Полная версия

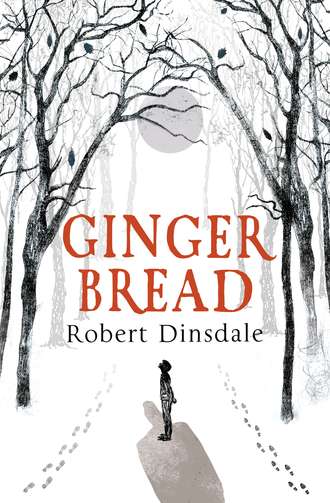

Gingerbread

Time slows down. The hands of the clock drag, each tick tolling with a tortuous lag.

There come three short raps, of hands knocking at the front door.

Yuri spins around, as if caught in some mischief. ‘But my stepfather isn’t home until the weekend!’

It is panic that seizes Yuri, as he endeavours to tidy the room, but the boy sits still and listens to Yuri’s mother crossing the flat to answer the door.

‘Come in,’ she says – and he hears, once again, the click of those jackboot heels.

After that, he knows what is coming. There is nowhere to run, and hiding would be useless. Yuri’s mother appears again in the doorway. She does not speak, but a soft look in her eyes compels the boy to stand and follow her, back through the flat, into the living room where the door stands open, with winter flurrying up in its frame.

There stands Grandfather. His white hair is emboldened by ice, and his whiskers carry their weight as well. In that frozen mask his eyes are piercing bolts of cobalt. He wears gloves through which bitten fingers show.

The boy goes to him, stalls, goes to him again, crossing the flat’s endless expanse in a stuttering dream. ‘Is she in hospital again?’ he says, with a tone that some might say is even hopeful.

Grandfather steps forward with clicking jackboots, crouches, and opens his greatcoat to put old and weathered arms around his grandson.

‘No, boy,’ he whispers with the sadness of mountains, of winters, of empty tenement flats. ‘No, boy, she won’t be going to hospital ever again.’

On the ledge by the window, its underbelly lit up by slivers of light shooting up through the floorboards: the little Russian horse that was a present from his mother.

It is cold in the tenement, and has been cold throughout the long, empty days. The boy counts them in his head: five, six, seven days since the jackboots clicked on the frigid metal stair, their steps tolling out the news. Now, with his eyes lingering on the little Russian horse, he waits for their clicking again. Today there has been nothing to do but wander up and down the hall, brooding on every photograph of the long ago, wondering at such things as soldiers and jackboots and guns.

When headlights roam the road outside, the Russian horse is trapped, monstrous, in the sweeping beams. The boy creeps up, as if he might peep over the ledge and look into the street below, but the creature leers at him and he is not brave enough to come near. He turns back, meaning to sit on his haunches in the corner of the room, but the horse’s shadow dominates the far wall. The boy starts, turns back to the tiny wooden toy just as the headlights pass on. Now, it is just a flaking Russian horse again, with its painted eyes and preposterous eyelashes, its ears erect like a fox, a twisted little creature he must always look after, no matter how malevolent it has become in the week since mama disappeared.

It is only when the headlights are dead that the boy goes to the window. On tiptoes he can heave himself up and look out onto the tenement yard. Mama’s car is parked at an awkward angle, one wheel up on the kerb. Ice still rimes the windscreen, so that the driver must have driven half-blind. Inside, a little heart of light glows.

When Grandfather appears, he is clutching a brown parcel to his breast. He takes off, but does not lock the car behind him. Soon, after he has crossed the tenement yard, he disappears from sight. The boy listens out for the click of his boots on the concrete. Then, he drops from the window ledge, upending the little Russian horse, and creeps to the bedroom door.

He will, he decides, make Grandfather a hot milk.

In the hallway, the photographs stare at him, and he in turn stares at mama’s door. He has not been through since the night Grandfather brought him home from Yuri’s, but he knows that Grandfather goes in there at night – not to sleep, but to make the sad baby bird sounds that the boy has started to hear after dark. Inside, a lamp burns; the boy can see the light in the sliver under the door. He drops to his hands and kneels and presses his nose to the crack, like the pet dog he has never been allowed. He thinks: I’ll smell her still, in the air trapped like a tomb. But all he draws into his nostrils is dust and carpet strands.

He is in the kitchen, with the milk pan rattling on the stove, when he hears the familiar click of Grandfather’s heels. A key scratches in the lock, and a flurry of cold air tells him that Grandfather has come in.

Quickly, he fills the mugs and ferries them to that place where the rocking chair sits before the dead gas fire. In the chair, mama’s shawl is sleeping, curled up like a cat.

A voice flurries down the hall, ‘You should be in bed.’

How Grandfather knows he is there, he cannot tell.

‘I know.’

‘Couldn’t you sleep?’

Grandfather appears in the alcove, ruddy face still glistening from the cold. He looks different tonight. He has taken off his overcoat to reveal a slick black suit underneath. Grandfather has never looked as smart as he does in the suit, but it is a sad thing to see a man look so smart. His tie is done up tight and it bunches the loose skin of his neck, leaving a horrid red line like a scar. His hair has oil in it and is combed so you can see every strand. He has had a shave and all of his whiskers, once so prickly and wild, have gone.

‘I see you made the milk.’

‘It was to ward off winter.’

Grandfather’s face cracks in a smile. ‘Like in the story!’

It was one Grandfather told him on the night mama died, of the peasant boy Dimian and his forest home, and how he loved to take his fists to his neighbours and would do almost anything to tempt them to a fight.

Grandfather shuffles into the alcove, and, like a mouse afraid of being trampled, the boy scrambles out of the rocking chair to make space. Before Grandfather settles, though, there is the fire to be made. He keeps the brown paper package nestled in his arm and bends to turn a gauge. Then there is a match; a spark flies up, and the fire is lit.

‘Come on, we can have a biscuit. I don’t think she’d mind if you wanted a biscuit, would she?’

‘Even late at night?’

‘Well, it’s a special kind of night.’

Grandfather retreats to the kitchen, returning with the package under one arm and a biscuit tin in the other. Inside are ten pieces of gingerbread with decorations carved into each: ears of wheat curling around a ragged map, and a star with five points hanging above.

The boy is reaching in with a grubby paw when Grandfather stops him.

‘Maybe we should share one.’

Really, the boy would rather have one all for himself. These are special ones, made with honey, not like the ones with jam you can buy in the baker’s. He feels distinctly more hungry just to see one.

‘Can I have one for my own?’

‘No,’ says Grandfather. ‘They have to last.’

It doesn’t matter, in the end, because Grandfather has just a tiny corner, and the boy can suckle on his piece all night. It is rich and sticky in his mouth, coating his gums so that he will be able to taste it all the way to morning.

‘Did mama make the biscuits?’

Grandfather nods. ‘There’s nine more.’

‘Can I have another?’

‘No.’

He doesn’t ask why. Even so, he realizes he’s being especially careful not to make crumbs.

After a great, honeyed silence: ‘What was it like today, papa?’

Grandfather nestles, and might be readying himself for another fable.

This isn’t the tale, he begins, but an opening. The tale comes tomorrow, after the …

‘Papa, please.’

‘It was quiet, boy. Snow on the cemetery. They brought your mama in a black car. I wanted to lift her down myself but she was too heavy. So the men from the parlour had to help me.’

‘Did you … see her, papa?’

‘Not today, boy.’

‘It’s her in the paper, isn’t it?’

Both sets of eyes drop to the brown paper package in Grandfather’s lap. Somehow, mama is inside. All of her that was, boiled down to nothingness and poured into a little tin cup. Inside that package are all the times she walked him to school, all the dinners she made, all the stories before bedtime. And the promise she made him make.

‘Can I hold her?’

Grandfather offers her up. In his hands, she feels light as the air. She is the same as any package that might come through the door. He puts his ear to her and listens, but she no longer has a voice.

‘When will we do it?’

Grandfather takes her back.

‘Do it?’

‘Take her to that place, in the forest.’

Grandfather’s face is lined, and for a moment the boy thinks he doesn’t understand.

He says, ‘You know, the place where baba went.’

Grandfather shakes his head. ‘Not there,’ says the old man, lifting mama to marvel at her. ‘We’ll find a place here, in the city. A place near your old house. A special spot. Somewhere she loved to take you. And then, every time we want to talk to her, every time we want to hear her voice or see her eyes, we’ll go there, you and me, and listen to the wind. What do you think, boy? Can you think of a place?’

Sitting at Grandfather’s feet, with the prickling heat of the gas fire touching his back, the boy is somehow frozen. His fingers twitch, as if he might reach out for mama once again, but Grandfather’s hands close protectively around her. He picks out Grandfather’s eyes, but they are still so perfectly blue, that the boy thinks he must simply be mistaken.

‘Papa,’ he whispers. ‘She wanted to be with baba …’

‘She told you that, did she?’

The boy feels as if he is shrinking in size, barely big enough to perch on Grandfather’s boots. ‘No, papa, she told you.’

The silence of the deepest snowfall fills the alcove.

‘When?’ Grandfather begins, his voice a-tremble.

‘It was when we came,’ breathes the boy, as if fearful of his own words. ‘You were in the kitchen and mama was crying and, papa, she made you promise.’

Grandfather hardens. ‘Your mama would understand, boy, if you wanted her near, some place she could be with us. I don’t want to take her to that place, boy. Do you?’

Though the boy is uncertain of the precise place mama meant, he has an image in his head. He was not there when the dust of his Grandma sifted through mama’s fingers, but she took him there in later years – and there he saw the fringe of the rolling forest, the tumbledown ruin which was a place of stories and histories as well. One hour out of the city, two hours or more, and the woods are wide and the woods are wild and the woods are the world forever and ever. It is, he knows, a place that baba loved through all of her life, a place mama would go to, over and again, to hear her dead mother whisper in the leaves.

‘You promised, papa.’

Grandfather is silent. The boy wonders: does he know the meaning of a promise? Perhaps a promise is a thing only for little boys and girls, like schoolyards and alphabets and mittens.

‘Sometimes, boy, you make a promise to stop someone’s heart from bleeding.’

It isn’t like that for the boy. He won’t forget sitting at mama’s side and putting his arms around her and making his oath: to look to his papa, to love his papa, to look after him for all of his days.

‘Papa, she’ll be upset.’

His fingers reach for the brown paper. At first, Grandfather lifts it away. Then, he relents. His fingers scrabble at it, find its corners, tear and touch the urn underneath. ‘Papa, you wouldn’t break a promise if mama knew.’

Grandfather’s chest rises, fills with cold air. He breathes it out in great, slow plumes. In the make-believe grate, the gas fire flickers and retreats. ‘You sound like your mother, boy. Papa, papa, papa.’ Each word is like a flint being chipped from his lips: sharp, severe, showering sparks. He bends down, his face eclipsing the boy’s, and there no longer seems any blue in his eyes. His lips are pursed and his brow is furrowed and the boy can see his fingers whitening around mama’s little urn. ‘Over and again, that’s all she said. Take me to the forest, papa. Take me to the forest!’ He rears back, and out of his hands the package tumbles. To the boy, it seems as if the world slows down. Mama’s package turns, end over end, and rolls to a stop in the deep shag near the grate. ‘Well, what if I don’t want to go to the forest?’ Grandfather snarls, whirling around without another look at the boy. ‘This is my home. My life. What if I can’t go back?’

Listening to the snarl still in his voice, the boy crawls across the floor and snatches up mama’s urn. The lid is still in place and he thinks to lift it, peer at what still remains, but instead he turns to see Grandfather disappearing from the alcove. Heavy footsteps tramp back into the kitchen.

He clings to his mama. ‘Why is papa so angry, mama?’

He hears the rattle of pans, the tramp of more footsteps, a single click as if Grandfather is donning his big black jackboots. Only when the tramping dies does he dare venture up, out of the alcove, and into the kitchen door. Inside, Grandfather has not donned his jackboots at all. He is hunched over a pan of milk and his heavy breathing fogs the tenement air.

‘You’re not angry, are you, papa?’

He is; the boy can see that he is. Even when it is not foaming on his lips, it is shimmering in his eyes. At first, he does not reply. He simply breathes in and, by breathing in, seems to force the anger back deep inside him. The darkness evaporates and his eyes sparkle blue all over again.

‘I’m … sorry, boy. Your mama, is she okay?’

The boy offers up the urn. ‘I don’t think it hurt her, papa.’

It is a good thing when Grandfather takes the urn. The boy can feel his hands, cold and wet and scored with lines. They linger a little on the boy’s hand, and it is like a little pat that you might give a dog in the street. When Grandfather pulls his hands away, the boy’s go with them, his fingers entwining with the gnarled old knuckles.

‘Is it a tale before bedtime, boy?’ the old man asks, almost contrite.

The boy nods. ‘And mama can listen too.’

In the bedroom, Grandfather tells him of the little briar rose. It is a German story, and not of their people, but in it are forests the same as theirs, and peasants who might be like them, were it not for different tongues and different kings. In the story a mama and a papa want a baby of their own, but their lives are empty as the tenement today, until one day an enchantment gives them a daughter, the Little Briar Rose. There is a feast, but there is no place at the table for the thirteenth wise woman of the village, and in revenge she makes a prophecy that, on her fifteenth birthday, the Little Briar Rose will open her finger on a spindle and fall into an unending, poisoned sleep.

Grandfather’s voice has the same sound, like feathers being ruffled, that is swiftly becoming familiar. The boy lets it wash over him. His thoughts, punctuated by mourning mamas and walls of thorn grown up to hem in the sleeping girl, wander.

‘Why don’t you want to go to the forest, papa?’ he says, bolting up in bed so that his words pummel straight through the heart of Grandfather’s fable.

This time, the old man is not so angry after all. ‘That, my boy … that’s another story. One,’ he chokes, ‘that your mama never knew.’

‘We’ll take her though, won’t we?’

Grandfather whispers, ‘I’m sorry, boy. I didn’t mean to get cross. I … miss her, that’s all. We’ll take her tomorrow.’

The boy has closed his eyes to sleep, with Grandfather retreating down the hall, when he realizes he is still wrapped up in mama’s shawl. He has to be careful because one day the smell will wear out, so he takes it off and makes a nest in the corner. Then he plucks the Russian horse from the ledge and settles him down in the nest for sleep.

Outside, tiny crystals of snow are twirling on the wind. In the ragged orange of one of the streetlamps a man is hunched over Grandfather’s car. With the door half open, the man rifles inside. But he finds nothing, and then he is gone, leaving the door ajar and the snow curling through.

The boy steals back to bed, whispers goodnight to the Russian horse, and closes his eyes. It blocks out the glow of the streetlamps, but it does not block out the strange, muted whimpers coming from along the hall.

In the morning they have to dress up warm, because it’s winter and today is a day out. There are mittens and scarves that mama made, and big black boots two sizes too big. As Grandfather works them onto the boy’s feet, he tries to find answers in the lines of the old man’s face, but it is hard grappling for an answer when the question remains so out of grasp.

‘Are you going to be okay, papa?’

The last boot goes on, and Grandfather looks up with furrowed eyes. His face is not scored with the same deep crevices as the night before, but this the boy does not brood on, because the night has a kind of magic and makes things all better by morning.

‘Okay?’

‘To go into the forest.’

In response, Grandfather lifts a hat from the edge of the rocking chair and lowers it over his head. It is a ring of brown and black that, so it is said, is made out of bear.

‘We have to do it for mama, don’t we?’

Grandfather nods, with steeliness in his eyes of blue.

The car, Grandfather finds, has been open all night. Snow ices the seats and the steering wheel is rimed in hoarfrost, so that when the boy crawls inside he is colder than he was outside. In his lap sits the little Russian horse – because mama must say goodbye to that poor wooden creature too – and underneath him, his eiderdown for a blanket. It is, Grandfather says, going to be bitter and cold before they are through.

‘Do you know the way, papa?’

Grandfather says, ‘I think I remember.’

‘So you’ve been there before?’

‘Oh, long, long ago, when we did not exist, when perhaps our great-grandfathers were not in the world …’

If it seems like a story is about to begin, it quickly turns to mist. Grandfather scrubs a hole in the windscreen and squints out. ‘The winter might be against us, but you’ve the stomach for an adventure, don’t you, boy?’

It thrills the boy when Grandfather says this, because the boy has never had an adventure, not a proper adventure of the kind he thinks Grandfather must once have had. Those photographs in the tenement spell out a kind of story, and perhaps he would find it as heroic as the fables Grandfather tells, if only he knew how to read it.

‘What if we get hungry?’

Grandfather pats his pockets. ‘I brought us wings of the angel.’

The city streets are banked in grey slush. This snow, Grandfather says, is not for settling. That Grandfather is not always correct is quickly apparent, for once they have left the austere tenements behind, the drifts grow high at the banks and the blacktops are encased in ice as thick as a river.

It is frightening to leave the city. The city is school and the tenement and the miles and miles of empty factories where the boy is forbidden to play. In places, the boy knows, the forests have crept into the city itself, as if all of the streets and squares are held in a giant fist of pines, but outside there is nothing but the dark curtain of woodland and the barren heaths in between. The road weaves across them like an open white vein.

For miles the road is bordered by banks of firs but, deeper in, the trees are older still: sprawling oaks and beech, alders and ash. Once in a while an oak towers over the rest, and those oaks have stories and names all of their own. Somewhere, so deep that Grandfather says it might lie in some other country, stands the plague tree, whose branches cradled an ancient king while death ravaged his kingdom. There are oaks named after battles and tsars and emperors whose empires have long since ceased to exist, but these the boy knows he will never see, for the forest stretches until the very end of the earth and, if you follow its paths, you can never come back home. It would, he knows, be a very great adventure to see the edge of the forest; but mama is gone, and the boy has made a promise: he will not leave Grandfather to drink milk in the tenement alone.

They have gone many miles from the tenement when Grandfather pushes his old jackboot to the floor and turns the car onto a forest track. The branches above, laden with snow, have formed a cavernous roof, so that the trail here is almost naked, only lightly dusted with crystals of frost.

The boy chews his mittens off his hands and suckles on each finger for warmth.

‘Are you so hungry?’

‘No.’

‘We should have brought soup.’

‘I don’t like soup.’

‘You liked your mama’s kapusta.’

‘Which one is that?’

‘Cabbage,’ the old man beams.

There is a long silence.

‘I didn’t like it,’ the boy finally whispers, his head bowed. ‘I only told her I liked it.’

‘Why?’

‘She liked to make it for me, didn’t she, papa?’

‘I’ll make you some.’

‘Not like mama.’

‘No,’ Grandfather whispers, ‘not like mama.’

When they are deep in the wood, Grandfather slows the car. The windows are frosting again on the inside and he rubs them with his sleeve to make sure he can see the trail. ‘It must be somewhere near,’ he says.

‘Here?’

There is a trembling in Grandfather’s voice; it might be fancy, but he thinks it is because of more than the cold. The boy watches him, but Grandfather is hunched over the wheel, squinting through the ever-decreasing hole in the windscreen, and betrays not a flicker. He guides the car to the very edge of the track, cutting the engine before they’ve stopped rolling.

‘Come on, boy. We’ll know it when we see it.’

It is easy, now, to see why Grandfather did not want to come to the forest. The trees have the visages of men. They leer, and grope, and they surround. Colonies of birds with watchful black eyes line the treetops.

When he climbs out of the car, the frost is the first thing to assault him; the trees simply stay where they are, watching, and for a moment that is the most terrible thing of all. Grandfather waits between the trees, and by the time the boy catches up his face has blanched as white as the ice-bound branches around.

‘Are you okay, papa?’

‘You don’t have to keep asking, boy. We’ll see it done and then be off home.’

They set off, Grandfather – in his eagerness to see it done – always two strides ahead. The trail leads them into darker reaches of the woodland, but everywhere shimmers with the same kind of spectral light, the sunlight trapped beneath the branches by a canopy of snow. This forest they walk in is a graveyard, and fitting perhaps for mama’s end.

‘The urn!’ Grandfather mutters, opening his empty hands. ‘Stay here.’

He sweeps around and, with shoulders hunched up, barrels back down the trail.

Now the boy is alone. He stands in the middle of the track and watches his breath rise. The tips of his ears and the end of his nose tingle. He has never heard silence quite like this. He thinks that, if he coughed, it would break some secret forest rule. It would be so loud the blackbirds would scatter from their roosts and the wild cats come hurtling from their hidings.

It smells of outside, of earth and bark and crystal-clear water.

He doesn’t move until Grandfather returns, mama’s package held between hands that have lost their gloves and look raw.

‘Were you scared?’

He shakes his head.

‘I was afraid, boy, the first time I found myself in the wilderness alone.’

The boy wants to ask more, because it sounds like there’s a story in that, one quite unlike the fables Grandfather spins at night, but instead the old man tramps on and he is compelled to follow.

Before they have gone far, the trees thin, then peter out altogether. The forester’s trail turns to follow the edge of the woodland, along a ridge that overlooks a clean, white pasture. In the roots of one of the tumbled yews, there is a big yellow depression and a trail of yellow droplets running away from it.