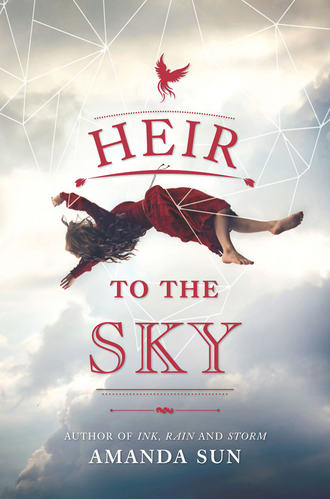

Полная версия

Heir To The Sky

“I would advise against it,” he tells me. “The Monarch has so much on his plate. I can assure you whatever the issue is, my father and the Elite Guard in Burumu can handle it.”

His advice annoys me. It’s like a patronizing pat on the head. “That’s the thing,” I say, before I can stop myself. “If this was a serious matter, you’d think the Sargon would’ve spoken up by now. Surely he doesn’t allow rebellion to take over Burumu?”

Jonash presses his lips together, likely to stop whatever words are dying to flow out. “Are you saying you have no confidence in my father, nor in me?” he says.

The question snaps me back into diplomacy. This is my fiancé, and I’m speaking without any tact at all. I don’t really care what he thinks of me, as I quietly seethe at him not taking me seriously. But I love my father, and I’m risking too much fanning flames between our families.

“Not at all,” I say, and I’m sure my face is flashing my irritation. “But something isn’t right about all this, and I won’t stop until I understand what it is. And that begins with informing my own father, who should know all rumors floating about the length of the sky.”

Jonash nods, but his eyes seem dim and distracted. “I see,” he says, but his tone disagrees. I assume he’s embarrassed, that whatever this rebellion is, it’s gone beyond the reach of his father, the Sargon, to deal with it. It’s a losing situation for him—if he doesn’t know of the rebellion, then he’s incompetent, and if he knows but can’t handle it, then he’s equally ill-equipped. Neither bodes well for an heir like him.

But the thought is mean-spirited. I didn’t know about the rebellion, either. Perhaps it’s new information that the lieutenant will share on their return. “I... I’m sure you will be able to address it when you return,” I offer.

“Indeed,” he says, and his eyes still look sunken in his face, but at least the anger has faded from his voice.

The path is dark now, the shining crystal of the citadel far behind us. Elisha reaches into her bag and pulls out a cast-iron lantern, carved all over with the shapes of stars and feathers for the light of the candle to dance through. We stop so she can strike the flint and light it, and she passes the lantern to me as well as the flint, which I slip into my pocket.

“Are we really going to go all the way to the outlands?” she says, and the candlelight flickers across her worried face. “I was only joking about the outcrop, you know. The sun’s set too quickly.” She looks around, and I know she fears the animals in the forests around us. We don’t have many predators on the continent, and they’re no bigger than deer—dwarf bears and wild boars mostly—but they’re protected by law in case we’re ever in desperate need to hunt for meat in years of drought or famine. There have been sightings of small dragons before, lighting up Lake Agur with fiery breaths, but they turned out to be a combination of lizards, fireflies and children’s wild imaginations. Monsters have never flown this high, but Elisha still fears the darkness. I’m sure our discussion of rebellion isn’t helping.

“We can turn back if you want,” I say. “And go tomorrow, in the light.”

“I was hoping to see the fireflies,” Jonash says, crestfallen. “I’ve heard they flash in every color in Ashra.”

“You two go ahead, then,” Elisha says, and I shoot her a warning look in the lantern light. You’re going to send me alone with him?

She arches her eyebrows in protest. He’s the son of the Sargon, she’s thinking. He’s a gentleman. But neither of us knows him, not really. I doubt he’d hurt me or force anything on me, for that would certainly break off the engagement and cause a terrible feud between our families and our continents. No, I’m much more afraid he’ll try to win me over, or that he’ll lean in for a kiss and I’ll lean away and everything will become terribly awkward.

“Let’s all go on, then,” Elisha says after a moment. “But only for a quick look, and we’ll head straight back.”

“Agreed,” I say. “It’s only about ten minutes to the clearing anyway.”

We walk the rest of the forest path in silence, listening to the wind rustling the leaves. I wish I’d brought my cloak. The nighttime air is always freezing in the sky.

The trees pull away then, and the outlands are before us. The tall grasses bend in the wind, rustling with the sound of the cold breeze. Fireflies thread through them like garlands of candlelight, flashing green and yellow and orange. I hold the lantern behind us to let our eyes adjust, and then the pink and purple and blue fireflies lift up, hovering above the grasses in wreaths of color.

Jonash steps forward, watching their colors flash. They go dim in front of him, blacking out along his entire path in their fear. But a moment later they light behind him, surrounding him in distant light.

“Go on,” Elisha whispers, nudging me forward. I wish she’d stop pushing me. But seeing Jonash in the field surrounded by those lights, seeing him appreciate the beauty of Ashra, makes me realize there’s so much about him I don’t know yet. Maybe this is an opportunity. He listened to my concerns about the strange extra tome that Aban and the lieutenant whispered over, even if he was a little patronizing. He didn’t take offense to what I said in the village. Elisha’s right that I do owe him more of a chance.

The grass scrapes against the sides of my ankles and the gaps between my sandal straps. The edges of the blades are sticky with sap and dry from too much sun. Dimmed fireflies accidentally bump into my arms and legs as I walk, and the lantern swings patterns of stars and feathers around the grasses. The fireflies darken in swarms around me, like snuffed-out candles.

“It’s wonderful,” Jonash says as I reach his side. “We only have yellow and orange fireflies in Burumu.”

“Most villagers in Ulan don’t come out as far as the outlands,” I say. “The edge of the continent is uneven here and difficult to see in the fields.” He looks alarmed, so I raise my hands to reassure him, the lantern swinging back and forth. “It’s out that way,” I say. “You can see it easily if you look for the moons hitting the rock.”

He peers over, so I take him closer to the edge to look. To me it’s like a lighting strip, silver and shiny as it loops along the side of the clearing. The two moons in the sky, one a crescent and one waxing full, beam down on the sparkling crystal fragments embedded in the stone of the continent’s edge. It’s like a glittering warning sign curving along the outlands. “See? Easy to spot once you know what to look for,” I tell him.

He crouches down to look at the sparkling stone. “I see it. It’s like a thread of glistening silver.”

I turn away, swinging the lantern at my side. The fireflies scatter from its light. “We should go back soon. Elisha will get spooked if we wait too long.”

“Of course,” he says, straightening up. “Only a little longer, and then I’ll escort you both, I promise.”

I roll my eyes, glad he can’t see my face. I don’t need his escort. I know every stone of Ashra, every curve of rock and packed earth. Nothing can harm me here. Only the wild animals need be avoided.

He follows a flashing blue firefly then, dangerously close to the edge. I wonder why he continues to veer so close now that he knows how to look for the silvery lip of the continent. Perhaps he’s fearless like me. Or perhaps he’s just foolish.

Now it’s as if he’s walking along a thin rope. My heart is fluttering. It wouldn’t do for my fiancé to drop off the side of the world. The Sargon wouldn’t be pleased, and neither would my father. “You’re too close, Jonash.”

He doesn’t answer, but stretches his arms out to the side to help balance. The fireflies shy away in clouds of twinkling light.

I take a step forward. “Jonash,” I try again. “Come away from the edge. The sheer crystal is slippery.” I take another step. “I’m sure it’s different on Burumu, but here...”

I don’t have a chance to finish my sentence. He begins toppling from side to side, and the horror claws at my insides. Before I realize it I’m leaping forward, throwing my arms around his waist to pull him into the tall grasses. He whirls around from the impact, the weight of him unbalancing my own footing.

I feel the scrape of the sharp crystals as they dig into my ankle, as my foot slips over the edge of the continent.

There’s no time to scream or think. My balance is off, and I’m falling backward, away from Jonash’s grim face. The lantern jangles against the cliff as it drops from my hand and tumbles sideways over the edge. Jonash’s hands on are my wrists, pulling them from his sides before we both go over. He falls stomach-down onto the grasses as my other foot slips over the side, shards of rock and dirt scraping the insides of my arms as I cling to the continent.

The cold wind gusts against me as I hang on. My feet swing and flail, but there’s nothing but air around them. The world is dark except for the glowing fireflies and the silver strip of crystal rock.

My wrists are slipping from Jonash’s fingers. I can barely breathe. “I can’t...”

“Kali, hang on,” he says. “Elisha! Help!” His shouts send the fireflies whirling in clouds.

I can hear Elisha yelling something, but my pulse is racing in my ears and I can’t make out a thing.

Jonash’s hands slide up my wrists, and he curls my fingers into the grasses and the thin layer of earth that clings to the bedrock. I grasp at them, but the grasses come up in handfuls. Is he that much of an idiot to think they’ll help keep me from falling? “Pull me up!” I scream at him.

The coolness of his fingers is gone, and the grass slips away. The edge of crystal rock scrapes the skin from the palms of my hands as I fall off the edge of the world.

I can hear screams, but I can’t tell if they’re mine. My body tumbles through the air, spinning over and over until I don’t know anything but cold gusts of black wind. The moons blink their stark white faces in a blur of light that tumbles over itself until I’m completely dizzy. The rainbow lights of the fireflies stretch away like stars until I see nothing but blackness.

I’m going to die. I’m going to hit the earth and the impact will kill me.

I can’t see in the darkness as I tumble round and round. I don’t know when I’ll hit, but it’s coming. I can’t tell if I’ve been falling for minutes or hours. The skirts of my dress are tangled around my legs. The wind whistles in my ears until I can’t hear or feel anything else.

I start to slow then, and the world stops tumbling. Have I died? They say when you die, the Phoenix burns a hole in the world and clasps you gently in her talons to take you away. But there’s no fire here, only cold air and a strange humming noise. And then a pale light spreads around me.

I look at my hand, drenched in a faint kaleidoscope of colors. It’s almost invisible, like when I catch a glimpse of rainbow light dancing on my hand from the ripples of Lake Agur. I’ve slowed so much it’s like floating in honey, the air thick and sluggish around me. I’m still falling, but drifting like a feather, buoyed gently down like I’m sinking into the lake.

And then there’s a strange sucking sound, and the rainbow lights waft from my fingers. I’m falling at full speed again, my back to the earth and my eyes cast upward. I look up at the two moons as they beam, unyieldingly bright in the sea of darkness.

I hear a great crash as if I’m in another world, and I feel a sharp pain everywhere at once. Then there is nothing but blackness and void.

SIX

THE FIRST THING I hear is the mournful sound of strange birds calling in the sky. They drone sour notes, followed by a long pause, and then more wails. I hear the stuttering of what might be a squirrel or some sort of pika. The air is thick and the breeze warm, like a flame tickling across my skin. I’ve never felt any wind like this before.

My eyes open slowly, the daylight overwhelming. My head throbs as I try to figure out where I am and what’s happened.

The fall. I’ve fallen off Ashra, down to the earth below. It seems impossible. I should be dead.

I rake my fingers against the ground and come up with sharp brown sapling needles. My eyes have trouble focusing on them even though my hand isn’t far away. My body feels like stone, every muscle crying out as I roll slowly onto my side.

Elisha, I think. Jonash. I remember the feel of the grass as it slipped from beneath my fingers. All those times I spent on the edge of my outcrop, never imagining I could fall.

I almost can’t believe it.

The branches of trees make a patchwork of sunlight that streams in from my left. Against my legs is a carpet of cold and damp. I squeeze my fingers and splay them. Moss, I realize. It’s thick moss I’ve landed on. I bend my knees and slide my legs against the fuzzy moist earth.

It isn’t anything like the rough drawings in the annals. It’s wild and beautiful, and so alive.

I take a deep breath, and wiggle my fingers. There’s a sharp pain when I turn my left wrist, and a pain in my chest when I breathe too deeply. But I’m alive, even if I’m injured.

I sit up slowly, my headache nearly knocking me down again. The spots in my eyes are clearing and the world is growing sharper.

I’ve landed in some sort of forest, though the trees are sparse and crooked. The whole floor of the woodland is covered in thick green-and-purple moss. Yellow-and-blue ferns unfurl in large floppy fans, and tiny sprigs of red flowers cluster like berries in the undergrowth.

The sour-sounding bird takes off with a rush of wings, his deep black feathers catching my eye as he soars past me. I look past him, up into the sky, to the looming dark island above. Ashra. It’s massive, even from so far away. Giant roots tangle through an upside-down pyramid of rich brown dirt that clings to the bottom of its rock bed. The edge of the continent is jagged and fractured from where Burumu and Nartu broke off. A mist of water pours like a thin cloud from the side of the continent, like a tiny tail of white that vanishes halfway down to the earth. The waterfall of Lake Agur.

The earth. I’m on the earth. My world, my friends, my father...they’re all high above on that floating continent, completely out of reach.

The thought jolts into me. The unrest in Burumu. The rebellion, the strange extra book and Aban’s key and his discussion with the lieutenant. My father has to know. How can I tell him now? Is he in danger?

I rub the side of my head with my right hand, the moss and tree needles matted in my hair. How long have I been out? A single night? A day or two? Do they know what’s happened to me? Elisha and Jonash would’ve gone for help right away. They’ll have the airships out looking by now.

But the airships have never flown this low. They’re bulky and unstable, difficult to maneuver. And finding me in this forest would be like finding a pika nest in the outlands, requiring more skill than the pilots have. They’re not even sure the ships would hold up to the difference in air pressure down here.

On top of that, it’s always been too risky to let the monsters know we’re still alive on the floating continents. Some of the beasts have wings and could be willing to fly up to devour what’s left of us.

My blood runs cold. The monsters. I’m like the unbelievers left behind in the illustration from the annals. It won’t take them long to find me. The annals said they can sniff out a human from miles away.

They’re probably already coming for me.

I rise to my feet in panic, but a deep, painful breath sends me tumbling down again. I cry out in agony and press my fingers against my ribs. My head twists to the side as I squeeze my eyes shut, tears stinging the corners. I’ve bruised my ribs, maybe broken them. I can’t outrun monsters like this.

I look around the sparse forest. I need some kind of shelter, some sort of safe place.

But there isn’t one. That’s why the Rending happened in the first place.

My heart thrums in my ears, the panic rising in my throat. Will the airships search for me? Will the people think a fall like that killed me? I shake my head. No—my father will look for me, I’m certain. He’ll hold out hope until the end. But he won’t find me in time. The earth is too vast. I wonder if I can even spot the airships from here. It doesn’t matter, because even if they could see me, they can’t retrieve me.

My every breath sounds earsplitting in the silence. No, I can’t give up. I’ve scaled rock bridges and swum closer to the waterfall of Ashra than any of the villagers in Ulan would dare. I’ve walked the edge of the outlands in the rainbow of fireflies hundreds of times before falling. One time, when Elisha and I were kids, we ran into a wild boar, and I chased it away with a stick while Elisha cried. I can do this. I won’t be defeated.

Safe places, I wonder. I could climb a tree. Can monsters climb? I’m sure some can, but anything’s better than sitting here on the ground like a pika on a platter.

I limp toward the nearest tree, resting my good wrist on the lowest branch. Hundreds of ants scurry up and down the splintered bark, but it’s no time to be squeamish. I press my sandaled foot against the trunk and wrap my other hand lightly around the branch. With a strong push I lift myself up. The pressure on my ribs and my left wrist make me cry out before I can stop myself, and I fall to the ground.

Tears of frustration burn in the corners of my eyes as I shake the ants off my fingers. I’ve climbed hundreds of trees on Ashra. Now, when my life depends on it, I’m helpless.

They’ll never find me in time, never find a way to reach me. But I can’t give up hope. I’m still alive, after all. I survived the fall.

I rise to my feet again, shaking the ants off the hem of my skirt. If I can’t climb the tree, then I need to find another way to hide myself. It’s been almost three hundred years. Maybe the monsters have all died away. Maybe they’ve forgotten about humans. Maybe there are still some sort of village ruins I can hide in until help comes.

If help comes.

I shake the thought away. There’s nothing to do right now but move forward. I walk along the edge of the trees, listening to the mournful songs of the birds, the rustling of the leaves. Surely if the monsters were near, the birds would stop singing, wouldn’t they? So as long as they sing, I’m safe.

I step past the wide leaves of the blue-and-yellow ferns and follow the line of trees toward the shadow cast by Ashra. The ground slopes down toward the gaping hole of missing land, where the floating island fit centuries ago. The land is jagged like the edges of a deep wound, sharp caverns and deep chasms. Nothing grows in the shadowlands, but on the edges, where the sunlight filters in, sprigs of hopeful trees and vines and weeds sprout in a desperate tangle.

It would be a good hiding place, but the road is steep down to the shadowed crater—climbing back up would be difficult. And the airships won’t see me underneath the continent. I imagine they’ll search the perimeter where I fell. Jonash will be able to show them the spot, so I shouldn’t stray too far.

I know they can’t reach me, but I cling to the hope anyway. It’s all I have.

I walk along the perimeter of the steep hillside for a while, listening carefully, watching my step, watching the skies. The Phoenix is with me, I think. She wouldn’t let her heir be extinguished. It’s a test and also maybe a blessing. I’ve always wanted to see the earth, and it’s every bit as wild and breathtaking as I’ve imagined.

The forest is full of insects I’ve never seen before, long iridescent bugs that beat two or three pairs of wings as they float from one strange plant to another. A tiny yellow lizard with a bright and glittering blue tail spreads out on the wide leaves of the ferns. And the breeze, that strange wind, carries warmth and heat in it. Surely it must be still warm from the flames of the Phoenix tossing Ashra and her lands sky bound. There’s no other explanation I can think of. The winds on Ashra are cold, but we’re closer to the sun, so the reason must be residual heat left from the Phoenix’s ashen sacrifice.

I walk along the perimeter of the forest for what seems like hours. There’s no end to the wild lands, no place I can find shelter or a clearing to wave at the airships if they come.

My stomach growls, and I tense at the sound. How long has it been since I’ve eaten? I think of the honeyed chicken and the puffed cakes at the festival. I reach into my pockets but only find the small piece of flint Elisha passed me with the lantern in the outlands.

I look around the sparse forest, wondering if there’s anything I can eat. The clusters of tiny red berries cling to the moss underfoot, and I wonder if they’re safe or poisonous. A bird calls out in the sky. Maybe I could take a fallen branch and whittle it with the flint to make a spear. But I’ve never had to hunt before. I’m not sure if I’d know how to lance a bird.

I bend down and wrap my fingers around a bunch of the berries, pulling it toward me until it plucks free from the brown stem. Each berry is barely the size of a tiny bead. I lift the bunch toward my nose and smell them. They’re pungent, a sickly smell like rotting. I squish one of the berries and the dark red juice runs down my hand like a trickle of blood.

I’m not sure what I’m looking for. I don’t know how to tell if they’re poisonous or not. But I’ll starve if I don’t eat anything. Surely one cluster wouldn’t kill me. And if I’m sick, then I’ll know for later.

I reach the berries toward my mouth and bite down on one. The tough skin punctures and sprays my tongue with bitter juice. I cough and sputter, spitting out the taste. The cluster drops and bounces gently against the moss while I wipe my mouth with the back of my hand. Not edible, then. Not even close.

My stomach claws against my insides, and my throat is parched. There has to be water somewhere nearby. The trees and moss and birds couldn’t survive without it, could they?

I trudge forward for what feels like another hour, the remnants of the bitter juice sticking to the insides of my cheeks. My tongue feels like a slab of stone, thick and dry in my mouth.

At last the trees thin, and there’s a small clearing of bright green tall grasses. The tops of them splay out like the grains we grow in Ulan. I peel the chaff away and pop the seeds I find into my mouth, crunching them desperately before swallowing them. They catch in my dry throat and I cough while my fingers unravel another seed from the grass. If only I’d grown up in the village like Elisha. Then I’d know if this was a crop of wheat or oats or barley, or anything at all that I could eat. My education was all about the Phoenix and how to govern with authority and grace. It was history and language and etiquette, which fork to use when. It seems ridiculous now, standing in this wild landscape. Which fork to use? Why not teach me which wild plants to eat, how to find water, how to identify crops? How far from reality have I been living?

I scrape at the tops of the prickly grass until my fingers bleed, swallowing down every seed I unwrap. They scratch my throat as they go down, and still my stomach growls as if I’ve eaten nothing at all.

The wind dips the grass, and I notice a small mound in the distance that doesn’t move with them. It’s just a little curve, a tuft of grass that doesn’t match the others. It’s pale yellow, sticking up just above view. I narrow my eyes and try to see more clearly.

Two dark black eyes stare back at me.

Every nerve in my body pulses. A beast. And it’s watching me.

My mind races. Is it a monster? An animal? It’s immovable, like a stone. I raise myself onto the balls of my feet to see its head better. Its yellow tufted hair fades to purple stripes on either side of its eyes. Its nostrils drip with condensed breath as it stares back at me. But that’s all I can see.