Полная версия

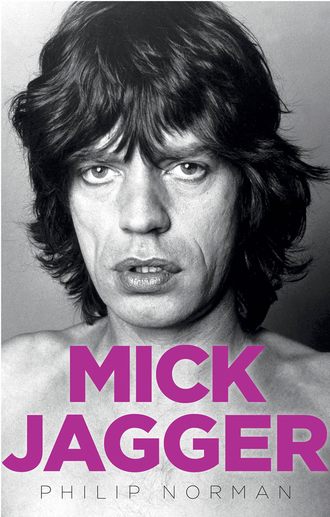

Mick Jagger

There might seem no possible meeting point between suburban Kent with its privet hedges and slow green buses, and the Mississippi Delta with its tar-and-paper cabins, shanty towns and prison farms; still less between a genteelly raised white British boy and the dusty black troubadours whose chants of pain or anger or defiance had lightened the load and lifted the spirits of untold fellow sufferers under twentieth-century servitude. For Mike, the initial attraction of the blues was simply that of being different – standing out from his coevals as he already did through basketball. To some extent, too, it had a political element. This was the era of English literature’s so-called angry young men and their well-publicised contempt for the cosiness and insularity of life under Harold Macmillan’s Tory government. One of their numerous complaints, voiced in John Osborne’s play Look Back in Anger, was that ‘there are no good, brave causes left’. To a would-be rebel in 1959, the oppression of black musicians in pre-war rural America was more than cause enough.

But Mike’s love of the blues was as passionate and sincere as he’d ever been about anything in his life, or perhaps ever would be. In crackly recordings, mostly made long before his birth, he found an excitement – an empathy – he never had in the wildest moments of rock ’n’ roll. Indeed, he could see now just what an impostor rock was in so many ways; how puny were its wealthy young white stars in comparison with the bluesmen who’d written the book and, mostly, died in poverty; how those long-dead voices, wailing to the beat of a lone guitar, had a ferocity and humour and eloquence and elegance to which nothing on the rock ’n’ roll jukebox even came close. The parental furore over Elvis Presley’s sexual content, for instance, seemed laughable if one compared the pubescent hot flushes of ‘Teddy Bear’ and ‘All Shook Up’ with Lonnie Johnson’s syphilis-crazed ‘Careless Love’ or Blind Lemon Jefferson’s nakedly priapic ‘Black Snake Moan’. And what press-pilloried rock ’n’ roll reprobate, Little Richard or Jerry Lee Lewis, could hold a candle to Robert Johnson, the boy genius of the blues who lived almost the whole of his short life among drug addicts and prostitutes and was said to have made a pact with the devil in exchange for his peerless talent?

Though skiffle had brought some blues songs into general consciousness, the music still had only a tiny British following – mostly ‘intellectual’ types who read leftish weeklies, wore maroon socks with sandals and carried their change in leather purses. Like skiffle, it was seen as a branch of jazz: the few American blues performers who ever performed live in Britain did so through the sponsorship – charity, some might say – of traditional jazz bandleaders like Humphrey Lyttelton, Ken Colyer and Chris Barber. ‘Humph’ had been bringing Big Bill Broonzy over as a support attraction since 1950, while every year or so the duo of Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee attracted small but ardent crowds to Colyer’s Soho club, Studio 51. After helping give birth to skiffle, Barber had become a stalwart of the National Jazz League, which strove to put this most lackadaisical of the arts on an organised footing and had its own club, the Marquee in Oxford Street. Here, too, from time to time, some famous old blues survivor would appear onstage, still bewildered by his sudden transition from Chicago or Memphis.

Finding the blues on record was almost as difficult. It was not available on six-shilling and fourpenny singles, like rock and pop, but only on what were still known as ‘LPs’ (long-players) rather than albums, priced at a daunting thirty shillings (£1.50) and up. To add to the expense, these were usually not released on British record labels but imported from America in their original packaging with the price in dollars and cents crossed out and a new one in pounds, shillings and pence substituted. Such exotica was, of course, not stocked by record shops in Dartford or even in large neighbouring towns such as Chatham or Rochester. To find it, Mike and Dick had to go to up to London and trawl through the racks at specialist dealers like Dobell’s on Charing Cross Road.

Their circle at Dartford Grammar School included two other boys with the same recondite passion. One was a rather quiet, bookish type from the arts stream named Bob Beckwith; the other was Mike’s Wilmington neighbour, the science student Alan Etherington. In late 1959, during Mike’s first term in the sixth form, the four decided to form a blues band. Bob and Dick played guitar, Alan (a drummer and bugler in the school cadet force) played percussion on a drum kit donated by Dick’s grandfather, and Mike was the vocalist.

Their aim was not to earn money or win local fame, like Danny Rogers and the Realms, nor even to pull girls. Mike in particular – as Alan Etherington recalls – already had all the ardent female followers he could wish for. The idea was simply to celebrate the blues and keep it alive amid the suffocating tides of commercial rock and pop. From first to last, they never had a single paid gig or performed to any audience larger than about half a dozen. Dartford Grammar gave them no opportunities to play or encouragement of any kind, even though they were effectively studying a byway of modern American history; Alan Etherington recalls ‘a stand-up row’ with the school librarian after requesting a book by blues chronicler Paul Oliver as background reading for the quartet. They existed in a self-created vacuum, making no effort to contact kindred spirits in Kent or the wider world – hardly even aware that there were any. In Dick Taylor’s words, ‘We thought we were the only people in Britain who’d ever heard of the blues.’

CHAPTER TWO

The Kid in the Cardigan

Mike Jagger seemed living proof of the unnamed band’s determination to go nowhere. He remained firm in his refusal to play a guitar, instead just standing there in front of the other three, as incomplete and exposed without that instantly glamorising, dignifying prop as if he’d forgotten to put on his trousers. The singing voice unveiled by his prodigious lips and flicking tongue was likewise an almost perverse departure from the norm. White British vocalists usually sang jazz or blues in a gravelly, cigarette-smoky style modelled – vainly – on Louis ‘Satchmo’ Armstrong. Mike’s voice, higher and lighter in tone, borrowed from a larger, more eclectic cast; it was a distillation of every Deep Southern accent he’d ever heard, white as much as black, feminine as much as masculine; Scarlett O’Hara, plus a touch of Mammy from Gone with the Wind and Blanche DuBois from A Streetcar Named Desire as much as Blind Lemon Jefferson or Sonny Boy Williamson.

Unencumbered by a guitar – mostly even by a microphone – he had to do something while he sang. But the three friends, accustomed to his cool, non-committal school persona, were amazed by what he did do. Blues vocalists traditionally stood or, more often, sat in an anguished trance, cupping one ear with a hand to amplify the sonic self-flagellation. When Mike sang the blues, however, his loose-limbed, athletic body rebutted the music’s melancholic inertia word by word: he shuffled to and fro on his moccasins, ground his hips, rippled his arms and euphorically shook his shaggy head. Like his singing, it had an element of parody and self-parody, but an underlying total conviction. A song from his early repertoire, John Lee Hooker’s ‘Boogie Chillen’, summed up this metamorphosis: ‘The blues is in him . . . and it’s got to come out . . .’

Practice sessions for the non-existent gigs were mostly held at Dick Taylor’s house in Bexleyheath or at Alan Etherington’s, a few doors along from the Jaggers. Alan owned a reel-to-reel tape recorder, a Philips ‘Joystick’ (so named for its aeronautical-looking volume control) on which the four could preserve and review their first efforts together. The Etherington home boasted the further luxury of a Grundig ‘radiogram’, a cabinet radio-cum-record-player with surround sound, an early form of stereo. Dick and Bob Beckwith did not have custom-built electric guitars, only acoustic ones with metal pickups screwed to the bodies. Beckwith, the more accomplished player of the two, would plug his guitar into the radiogram, increasing its volume about thirtyfold.

At Dick’s, if the weather was fine, they would rehearse in the back garden – the future lord of giant alfresco spaces and horizonless crowds surveying a narrow vista of creosoted wood fences, washing lines and potting sheds. Dick’s mum, who sometimes interrupted her housework to watch, told Mike from the start that he had ‘something special’. However small or accidental the audience, he gave them his all. ‘If I could get a show, I would do it,’ he would remember. ‘I used to do mad things . . . Get on my knees and roll on the floor . . . I didn’t have inhibitions. It’s a real buzz, even in front of twenty people, to make a complete fool of yourself.’

Though Joe and Eva Jagger had no comprehension of the blues or its transfiguring effect on their elder son, they were quite happy for his group to practise at ‘Newlands’, in either his bedroom or the garden. Eva found his singing hilarious and would later describe ‘creasing up’ with laughter at the sound of his voice through the wall. His father’s only concern was that it shouldn’t interfere with his physical training programme. Once, when he and Dick Taylor were leaving for a practise session elsewhere, Joe called out, ‘Michael . . . don’t forget your weight training.’ Mike dutifully turned back and spent half an hour in the garden with his weights and barbells. Another time, he arrived for band practice distraught because he’d fallen from one of the tree ropes at home and bitten his tongue. What if it had permanently damaged his singing voice? ‘We all told him it made no difference,’ Dick Taylor remembers. ‘But he did seem to lisp a bit and sound a bit more bluesy after that.’

Building up a repertoire was a laborious process. The usual way was for Mike and Dick to bring a record back from London, and the four to listen to it over and over until Bob had mastered the guitar fills and Mike learned the words. They did not restrict themselves to blues, but also experimented with white rock and pop songs, like Buddy Holly’s, which had some kinship with it. One of the better performances committed to the Philips Joystick was of ‘La Bamba’, whose sixteen-year-old singer–composer Ritchie Valens had died in the same plane crash that killed Holly in February 1959. Its Latino nonsense words being impossible to decipher, no matter how often one replayed the record, Mike simply invented his own.

The Joystick’s inventory dramatically improved with their discovery of harder-edged electric blues, as played by John Lee Hooker, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Memphis Slim and Howlin’ Wolf. A discovery of almost equal momentousness was that many of these alluring names could be traced to the same source, the Chess record label of Chicago. Founded in the 1940s by two Polish immigrant brothers, Leonard and Phil Chess, the label had started out with jazz but become increasingly dominated by what was then called ‘race’ music – i.e., for exclusively black consumption. Its most notable early acquisition had been McKinley Morganfield, aka Muddy Waters, born in 1913 (the same year as Joe Jagger) and known as ‘the father of the Chicago Blues’ for tracks like ‘Hoochie Coochie Man’, ‘I Just Want to Make Love to You’ and his theme song, ‘Rollin’ Stone’. His album At Newport 1960, capturing his performance at the 1960 Newport Jazz Festival, was the first album Mike Jagger ever bought.

In 1955, Chess signed St. Louis-born Charles Edward Anderson – aka Chuck – Berry, a singer-songwriter-guitarist who combined the sexiness and cockiness of R&B with the social commentary of country and western, the lucid diction of black balladeers like Nat ‘King’ Cole and Billy Eckstine, and a lyrical and instrumental nimbleness all his own. Soon afterwards Berry made an effortless crossover from ‘race’ music to white rock ’n’ roll with compositions such as ‘Johnny B. Goode’, ‘Sweet Little Sixteen’ and ‘Memphis, Tennessee’ that were to become its defining anthems. Long before he ever heard a Chuck Berry song, Mike’s voice had some of the same character.

After a long and fruitless search for Chess LPs up and down Charing Cross Road, he discovered they could be obtained by mail order directly from the company’s Chicago headquarters. It was a gamble, since prepayment had to be enclosed and he had no idea whether he’d like the titles he ordered – if they ever materialised at all. But, after a lengthy wait, flat brown cardboard packages with American stamps began arriving at ‘Newlands’. Some of the covers had been badly chewed up in transit and not all the music lived up to his expectations. But the albums in themselves were splendiferous status symbols. He took to carrying around three or four at once tucked under one arm, a fashion accessory as much as his gold-flecked jacket and moccasins. Alan Dow, who’d rejected him as a vocalist for Danny Rogers and the Realms, witnessed one such almost regal progress across the school playground.

In summer 1961, he sat his A-level exams, passing in English and history but, surprisingly, failing in French. He considered becoming a schoolteacher in his father’s – and grandfather’s – footsteps, and toyed with the idea of journalism and (unmentionably to his parents) disc-jockeying on Radio Luxembourg. Leafing through the pop music papers one week, he spotted an advertisement by a London record producer named Joe Meek, inviting would-be deejays to submit audition tapes. He clipped the ad and kept it, but – perhaps fortunately – didn’t follow it up. Meek later produced several British pop classics, all from his small north London flat, but was notorious for trying to seduce the prettier young men who crossed his path.

Instead, somewhat against expectations, Mike Jagger joined the 2 per cent of Britain’s school leavers in that era who went on to university. Despite those clashes over uniform, his headmaster, Lofty Hudson, decided he was worthy of the privilege and, in December 1960, well before he had sat his A-levels, supplied a character reference putting the best possible gloss on his academic record. ‘Jagger is a lad of good general character,’ it read in part, ‘although he has been rather slow to mature. The pleasing quality which is now emerging is that of persistence when he makes up his mind to tackle something. His interests are wide. He has been a member of several School Societies and is prominent in Games, being Secretary of our Basketball Club, a member of our First Cricket Eleven and he plays Rugby Football for his House. Out of school he is interested in Camping, Climbing, Canoeing, Music and is a member of the Local Historical Association . . . Jagger’s development now fully justifies me in recommending him for a Degree course and I hope you will be able to accept him.’

Though in no sense hyperbolic, the head’s letter did the trick. Conditional on two A-level passes, Mike was offered a place at the London School of Economics to begin reading for a BSc degree in the autumn of 1961. He accepted it, albeit without great enthusiasm. ‘I wanted to do arts, but thought I ought to do science,’ he would remember. ‘Economics seemed about halfway in between.’

At that time, Britain’s university entrants were not forced to run themselves into debt to the government to pay for their tuition, but received virtually automatic grants from local education authorities. Kent County Council gave Mike £350 per annum, which at a time of almost zero inflation was more than enough to cover three years of study, especially as he would continue living at home and travel up each day by train to the LSE’s small campus in Houghton Street, off Kings-way. Even so, it was clearly advisable to earn some money during the long summer holiday between leaving school and starting there. His choice of job sheds interesting light on a character always thought to have been consumed by selfishness, revealing that until his late teens at least he had a caring and altruistic side that made him very much his father’s son.

For several weeks that summer, he worked as a porter at a local psychiatric institution. Not Stone House – that would have been too perfect – but Bexley Hospital, a similarly grim and sprawling Victorian edifice locally nicknamed ‘the Village on the Heath’ because until recently, in the interests of total segregation, its grounds had included a fully functioning farm. He earned £4.50 per week, not at all a bad wage for the time, though he clearly could have chosen an easier job, both physically and emotionally. He was to be remembered by patients and staff alike as unfailingly kind and cheerful. He himself believed the experience taught him lessons about human psychology that were to prove invaluable throughout his life.

It was at Bexley Hospital, too, by his own account, that he lost his virginity to a nurse, huddled in a store cupboard during a brief respite from pushing trolleys and taking round meals: the furthest possible extreme from all those luxury hotel suites of the future.

A STUDENT AT the London School of Economics in 1961 enjoyed a prestige only slightly below that of Oxford or Cambridge. Founded by George Bernard Shaw and the Fabians Beatrice and Sidney Webb, it was an autonomous unit of London University whose past lecturers had included the philosopher and pacifist Bertrand Russell and the economist John Maynard Keynes. Among its many celebrated alumni were the Labour chancellor of the exchequer Hugh Dalton, the polemical journalist Bernard Levin, the newly elected president of the United States, John F. Kennedy, and his brother (and attorney general) Robert.

It was also by long tradition Britain’s most highly politicised seat of learning, governed largely by old-school right-wingers but with an increasingly radical student population and junior staff. Though its heyday as a cauldron of youthful dissent was still half a dozen years in the future, LSE demonstrators already took to the streets on a regular basis, protesting against foreign atrocities like the Sharpeville Massacre in South Africa and supporting their elder statesman Bertrand Russell’s Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. One of Mike’s fellow students, the future publisher and peer Matthew Evans, had won his place despite passing only one A-level and with a far more modest cache of O-levels, including woodwork. More important was that he’d taken part in the famous CND protest march to the nuclear weapons research establishment at Aldermaston, Berkshire.

On the same BSc degree course was Laurence Isaacson, in later life a highly successful restaurant tycoon who would quip that if he’d sung or played an instrument his future might have been very different. Born in Liverpool, he had attended Dovedale Primary School like John Lennon and George Harrison and then, like Lennon, gone on to Quarry Bank High School; now here he was actually sitting next to another future legend of rock. The two were doing the same specialist subject, industry and trade, for the second paper in their finals. ‘That meant that if Jagger missed a lecture, he’d copy out my notes, and if I missed one, I’d copy out his,’ Isaacson says. ‘I seem to recall he used to do most of the copying.’

Like Evans, Isaacson remembers him as ‘obviously extremely bright’ and easily capable of achieving a 2:1 degree. At lectures, he was always quiet and well mannered and spoke ‘like a nice middle-class boy . . . The trouble was that it still all felt a bit too much like school. You had to be very respectful to the tutors and, of course, never answer back. And the classes were so small that they always had their eye on you. I remember one shouting out, “Jagger . . . if you don’t concentrate, you’re never going to get anywhere!”’

Barely two years into a new decade, London had already taken huge strides away from the stuffy, sleepy fifties – though the changes were only just beginning. A feeling of excitement and expectation pulsed through the crusty old Victorian metropolis at every level: from its towering new office blocks and swirling new traffic overpasses and underpasses to its impudent new minicars, minivans and minicabs and ever-lengthening rows of parking meters; from its new wine bars, ‘bistros’ and Italian trattorias to its sophisticated new advertisements and brand identities and newly launched, or revivified, glossy magazines like Town, Queen and Tatler; from its young men in modish narrower trousers, thick-striped shirts and square-toed shoes to its young women in masculine-looking V-necked Shetland sweaters, 1920s-style ropes of beads, black stockings and radically short skirts.

Innovation and experimentation (once again the merest amuse-bouche from the banquet to come) flourished at new theatres like Bernard Miles’s Mermaid and Joan Littlewood’s Theatre Royal, Stratford East; in the plays of Arnold Wesker and Harold Pinter; in mould-shattering productions like Peter Cook, Dudley Moore, Alan Bennett and Jonathan Miller’s Beyond the Fringe and Lionel Bart’s Oliver! The middle-aged metropolitan sophisticates whose posh accents always ruled London’s arts and media now began to seem laughably old-fashioned. An emergent school of young painters from humble families and provincial backgrounds – including Yorkshire’s David Hockney, Essex’s Allen Jones and Dartford’s Peter Blake – were being more talked and written about than any since the French Impressionists. Vogue magazine, the supreme arbiter of style and sophistication, ceased employing bow-tied society figures to photograph its model girls, instead hiring a brash young East End Cockney named David Bailey.

Only in popular music did excitement seem to be dwindling rather than growing. The ructions that rock ’n’ roll had caused among mid-fifties teenagers were a distant, almost embarrassing memory. Elvis Presley had disappeared into the US army for two years, and then emerged shorn of his sideburns, singing ballads and hymns. The American music industry had been convulsed by scandals over payola and the misadventures of individual stars. Buddy Holly and Eddie Cochran were dead; Little Richard had found God; Jerry Lee Lewis had been engulfed in controversy after bigamously marrying his thirteen-year-old cousin; Chuck Berry had been convicted on an immorality charge involving a teenage girl. The new teenage icons were throwbacks to the crooner era, with names like Frankie and Bobby, chosen for prettiness rather than vocal talent, and their manifest inability to hurt a fly (or unbutton one). The only creative sparks came from young white songwriters working out of New York’s Brill Building, largely supplying black singers and groups, and from the black-owned Motown record label in Detroit: all conclusive proof that ‘race’ music was dead and buried.

Such rock idols as Britain had produced – Tommy Steele, Adam Faith, Cliff Richard – had all heeded the dire warnings that it couldn’t possibly last and crossed over as soon as possible into mainstream show business. The current craze was ‘Trad’, a homogenised version of traditional jazz whose bands dressed in faux-Victorian bowler hats and waistcoats and played mainstream show tunes like Cole Porter’s ‘I Love You, Samantha’ and even Rodgers and Hammerstein’s ‘March of the Siamese Children’. The wild, skirt-twirling rock ’n’ roll jive had given way to the slower, more formal Stomp, which involved minimal bodily contact between the dancers and tended to come to a respectful halt during drum solos.

In short, the danger seemed to have passed.

BARELY A MONTH into Mike’s first term at LSE, he met up with Keith Richards again and they resumed the conversation that had broken off in the Wentworth County Primary playground eleven years earlier.

The second most important partnership in rock music history might never have happened if either of them had got out of bed five minutes later, missed a bus, or lingered to buy a pack of cigarettes or a Mars bar. It took place early one weekday on the ‘up’ platform at Dartford railway station as they waited for the same train, Mike to get to Charing Cross in London and Keith to Sidcup, four stops away, where he was now at art college.