beating Holmes be any more extraordinary than knocking out Sonny Liston and George Foreman? Ali himself fanned the flames. ‘I’m so happy going into this fight,’ he said shortly before the bout. ‘I’m dedicating this fight to all the people who’ve been told, you can’t do it. People who drop out of school because they’re told they’re dumb. People who go to crime because they don’t think they can find jobs. I’m dedicating this fight to all of you people who have a Larry Holmes in your life. I’m gonna whup my Holmes, and I want you to whup your Holmes.’

But Holmes put it more succinctly. ‘Ali is 38 years old. His mind is making a date that his body can’t keep.’

Holmes was right. It was a horrible night. Old and seriously debilitated from the effects of an improperly prescribed drug called Thyrolar, Ali was a shell of his former self. He had no reflexes, no legs, no punch. Nothing, except his pride and the crowd chanting, ‘Ali! Ali!’

‘I really thought something bad might happen that night,’ Jerry Izenberg recalls. ‘And I was praying that it wouldn’t be the something that we dread most in boxing. I’ve been at three fights where fighters died, and it sort of found a home in the back of my mind. I was saying, I don’t want this man to get hurt. Whoever won the fight was irrelevant to me.’

It wasn’t an athletic contest; just a brutal beating that went on and on. Later, some observers claimed that Holmes lay back because of his fondness for Ali. But Holmes was being cautious, not compassionate. ‘I love the man,’ he later acknowledged. ‘But when the bell rung, I didn’t even know his name.’

‘By the ninth round, Ali had stopped fighting altogether,’ Lloyd Wells remembers. ‘He was just defending himself, and not doing a good job of that. Then, in the ninth round, Holmes hit him with a punch to the body, and Ali screamed. I never will forget that as long as I live. Ali screamed.’

The fight was stopped after 11 rounds. An era in boxing – and an entire historical era – was over. Now, years later, in addition to his more important social significance, Ali is widely recognised as the greatest fighter of all time. He was graced with almost unearthly physical skills and did everything that his body allowed him to do. In a sport that is often brutal and violent, he cast a long and graceful shadow.

How good was Ali?

‘In the early days,’ Ferdie Pacheco recalls, ‘he fought as though he had a glass jaw and was afraid to get hit. He had the hyper reflexes of a frightened man. He was so fast that you had the feeling, “This guy is scared to death; he can’t be that fast normally.” Well, he wasn’t scared. He was fast beyond belief and smart. Then he went into exile; and when he came back, he couldn’t move like lightning any more. Everyone wondered, ‘What happens now when he gets hit?’ That’s when we learned something else about him. That sissy-looking, soft-looking, beautiful-looking child-man was one of the toughest guys who ever lived.’

Ali didn’t have one-punch knockout power. His most potent offensive weapon was speed; the speed of his jab and straight right hand. But when he sat down on his punches, as he did against Joe Frazier in Manila, he hit harder than most heavyweights. And in addition to his other assets, he had superb footwork, the ability to take a punch, and all of the intangibles that go into making a great fighter.

‘Ali fought all wrong,’ acknowledges Jerry Izenberg. ‘Boxing people would say to me, “Any guy who can do this will beat him. Any guy who can do that will beat him.” And after a while, I started saying back to them, “So you’re telling me that any guy who can outjab the fastest jabber in the world can beat him. Any guy who can slip that jab, which is like lightning, not get hit with a hook off the jab, get inside, and pound on his ribs can beat him. Any guy. Well, you’re asking for the greatest fighter who ever lived, so this kid must be pretty good.”’

And on top of everything else, the world never saw Muhammad Ali at his peak as a fighter. When Ali was forced into exile in 1967, he was getting better with virtually every fight. The Ali who fought Cleveland Williams, Ernie Terrell and Zora Folley was bigger, stronger, more confident and more skilled than the 22-year-old who, three years earlier, had defeated Sonny Liston. But when Ali returned, his ring skills were diminished. He was markedly slower and his legs weren’t the same.

‘I was better when I was young,’ Ali acknowledged later. ‘I was more experienced when I was older; I was stronger; I had more belief in myself. Except for Sonny Liston, the men I fought when I was young weren’t near the fighters that Joe Frazier and George Foreman were. But I had my speed when I was young. I was faster on my legs and my hands were faster.’

Thus, the world never saw what might have been. What it did see, though, in the second half of Ali’s career, was an incredibly courageous fighter. Not only did Ali fight his heart out in the ring; he fought the most dangerous foes imaginable. Many champions avoid facing tough challengers. When Joe Louis was champion, he refused to fight certain black contenders. After Joe Frazier defeated Ali, his next defences were against Terry Daniels and Ron Stander. Once George Foreman won the title, his next bout was against José Roman. But Ali had a different creed. ‘I fought the best, because if you want to be a true champion, you got to show people that you can whup everybody,’ he proclaimed.

‘I don’t think there’s a fighter in his right mind that wouldn’t admire Ali,’ says Earnie Shavers. ‘We all dreamed about being just half the fighter that Ali was.’

And of course, each time Ali entered the ring, the pressure on him was palpable. ‘It’s not like making a movie where, if you mess up, you stop and reshoot,’ he said shortly before Ali–Frazier III. ‘When that bell rings and you’re out there, the whole world is watching and it’s real.’

But Ali was more than a great fighter. He was the standard-bearer for boxing’s modern era. The 1960s promised athletes who were bigger and faster than their predecessors. Ali was the prototype for that mould. Also, he was part and parcel of the changing economics of boxing. Ali arrived just in time for the advent of satellites and closed circuit television. He carried heavyweight championship boxing beyond the confines of the United States and popularised the sport around the globe.