Полная версия

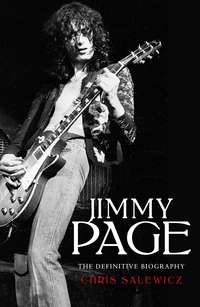

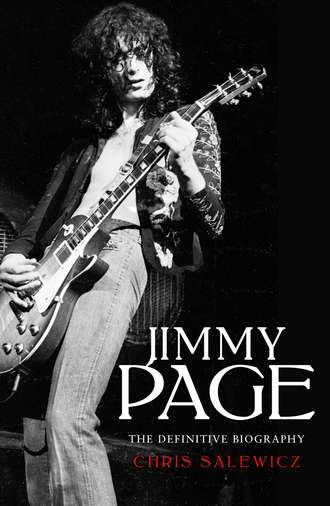

Jimmy Page: The Definitive Biography

Jimmy Page and Donovan Leitch were like-minded musical souls, each with their own interest in metaphysics. Playing on ‘Sunshine Superman’ with Page was – yet again – John Paul Jones on bass. At those same sessions Page played the haunting guitar on Donovan’s equally memorable ‘Season of the Witch’, which was on the Sunshine Superman album. Built around a D ninth chord shown to Donovan by master guitarist John Renbourn, ‘Season of the Witch’ was ideal for extended versions and would be frequently employed as soundcheck material by Led Zeppelin.

Back in the UK, Jeff Beck’s health returned, and he drove over to Page’s Pangbourne home, its interior design already beginning to reflect the prevailing rock-star rococo style. The two guitarists worked out a stage routine that would allow each to play lead guitar, intertwining with one other and mutually strengthening their playing and that of the group. Among the songs they developed was a version of Freddie King’s ‘Goin’ Down’ – though this was never recorded.

They needed to work fast. On 23 September the Yardbirds again hit the road, supporting the Rolling Stones and the Ike and Tina Turner Revue on a 12-date tour of the UK, two shows a night, ending on 9 October 1966.

The tour kicked off at London’s Royal Albert Hall, where the Yardbirds allegedly blew the Rolling Stones off the stage. Yet the review they received from the NME, especially for Jeff Beck, was extremely sniffy; it irritated him that he was described as ‘a guitar gymnast’. Simon Napier-Bell utterly disagreed with such an assessment: ‘They were really fantastic. What Jeff and Jimmy were doing was playing Jeff Beck’s solos, but in harmony. It was astonishing to hear, and to watch.’

Difficulties soon arose, however. According to Chris Welch in Led Zeppelin: The Book: ‘One problem was that Jeff couldn’t handle the competition and would try to blow Jimmy off the stage. Page was always on the ball, but Jeff’s returning fire in guitar exchanges would be unpredictable and relied on volume when accuracy failed.’ Napier-Bell was in agreement in an interview he did with Jim Green in the October 1981 edition of Trouser Press: ‘Jimmy deliberately upstaged Jeff, Jeff got moody and walked out towards the end, fortunately we finished it.’

Quickly forgiven, Beck was admitted back into the Yardbirds fold. This was a necessity, as they were about to join the winter leg of Dick Clark’s Caravan of Stars – a regular feature of the American popular music calendar organised by the legendary DJ. But before that there was another avenue to explore.

An exaggerated, dramatised version of the high-end hippiedom found at Anita Pallenberg and Brian Jones’s home was expressed in the party scene in the classic – yet occasionally extremely pretentious – metaphysical thriller Blow-Up, which Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni started filming in London in April 1966. (The scene was actually shot in Christopher Gibbs’s Cheyne Walk house.) In the film a fashion photographer, played by David Hemmings and clearly based on enfant terrible David Bailey, thinks he has witnessed a murder.

After completing the London shoot in June, Antonioni decided that to fully represent the capital’s glamorous, swinging spirit he should shoot a sequence in a rock ’n’ roll club. In September he returned to London and booked a meeting with Kit Lambert, manager of the Who. The day before the meeting, Lambert had lunch with Napier-Bell at the Beachcomber restaurant in London’s Mayfair Hotel; the two men were close friends and Lambert wanted to pick Napier-Bell’s brain about how to approach Antonioni. Napier-Bell decided to set him up to the advantage of his own group: ‘I told him to ask for £10,000 and insist that the Who had final edit on their sequence. Antonioni kicked him out after about a minute.

‘Then I went to see Antonioni: “We don’t want money. This is art. Of course I don’t want to edit it.”’ (In fact the Yardbirds received £3,000 for their part in Blow-Up: car-freak Jeff Beck immediately spent his share on a second-hand Corvette Stingray.)

Napier-Bell had scored. The Yardbirds’ Blow-Up sequence was filmed at Elstree Studios in Borehamwood, north of London, doubling for Windsor’s hip Ricky-Tick Club, in the week beginning 6 October 1966. The band played ‘Stroll On’, as it was called in the film’s credits, the lyrics having been rewritten the previous night by Keith Relf for copyright reasons – in other words, so he could snatch the credit. But it was better known by fans who had experienced the song when rivetingly performed by the Johnny Burnette Trio as ‘Train Kept A-Rollin’’ – the same song that the Yardbirds had recorded at Sun Studio in Memphis the previous year. (Howlin’ Wolf’s ‘Smokestack Lighting’, a Yardbirds live favourite, had been first choice, but the idea was shelved when Antonioni decided it lacked the relentless pace he needed for the scene.)

‘Train Kept A-Rollin’ would be the very first number that Led Zeppelin would play in their initial rehearsal; in Blow-Up the Yardbirds essay an angry, explosive version of the song before a consciously static audience, which includes a young Michael Palin and a dancing, silver-coated Janet Street-Porter. Page stands stage-right to Beck’s stage-left and, rather in the manner of the Kinks’ Dave Davies, his hair is parted in the centre, his mutton-chop sideburns kissing his jawline and peeking out beneath the twin tonsorial curtains waterfalling from his head. He wears an open black jacket, a trio of badges balanced symmetrically on each lapel. In the sequence Beck freaks out over a malfunctioning amp, smashing his guitar to splintered pieces in a manner that only Pete Townshend would actually do in reality. Upon learning of his role, Beck had recoiled: would he have to destroy his new Gibson Les Paul? No fuckin’ way!

A bunch of cheap Höfner replica guitars were brought in. ‘Jeff Beck had to be coaxed into smashing the guitar. And then he did it half a dozen times,’ recalled Napier-Bell. It is only after the guitar has been destroyed that the audience breaks out into a feverish response.

Smashing the guitar wasn’t the only problem Beck had on the film, however. ‘Antonioni was a pompous oaf. I didn’t like him at all,’ he said. ‘The film was a bit of a joke. Crap. I thought, “Oh, that’s the end of us.” Because I saw the premiere in LA. But people loved it. It kept us going.’

This scene from Blow-Up appears to be the only filmed record of Page and Beck playing together in the Yardbirds. Though he is only briefly glimpsed in this scene, and Beck’s thuggish fury unquestionably steals their joint screen time, Page’s almost girlishly pretty looks – which crease momentarily into a smile – contrast powerfully with Beck’s pugnacious posture, like that of a yob awaiting his borstal sentence. You can see why, for the brief time they played together, the pair proved such a potent force in the Yardbirds.

Along with the Yardbirds on the Dick Clark Caravan of Stars tour were bill-toppers Gary Lewis & the Playboys, whose singer was the son of comedian Jerry Lewis. The group – safe in a Herman’s Hermits/Gerry and the Pacemakers kind of way – had seven successive US Top 10 singles. Then there were ‘Wooly Bully’ hitmakers Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs; the Distant Cousins; Bobby Hebb, high in the US charts that summer with his sophisticated, sexy ‘Sunny’; and early sixties vocal star Brian Hyland, purveyor of puppy-love pop. Soon, as album rock became the principal market force, several of those acts would see their careers nosedive forever.

The tour wound through the south, the Midwest and East Coast before winding up in Huntington, West Virginia, on 27 November. ‘Thirty-three dates, I think, and of those twenty-five were doubles, two shows in one night,’ said Page. ‘You’d think a double would be played in the same town, but it wasn’t – it was two different towns. The show was in two halves. When the first half finished, and there was an interval … the performers would get on the coach driving to the next venue, while the second half carried on. Then, they in turn carried on to the next place, where the others had by then finished. It was the worst tour I’d ever been on, as far as fatigue is concerned. We didn’t know where we were or what we were doing.’

Travelling conditions were abysmal, the artists being driven 600 miles or so a day in a pair of converted Greyhound buses to play four songs each at every show. ‘The other acts had little or nothing in common with us,’ said Jim McCarty. ‘Sam the Sham and his Pharoahs, Brian Hyland. I mean, they were just so different, though Sam the Sham had his moments. Anyway, when they let us off the bus, we’d go onstage and they’d shout, “Turn the guitars down!” Jimmy was getting through it because he was a professional. Chris and I stood up to it because we were creating humour from all sorts. Keith was drinking his way along. But Jeff …’

Jeff Beck was becoming a specialist in crossing the United States in a bad mood: ‘The bus was supposed to have air-conditioning, but didn’t seem to. And all the American groups on the bus played their guitars non-stop, and were always singing. Could you imagine? Cooped up on a stuffy bus with everyone around you singing Beatles songs in an American accent?’

His technique honed on the set of Blow-Up, Beck cut a destructive swathe through the tour’s initial dates: amps thrown out of windows, instruments smashed. ‘Jeff Beck had to be coaxed into smashing his guitar for the Blow-Up scene,’ said Napier-Bell. ‘And then he fell in love with doing it and with smashing his amp. I’m sure Jimmy Page was counting the nights, because then Jeff Beck left.’

The frustration within the group began to mount, and, as Beck would admit in hindsight: ‘I was quite messed up. At 21 I was really on my last legs. I just couldn’t handle it.’

‘One time in the dressing room,’ recalled Page, ‘Beck had his guitar up over his head, about to bring it down on Keith Relf, but instead smashed it to the floor. Relf looked at him with total astonishment, and Beck said, “Why did you make me do that?”’

In the middle of the tour, in Harlington, Texas, Beck caught a taxi to the airport and flew to Los Angeles – where, of course, Mary Hughes awaited him. Beck’s explanation for his departure? A return of his chronic tonsillitis. He was going to have treatment and would soon return, he said.

The day after Beck disappeared, Napier-Bell was obliged to appear on a local television show to announce that the next Yardbirds concert had to be cancelled. Showing that they were perfectly adaptable under stress, Relf and Page scoured the area for a joke shop. When Napier-Bell took a lengthy pull on the cigar his pair of charges had presented to him, he had to jump back as it exploded in his mouth – in the middle of the live television broadcast. At the time there was a term for such behaviour among UK groups: looning. Page’s part in this moment clearly showed that he was not above indulging in this, although, given the complicated relationship he had with his manager, was there a subconscious maliciousness in the very notion of this deed?

Once again, Page took over as the sole lead guitarist. ‘Jimmy was always a real pro,’ said Chris Dreja, ‘whereas Jeff was a man of emotion. I think Jeff always found it harder than Jimmy because he was prone to playing according to how he felt, whereas Jimmy’s idea was always, “We’re professional entertainers.”’

‘I didn’t like my territory being encroached upon, and I wanted to be it, to do all the guitar playing,’ admitted Beck. ‘And when it got to the point when I was exhausted, we then embarked on a six-week Dick Clark tour. Six hours in that thing was enough for me. To be faced with those kind of travel problems and emotional tear-ups, and you’d get to the end and play a toilet gig with music you didn’t feel comfortable with, was a recipe for disaster. Things just got on top of me and I cracked up, basically. I wanted to do something other than travelling … So it’s not important whether I was kicked out or I left – it just happened.’

After a period of reflection in Los Angeles, Beck attempted to return to the Yardbirds. He realised that he had essentially been suffering from a minor nervous breakdown. But when word got back to the Yardbirds that their AWOL guitarist had been seen enjoying himself in LA nightclubs, they voted Beck out of the group.

‘That was the point at which I gave up on trying to manage the Yardbirds,’ said Napier-Bell. ‘I thought it was too difficult and the only person I really liked in the group – apart from Chris Dreja, who is a nice guy, a good person – was Jeff Beck. So I kept the management of Jeff Beck. I found Jimmy very difficult to deal with. Always narky.’

Page, however, felt it was unsurprising he was considered awkward: ‘Bloody right. We did four weeks with the Rolling Stones and then an American tour and all we got was £112 each!’

One aspect of Page that Napier-Bell had observed was the guitarist’s tendency to be tucked away in a corner reading yet another esoteric volume by Aleister Crowley. ‘People would ask him about it, and he would reply something along the lines of, “Oh, you wouldn’t understand it. You’re not intelligent enough.”’

6

‘YOU’RE GOING TO KILL ME FOR A THOUSAND DOLLARS?’

If Aleister Crowley performed a role as a kind of absent metaphysical father figure to Jimmy Page, the fastidiously loyal Peter Grant would prove to be a very physical manifestation of one.

Born into considerable poverty on 5 April 1935 in London’s South Norwood, Peter James Grant was the illegitimate son of a secretary. He never met his father, who was rumoured to have left his mother because she was Jewish – even though she was employed as a typist for the Church of England Pensions Board.

Soon Grant and his mother moved to a tiny terraced house in down-at-heel Battersea, on the edge of the Thames. During the Second World War his school was evacuated, and he was sent to Godalming in Surrey, where he was educated at posh public school Charterhouse. Bullied by resentful incumbents, he developed an abiding loathing of the upper classes that would remain with him all his life. Emotionally distraught at being torn from his mother and home, meagre though it was, Grant began to put on the excessive weight that would characterise him.

‘This boy will never make anything of his life,’ read the final report by the headmaster of the south London school where Grant finished his education.

The first few weeks of Peter Grant’s working life were spent labouring in a sheet-metal factory. At six feet, five inches tall and on his way to being just as wide, he certainly had the physique for physical work, but he quickly changed course, first becoming a messenger delivering photographs on Fleet Street for the Reuters news agency, and then a stagehand at the Croydon Empire Theatre.

After National Service in the Royal Army Ordnance Corps, where he attained the rank of corporal, he became doorman – bouncer, really – at the 2i’s Coffee Bar on Old Compton Street, the birthplace of British rock ’n’ roll and the venue from which sprang Cliff Richard, Tommy Steele and Adam Faith, among others. It was during this time that he met Mickie Most, who had recently returned to London after finding success as a pop star in his wife’s native South Africa.

Through connections he made with Most, Grant was swept up into the newly popular world of televised professional wrestling, appearing as both Count Massimo and Count Bruno Alassio of Milan. From this springboard Grant secured bit parts in a number of films – among them A Night to Remember, The Guns of Navarone and the epic Cleopatra – and television shows – The Saint, Dixon of Dock Green and The Benny Hill Show, among others.

Grant pulled together his 2i’s connections, bought a minibus and started a business transporting rock ’n’ roll musicians to their gigs. He started off with the Shadows, before he was approached by Don Arden, who gave Grant the task of road-managing American acts he brought over for tours – the Everly Brothers, Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, Little Richard, Gene Vincent and Brian Hyland – a role he performed with alacrity, personally ensuring the artists were paid every penny owed, in cash.

Arden had a very nasty reputation: he was rumoured to have held Steve Marriott, of the Small Faces, out of a third-floor office window by his ankles when the diminutive singer requested an accurate accounting of his earnings. Grant learned from such behaviour. ‘When he was with Led Zeppelin he was a batterer of people,’ said Napier-Bell. ‘Although that was probably because of the drugs. When he had cleaned up he became a very nice person.’

But that was all yet to come. Grant also acted as road manager for the Animals and the New Vaudeville Band, and began sharing an office with Mickie Most at 155 Oxford Street, on the border of then sleazy Soho in London. When Most took over the management of the Yardbirds from Napier-Bell, Grant became their de facto manager and Most’s partner in RAK Management.

‘They needed someone like Peter Grant,’ said Napier-Bell. ‘He wouldn’t stand for Jimmy Page’s sneering.’

The group was losing traction in the UK, but in America they still carried considerable cachet. Grant travelled with the band on the road in the US, and, for the first time, they returned to England with money in their pockets. ‘He was a great manager for the time,’ said Chris Dreja. ‘He was hands-on, nuts and bolts. He travelled with the band. He made sure they didn’t get screwed. He loved his artists. He changed the music scene. He was responsible, especially with Zeppelin, of course, because they had such a huge audience, for changing the percentage points around between the record companies and the artists and the promoters. He was just a fantastic manager.’

On a date in a snowbound northern American state, the bad weather caused the Yardbirds to arrive late, almost missing their call time. Furious at being so put out, the pair of Mafia promoters refused to pay the group’s fee, one of them pulling a gun. Peter Grant walked his considerable girth up to the man: ‘What? You’re going to kill me for a thousand dollars? I don’t think so.’ He got the Yardbirds their money.

Grant became close to Page, who, he noted, seemed in control of himself and intelligent, far more businesslike than the other Yardbirds and apparently much older than his 22 years. In this odd-couple relationship, Grant expressed his ‘utter faith’ in the young but extremely seasoned guitarist. ‘It was funny how well Jimmy and Peter got on because Jimmy was a very softly spoken, gentle guy and Peter was from a very different background and education,’ said Napier-Bell. Among other things, the pair shared an interest in antiques, and they would go shopping for them together on tour.

‘“Peter, there’s only one problem with the band,”’ Grant had been told by Napier-Bell. ‘“There’s a guy there who’s a real smart arse, a real wise guy.” I said, “Who’s that?” He said, “Jimmy Page.” I was a bit puzzled. I thought, he must know I’ve known Jimmy since 1962/63. Apart from Neil Christian, when I was in business with Mickie Most, he did all the Herman’s Hermits and Donovan. So when I met Jimmy I said, “I hear you’re a bit of troublemaker and I should get rid of you. What have you been up to?” He said, “We did a four-week tour of the UK with the Stones and an American tour and we got £112 each.” And he was the only one who had the balls or savvy to say something. By then Mickie Most was recording them. Mickie Most is a pop producer, an excellent pop producer. And there was always a bit of friction there. The way I saw the band going, the way they wanted to carry on, was against the pop thing.’

Yet Mickie Most appeared unaware of the cultural wind of change. ‘The intention,’ he said, ‘was to try and resuscitate their pop career.’

In October 1967 Most insisted that a new Yardbirds 45 was released in the United States: ‘Ten Little Indians’, a song penned by Harry Nilsson and included on his second album Pandemonium Shadow Show. A truly dreadful record, it climbed no higher in the American charts than number 96, although Page had attempted to save the song, which featured a cloying brass section, by turning this into a feature after it had been subjected to what became known as ‘reverse echo’.

That ‘Ten Little Indians’ was only released in America was a testament to how out of touch Mickie Most had become. Both Page and Grant were well aware of the emerging new underground scene in America, the more reflective, less materialistic outlook of the hippie audiences at Bill Graham’s Fillmore West auditorium in San Francisco, which became almost a temple to the Yardbirds. The soundtrack to this counter-culture was provided by the advent of FM radio and its new ‘progressive rock’ stations like San Francisco’s KSAN, New York’s WNEW and Orlando’s WORJ, which were prepared to play an entire album with no commentary from a DJ (in the UK this was mirrored to an extent by John Peel’s late-night The Perfumed Garden show on the pirate-ship Radio London).

The ‘Season of the Witch’ was upon us. There was a new generation of American music-makers with very strange, surreal and hitherto unimaginable names that suggested copious drug consumption: Strawberry Alarm Clock, Captain Beefheart, Love, the Doors, Iron Butterfly, Jefferson Airplane, Moby Grape, Quicksilver Messenger Service, the Grateful Dead. They were all allied to the burgeoning ‘rock’ album audience, a development spurred by the arrival in late 1965 of the first relatively cheap stereo systems. Long-haired, free-loving, pot-smoking and acid-dropping, this new market was cemented together by the considerable schism in American society brought about by the ceaselessly expanding war in Vietnam. Crisscrossing the United States with the Yardbirds, Page and Grant witnessed the success of first Cream and then the Jimi Hendrix Experience, seeing how they fitted perfectly into this new world. It was a musical and cultural sea change.

Another of these novel new acts, the Velvet Underground, championed in New York City by the artist Andy Warhol, supported the Yardbirds on several shows in the winter of 1966, most notably a show at Michigan State Fairgrounds. Soon the Yardbirds started dropping a snatch of the Velvet Underground’s ‘I’m Waiting for the Man’, the group’s paean to heroin dealers, into the middle section of an extended version of their own tune ‘I’m a Man’. Page had heard the Velvets’ first album while touring the USA with the Yardbirds. ‘I’m pretty certain we were the first people to cover the Velvet Underground,’ he said. At one of those Manhattan parties at which Andy Warhol was ubiquitous, the artist asked the guitarist to take part in a screen test for him for a movie he had in mind.

As the sole guitarist with the now four-piece Yardbirds, Page spent much of 1967 and the first half of the next year on long, gruelling tours in far-flung places. It was relentless. There were five American tours, a UK tour, a European tour and in January 1967 an Australasian tour with Roy Orbison and the Walker Brothers, playing two shows a night. But it was not without its rewards. ‘When Jeff left and we carried on,’ he said, ‘the pure nature of the band was that they had a lot of numbers you could really stretch out on.’

Back in Britain from Australia during February 1967, Page worked with Brian Jones at IBC Studios on the soundtrack for A Degree of Murder. Directed by German New Wave filmmaker Volker Schlöndorff and starring Jones’s girlfriend Anita Pallenberg, the film was entered for competition at the 1967 Cannes Film Festival. Although both Page and Nicky Hopkins, the celebrated session pianist, played on the soundtrack, along with Small Faces drummer Kenney Jones, with Glyn Johns engineering, there was never an official release for Brian Jones’s music. ‘Brian knew what he was doing,’ said Page to Rolling Stone. ‘It was quite beautiful. Some of it was made up at the time; some of it was stuff I was augmenting with him. I was definitely playing with the violin bow. Brian had this guitar that had a volume pedal – he could get gunshots with it. There was a Mellotron there. He was moving forward with ideas.’