Полная версия

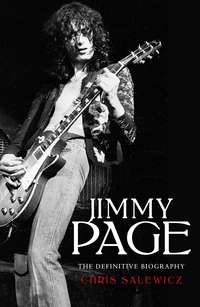

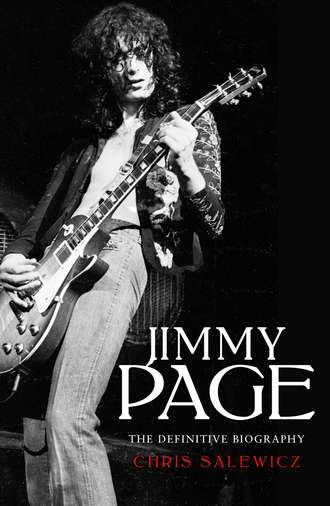

Jimmy Page: The Definitive Biography

‘I was travelling around all the time in a bus,’ he told Cameron Crowe in Rolling Stone in 1975. ‘I did that for two years after I left school, to the point where I was starting to get really good bread. But I was getting ill. So I went back to art college. And that was a total change in direction … As dedicated as I was to playing the guitar, I knew doing it that way was doing me in forever. Every two months I had glandular fever. So for the next eighteen months I was living on ten dollars a week and getting my strength up. But I was still playing.’

Only days after Jimmy Page left Neil Christian and the Crusaders he experienced something of an epiphany. For the very first time a package tour of American blues artists was scheduled to play in the United Kingdom. Following concerts in Germany, Switzerland, Austria and France, the American Folk Blues Festival had a date scheduled on 22 October 1962 at Manchester’s Free Trade Hall, with both afternoon and evening performances. On the bill were Memphis Slim, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Helen Humes, Shakey Jake Harris, T-Bone Walker and John Lee Hooker.

Page arranged to go with his friend David Williams, but opted to catch the train and meet him in Manchester rather than travel together by road. By now he seemed to have registered that one of the causes of his ill health had been squeezing into an uncomfortable van to travel those long distances across Britain with the Crusaders.

David Williams travelled with a trio of companions he had met at Alexis Korner’s Ealing Jazz Club, in reality no more than a room in a basement off Ealing Broadway in West London. Fellow aficionados of this music, these companions had recently formed a group. Its name? The Rolling Stones. These new friends were called Mick Jagger, Keith Richards and Brian Jones.

Although the first set of the American Folk Blues Festival rather failed to fire, perhaps an expression of the wet Manchester afternoon that it was, the evening house more than lived up to their expectations. Especially when John Lee Hooker closed the show with a brief, three-song set, accompanied only by his guitar. ‘It may have been a damp and grey Manchester outside, but we thought we were sweltering down on the Delta,’ said Williams. Hooker had been preceded by T-Bone Walker, the ‘absolute personification of cool’, according to Williams. ‘He performed his famous “Stormy Monday” on his light-coloured Gibson. His playing seemed effortless, and his set just got better and better as he dropped the guitar between his legs and then swung it up behind his head for a solo. I did not look at Jim, Keith or any of the others while this was all going on, but I can tell you that afterwards they were full of praise and mightily impressed.’

Page, Jagger, Richards, Jones and Williams then drove back to London through the night, Jones nervous about the rate of knots at which they were travelling. In 1962 the M1, Britain’s only motorway, extended no further from London than to the outskirts of Birmingham, a hundred miles north of the capital. ‘Eventually we made it to the motorway and came across an all-night service station. Again, for most of us this was a real novelty. However, Jim was a seasoned night-traveller by now and he clearly enjoyed talking me through the delights of the fry-up menu. After a feed we resumed our journey, and it was still dark when we reached the outskirts of London.’

Early on in his time at Sutton Art College, Page encountered a fellow student called Annetta Beck. Annetta had a younger brother called Jeff, who had recently quit his own course at Wimbledon Art College for a job spray-painting cars. Hot-rod-type motors would become an obsession for Beck.

In a 1985 radio interview on California’s KMET, Beck told host Cynthia Foxx: ‘My older sister, as I remember it, came home raving about this guy who played electric guitar. I mean she was always the first to say, “Shut that racket up! Stop playing that horrible noise!” And then when she went to art school the whole thing changed. The recognition of somebody else doing the same thing must have changed her mind. She comes home screaming back into the house saying, “I know a guy who does what you do.” And I was really interested because I thought I was the only mad person around. But she told me where this guy lived and said that it was okay to go around and visit. And to see someone else with these strange-looking electric guitars was great. And I went in there, into Jimmy’s front room … and he got his little acoustic guitar out and started playing away – it was great. He sang Buddy Holly songs. From then on we were just really close. His mum bought him a tape recorder and we used to make home recordings together. I think he sold them for a great sum of money to Immediate Records.’

Beck and Page began to spend afternoons and evenings at Page’s parents’ home, playing together and bouncing ideas off each other. Page would be playing a Gretsch Country Gentleman, running through songs like Ricky Nelson’s ‘My Babe’ and ‘It’s Late’, inspired by Nelson’s guitarist James Burton – ‘so great’, according to Beck. They would play back and listen to their jams on Page’s two-track tape recorder. The microphone would be smothered under one of the sofa’s cushions when they played. ‘I used to bash it, and it would make the best bass drum sound you ever heard!’ said Beck.

But this extra-curricular musical experimentation was not necessarily in opposition to what Page was doing on his art course at Sutton Art College: rather, these two aspects of himself complemented each other. Many years later, when asking Page about his career with Led Zeppelin, Brad Tolinski suggested that ‘the idea of having a grand vision and sticking to it is more characteristic of the fine arts than of rock music: did your having attended art school influence your thinking?’

‘No doubt about it,’ Page replied. ‘One thing I discovered was that most of the abstract painters that I admired were also very good technical draftsmen. Each had spent long periods of time being an apprentice and learning the fundamentals of classical composition and painting before they went off to do their own thing.

‘This made an impact on me because I could see I was running on a parallel path with my music. Playing in my early bands, working as a studio musician, producing and going to art school was, in retrospect, my apprenticeship. I was learning and creating a solid foundation of ideas, but I wasn’t really playing music. Then I joined the Yardbirds, and suddenly – bang! – all that I had learned began to fall into place, and I was off and ready to do something interesting. I had a voracious appetite for this new feeling of confidence.’

Despite starting his studies at Sutton, Page would, from time to time, step in during evening sessions with Cyril Davies’s and Alexis Korner’s R&B All-Stars at the Marquee Club and other London venues, such as Richmond’s Crawdaddy Club or at nearby Eel Pie Island. Soon he was offered a permanent gig as the guitarist with the R&B All-Stars, but he turned it down, worried that his illness might recur.

There was another guitar player on the scene at the time, a callow youth nicknamed Plimsolls, on account of his footwear. Although at first Plimsolls could hardly play at all, he was known to have a reasonably moneyed background that enabled him to own a new Kay guitar. He had another sobriquet, Eric the Mod, a reflection of his stylish dress sense, and he would shortly enjoy greater success when, rather like his idol Robert Johnson, he seemed to suddenly master his instrument, and he reverted to his full name: Eric Clapton.

Page recalled that one night after he had sat in with the R&B All-Stars, ‘Eric came up and said he’d seen some of the sets we’d done and told me, “You play like Matt Murphy,” Memphis Slim’s guitarist, and I said I really liked Matt Murphy and actually he was one of the ones that I’d followed quite heavily.’

Eric Clapton was not the only one to note Page’s expertise. Soon came an approach from John Gibb of the Silhouettes, a group from Mitcham, on the furthest extremes of south London. Gibb asked Page to help record some singles for EMI, starting off with a tune called ‘The Worryin’ Kind’.

The Silhouettes would later occasionally feature Page’s new friend Jeff Beck on guitar. What has always been a fascinating psychogeographical truth is that Jimmy Page, Eric Clapton and Jeff Beck, Britain’s greatest and most creative rock guitarists of the 1960s, grew up within a radius of about 12 miles of each other.

Having witnessed Page’s guitar skills with the R&B All-Stars at the Marquee Club, Mike Leander, a young arranger and producer, pulled him into a studio for a stint as rhythm guitarist in late 1962. Page was moonlighting from art school – something that would become a pattern.

Leander had been alerted to go and check out Page by Glyn Johns, another Epsom boy, a couple of years older than Page who had watched him play years before and was now a tape operator. Of that first meeting, years before, Johns said: ‘One evening we had a talent night. I remember a boy in his early teens no one had seen before, who sat with his legs swinging over the front edge of the stage and played an acoustic guitar. He was pretty good, he may have even won, but I don’t think anyone in the hall that night had any idea that he was to become such an innovative force in modern music.’

‘I was really surprised,’ Page told Beat Instrumental magazine in 1965 about Leander asking him to play. ‘Before that I thought session work was a “closed shop”.

‘Mike was an independent producer then. And he wanted me to play on “Your Momma’s Out of Town” by the Carter-Lewis group. The record was released and I believe it helped him considerably in joining Decca full time.’

Soon Mike Leander had another, more prestigious session gig for Page. This studio date was with Shadows expatriates Jet Harris, a bass player, and drummer Tony Meehan. The resulting tune, ‘Diamonds’, was a number one smash, the first of a run of hits for the duo. Later, Harris and Meehan hired one John Baldwin to accompany their act on the road. Already there were glimmers of some kind of destiny at work; soon John Baldwin would metamorphose into John Paul Jones, so renamed for a solo single by Rolling Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham; Baldwin’s new moniker was derived from the film John Paul Jones, a popular 1959 movie about the famed US naval commander.

Even though Harris and Meehan had departed the Shadows, it was a huge honour for the 18-year-old Page to play with the alumni of the group that, prior to the Beatles, was the biggest in the UK, largely due to the skill and charisma of Hank Marvin, their bespectacled guitarist.

‘When did I first discover Hank Marvin? When I was about 14, because in those days it was really skiffle for young kids who wanted to learn three chords and have a good time,’ Page told John Sugar on BBC Radio 4 in 2011. ‘But going past that, more into the world of the American rockabilly and rock ’n’ roll was starting to seduce us all as kids. Then you had Cliff Richard and the Drifters [as the Shadows were first known] at that time, putting forward a really, really damned good rendition of it, but it still had that sort of grit identity to it.

‘So really it was a question of seeing Hank playing with Cliff as a kid, looking at Hank on the television. He was good, but he came alive with the Shadows. I mean it was such a really, really good band and Hank was such a stylist … I mean, he was so cool. He was and still is. He had this image … He was such a fluent player … In those early years, all of us – Jeff Beck, myself, Eric Clapton – we all played things like “Apache”, “Man of Mystery”, “F.B.I.”, those sort of [Shadows] hits …

‘Hank managed to come up with this unique sound, and that sound is just so recognisable. He inspired so many guitarists in those days as kids, kids who had no idea they may even be rock stars themselves one day.’

Playing guitar with Jet Harris and Tony Meehan on live dates, along with John Baldwin, was one John McLaughlin, who had given Page some guitar lessons when McLaughlin was working in a guitar shop. ‘I would say he was the best jazz guitarist in England then, in the traditional mode of Johnny Smith and Tal Farlow,’ said Page. ‘He certainly taught me a lot about chord progressions and things like that. He was so fluent and so far ahead, way out there, and I learned a hell of a lot.’

The ‘Diamonds’ session kick-started a new career for Page, one in which he would play up to ten sessions a week, although he was still officially at Sutton Art College. For the next three and a half years, again while officially still a student, he became one of the UK’s top two guitar session players: the other was Big Jim Sullivan, and for a time the boy from Epsom, where he continued to live at his parents’ house, became known as ‘Little Jim’. Working with all manner of artists and styles, he honed his guitar playing during this period. In his early sessions he largely used a black Les Paul Custom he had played with Neil Christian. Known as ‘the fretless wonder’, and with a trio of pickups, it gave Page great tonal flexibility. When required, he also used a 1937 Cromwell archtop acoustic guitar and a Burns amplifier, or from time to time a Fender Telecaster.

In June 1963 Page was interviewed on Channel Television, ITV’s smallest franchise, broadcasting only to the 60,000 inhabitants of the Channel Islands. With his hair immaculately swept back, Page certainly looked the rocking part, yet his accent and precise, formal speech constructions suggested someone from a rather more middle-class background than his actually was. Noted for the duty-free alcohol and tobacco on offer in this UK tax haven, Jersey and Guernsey enjoyed a certain hip cachet as a holiday location: was that why Page was there?

The interview was filmed on an outdoor quayside. The first question was the set-up:

What is a session guitarist?

‘A guitarist who’s brought in to make records, not necessarily doing one-night stands, hoping they’ll get into the hit parade – only getting an ordinary fee.’

He doesn’t work for any particular singer all the time?

‘Not necessarily.’

I gather there are only a few young session guitarists like yourself: why is that?

‘Well, it seems to be quite a closed shop. The Musicians’ Union have their own chaps in and they don’t really like to get the young people in because the old boys need the work.’

So how did you become a session guitarist?

‘I don’t know. Perhaps it was because I had the feel for it.’

How long have you been playing the guitar?

‘Four years.’

Have you always been a session guitarist?

‘No, no. For the last 18 months.’

Do you play for a regular group yourself?

‘Yes: Neil Christian and the Crusaders.’ [By now Page was no longer playing with them.]

And what sort of things do you do with this group?

‘Well, we do one-night stands all over England.’

What are the big names that you have backed on disc?

‘Jet Harris and Tony Meehan, Eden Kane, Duffy Power.’

What is it like working with some of the really big names of show business?

‘Disappointing.’

Why is that?

‘Well, they don’t come up to how you expect them to be. Rather disappointing on the whole, I would say.’

That’s probably bad news for some record fans. What is your professional ambition? Do you want to be a guitarist all the time? Do you want to make your own records?

‘No, not necessarily. I’m very interested in art. I think I’d like to become an accomplished artist.’

Rather than a guitarist?

‘Yes, possibly.’

Is this a means to an end for you? Are you hoping to earn enough money through your guitar playing?

‘Yes. Yes. I’m hoping to finance my art by the guitar.’

The quality of the acts Page worked with built steadily. Carter-Lewis and the Southerners’ ‘Your Momma’s Out of Town’ was an early example. ‘He was a fast player, he knew his rock ’n’ roll and he added to that,’ said John Carter. ‘He was also quiet and a bit of an intellectual.’

John Carter and Ken Lewis were essentially songwriters, with a sub-career as backing singers: the first hit they wrote was ‘Will I What?’, the number eighteen follow-up to Mike Sarne’s 1962 novelty number one hit ‘Come Outside’. They had been persuaded to form Carter-Lewis and the Southerners to promote their material. As a session musician Page played guitar on ‘That’s What I Want’, a Carter-Lewis song that became a Top 40 hit in 1964 for the Marauders, a group from Stoke-on-Trent. Then Page briefly became an actual member of the group. Viv Prince, later drummer with the Pretty Things, played with the group while Page was with them, along with Big Jim Sullivan and drummer Bobby Graham. By 1964 Carter-Lewis and the Southerners would become the Ivy League and then magically transform into the Flower Pot Men, who in 1967 hit the UK number four slot with ‘Let’s Go to San Francisco’.

Page also played on records as diverse as ‘Walk Tall’ by Val Doonican, a kind of Irish Perry Como, and – on 6 November 1964 – with another Irish singer, Them vocalist Van Morrison, on the Belfast group’s ‘Baby, Please Don’t Go’, its B-side ‘Gloria’, and follow-up single ‘Here Comes the Night’.

The twin pillars of Them were Van Morrison and guitarist Billy Harrison. ‘We were brought over,’ said Harrison, ‘in the middle of 1964 and stuck in Decca’s West Hampstead studio to see what we had. We did “Baby, Please Don’t Go”, “Gloria” and “Don’t Stop Crying Now”, which was released as the first single and died a death.’

The sessions were produced by Bert Berns, a streetwise New Yorker who had become a songwriter and record producer of some significance; a crucial figure at Atlantic Records – he revived the career of the Drifters and brought Solomon Burke to the label – he would later run Atlantic’s BANG label, kickstarting the solo careers of Van Morrison and Neil Diamond. At first, influenced by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, the white songwriting team from Los Angeles who via their cartoon-like wit transformed the subject matter of rhythm and blues, Bert Berns had been a composer of considerable success, subtly lacing his tunes with hypnotic Latin influences, especially mambo. Installed in New York’s famous Brill Building, the endlessly and effortlessly enthusiastic Berns co-wrote the Isley Brothers’ ‘Twist and Shout’, Solomon Burke’s ‘Everybody Needs Somebody to Love’, The Exciters’ ‘Tell Him’, Them’s ‘Here Comes the Night’ and the McCoys’ ‘Hang On Sloopy’, among many others. (As befitted the sometimes sleazy, occasionally Mob-affiliated world of New York popular music, Bert Berns, who everyone found a fabulous human being, attractive and glamorous to those with a fondness for boho chic, was allegedly ‘connected’, and possibly even a ‘made man’. From his rarefied perspective he would have given Page interesting instruction about the US music business. At their first sessions Led Zeppelin recorded a song about him, ‘Baby Come On Home’, subtitled ‘Tribute to Bert Berns’, an exceptionally beautiful soul tune of precisely the type Berns would have produced for Atlantic, which was not released until 1993. In Page’s guitar playing on this 1968 recording you can hear his love for Bert Berns.)

It was Bert Berns’s writing of the song ‘Twist and Shout’ that had first brought him to London. Covered by the Beatles, with John Lennon’s extraordinary, searing performance taking the song to a show-stopping further level, ‘Twist and Shout’ closed Please Please Me, the Liverpool group’s first album, the number one LP in the UK for 30 weeks in 1963. Although the Beatles meant nothing in America at that time, Berns’s first royalty cheque for his song on the album was for $90,000. In October 1963 he came over to London to see what was going on, producing a handful of no-hoper acts.

Already working in the British capital was Shel Talmy. A Los Angeleno who had worked with Capitol Records, he had been hired as staff producer by Dick Rowe, the Decca head of A&R – the man who famously turned down the Beatles but redeemed himself somewhat by signing the Rolling Stones. Rowe now decided that Bert Berns might fit as producer with the Belfast act he had signed named Them.

‘Twist and Shout’ had been covered yet again, by Brian Poole and the Tremeloes, who turned it into a Top 10 UK hit for Decca Records. It was something of a revenge release, as the act had been signed by Dick Rowe in preference to the Beatles – Brian Poole and the Tremeloes were, after all, from Essex, which was far more geographically convenient for a Londoner like Rowe than Liverpool.

In London, where he and Talmy were the only American producers working, Bert Berns had secured work through Decca Records, taking on ‘Little Jimmy’ Page as his principal session guitarist, recognising his talent and befriending him. ‘With the new breed of British producers such as Mickie Most or Andrew Loog Oldham trying as hard as they could to make records that sounded American,’ wrote Berns’s biographer Joel Selvin, ‘Berns was the first American producer trying to make records that sounded British.’

The sessions with Them for Decca proved as much, the resulting recorded songs utterly unique in the resounding clarity of their sound. ‘Bert Berns was inveigled into producing the session,’ said Billy Harrison. ‘And he brought in Jimmy Page, and Bobby Graham on drums. There was much grumbling, mostly from me, because I felt we could play without these guys. Jimmy Page played the same riff as the bass, chugging along. I played the lead: I wrote the riff.

‘Bert Berns had arguments with us about the sound. I thought we were playing it okay: if someone brought in session men you took it as a bit of a sleight. I was very volatile in those days.

‘There were various rows. Jimmy Page didn’t really seem to want to talk to anybody. Just a stuck-up prick who thought he was better than the rest of the world. Sat there in silence. No conversation out of the guy. No response.’

Possibly Billy Harrison was misinterpreting the shyness that other musicians felt characterised the quiet Jimmy Page. And he may have been projecting his personal prejudices. ‘He seemed above everybody, above these Paddies. That was the days when guest houses would have a sign up: “No salesmen, no coloured, no Irish”. Page had that sort of sneering attitude, as though he was looking down on everybody. He’s a fabulous technician, but there’s nothing wrong with a bit of friendliness.’

‘Their lead vocalist, Van Morrison, was really hostile as he didn’t want session men on his recordings,’ said drummer Bobby Graham. ‘I remember the MD, Arthur Greenslade, telling him that we were only there to help. He calmed down but he didn’t like it.’

‘Whatever Morrison’s reservations, they worked well together, and Graham’s frenzied drumming at the end of “Gloria” is one of rock’s great moments,’ wrote Spencer Leigh in his Independent obituary of Graham.

And the opening guitar riff on ‘Baby Please Don’t Go’ is one of the defining moments of popular music in the sixties. This was all Billy Harrison’s own work. ‘What annoyed me later,’ he said, ‘was that you would start to see how it was being said that Jimmy Page had played a blinding solo on “Baby Please Don’t Go”. I got narked about that: he never said he did it, but he never denied it.’

‘For a long time,’ said Jackie McAuley, who joined Them the next year, ‘Jimmy Page got credit for Billy Harrison’s guitar part. But he’s owned up about it.’

Bert Berns also pulled Page in for ‘Shout’, a cover of the Isley Brothers’ classic that was the debut hit for Glasgow’s Lulu & The Luvvers. And he had him add his guitar parts to her version of ‘Here Comes the Night’, a majestic version that was released prior to Them’s effort, but spent only one week in the UK charts.

Shel Talmy, a former classmate of Phil Spector at Fairfax High School in Los Angeles, also loved Page’s playing, and the guitarist was equally taken with him: a studio innovator, Shel Talmy would play with separation and recording levels, techniques that Page would assiduously study.