Полная версия

Measuring America

MEASURING AMERICA

How the United States was Shaped by the Greatest Land Sale in History

ANDRO LINKLATER

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

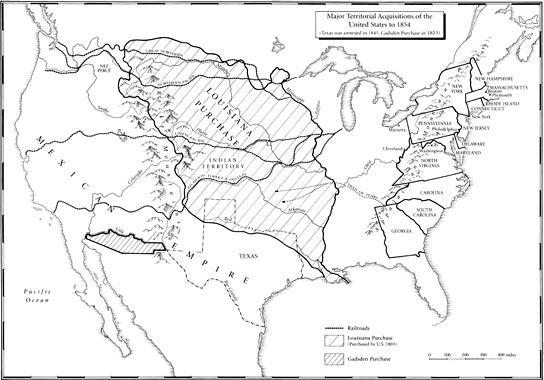

MAPS

INTRODUCTION

1 The Invention of Property

2 Precise Confusion

3 A Hunger for Land

4 Life, Liberty and What?

5 Simple Arithmetic

6 A Line in the Wilderness

7 The French Dimension

8 Democratic Decimals

9 Annie’s Ounce

10 The Birth of the Metric System

11 Dombey’s Luck

12 The End of Rufus

13 The Immaculate Grid

14 The Shape of Cities

15 Hassler’s Passion

16 The Dispossessed

17 The Limit of Enclosure

18 Four Against Ten

19 Metric Triumphant

EPILOGUE: The Witness Tree

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ALSO BY THE AUTHOR

COPYRIGHT

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

MAPS

INTRODUCTION

In every country with an industrial history there are towns like East Liverpool, Ohio. They were built close to the coalfields that provided their energy and on the banks of large rivers that carried away their heavy products. On the Clyde in Scotland, the Tees in England, the Ruhr in Germany, mighty structures of iron and steel were smelted, beaten and annealed to make the skeleton for the first modern society, and the towns grew rich and confident in a grey haze of fumes and steam and effluent. Today their colours are rusty metal and faded red brick, the air is clear, the atmosphere uncertain, and in the shabby streets regeneration is pitted against boredom and drugs.

Clay was the material that made East Liverpool wealthy, Pennsylvania coal fuelled the furnaces, and the Ohio river carried away enough plates and cups to let the inhabitants boast that the town was ‘the pottery capital of the world’. Where once dozens of factories and chemical works lined the banks, the only reminder now of East Liverpool’s industrial past is a solitary chimney stack pumping heavy coils of smoke into the sky. The barges still come up the Ohio river carrying minerals and fertilisers, but mostly for use across the river in the nearby Pittsburgh area. They unload at depots like that belonging to the S.H. Bell Company, whose functional warehouses and concrete docks annually handle thousands of tons of steel and copper at the upriver end of town.

The place could hardly be more anonymous. Above the Bell Company’s dock, Pennsylvania Route 68 invisibly changes to Ohio Route 38, and trees half-hide some signs by the roadside. Even someone familiar with the historical significance of this particular spot, who has travelled several thousand miles to find it, and whose eyes are flickering wildly from the narrow blacktop to the nondescript verge between road and river, can drive a couple of hundred yards past it before hitting the brakes.

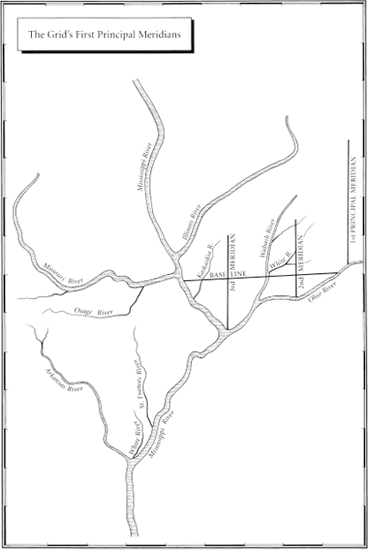

The language of the signs is equally undemonstrative. A stone marker carries a plaque headed ‘The Point of Beginning’ which reads, ‘1112 feet south of this spot was the point of beginning for surveying the public lands of the United States. There on September 30 1785, Thomas Hutchins, first Geographer of the United States, began the Geographer’s Line of the Seven Ranges.’

There is nothing else to suggest that it was here that the United States began to take physical shape, nothing to indicate that from here a grid was laid out across the land that would stretch west to the Pacific Ocean, and north to Canada, and south to the Mexican border, and would cover over three million square miles, and would create a structure of land ownership unique in history, and would provide the invisible web that supported the legend of the frontier with its covered wagons and cowboys, and its farmers and goldminers, and would insidiously permeate its formation into the unconscious mind of every American who ever owned a square yard of soil.

It is hilly country, covered in the same oak, dogwood and hickory that Hutchins saw, and in the bright light of a September afternoon it rises high above the broad river in crimson and copper waves. ‘For the distance of 46 chains and 86 links West,’ Hutchins wrote in his first description of the territory, ‘the Land is remarkably rich with a deep, black Mould, free from Stone.’ He was Robinson Crusoe, landed in an uncharted wilderness, and his purpose was something close to magic – to measure it and map it and turn it into property. It had been lived in by the Delaware and passed through by the Miami and occupied by the Iroquois, but no one had ever owned it. No one had ever thought of owning it. The idea of one person owning land did not yet exist on the west bank of the Ohio.

The wand that would make this magic possible was there in the first sentence of Hutchins’ report. The land would be measured in chains and links. In most circumstances, a chain imprisons; here it released. What it released from the billowing, uncharted land was a single element – a distance of twenty-two yards. That was the length of the chain. Repeated often enough, added, squared and multiplied, the measurement gave a value to the land that could be computed in money terms.

What began here on the banks of the Ohio river was not just a survey. The real significance of the spot now covered by the Bell Company’s concrete dock is that this was where the most potent idea in economic history – that land might be owned, like a horse or a house – was first released into the western wilderness and encouraged to spread across the land mass of the United States. But in his poem ‘The Gift Outright’, Robert Frost caught at a thought more powerful yet. The earth has its own magic, and those who seek to possess it run the risk of being possessed by it. It was the desire to own this particular land, Frost mused, that made its owners American.

These were the great forces that Captain Thomas Hutchins, Geographer to the United States, set in motion when he first unrolled the loops of his chain at the Point of the Beginning.

ONE The Invention of Property

THE IMPOSING LIBRARY of the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors in London is strategically situated. In one direction its tall windows look over the street to Whitehall, where the Tudor and Stuart sovereigns ruled in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and in another they gaze across Parliament Square towards the House of Commons, power-base of the rising class of landed gentry who during those two centuries challenged the royal authority. It is just possible to imagine the atmosphere of righteous indignation and pervading apprehension which accompanied the struggle between the two, but in the small, 450-year-old, leather-bound books kept in the Institution’s library, the reality that gave rise to the battles remains vividly alive.

In the earliest, such as Master Fitzherbert’s The Art of Husbandry, published in 1523, a surveyor still fills his original, feudal role as the executive officer of a landed nobleman. His duty is simply to oversee (the word ‘surveyor’ is derived from the French sur = over and voir = see) the estate. He is to walk over the land, noting the ‘buttes and bounds’ of the tenants’ holdings, and then to assist in drawing up the official record or court roll of what duties they owed. A model report, Fitzherbert suggests, might run like this: the land of a particular tenant ‘lyeth between the mill on the north side, and the South Field on the south, butteth upon the highway, and conteyneth xii [twelve] perches [a perch, like a rod, equals 16½ feet] and x [ten] fote [feet] in bredthe by the hyway, and ix [nine] perches in length, and payeth … two hennes at Christmas and two capons at Easter’.

To ‘butt’ upon something was to encounter or meet it; the alternative word was ‘mete’. This ancient method of surveying, which identified the boundary of an estate by the points where it met other boundaries or visible objects, thus became known as ‘metes and bounds’. Under that title it was to cross the Atlantic to the colonies of Virginia and Carolina and thence to Tennessee and Kentucky, to the confusion of landowners and the enrichment of lawyers.

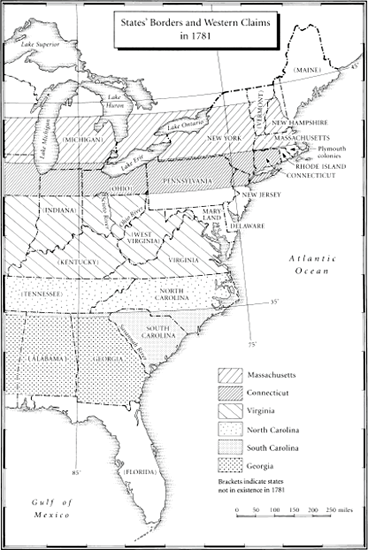

Even in 1523, English landlords were engaged in a practice that was to transform the feudal order. There were infinite variations in feudalism, but at its heart was the principle that the land was the state, and only the head of state could own it outright. The dukes and barons, the king’s tenants-in-chief, technically held their broad acres of the Crown in return for the dues or service they paid; their vassals held their narrower farms from the great lords in return for rent or service; and so on down to the villeins, who had no land at all, but exchanged goods, service or rent for the right to work it. The feudal principle applied equally to the American colonies, whether they were founded by commercial concerns like the Virginia Company, or individual proprietors like William Penn. Every charter authorising the foundation of a colony, from Virginia in 1606 to Georgia in 1732, declared that the land was held of the King ‘as of his mannor of East Greenwiche in the county of Kent, in free and common soccage’ – a term which in fact imposed few obligations, but recognised the feudal framework governing land ownership on either side of the Atlantic. What the sixteenth-century manuals inadvertently reveal, as they detail the surveyor’s duties, is how that order was subverted from within.

Under the old system, tenants farmed narrow strips or rigs of land, often widely separated so that good and poor soil was distributed evenly among those who actually worked the land. For centuries, land-users had attempted to consolidate the strips into single compact fields which could be ‘enclosed’ by a fence or hedge so that crops were not trodden down or herds scattered, but the pattern remained fundamentally intact. Now, however, a period of savage inflation occurred, and in the early sixteenth century every lord and tenant was trying to squeeze the maximum profit from the land. Repeatedly Fitzherbert stresses the need for the surveyor to realise that enclosed land was more valuable than the strips and common pasture because it could be made more productive. The pressure for change is unmistakable, yet essentially the old values are still in place.

Then in 1534 comes the publication of The Boke named the Governour, by Sir Thomas Elyot, which gives advice to ‘governors’, whether of kingdoms or estates, on how to run their ‘dominions’. An essential first step according to Elyot is to draw a map or ‘figure’ of the estate so that the governor knows what it consists of, or as he puts it, ‘in visiting his own dominions, he shall set them out in figure, in such wise that his eye shall appear to him where he shall employ his study and treasure’. In the course of the sixteenth century, it became a habit of English landowners to have their estates and the surrounding countryside measured and then mapped. By 1609 John Norden could insist in the Surveior’s Dialogue that ‘the [map] rightly drawne by true information, describeth so lively an image of a Manor … as the Lord sitting in his chayre, may see what he hath, where and how it lyeth, and in whose use and occupation every particular is’.

There was a particular significance in the surveyor’s new duty of mapmaking, because in that era only the rulers of states and cities made maps. A map was a political document. It not only described territory, but asserted ownership of it. From 1549 a map of Newfoundland and the North Atlantic seaboard of North America detailing Sebastian Cabot’s discoveries used to hang in the Privy Gallery at Whitehall outside the royal council chamber, so that foreign ambassadors waiting to see the sovereign would know of England’s claims overseas. When the Flemish cartographer Abraham Ortelius produced the first modern atlas in 1570, his Theatrum orbis terrarum, which included the freshly discovered territories of the New World and the newly explored Pacific and Indian Oceans, he took care to dedicate it to his sovereign, Philip II of Spain, and to ensure that Philip could find in it his own claims across the ocean.

Consequently, when the sixteenth-century English landowners ordered maps of their estates, they were making a very particular claim. For a long time almost no one but the English made such a claim. Surveying manuals were published in the German states, but there were hardly any estate maps until late in the seventeenth century. Sweden produced her first national map in the sixteenth century, but it was a hundred years later before noblemen began measuring and mapping their estates. In sixteenth-century France, the Jesuits taught maths and all the theory needed by a surveyor, but, as the distinguished historian Marc Bloch noted, no plats or plans parcellaires were drawn before 1650. The first Spanish maps appeared as early as 1508, but no Spanish lords showed any interest in measuring their lands for another two hundred years. Only in the economically sophisticated Netherlands, where the mathematician Gemma Frisius wrote the first manual on mapmaking, A Method of Delineating Places, in 1533, were farms, especially those close to cities, measured and mapped, yet even there the aristocrats’ landed estates remained feudal. But in England, Henry VIII collected so many estate maps that an inventory of his possessions at his death in 1547 showed he had ‘a black coffer covered with fustian of Naples [which was] full of plattes’.

The significance was unmissable. When English landowners commissioned surveyors to measure out their estates and make maps or plats of them, they were asserting a form of ownership that until then only rulers and governors could make.

If there is a single date when that idea of land as private property can be said to have taken hold, it is 1538. In that year a tiny volume was published with a long title which begins, ‘This boke sheweth the maner of measurynge of all maner of lande …’. In it, the author, Sir Richard Benese, described for the first time in English how to calculate the area of a field or an entire estate. He was probably borrowing his methods from Frisius, but his values were purely English. Noting that sellers tend to exaggerate the size of a property while buyers are inclined to underestimate it, he advises the surveyor to approach the task in a careful and methodical manner.

‘When ye shall measure a piece of any land ye shall go about the boundes of it once or twice, and [then] consider well by viewing it whether ye may measure it in one parcel wholly altogether or else in two or many parcels.’ Measuring in ‘many parcels’, he explains, is necessary when the field is an uneven, irregular shape; by dividing it up into smaller, regular shapes like squares and oblongs and triangles it becomes easy to calculate accurately the total area. The distances are to be carefully measured with a rod or pole, precisely 16½ feet long, or a cord. And finally the surveyor is to describe the area in words, and to draw a plat showing its shape and extent.

Like the maps, this interest in exact measurement is new. Before then, what mattered was how much land would yield, not its size. When William the Conqueror instituted the great survey of England in 1086, known as the Domesday Book, his commissioners noted the dimensions of estates in units like virgates and hides, which varied according to the richness of the soil: a virgate was enough land for a single person to live on, a hide enough to support a family; consequently the size shrank when measuring fertile land, and expanded in poor, upland territory. Other Domesday units like the acre and the carrucate were equally flexible, but so long as land was held in exchange for services, the number of people it could feed and so make available to render those services was more important than its exact area. Accurate measurement became important in 1538 because, beginning in that year, a gigantic swathe of England – almost half a million acres – was suddenly put on sale for cash.

The greatest real-estate sale in England’s history occurred after Henry VIII dissolved a total of almost four hundred monasteries which had been acquiring land for centuries. He justified his action on the grounds that these houses of prayer had grown depraved and corrupt, but tales of drunken monks and lecherous nuns served to conceal a more mundane purpose – Henry needed money. On the monasteries’ dissolution, all their land, including some of the best soil in England, automatically reverted to their feudal overlord, the king. These rich acres were then sold to wealthy merchants and nobles in order to pay for England’s defences.

The sale of so much land for cash was a watershed. Although changes were already underway, with feudal services often commuted for rents paid in coin, and feudal estates frequently mortgaged and sold, up to that point the fundamental value of land remained in the number of people it supported. From now on the balance would shift increasingly to a new way of thinking. Prominent among the purchasers of Church property were land-hungry owners, like the Duke of Northumberland, who had been enclosing common pastures, but far more common were the small landlords who had done well from the rise in the market value of wool and corn, and who now chose to invest in monastery estates. In Norfolk, Sir Robert Southwell attracted attention because of the mighty pastures he carved out from common land for his fourteen flocks of sheep, each numbering around a thousand animals, but the Winthrop family who acquired and enclosed monastery land in the same county almost escaped notice.

They and their surveyors knew that the monasteries’ widely separated rigs and shares of common land would become more valuable once they were consolidated into fields. It was what later generations would term an investment opportunity. The old abbots and priors had understood land ownership to be part of a feudal exchange of rights for services. The new owners knew that it depended on money changing hands, and that to maximise profits the old ways had to be replaced.

‘Jesu, sir, in the name of God what mean you thus extremely to handle us poor people?’ a widow demanded of John Palmer, an enclosing landlord in Sussex who in the 1540s bought the monastic estate on which she lived, and evicted her from her cottage.

‘Do ye not know that the King’s grace hath put down all the houses of monks, friars and nuns?’ Palmer retorted. ‘Therefore now is the time come that we gentlemen will pull down the houses of such poor knaves as ye be.’

As enclosures and rising rents forced thousands of villeins and farm-labourers away from the manors that once supported them, protests kept the printing presses busy. Some represented the propaganda of conservative voices like Sir Thomas More, who memorably wrote of pastoralists like Southwell, ‘Your sheep that were wont to be so meek and tame, and so small eaters, now as I hear say, be become so great devourers and so wild, that they eat up and swallow down the very men themselves.’ Resentment also triggered popular uprisings in the north, east and west of England, and the government itself introduced Bills in Parliament against enclosure, though by the second half of the sixteenth century few were passed.

Recent research downplays the actual number of enclosures, but no one questions the enormous redistribution of land that occurred. Even G.R. Elton, the most sceptical of Tudor historians, accepted that it ‘laid the foundation for that characteristic structure of landlord, leasehold farmer, and landless labourer which has marked the English countryside from that day to this’.

The hidden hand in this gigantic upheaval was provided by the survey and plat that recorded the new owner’s estate as his property. The emphasis in Benese’s book on exact measurement reflected the change in outlook. Once land was exchanged for cash, its ability to support people became less important than how much rent it could produce, and that depended largely on the size of the property. The units used to measure this could no longer vary; the method of surveying had to be reliable. The surveyor ceased to be a servant, and became an agent of change from a system grounded in medieval practice to one which generated money.

Some at least became uneasily aware of what they were doing. In the Surveior’s Dialogue, John Norden specifically blamed the act of measuring itself for helping to destroy the old ways, and held surveyors responsible as ‘the cause that men [lose] their Land: and sometimes they are abridged of such liberties as they have long used in Mannors: and customes are altered, broken, and sometimes perverted or taken away by your means’.

What the new class of landowners required of their surveyors above all was exactness, and the sudden increase in the number of manuals the last quarter of the sixteenth century testified to the urgency of their need. Before that, in 1551, Robert Recorde wrote a book called Pathway to Knowledge in praise of the accuracy that geometry offered surveyors, but warning of its potential for destruction:

Survayers have cause to make muche of me.

And so have all Lordes that landes do possesse:

But Tennauntes I feare will like me the lesse.

Yet do I not wrong, but measure all truely,

And yelde the full right to everye man justely.

Proportion Geometricall hath no man opprest,

Yf anye bee wronged, I wishe it redrest.

It was against this background – an urgent and growing need for the accurate measurement of land – that Edmund Gunter devised his chain. Born in 1581 to a Welsh family, Gunter had been sent to Oxford University to be educated as a Church of England priest, but by the time he was ordained he had discovered that numbers were more inspiring to him than religion. In twelve years as a divinity student he preached just one sermon, and its reputation endured long after his death because, according to Oxford gossip, ‘it was such a lamentable one’. What really interested him was the relationship of mathematics to the real world, and consequently he spent most of his time making instruments to illustrate the way in which numbers worked.

Ratios and proportions were his passion. He invented an early slide-rule, known as Gunter’s scale, to demonstrate proportional connections between numbers, and worked out to seven places of decimals the logarithms for sine and cosine. The point at which this enthusiasm for numerical ratios touched upon concrete reality was trigonometry, which allowed mathematicians to calculate the length of two sides of a triangle, when only the third side and two angles were known; it also, as we have seen, enabled surveyors to work out the distance between two objects without having to walk between them.

Since only the most basic instruments existed at that time, mathematicians and astronomers were expected to design their own. To demonstrate the solutions to problems in geometry, Gunter was constantly adapting and improving nautical instruments like the quadrant and cross-staff, which measured vertical angles between the sun and the horizon, or horizontal angles between towers, trees and churches. Indeed his enthusiasm for new gadgets cost him the best scientific job in the land. In 1620 the wealthy but earnest Sir Henry Savile put up money to fund Oxford University’s first two science faculties, the chairs of Astronomy and Geometry. Gunter applied to become Professor of Geometry, but Savile was famous for distrusting clever people – ‘Give me the plodding student,’ he insisted drearily – and the candidate’s behaviour annoyed him intensely. As was his habit, Gunter arrived with his sector and quadrant, and began demonstrating how they could be used to calculate the position of stars or the distance of churches, until Savile could stand it no longer. ‘Doe you call this reading of Geometrie?’ he burst out. ‘This is mere showing of tricks, man!’, and according to a contemporary account, ‘dismisst him with scorne’.