Полная версия

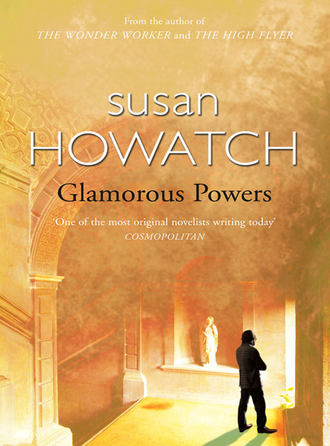

Glamorous Powers

Susan Howatch

GLAMOROUS POWERS

COPYRIGHT

HarperFiction An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 77–85 Fulham Palace Road, Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1988

Copyright © Leaftree Ltd 1988

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

SOURCE ISBN: 9780007396382

Ebook Edition © MAY 2012 ISBN: 9780007396382

Version: 2014-07-30

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

PART ONE:

THE VISION

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

PART TWO:

THE REALITY BEYOND THE VISION

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

PART THREE: THE FALSE LIGHT

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

PART FOUR: THE LIGHT FROM THE NORTH

ONE

TWO

AUTHOR’S NOTE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

PRAISE

BY SUSAN HOWATCH

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

PART ONE THE VISION

‘Ecstasy or vision begins when thought ceases, to our consciousness, to proceed from ourselves. It differs from dreaming, because the subject is awake. It differs from hallucinations, because there is no organic disturbance: it is, or claims to be, a temporary enhancement, not a partial disintegration, of the mental faculties. Lastly, it differs from poetical inspiration, because the imagination is passive. That perfectly sane people often experience such visions there is no manner of doubt.’

W. R. INGE

Dean of St Paul’s 1911–1934

Christian Mysticism

ONE

‘The apparent suddenness of the mystical revelation is quite normal; Plato in his undoubtedly genuine Seventh Letter speaks of the “leaping spark” by which divine inspiration flashes on him.’

W. R. INGE

Dean of St Paul’s 1911–1934

Mysticism in Religion

I

The vision began at a quarter to six; around me the room was suffused with light, not the pellucid light of a fine midsummer morning but the dim light of a wet dawn in May. I was sitting on the edge of my bed when without warning the gold lettering on the cover of the Bible began to glow.

I stood up as the bedside table deepened in hue, and the next moment the floorboards pulsed with light while in the corner the taps of the basin coruscated like silver in the sun. Backing around the edge of the bed I pressed my back against the wall before any further alteration of consciousness occurred. Firm contact with a solid object lessens the instinctive fear which must always accompany such a radical transcendence of time and space.

However after the initial fear comes the equally instinctive acceptance. I had closed my eyes to lessen the terror of disorientation but now I forced myself to open them. The cell was still glittering, but as I watched the glitter faded to a shimmer until the scene resembled a view seen through the wrong end of a telescope, and I could perceive my body, remote and abandoned, pressed against the wall by the bed as if impaled there by invisible nails. I looked aside – I could see my body turning its head – and immediately the darkness, moving from right to left, began to erase the telescopic view. My eyes closed, again warding off the fear of disorientation, and this time when I reopened them I found I was once more moving in a normal world.

I was myself, inhabiting my body as usual and walking along a path through a wood of beech trees. Insofar as I was conscious of any emotion I was aware of being at ease with my verdant tranquil surroundings, although I felt irritated by the persistent call of a wood-pigeon. However eventually the pigeon fell silent and as the path began to slope downhill I glanced to my left at the chapel in the dell below.

The chapel was small but exquisite in its classical symmetry; I was reminded of the work of Inigo Jones. In the dull green light of the surrounding woods the yellow stone glowed a dark gold, a voluptuous contrast to the grey medieval ruins which lay behind it. The ruins were in part hidden by ivy, but as I moved closer I could see the slits in the wall of the tower.

Reaching the floor of the dell I faced the chapel, now only fifty yards away across the sward, and it was then that I noticed the suitcase. Standing at the edge of the trees it was sprinkled with labels, the largest being a triangle of red, blue and black design; I was too far away to read the lettering. Afterwards I remembered that I had regarded this suitcase without either curiosity or surprise. Certainly I never slackened my pace as I headed for the chapel, and I believe I knew even then that the suitcase was a mere image on the retina of my mind, a symbol which at that point I had no interest in interpreting.

Hurrying up the steps of the porch I lifted the latch, pushed the righthand half of the double-doors wide open and paused to survey the interior beyond.

There was no transept. A central aisle stretched to the altar at the east end. The altar-table was stark in its austerity, the only adornment consisting of a plain wooden cross, but again I felt neither surprise nor curiosity. Evidently I was as accustomed to this sight as I was accustomed to the fact that the nave was only three-quarters full of pews. Walking across the empty space which separated the doors from the back pew I could smell the lilies which were blooming in a vase beneath the brass memorial plaque on my right. I gave them no more than a brief glance but when I looked back at the altar I saw that the light had changed.

The sun was penetrating the window which was set high in the wall to the left of the altar, and as the ray began to slant densely upon the cross I stopped dead. Unless I stood south of the Equator I was witnessing the impossible, for the sun could never shine from the north. I stared at the light until my eyes began to burn. Then sinking to my knees I covered my face with my hands, and as the vision at last dissolved, the knowledge was branded upon my mind that I had to abandon the work which suited me so well and begin my life anew in the world I had no wish to rejoin.

II

Opening my eyes I found myself back in my cell. I was no longer pressing against the wall but kneeling by the bed. Sweat prickled my forehead. My hands were trembling. There were also other physical manifestations which I prefer not to describe. Indeed I felt quite unfit to begin my daily work but so profound was my state of shock that I automatically embarked on my morning routine, and minutes later I was leaving my cell.

Perhaps I have erred in starting this narrative with an account of my vision. Perhaps I should instead have offered some essential biographical details, for the repeated mention of the word ‘cell’ has almost certainly conveyed the impression that I am an inmate of one of His Majesty’s prisons. Let me now correct this mistake. For the past seventeen years I have been a member of the Anglican brotherhood of monks known as the Fordite Order of St Benedict and St Bernard. I may still be judged eccentric, anti-social and possibly (after this account of my vision) deranged. But I am not a criminal.

In order that such an abnormal experience can be put in its proper context and judged fairly, I must attempt a thumbnail sketch of my past so let me state at once that in many ways my life has been exceedingly normal. I was brought up in a quiet respectable home, educated at various appropriate establishments and ordained as a clergyman of the Church of England not long after my twenty-third birthday. I then married a young woman who possessed what in my young day was described as ‘allure’ and which a later generation, debased by the War – the First War, as I suppose we must now call it – described as ‘It’. For some years after my marriage I worked as a chaplain to the Naval base at Starmouth, and later I volunteered for duty at sea with the result that much of my ministry was spent away from home. In fact I was absent when my wife died in 1912. For another seven years I continued my career in the Navy, but I judge it unnecessary to recount my war experiences. Suffice it to say that after the Battle of Jutland I never felt quite the same about the sea again.

Accordingly in 1919 I left the Navy and became the chaplain at Starmouth prison. The advantage of this change was that I was able to see more of my children, now adolescent, but the disadvantage was that I became aligned with an authority empowered to administer capital and corporal punishment, two practices which are entirely contrary to my conception of the Christian way to treat human beings. However I endured this harrowing ministry as best as I could until finally in 1923 the hour of my liberation dawned: with both my children launched on their adult lives I was able to retire to the Cambridgeshire village of Grantchester, where the Fordites had a house, and embark on my career as a monk. I had known the Abbot, James Reid, since my undergraduate days at the University two miles away, and although I had lost touch with him some years earlier it never occurred to me not to seek his help when I was at last free to join the Order.

I shall gloss over the disastrous beginning of my new life and simply state that after three months at Grantchester I was transferred to the Fordites’ farm at Ruydale, a remote corner of the North Yorkshire moors where the monks lived more in the austere style of Cistercians than Benedictines. Here I embarked on a successful cenobitic career which reached its apex in 1937 when I was transferred back to Grantchester to succeed James Reid as Abbot.

This brief autobiographical recital – remarkable more for what I have omitted than for what I have deigned to reveal – is all I intend to disclose at present about my past. No further disclosures are needed, I think, to show that my ministry has always demanded a strong constitution, absolute sanity and considerable reserves of spiritual strength. In short, although I write as a monk who has visions I am neither an hysteric nor a schizophrenic. I am a normal man with abnormal aspects – and having abnormal aspects, as Abbot James had assured me when I was a troubled young ordinand, was what being normal was all about.

‘But beware of those glamorous powers, Jon!’ he had urged after we had discussed my gifts as a psychic. ‘Beware of those powers which come from God but which can so easily be purloined by the Devil!’ This had proved a prophetic warning. For the next twenty years, while I remained in the world, my life was one long struggle to achieve the correct balance between the psychic and the spiritual so that I could develop properly as a priest, but it was a struggle I failed to win. There was little development. I did become a competent priest in the limited sense that the world judged my ministry to be effective, but my spiritual progress suffered from inadequate guidance and an undisciplined psyche. As Father Darcy told me later, I was like a brilliant child who had learnt the alphabet but had never been trained to read and write. However this situation changed when I became a monk, and it changed because for the first time I found the man who had the spiritual range and the sheer brute force of personality required to train me.

I have reached the subject of Father Darcy. Father Darcy is relevant to my vision because he made me the man I am today. I must describe him, but how does one describe a brilliant Christian monster? Father Darcy was unlike any other monk I have ever met. No doubt he was also unlike any monk St Benedict and St Bernard ever envisioned. Both intensely worldly and intensely spiritual (a rare and often bizarre combination) this modern cenobitic dictator was not only devout, gifted and wise but brutal, ruthless and power-mad.

As soon as he became the Abbot-General in 1910 he embarked on the task of waking up each of the four houses which had been slumbering on their comfortable endowments for decades. Having dusted down each monk he reorganized the finances and courted not only both Archbishops but the entire episcopal bench of the House of Lords in an effort to increase the Order’s worldly importance. As a private organization it was not directly connected to the Church of England, even though since its birth in the 1840s it had received the somewhat condescending blessings of successive Archbishops of Canterbury, but Father Darcy’s diplomatic ventures ensured that he and his abbots were treated with a new respect by the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Meanwhile the spiritual tone of the Order had been markedly raised, and by the time I became a monk in 1923 the Fordites were well known for the guidance and counselling given to those who sought their help. The restored tradition of Benedictine scholarship was also being noticed with approval.

It will be obvious from this description that Father Darcy had the charism of leadership but in fact he possessed all the major charisms and these gifts from God were buttressed and enhanced by a perfectly trained, immaculately disciplined psychic power which he had dedicated entirely to God’s service. He was a formidable priest, a formidable monk, a formidable man. But he was not likeable. However Father Darcy cared nothing for being liked. He would have considered such a desire petty and self-centred, indicative of a disturbed psyche which required a spiritual spring-cleaning. Father Darcy cared only about being respected by those outside the Order and obeyed by those within; such respect and obedience were necessary in order that he might work more efficiently for God, and Father Darcy, like all successful dictators, put a high value on efficiency.

My habit of calling him Father Darcy is new. Only people outside the Order call us monks by our surnames preceded by the title ‘Father’, if the monk be a priest, or ‘Brother’, if the monk be a layman. For the last thirty years Father Darcy had been addressed by his monks as ‘Father Abbot-General’ but after his death a month ago it had become necessary to adopt another designation in order to distinguish him from his successor, and to me ‘Father Cuthbert’ had merely conjured up a picture of a cosy old confessor unable to say boo to a goose. In accordance with the constitution of the Order which decreed that all monks were equal in death, he had been referred to throughout the burial service as ‘Cuthbert’ but whenever this word had been uttered something akin to a shudder of horror had rippled through the congregation as if Father Darcy were still alive to be enraged by the familiarity.

All the abbots attended the funeral. Cyril came from Starwater Abbey, where the Fordites ran a public school; Aidan, my former superior, came from Ruydale, and I came from Grantchester. Francis Ingram, Father Darcy’s right-hand man, organized the funeral and offered us all a lavish hospitality at the Order’s London headquarters, but he did not conduct the service. That task fell to Aidan as the senior surviving abbot.

‘It’s hard to believe the old boy’s gone,’ said Francis Ingram afterwards as he helped himself to a very large glass of port from the decanter which was normally reserved for visiting bishops. ‘What a wonderful capacity he had for making us all shit bricks! It’s going to be uncommonly dull without him.’

Monks are, of course, supposed to refrain from using coarse language but sometimes the effort of keeping one’s speech free of casual blasphemy is so intense that a lapse into vulgarity is seen as the only alternative to committing a sin. It is a notorious fact of monastic life that without the softening influence of women men tend to sink into coarse speech and even coarser humour; when I returned to Grantchester in 1937 as Abbot I found a community so lax that their conversation during the weekly recreation hour recalled not the cloister but the barracks of the Naval ratings at Starmouth.

My promotion in 1937 was unorthodox, not only because monks who follow the Benedictine Rule are supposed to remain in the same community for life but because the monks themselves normally elect an abbot from among their own number. However Father Darcy had decided I could be of more use to the Order at Grantchester than at Ruydale, and Father Darcy had no hesitation in riding rough-shod over tradition when the welfare of the Order was at stake.

‘Many congratulations!’ said Francis Ingram when I arrived at the London headquarters to be briefed for my new post. ‘I couldn’t be more pleased!’ Of course we both knew he was furious that I was to be an abbot while he remained a mere prior, but we both knew too that we had no choice but to go through the motions of displaying brotherly love. Monks are indeed supposed to regard all men with brotherly love, but since most monks are sinners not saints such exemplary Christian charity tends to resemble Utopia, a dream much admired but perpetually unattainable.

It was not until the April of 1940 when Father Darcy died that Francis and I saw our meticulously manifested brotherly love exposed as the fraud which it was. I have no intention of describing Father Darcy’s unedifying last hours in detail; such a description would be better confined to the pages – preferably the uncut pages – of a garish Victorian novel. Suffice it to say that for two days he knew he was dying and resolved to enjoy what little life remained to him by keeping us all on tenterhooks about the succession.

It is laid down in the constitution of the Order that although abbots are in normal circumstances to be elected, the Abbot-General must choose his own successor. The reasoning which lies behind this most undemocratic rule is that only the Abbot-General is in a position to judge which man might follow most ably in his footsteps, and the correct procedure is that his written choice should be committed to a sealed envelope which is only to be opened after his death. This move has the advantage of circumventing any last-minute dubious oral declarations and also, supposedly, removing from a dying Abbot-General any obligation to deal with worldly matters when his thoughts ought to be directed elsewhere. However Father Darcy could not bear to think he would be unable to witness our expressions when the appointment was announced, and eventually he succumbed to the temptation to embark on an illicit dénouement.

There were four of us present at his bedside, the three abbots and Francis Ingram.

‘Of course you’re all wondering how I’ve chosen my successor,’ said the old tyrant, revelling in his power, ‘so I’ll tell you: I’ve done it by process of elimination. You’re a good man, Aidan, but after so many years in a Yorkshire backwater you’d never survive in London. And you’re a good man too, Cyril – no one could run that school better than you – but the Order’s not a school and besides, like Aidan, you’re too old, too set in your ways.’

He paused to enjoy the emotions of his audience. Aidan was looking relieved; he would indeed have hated to leave Ruydale. Cyril was inscrutable but I was aware of his aura of desolation and I knew Father Darcy would be aware of it too. Meanwhile Francis was so white with tension that his face had assumed a greenish cast. That pleased Father Darcy. Aidan had been a disappointment, Cyril had been a pleasure and Francis had been a delight. That left me. Father Darcy looked at me and I looked at him and our minds locked. I tried to blot out his psychic invasion by silently reciting the Lord’s Prayer but when I broke down halfway through he smiled. He was a terrible old man but he did so enjoy being alive, and in the knowledge that his enjoyment could only be fleeting I resolved to be charitable; I smiled back.

Immediately he was furious. I was supposed to be writhing on the rack with Francis, not radiating charity, and as I sensed his anger I realized that in his extreme physical sickness his psychic control was slipping and his spiritual strength was severely impaired.

He said to me: ‘And now, I suppose, you’ve no doubt whatsoever that you’ll step into my shoes! Proud arrogant Jonathan – too proud to admit his burning curiosity about the succession and too arrogant to believe I could ever seriously consider another candidate for the post! But I did consider it. I considered Francis very seriously indeed.’ He sighed, his rheumy old eyes glittering with ecstasy as he recalled the next step in his process of elimination. ‘How hard it was to choose between the two of you!’ he whispered. ‘Francis has the first-class brain and the skill of the born administrator, but Jonathan has … well, we all know what Jonathan has, don’t we? Jonathan has the Powers – those Glamorous Powers, as poor old James used to call them – and they made Jonathan the most exciting novice I’ever encountered, so gifted yet so undisciplined, yes, you have all those gifts which Francis lacks, Jonathan, but it’s those gifts which make you vulnerable as you continue to wage your lifelong battle against your pride and your arrogance. Francis may be less gifted but that makes him less vulnerable, and besides,’ he added to Cyril and Aidan, ‘Francis has the breeding. Jonathan’s just the product of a schoolmaster’s mésalliance with a parlourmaid. He’d serve cheap port and young claret to all the important visitors, and that wouldn’t do, wouldn’t do at all – we must maintain the right style here, we’re a great Order, the greatest Order in the Church of England, and the Abbot-General must live in the manner of the Archbishop of Canterbury at Lambeth. So all things considered,’ said the old despot, battling on towards the climax of his dénouement, ‘and following the process of elimination to its inevitable conclusion, I really think that the next Abbot-General should be a man who can distinguish vintage claret from a French peasant’s “vin ordinaire”.’

He had lived long enough to see the expressions on our faces. Sinking blissfully into a coma he drifted on towards death until an hour later, to my rage and horror, the Abbot-General of the Fordite monks became none other than my enemy Francis Ingram.