Полная версия

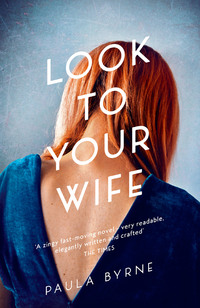

Look to Your Wife

Edward and Lisa had their honeymoon in Venice. They stayed in a hotel on the Grand Canal opposite the Ca’ d’Oro. Lisa loved the ‘Golden House’, which she could see from their bedroom window, so-called because of the gilt that adorned its façade. They woke in the morning to the cries of the gondolieri, and the splash of boats carrying their wares in the early morning sunshine. At that time of day, the sun was not yet shining on the Ca’ d’Oro, so it was more putty-coloured than golden, but that would change with the afternoon sun, and then it would glow and shimmer, casting its gorgeous reflection on the glassy green waters below. Narcissus in love with its own dazzling, dizzying beauty.

Venice was the city that ignited Lisa’s passion for food. After Edward, it was her most enduring love affair. It was early September, just before the start of term, and the restaurants were not so crowded. She made friends with the cameriere at Al Mascaron in Santa Maria Formosa. He recommended the stuffed pumpkin, then risotto ai funghi with rocket and warm bread. They drank chilled Prosecco and then Refosco from the demijohns that lined the wooden bar. The cameriere brought figs and pears in a bowl of iced water. When she asked him to point out the locals, he told her that Venetians mainly eat at home, but buy bread at the panificio and pudding at the pasticceria, where, he said, you can also buy biscotti al vino, tiny plum tarts, and almond cornetti.

The next morning, whilst Edward slept late, Lisa wandered to the Rialto, home to the famous food market. She failed to find Shylock, but she saw wreaths of onions, bunches of aromatic herbs, late-ripening San Marzano tomatoes and bulbous glossy purple melanzane. Then, next to the fresh market was the pescheria, fish pulled straight from the Adriatic, squid, soft-shelled crabs, writhing eels, swordfish and tuna. The macellerie, where rabbits hung from hooks, and steaks and chops lined the tables.

Lisa did not speak Italian, unlike Edward who was fluent and spoke the language like an ambassador, but she understood when the market farmers proffered shards of melon, and warm figs, ‘Tasta, tasta bea mora.’ She stopped off at a bar and ordered a cappuccino. Even in the morning, the local people swigged glasses of Prosecco and gulped down espresso in one go; the Italian way.

The next morning she headed to the market on the Lido, not to buy, but to look at the rolls of damask, cappuccino-coloured, bolts of creamy silk, embossed linen napkins.

When she got back, Edward was showered and ready to explore. He wanted to show Lisa the Carpaccios at the Scuola di San Giorgio degli Schiavoni.

‘Main course, or starter?’ she teased.

Edward laughed.

‘Well, coming from the girl who’s currently reading the high-brow, literary thriller Gondola Girl, nothing surprises me.’

‘I’m also reading The Wings of the Dove,’ Lisa protested.

Edward never read trash. He only read improving books.

‘Shall we take the vaporetto, or walk?’

‘Let’s walk.’

Edward was happy showing Lisa his beloved Carpaccio painting of St George and the Dragon. Lisa was surprised by his choice. St George astride his stallion; his long, silky blond hair streaming behind him, his lance poised to strike. She didn’t like the picture; it reeked of violence and destruction. He saw the patron saint of England valiantly fighting the dragon, she saw toads and snakes, vipers, lizards. Then the dead bodies, a woman’s torso, still clad in a half-devoured dress, severed arms and legs. Why did he love this so much? She wondered about this side of Edward; a side she didn’t really know.

‘That spear’s rather phallic,’ she joked.

‘The whole thing is beautiful, astonishing.’

Lisa was glad of the cool, a respite against the burning heat of the day. She lingered to buy a postcard. It was time to tell her parents that she had quietly remarried.

‘Let’s find a bacari. I’m desperate for a drink. Edward, it’s my honeymoon.’

Edward disapproved of lunchtime drinking. He could be such a Puritan. He liked breakfast, lunch, afternoon tea, supper. Sometimes, when she offered him an early aperitif, he would say that he’d prefer a cup of tea. He would drink two glasses of wine over supper. He never liked to feel out of control.

As they walked along the Salizada Sant’Antonin, Lisa spotted a dress shop called Banco Lotto n. 10. In the tiny window was a beautifully cut cashmere coat. There was a notice pasted on the door saying that the clothes sold inside were made by the female prisoners of the Casa di Reclusione Femminile. Lisa pushed the door open and walked in. The woman behind the counter spoke English, and she explained that the Guidecca’s Women’s Prison was situated behind the walls of a former thirteenth-century convent. There were about eighty inmates who ran a tailor’s workshop and then sold their goods in the little shop. Even Edward was intrigued.

There were rails of organza dresses and coats, hats and scarves. Lisa bought a couple of silk scarves and the cashmere coat. She vowed to herself that she would try to discover more about the prison workshop and the women who made these beautiful clothes. Maybe she could write an article about it for Textiles magazine.

That evening, Edward and Lisa went to the Teatro la Fenice. Chuck had made them promise to go to the theatre, as it was one of his favourite opera houses in Europe. They had smiled when they heard that Verdi’s Otello was being performed. They decided to dress up for the occasion. Edward wore black tie, and Lisa a backless Helmut Lang maxi dress of black, draped jersey. As Chuck had predicted, the theatre was indeed fabulous, if baroque was your thing. The gilded private boxes and crimson velvet seats, and the painted ceiling were opulent, though it was not Lisa’s aesthetic. Edward looked happy; he was glowing, and looked so handsome in his dinner jacket and bow tie.

The opening was spectacular. The Cypriot crowd anxiously waiting for Otello’s ship to come in, singing the storm in a swell of percussion and brass. There was Desdemona, wearing a fish-net veil over her bright blonde hair, peering out looking for her husband, and then, there he is, the crowd are giving thanks and rejoicing. But something is wrong. Lisa sensed her husband stiffening beside her. His mouth was set in a hard line, his eyes angry.

‘We’re leaving,’ he whispered.

Thank heavens they were sitting in the end seats. It was bad enough enduring the black looks of the audience as they left, without having to squash past a line of angry Venetians.

Once outside in the balmy air, Lisa learned what had upset Edward. He spoke quietly, calmly.

‘He was blacked up. Can you believe it? I thought they’d put a stop to all that. It’s fine for a white man to play Otello, but why cover his face in soot? We’re supposed to be colour-blind.’

‘Edward, I barely had time to notice before you dragged me out. I understand why you’re upset, but shouldn’t the best singers have the best roles?’

‘Yes, of course, but, for God’s sake, it looked like shoe polish on his face. He looked absurd. And Verdi’s Otello is not particularly interested in race. Otello is the archetypal jealous Italian husband.’

At that very moment, a gorgeous black man in a sharp suit walked past them, looking every inch as if he’d just walked out of Shakespeare’s imagination. He gave a barely perceptible nod in Edward’s direction, and an appreciative glance at Lisa. She was mesmerized.

‘Crikey, look at him, why didn’t they drag him off the streets and into the theatre!’

They both burst out laughing, and the tension dissipated. Edward smiled and enveloped her in his arms. He gently kissed the top of her head. They walked home to bed.

CHAPTER 5

‘I’m Going to Rescind that Ticket, Sir’

The postcard of St Augustine in his study with his little dog, sent from Venice, was signed Mr and Mrs Chamberlain. Lisa waited for the storm to break. Her mother wanted the details. She tried not to feel disappointed that her daughter had married in a register office. Lisa told her that she didn’t want a fuss. She told her mother that after the ceremony, they ate thin slices of veal, sipped champagne, and gorged on confectionary from a corner shop. It was exactly how she wanted it. Her mother forgave her, even though she knew that the Pope wouldn’t. She had always worried that there weren’t going to be grandchildren with Pete, and she had a mother’s instinct that it would be different this time around.

Lisa was pregnant when they returned from the honeymoon. They called their daughter Emma.

Lisa loved her with a visceral passion and ferocity. She herself was born in August, a Leo, and although she didn’t hold much faith in astrology, she was a lioness through and through. She had flaws aplenty, but she also had loyalty and courage in spades. Her revered Coco Chanel was a Leo too, and collected lions, and used them again and again in her work. Lions embroidered onto bags, costume jewellery, even jackets.

It had been a tricky start to motherhood, however. Emma was premature and tiny. Her lungs were not developed, so she was whipped away into intensive care before Lisa could bond with her. There was a terrible moment when she experienced a fleeting desire to grab the baby and smash its tender skull on the hard hospital floor. The feeling went as quickly as it came, but it horrified Lisa. Is this how an animal feels when confronted with the runt of the litter? It was a Lady Macbeth moment. She dared not tell a soul, not even Edward, who understood her so well, and would never judge. She felt a deep sense of shame.

The love for baby Emma came later, but, when it did, it was all-encompassing. It was the truest, purest, love of her life. Emma was her Achilles’ Heel. She would die for her. The difficult first few months – Emma in an incubator, with the only possible contact through a tiny finger-hole in the Perspex casing – brought her close to Chuck, who had by now been promoted to deputy head. He had become Edward’s trusted confidant.

Chuck had lost a baby. A boy. The baby had been three weeks old when he and Milly found him lifeless in his cot. Cold as any stone. Chuck – smart-talking Chuck, the coolest dude to come out of South Carolina – still cried when the boy was mentioned. His marriage to Milly had foundered under the strain, though they would always remain the best of friends. Milly ran a small local charity for battered wives. Edward arranged for it to be the school charity, supported by cake-sale days, and sponsored walks along the banks of the Mersey.

Some of Lisa’s colleagues disliked Chuck: he was too American, too forthright, too clever. But she knew what he had suffered. She sympathized, and he in turn revealed a tender side as baby Emma struggled to pull through those first weeks.

Despite this, Lisa was never entirely sure that Chuck could be trusted. Soon after arriving at St Joseph’s, she had been warned by a colleague to be wary of him.

‘Do you know what he said about you?’

‘No, Jan, and I’m not sure I want to. I’m insecure enough as it is.’

‘Well, I’m going to tell you because he’s no friend to you. He doesn’t like women, Lisa.’

‘What do you mean? He’s not gay. No one has a better gaydar than me. Go on then, what did he say?’

‘Well, it was at your book launch party. Someone asked for you and he piped up, “You can’t mistake her. She’ll be the one with her tits hanging out of her designer dress”.’

Lisa chuckled. ‘Oh come on, Jan. That’s the way he speaks. He means no harm. He’s just joking. You know he’s got a thing about breasts, because his wife is so flat-chested.’

‘Well, look at the way he dressed for your party, in all that combat gear and muddy boots. Why would anyone turn up to a party celebrating a book about fashion looking like that? It was a deliberate slap in the face. He doesn’t like you, Lisa. I see the way he watches you all the time.’

* * *

Emma wasn’t very lucky with her health. The under-developed lungs had consequences. Apnoea episodes in the night. Parental panic. More than one 999 call. The hospital became a familiar place.

Clinics, scans, tests. And then, during what was supposed to be a merely precautionary ultrasound, the radiographer said, ‘Something’s not quite as it should be here. Can you wait a minute while I consult a colleague?’

A more senior-looking figure came in, holding the printout of the ultrasound. ‘Nothing to worry about, but just to make sure, we’re going to admit Emma to hospital down in Birmingham where they specialize in this area.’ They refused to say exactly what was wrong, only that when a young child’s lungs struggle, it was important to keep an eye on the heart. ‘Let’s leave it to the experts in Birmingham.’

‘How do we get there?’ asked Lisa. ‘On the train?’

‘No, we’ll take her in an ambulance – just to be on the safe side. Maybe call your husband and get him to drive down and meet you? Nothing will happen before he gets there. It’ll probably be a day or two before they complete the necessary tests.’

‘You’re one of the Heart Kids now,’ one nurse joked, as little Emma was admitted onto the ward. A Heart Kid, thought Lisa, as if that were a good thing. You had to laugh or you’d go mad. Soon, Emma was hooked up to an array of machines, and a whole team of doctors was standing over the bed. And then Lisa heard words that no parent should ever hear: ‘Your daughter is in serious danger of heart failure. We are going to have to perform bypass surgery. Immediately.’ A ‘nil by mouth’ sign was hung up in preparation for surgery.

Broken hearts, Lisa thought. Men and women whine on about broken hearts. Narcissists. Know what it’s like to have a consultant tell you that your child needs bypass surgery. The kind of thing you associate with old men whose arteries are clogged. A child in intensive care. That’s a broken heart.

Edward fell apart when she telephoned him. He cried and he cried. No time for tears, thought Lisa. Get this girl through the operation. She sat at Emma’s side, holding her hand, as she waited and waited for her to be taken into theatre, willing her to survive. I can be the mother of a sick child, she thought, but God please spare her. She was reassured when the surgeon came to speak to them. He told her that heart bypass surgery, even for children, was a routine procedure these days. ‘No different from having your tonsils out in the old days when you were young,’ he grinned, slightly flirtatiously. She didn’t believe him, but she liked his style. He looked alarmingly young to be performing heart surgery. He had blond, floppy hair, and was wearing DM boots. He’s OK, Lisa thought. A surgeon in DM boots is going to save my child. And he did. She never doubted him.

On coming round from the anaesthetic Emma cried silent tears and tried to mouth the word ‘Mummy’. From that moment on, Lisa knew she was going to be all right. She was strong, like her mother. No one likes a child who screams and throws a tantrum, but a child who is trying not to cry, when she has had major heart surgery … well, that was courage.

Edward had only just made it down from Liverpool to Birmingham in time for the operation. When Lisa had called him, he had been in a tricky meeting, and he’d seen it through to the finish before setting off. He was always the professional. When he arrived, Lisa shouted at him, accusing him of caring more about the bloody school than his own daughter. ‘Don’t worry,’ he said, ‘I’m here now.’ Though he’d only made it in time by virtue of driving the wrong way down the one-way street outside the hospital and parking in a direction that revealed his transgression.

When he emerged into daylight, after the long night waiting in the parents’ room while the surgery was taking place, then the relief of stroking Emma’s hair in the recovery room, he found a yellow ticket on the windscreen of the BMW. His head throbbing with fury, he stalked into the police station that happened to be opposite the children’s hospital. He had a thing about the police. He had been incandescent on the occasion that he had been pulled over in Toxteth, just because he was driving a black BMW. He demanded to see Officer 354, who had issued the ticket, explaining through gritted teeth that his young daughter had just gone through open-heart surgery.

The constable looked visibly taken aback, and said, ‘I’m so sorry to hear that, and in the circumstances I’m going to rescind that ticket, sir. And I do hope your daughter makes a full recovery.’ She did, and somehow his faith in human nature, even in God, was restored by the policeman’s evident delight in the opportunity to use the word rescind.

Having come close to it, Lisa knew that there could be no pain in the world like losing a child. Once it was clear that Emma had got through the operation without infection or complication, she was moved from isolation to a ward. One evening, Lisa saw a tiny premature baby boy in a side room. The door was ajar, and she overheard family members saying platitudes to the mother like ‘he’s a little fighter’, ‘he looks stronger today’, ‘you’ll be home before you know it’. But when Lisa looked at the father’s pale, pitiful face, she knew that he knew the truth. At least her daughter was still alive. She thought of Chuck that day, and the hell that he had endured.

In the months following Emma’s recovery, Lisa became desperate for another baby. Edward had always insisted that he only wanted one child. That was his own experience. ‘Have two and it will soon be three,’ he said. ‘And then you lose your man-to-man marking capability.’ And again, ‘If there are three, one child will always feel left out – and then you’d have to buy a people carrier, get an extra bedroom on holidays.’ His other worry was Emma’s health. What would happen if she needed another heart operation, if there were a new baby in the family?

‘I’m not talking about six children, like in my family, darling. Not even about three. Just one more.’ Lisa was not to be deterred, and Edward believed her when she said that she could cope just fine. Her strongest argument was her concern that their home life would be dominated by Emma’s poor health. What could be more distracting, more lovely, than a baby in the house? The milky, yeasty smell of a new baby. Then, as Emma began at school, a toddler making them all laugh.

Edward never really had a choice. When a woman wants a baby, nothing or no one will stand in her way. Emma told her colleague Jan about her plan to become pregnant. She had conceived easily the first time. She had no worries on that score. ‘Tonight’s the night,’ she said. ‘The champagne’s in the fridge, and I’m going to seduce my husband.’ Three months later, she told Jan that she was having a baby, a boy. They both giggled conspiratorially. ‘I always knew you were a determined woman,’ said Jan, admiringly.

Emma was delighted to know that her mother was having a boy baby. Lisa told her, ‘He’s yours. I had him for you.’ She wanted something good to come out of the sadness of Emma’s health problems. She had secretly longed for another daughter, but little Emma much preferred the idea of a brother.

Emma was special. One day when Lisa was heavily pregnant and climbing the stairs, she felt two little hands underneath her belly, lifting up the weight. The support felt fantastic. During the early part of the labour, Emma came into the hospital ward and encouraged Lisa to walk around and work through the pain. Much to Lisa’s amusement, Emma found a large pink plastic ball in the maternity suite and rolled it towards her.

‘Em, how on earth do you think that exercise ball is going to help?’

‘Sit on it, Mummy. Then your back won’t hurt.’

It worked like magic.

Because Emma had been premature, Lisa had been told to have an epidural. There had then followed a messy forceps delivery. This time, she wanted a natural birth. She wanted to know whether physical pain could be as bad as her mental anguish over Emma’s heart condition. Nothing could be worse than almost losing her daughter. Physical pain is physical pain and could be endured. Perhaps she was punishing herself. She wasn’t entirely sure about her motives, and the pain was excruciating. It was Edward who got her through it.

‘You can do it. You can do it. I know you can.’

That was all she needed to hear. Afterwards, she was too exhausted to take the baby in her arms. She told the nurse to give the baby straight to Emma. Job done, she told herself, as she saw Emma’s happy, excited face. Lisa fell asleep.

Emma was only five when he was born, but she carried George around the house as if he were a doll. Lisa’s girlfriends were amazed that she let Emma carry the baby in her arms over the flagstone floors of their farmhouse – having married, recovered from the financial clean-out of their respective divorces, and had a family, they had moved out of the city to a village in Cheshire. After the trauma of Emma’s first few months of life, Lisa had decided that she would only go back to her textiles GCSE class part-time. With the arrival of George, she decided to give up teaching altogether. She might finally have some time for that second book.

‘Aren’t you scared that she’ll drop him? She’s only a child herself.’

‘She won’t drop him. There’s more chance that I would drop him than that Emma would. He’s too precious.’ And she never did.

* * *

Over the years, Chuck always offered support through the difficult times. Once, when Edward and Lisa had returned home after several days and nights in hospital with Emma, who had come down with a serious infection, they had found, waiting on the kitchen table, a Fortnum and Mason hamper of goodies and a huge vase of blue cornflowers. A stew in a brand new Le Creuset casserole dish was warming in the Aga, and the lawn was freshly mown in neater stripes than Edward had ever achieved. Chuck had arranged it all, liaising with one of their neighbours, who had a spare key to their house.

Touched by such gestures, Lisa and Edward asked him to be George’s godfather. Lisa also hoped that it would help him to have a child in his life. Chuck took his godparenting duties seriously. He gave generous and thoughtful Christmas presents, and said that he would lay down a bottle of the best Californian red wine every year so that George would have his very own cellar when he was eighteen.

CHAPTER 6

Missy

Lisa kept saying that she had had enough of teaching. Apart from Jan, she didn’t get on with the other women in the staff room. Especially not with Ms Robinson. There was history between them.

Misan Robinson was formidable. Most people at SJA were terrified of her. She was so right-on, with her dreadlocks and her Adidas trainers. The students respected Missy. There was no messing about in her classes. She taught religious studies (even though she was an atheist). Her special interest was in feminist theology. She worshipped Rosemary Radford Ruether. Her dream in life was to teach at Howard University, and, to that end, she had enrolled on an MA programme at the Open University. Missy had a dream.

Lisa could not stand Ms Robinson. She was so pretentious, so achingly cool. What a phoney. Edward, of course, loved Missy. This was one of the rare instances when he and Lisa did not agree.

‘She’s exactly what this school needs. Know your privilege, Lisa.’

‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

‘You know exactly what I mean.’

‘Do you fancy her?’

‘Don’t be absurd. She’s a first-class teacher, and a team player. You don’t make any effort to win her over.’