Полная версия

In Search of Klingsor

“I follow you, Professor. War is like a game.”

“Have you read my little article on the topic, the one published in 1928?” Von Neumann inquired, narrowing his eyes.

“‘On the Theory of Games of Strategy,’” replied Bacon. “I’ve heard about it, but I haven’t read it yet.”

“Right,” the professor mused. “All right. Suppose, then, that the war between Churchill and Hitler is a game. I will add one other condition—something that in the real case isn’t necessarily true at all, but in any event—the players that intervene in the game do so rationally.”

“I think I understand,” ventured Bacon. “They will do whatever it takes to obtain the result they desire: victory.”

“Very good.” Von Neumann finally smiled. “I’m working on a theory right now together with my friend, the economist Oskar Morgenstein. The theory states that all rational games must possess a mathematic solution.”

“A strategy.”

“You’ve got it, Bacon. The best strategy for any game—or war—is the one that leads to the best possible result,” Von Neumann cleared his throat with a swig of whisky. “Now, to my understanding, all games fall into one of two categories: zero-sum games and everything else. A game can only be considered zero-sum if the competitors are fighting over a finite, fixed object and if one person necessarily loses what the other one wins. If I only have one pie, each slice that I obtain represents a loss for my rival.”

“And in the non-zero-sum games, the advantages earned by one player don’t necessarily represent a loss for the other,” Bacon pronounced, satisfied.

“Right. Therefore, our war between the Nazis and the British …”

“… is a zero-sum game.”

“Correct. Let’s use it as a working hypothesis. What is the current status of the war? Hitler controls half of Europe. England barely puts up a fight. The Russians are holding out, waiting to see what happens, chained to their nonaggression pact with the Germans. If this is what things look like, Bacon, you tell me: What will be Hitler’s next move?” Von Neumann asked excitedly, his chest heaving up and down like a water pump.

It was a tough question, and Bacon knew there was a catch to it. His response shouldn’t reflect his intuition, he reasoned, but rather the mathematic expectations of his interrogator.

“Hitler is going to want another piece of that pie.”

“That’s exactly what I was hoping to hear!” Von Neumann exclaimed. “We’ve said that to Roosevelt over and over again. Now: Which piece, specifically?”

There were two possibilities. Bacon didn’t even flinch.

“I think Hitler’s going to start with Russia.”

“Why?”

“Because it’s the weakest of all his potential enemies, and he can’t allow Stalin to continue building his war chest for much longer.”

“Perfect, Bacon. Now comes the hard part.” Von Neumann was enjoying the young man’s astonishment. “Let’s take a look at our position on this issue, that of the United States of America. Right now we’re not involved, so we can be more objective. Let’s try to decide, rationally, what our course of action should be.”

Bacon and Von Neumann sat talking for over half an hour. In the meantime, the maid busied herself placing the plates and tablecloths in their proper places in the dining room, next to the drawing room. After a while, Klara, the professor’s wife—his second wife, actually—called out to Von Neumann from the staircase, chastising him for being late for his own party. Von Neumann waved his hand dismissively and signaled to his companion to stay where he was. Although he felt a bit silly, Bacon was enjoying the conversation; its dry humor and fast-paced exchanges reminded him of those chess games with his father so many years before. Beneath the apparent simplicity of this intellectual challenge, Bacon had the feeling that he was actually waging a most unusual battle against the professor. This was the kind of conversation he could imagine taking place between two spies from enemy countries, or two lovers unsure of one another’s affections. Each move was an attempt to get ahead of the next one, and so on and so on, and both men had to perform two tasks at once: They each had to carefully guard their own strategies, and at the same time figure out the other’s plan of attack. The conversation itself was a kind of game.

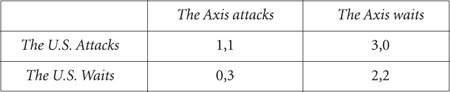

“My theory is the following,” said Von Neumann, as he took a sheet of paper from the coffee table and began outlining a neat, precise diagram. “The game we are playing with the Germans is not zero-sum because it involves the division of an even larger pie—the world—and there is a wide range of values ascribed to the different pie pieces that each side wants to keep for itself. This means that there are two strategies at play here, and four possible outcomes. The United States can decide to enter the war or not. The Axis countries can decide to attack us or not. What, then, are the four scenarios?”

Bacon responded with confidence:

“First, we attack them; second, they attack us by surprise; third, both sides attack simultaneously; fourth, things stay the way they are.”

“Now let’s consider the outcomes of each case. If we declare war, we have the potential advantage of surprising them, but many American lives would no doubt be lost in the process. If, on the other hand, they attack us first, they will possess that surprise margin but then they will be forced to wage a war on two fronts (provided that we are correct in assuming that they will attack the Reds at any time). Now, if we follow the third scenario and attack simultaneously, and go through all the obligatory declarations of war, etc., etc., both sides will have forfeited the surprise element, and both will suffer similar human losses. Now, if we opt for the last scenario, in which both sides leave things as they are, the likely outcome is that Hitler will take control of Europe and we will take North America, but in the long run, a conflict between the two sides will still be inevitable.”

“I like your analysis, Professor.”

“Thank you, Bacon. Now I’d like you to assign values to each of the possible outcomes, for our side and for theirs.”

“All right,” said Bacon, and he began to write on the piece of paper:

1. The United States and the Axis attack simultaneously: USA, 1; Axis, 1.

2. The United States launches a surprise attack against the Axis: USA, 3; Axis, 0.

3. The United States waits, and the Axis launches a surprise attack: USA, 0; Axis, 3.

4. The situation remains the same as it has been until now: USA, 2; Axis, 2.

Then Bacon drew the following diagram:

“The question is,” said Von Neumann, more excited than ever, “what should we do?”

Bacon contemplated the diagram as if it were a Renaissance painting. He found its simplicity as beautiful as Von Neumann did. It was a work of art.

“The worst-case scenario would be for us to wait and then get attacked by surprise. We would get a zero, and Adolf would come out with three. The problem is that we don’t know what that monster has planned. From that angle, I think the only rational solution is to attack first. If we can surprise the Nazis, then we earn a lovely three. If we simply engage in a simultaneous war, at least we’d get a one and not the zero that we’d deserve for being overly indulgent,” Bacon concluded, convinced. “That’s the answer. This way, at least, the outcome will depend on us.”

Von Neumann seemed even more satisfied than his student. Not only had Bacon proven his grit, but he and Von Neumann agreed about what decision President Roosevelt should make regarding the war. Ever since the discovery of uranium fission in 1939, Von Neumann had been one of the staunchest advocates for the establishment of a large-scale nuclear research program in the United States. An atomic bomb, if such a thing were possible, would not only take the Germans and the Japanese by surprise, but it could also end the war once and for all. Unfortunately, however, his message of warning had not seemed to have much effect on President Roosevelt.

“I think I shall have no other choice than to tolerate your tedious presence in the corridors of Fuld Hall,” Von Neumann announced, slowly rising from his chair. “But don’t go thinking this is paradise, Bacon. I am going to make you work like a mule until you end up despising every last equation I give you to solve. Be at my office next Monday.”

Von Neumann walked toward the staircase. The irritated voice of Klara Dan once again came bounding down from the second floor. Before retiring to his upstairs quarters, Von Neumann turned to Bacon one last time.

“If you don’t have anything better to do, you can stay for the party.”

In December of 1941, John von Neumann’s prediction came true, and the United States of America had no other choice but to enter the war. President Roosevelt had decided to remain neutral until the last possible moment, and the Japanese executed the best possible strategy: the surprise attack. The American public was shocked and outraged. Citizens from every walk of American life were angered and horrified.

HYPOTHESIS III: On Einstein and Love

By the time he had settled into his life in the United States, toward the end of 1933, Einstein was already something of an international genius, his mere image capable of inspiring even those unable to comprehend the slightest bit of physics. Having achieved this mythic status, the author of relativity amused himself by responding to his admirers’ innocent questions with riddles and paradoxes, brief as Buddhist parables. With his long, tangled mane of graying hair and his eyes, encircled by a frame of wrinkles, he was a hermit delivered to save the modern world, so desperately in need of his help. Journalists flocked to his home on Mercer Street seeking his opinion on every topic under the sun. A modern-day cross between Socrates and Confucius, Einstein obliged them with the serene benevolence of a teacher addressing the timid ignorance of his pupils. Stories of these press conferences quickly began to circulate from one end of the country to the other, as if every one of his answers were some kind of Zen koan, a Sufi poem, or a Talmudic aphorism. On one occasion, a reporter asked Einstein the following question:

“Is there such a thing as a formula for success in life?”

“Yes, there is.”

“What is it?” asked the reporter, impatient.

“If a represents success, I would say that the formula is a=x+y+z, in which x is work and y is luck,” explained Einstein.

“What is z, then?” questioned the reporter.

Einstein smiled, and then answered: “Keeping your mouth shut.”

These stories, brief and concise, only served to enhance his prestige, but at the same time, they fueled the ire of his enemies. In those days, the world was divided into two camps: those who adored Einstein and those who, like the Nazis, would have done anything to see him dead.

In 1931, when Einstein was in Pasadena to deliver a lecture at the California Institute of Technology, Abraham Flexner first approached him to join the Institute for Advanced Study, which was soon to be inaugurated at Princeton University. Flexner would make the same proposal to Einstein once again, when the two men found themselves at Oxford University in 1932.

“Professor Einstein,” he said as they walked through the gardens of Christ Church College, “it is not my intention to dare to offer you a position at our institute, but if you think about it and feel that it might meet your needs, we would be more than disposed to accommodate whatever requirements you might have.” Einstein replied that he would think about it, and in early 1933 the political climate in Germany forced him to accept the offer.

By the early 1930s, members of Hitler’s party were winning more and more seats in the Reichstag. In the 1932 elections, for example, more than two hundred Nazi deputies joined the ranks of the Reichstag, which was now under the control of the artful, cagey Hermann Goering. Around that time, Einstein and his second wife, Elsa, realized that sooner or later they would have to flee Germany. A third telephone call from Abraham Flexner, this time to Einstein’s home in Caputh, in the outskirts of Berlin, convinced the couple to cross the Atlantic. Taking advantage of the new season of conferences and lectures in the United States, Einstein promised Flexner that he would pay a visit to the institute, which would allow him to finally make a decision regarding the offer. Upon leaving their home, Einstein looked at his wife’s careworn face and in the admonishing tone he reserved for truly tragic moments, he said to her: “Dreh’ dich um. Du sieht’s nie wieder.” That is, “Don’t turn around. You’ll never see it again.” In January of 1933, Einstein was at the conference in Pasadena when Hitler was named chancellor of the Reich by President Von Hindenburg. In one interview, Einstein confirmed the prediction he had recently made to his wife: “I won’t be going home.”

Taking care not to go anywhere near Germany, Albert and Elsa returned to Europe, where Einstein still had several academic commitments to fulfill. Goering, in the meantime, wasted no time in denouncing the communist conspiracy behind “Jewish science” during one of his incendiary speeches in the Reichstag, disavowing Albert Einstein as well as his life’s work. Several Nazi assault units broke into the physicist’s home in Caputh, in search of the armaments that they were certain the communists had stored there.

Einstein then paid a brief visit to the Belgian coast, and upon ensuring that Flexner was indeed prepared to agree to his conditions—an annual salary of $15,000 and a position for one of his assistants—he accepted the appointment at Princeton. On the seventeenth of October 1933, he disembarked from the steamship Westmoreland on Quarantine Island, New York, and from there he took a motorboat that whisked him away, incognito, to the New Jersey shore and then straight to the Peacock Inn, in the town of Princeton.

The new institute seemed to have been created exclusively for Einstein. In Flexner’s own words, it was a haven that would allow scholars and scientists to work “without being carried off in the maelstrom of the immediate.” Contrary to the current trend at universities all over the world, the study of physics at the Institute for Advanced Study was to be purely theoretical; no classes at all would be offered. At the institute, Einstein would have no other obligation than to think. A new koan would come to epitomize his life in the United States. The same—or maybe it was another—reporter asked the wise man:

“Professor, you have developed theories that have changed the way we see the world, a giant step forward for science. So tell us, where is your laboratory?”

“Here,” replied Einstein, pointing to the fountain pen that peeked out from his jacket pocket.

Einstein had a method, a practice he resorted to frequently which enabled him to contemplate certain scientific issues that otherwise would have been impossible to envision. This technique was known as Gedankenexperiment, or “mental experiment,” and despite its contradictory-sounding name, it was common practice in the days of ancient Greece. All modern science, especially physics, was based upon the use of practical experiments to prove hypotheses. A theory was considered valid if and only if reality did not betray it, if its predictions could be fulfilled rigorously and without exception. Nevertheless, since the close of the previous century, very few pure physicists were amused by the idea of locking themselves in laboratories to battle against increasingly sophisticated machinery that, in the end, only proved things they already knew. The gulf between the theorists and the experimental physicists grew wider and wider, fiercer even than the rift between mathematicians and engineers. Due to this mutual animosity, the two camps only made contact when the circumstances absolutely required it. Though they were, in fact, mutually dependent, they did all they could to avoid one another, inventing the most far-fetched excuses to get out of attending one another’s seminars and conferences.

One of the most important—and controversial—of Einstein’s mental experiments was the EPR Paradox of 1935, which took its name from the initials of the three scientists who worked together on the experiment: Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky, and Nathan Rosen. Based entirely on a mental experiment (since the instruments to prove it didn’t exist), the EPR Paradox was an attempt to refute, once again, the quantum physics that so irked Einstein—the same quantum physics he himself had helped bring about. As defended by the Danish physicist Niels Bohr in the so-called Copenhagen Interpretation, quantum mechanics posited, among other things, the notion that chance was no accident at all, but rather a perfectly integral feature of the laws of physics. Einstein, of course, could not accept this idea. “God does not play dice with the universe,” he said to the physicist Max Born, and the EPR Paradox was a way of demonstrating certain aspects of quantum mechanics that he felt were scientifically unacceptable. Bohr and his followers, in turn, insinuated that Einstein had lost his mind.

Bacon belonged, as did Einstein, to the theoretical camp. Ever since the awakening of his youthful passion for theoretical mathematics, he had done everything possible to distance himself from concrete problems, focusing instead on formulas and equations that were increasingly more abstract, and in most cases exceedingly difficult to explain in real-world terms. Rather than struggle with particle accelerators and spectroscopic methods, Bacon chose instead to hide himself away in the far more pleasant realm of the imagination. There, he never ran the risk of dirtying his hands with things like radioactive waste, or exposing himself to dangerous X rays. To carry out his research, all that was required of him were perseverance and ingenuity. It was an approach to physics that, in a way, was a lot like chess.

Princeton, despite being one of the country’s great centers of academia, was an insipid place: too small, too American, too clean-cut, and too hypocritical. And contrary to the supposed “university tradition,” or perhaps because of it, a kind of stiff formality, a sameness, an uncomfortable kind of morality seemed to infect all the relationships one might cultivate there. The university itself was known for having a history of racism and anti-Semitism. To make matters worse, people felt even less able to express any kind of natural, day-to-day happiness, what with the war raging in Europe.

In order to escape these inconveniences, Bacon convinced himself very early on that the one area in which the theoretical world was useless and perhaps even perverse was sex. Theory, when you came down to it, was just fantasy. The tragedy was that almost nobody in the town of Princeton seemed able or willing to accept this basic idea—not the dean, the ministers, the mayor, the professors’ wives, the policemen, the doctors, not even the students themselves. No, they all insisted on performing endless mental experiments on the topic, and in the most unthinkable of places: in church, in lecture halls, in the eating clubs, at family gatherings, while taking their children to nursery school, as they walked their little dogs at sunset. And just like the men at the Institute for Advanced Study, the opaline community of Princeton limited itself to thinking about the pleasures no one dared consummate. For this very reason, Bacon detested his neighbors; they were insincere, provincial, and prudish. In this matter, Bacon could not be pacified with abstraction and fantasy: no intellect—not even that of Einstein—could come close to revealing the abundant diversity of life that was the female gender. Rational thought was fine for articulating laws and theories, for formulating hypotheses and corollaries, but it could never capture the infinite array of aromas, sensations, and pure intoxication swept together in a moment of passion. In other words: Because he was utterly incapable of relating to women of his own social class, Bacon had decided to invest his money in the world’s oldest profession.

In a moment of weakness, he met Vivien. He rarely spoke with her. It wasn’t that he didn’t care about her life or what she had to say—there were lots of women he cared little about yet tolerated long conversations with them. He just wanted to hold on to the idea that there was something mysterious and terrible about this woman. Her eyes, framed by a little halo that shone like a moon in eclipse, had to be hiding some kind of ancient secret, or maybe an accident or a crime, that could explain her evasive nature. Perhaps it wasn’t that at all—he never dared to ask—but he liked holding on to that illusion of living with a difficult soul; he treasured the trepidation he felt whenever he was in her presence. He envisioned Vivien, and with her he felt he could lose himself in a new, unknown land.

This was the closest he had ever come to love. Despite the passion he felt for her, however, Bacon took great pains to ensure that nobody ever caught sight of him walking through the streets of Princeton with Vivien. He always insisted on seeing her at his house, where she arrived with a ritual precision, as if offering up some kind of weekly sacrifice to the gods. Bacon, with the childish pleasure of committing a sin, of breaking an ironclad law, found himself in an emotional state the likes of which he had never known. He threw himself into proving this theory on Vivien between the sheets of his bed, with the tenacity that is the pride of the experimental physicist. Vivien, on the other hand, allowed herself to be manipulated with a serenity bordering on indolence; she had worked at a newsstand for a long time and, given all the alarming news she read daily, nothing could shock her. Vivien’s lovemaking was languorous and sweaty, like dancing to the blues. Her temperament reminded Bacon of that of a quiet little guinea pig or those calm, lazy caterpillars nestled in their moth-eaten leaves, indifferent to their predators lurking above.

As soon as she was finished undressing, Bacon would place Vivien facedown on the bed on the crisp, white sheets and turn on all the lights so he could study that optical antithesis, unbothered, for several minutes. When he was done, he would rest his body on top of hers and cover her with kisses. Every step of the way his lips tested the perfection of those beautiful little spherical equations that he knew he could never resolve. When he was through, he would turn her over as if she were a rag doll, and only then did he undress. Carefully he would separate Vivien’s thighs, and he would then nestle his face in the warm, welcoming space between her legs. This prelude was a kind of axiom from which several theorems emerged each time they came together, and this was where his analytic prowess was evident: this prelude, or groundwork, occasionally led him to Vivien’s tiny feet and, other times, to her nipples, her eyelashes, her belly button. It was more than mere lust: Bacon was studying sex in all its different incarnations, and was observing his own pleasure as it grew and evolved. In the end, the orgasm was just the logical, necessary consequence of the calculations he had mapped out earlier.

“I think it’s time for you to go,” he said to her, once he had recovered.

Maybe he did truly love her, but he just couldn’t stand the idea of her staying in his bed for very long, or having to kiss her when it was all over. By then, the heat they had created and the droplets of sweat that dotted her skin like translucent eyes made him sick—a repulsion as strong as the ecstasy he had just experienced. Suddenly, inevitably, he would become acutely aware of the animal quality of it all, and he couldn’t help imagining them as a couple of pigs rolling around in their own filth. His theory proven, he allowed Vivien just enough time to put herself back together and then he would simply ask her to leave. With the same indifference that, in some way, he sensed in her as well, he would watch her gather up her clothes and dress in silence as if watching an inanimate object or a doll. Once he was finally alone, Bacon felt nothing but sadness, quod erat demonstrandum, and usually fell into a dreamless slumber.