Полная версия

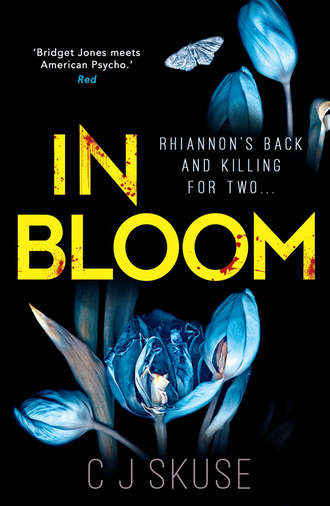

In Bloom

I couldn’t take it in. I was sure she was dead. She’s our miracle.

My big tough boxer dad, crying his eyes red.

Someone up there helped us out that day, that’s for sure.

My mum says little in the docu – she just echoes Dad, maintaining her rabbit-in-the-headlights stare. There’s footage of her giving me a hug outside the hospital when I was released. I missed her hugs as I got older.

There was some home movie footage of the kids who died – two-year-old Jack blowing out his candles. Kimmy in her dad’s arms in the maternity unit. Ashlea in red boots in the snow. The twins eating ice cream. Their mum did Britain’s Got Talent last year but a sob story only takes you so far if you can’t sing for shit.

There’s old news footage from before the presenters went grey – footage of people laying flowers outside Number 12. The sounds of wailing parents as they fight to get through the police cordon. The glistening doormat. Three little stretchers. And then the money shot – me all limp, wrapped inside the blood-stained Peter Rabbit blanket.

Then there are the photo-calls of me coming out of hospital in my wheelchair, weeks later, bandage wrapped tightly around my bald head.

Me in my beanie hat being given the huge teddy bear on This Morning.

My first day at school, Dad wheeling me into the front office and us stopping so the press could take our photos.

Giving the thumbs up on my first day of secondary school.

Thumbs up again after my GCSE results.

The ‘Hasn’t She Done Well?’ front page of the Daily Mirror, with me starting my A Levels and talking about wanting to be a writer.

There was an interview with the shrink – Dr Philip Morrison – who had treated the murderer, Antony Blackstone, for his psychotic rages.

You had one job, Phil.

‘He was a ticking bomb,’ said Phil. ‘Allison’s family knew the marriage was not a happy one – there were signs that he was controlling and abusive. He’d call her incessantly. Track her movements. Even monitored what she was eating so she didn’t put on weight. Her sister had begged her to leave him and one day Allison found the courage. It appeared – at first – to be a mutual arrangement which Blackstone accepted. But it lit the spark in the powder keg.’

Phil was the one who diagnosed me with PTSD after Priory Gardens, even though Mum swore it was ‘growing pains’ and, as I got older, ‘hormones’. He always gave me a Scooby Doo sticker after a session. It’s one of the more depressing parts of growing up – we don’t get stickers anymore.

There’s a playground where the house used to stand now and a plaque on a sundial beside the slide bearing the names of all the kids. Mrs Kingwell’s name too. My name isn’t there of course, being the lucky one.

When Dad talks about it, I can feel his sadness. Otherwise, I don’t feel anything. I can’t even hate Blackstone, cos he’s dead.

The closing footage on the documentary is me and Seren playing with the Sylvanians in the rehab centre. The boxes are dotted all around, wrapped in big bows. I’m lying in my bed and watching her, moving the figures about on my tummy and Seren is telling me some story about mice. It strikes me hard how she’s the only person I have left in this world – the only person who knows the real me. Even though she despises me these days, I do miss her.

Priory Gardens was the spark in my powder keg. The reason Mum got sick. The reason Dad gave up. The reason I have little emotional reaction to anything except Death. I can’t feel unless I’m killing. Then I feel everything.

We’ve had another note. This time I caught sight of the person who posted it as he was loping off up the seafront – a big guy in blue jeans, hoody. No other wording – just the same again. ‘To my Sweet Messy House’. And a number.

‘I don’t want to fucking talk to you!’ I screamed through the letterbox, screwing up the note and scuffing back into the lounge. Gordon Ramsay had started on one of the high channels – he was counselling a crying chef who’d lost all his microwaves.

*

Jim’s been in – the estate agent says two couples are interested in Craig’s flat. The forensics have finished, so he’s released it for sale to start paying the lawyers. One of the couples is expecting. I imagine them walking around, hand in hand, looking in our wardrobes, talking about the ‘nice views from the balcony’. Looking inside the cupboards that I watched Craig build, that autumn we first met. We got Tink from the RSPCA that autumn, a little warm ball of toffee ice cream who licked my cheek and stopped shaking the moment I held her. It’s all I can do to prise her away from Jim these days.

Saturday, 28th July – 11 weeks, 6 days

1. Cafés that pre-butter toast or toasted tea cakes.

2. The guy that keeps posting illegible notes through our front door.

3. Weathermen who stand in hurricanes strong enough to blow cataracts from their eyes and ‘can’t believe how strong the wind is’.

My Bible doesn’t seem to be able to offer me any guidance on feeling less tilted than I do at the moment, aside from ‘Offer yourself up to the Lord’ or ‘God’s mighty hand will lift you up if you just believe.’ Not a bad read though. That Delilah was a bit of a head case.

Marnie texted – Fancy a trip to the Mall to find your maternity clothes? I can chauffeur – Marn x

I was still annoyed by the fact it had taken her so long to ask but she was offering to drive, so gift horses and all that.

The traffic was bad on the way up but Marnie was in a good mood and when you’ve got stuff to chat about, it doesn’t feel like you’ve been stuck in a car for hours. We talked about our respective families and how dead they all are, how I barely speak to Seren in Seattle and how she barely speaks to her brother Sandro who lives in Italy and runs residential art classes.

‘How come you don’t speak to him?’ I asked.

‘Oh you know how it is, you grow apart as you get older, don’t you?’ she said and left it at that. ‘Isn’t that what it’s like with you and Seren?’

‘No, Seren says I’m a psychopath like our dad.’

Marnie glanced away from the traffic. ‘Are you?’

I shrugged. ‘Bit.’

She laughed. Probably thought I was joking, I don’t know. We played the number plate game and she had cola bottles and sour cherries in her glovebox and Beyoncé on the Bluetooth so I was happy.

‘Tim doesn’t like me eating sweets at home,’ she said, then bit down on her lip like she shouldn’t have said it. ‘He’s got me into blueberries so I eat those instead. They’re incredibly good for you.’

‘Yeah I’ve had the blueberry lecture from Elaine. She makes these vile blueberry granola bars for me to peck at if I’m hungry. They taste like old teabags and feet. Why doesn’t Tim let you have sweets?’

‘He worries about diabetes and things.’

‘Halo’ came on and much to my intense delight, Marnie turned it up to full vol. ‘This is my favourite.’

‘Mine too,’ I lied. Mine was actually ‘6 Inch’ from the Lemonade album but I didn’t want to break the moment.

Before too long we were singing. Unashamedly. Not even holding back on the big notes. It was so easy, so immediate. Like we’d been friends for years. All thanks to Queen Bey herself. We made it to the end of the song—

Then her phone rang.

It rang twice, both times Tim, first asking where she was and who she was with (I had to say ‘Hello’) and the second time to ask if they had any ant powder. Marnie did most of the talking and I noticed she kept asking if things were all right. ‘Chicken Kievs for tea if that’s all right?’ and ‘Back about six if that’s all right?’ His voice reminded me of Grandad’s.

‘My grandad never let my nanny have any freedom either,’ I said when she had ended the call.

‘No, it’s not like that,’ she said, for once without a little smile or a giggle at the end of her sentence. ‘He just worries about me, especially now.’

‘My nan blamed me for my grandad’s death. She said I’d killed him.’

Marnie glanced over, briefly, as she indicated to come off the motorway. We came to a halt at the traffic lights. ‘Why did she say that?’

‘Cos I was there when it happened. He had a heart attack while he was swimming. He liked wild swimming. I was on the bank, watching him and I didn’t do anything. He drowned.’

‘Oh my god,’ she said, as the lights went green. ‘How old were you?’

‘Eleven.’

‘Well of course you couldn’t have done anything, you were only a child. That’s a terrible thing for an adult to put on such a young person.’

‘Yeah, I guess. She’d taken me to meet Mr Blobby that summer too. Proper sadist, my nanny.’

She didn’t laugh but patted my knee. I was going to tell her. The words were locked and loaded and ready to come out – I was going to tell her how I’d watched my grandad hit Seren that morning for not bringing in the eggs and how much I wanted to kill him. To push him down the stairs or into the slurry or to drive an axe right down deep into the back of his neck while he was stacking the logs. But I didn’t say a word. I didn’t tell her that watching my grandad drown had been an exquisite pleasure. I kept that to myself because Marnie had patted my knee and seemed to care that I was the innocent one. And I liked the feeling. I wanted to hold onto it.

The Mall was heaving with people and though Marnie was more than happy to mooch about trying things on, I couldn’t find a single atom of my body that cared about maternity clothes. She didn’t buy a thing, even stuff she said she loved. Dresses she’d point out as ‘stunning’ or ‘exquisite’ she would hold up against herself then return them to the peg. When I called her on it she said, ‘Oh I’ll probably never wear it again anyway. It’s a waste of money.’

‘Bet he gives you an allowance every week, doesn’t he?’

‘No,’ she said. ‘This is my money.’

‘My nanny used to get an allowance and she’d never spend it either. She used to squirrel it away. I never found out why.’

We hit the John Lewis café for lunch. I got a lemon and vanilla ice cream crepe, Marnie got a salad.

‘Get some carbs down you for god’s sake,’ I said as we stood in the line waiting for the assistant to scoop my vanilla. ‘You’re drooling over mine.’

‘I shouldn’t,’ she said, biting her lip.

‘Why not?’

‘Slippery slope, isn’t it?’

Marnie’s phone was out next to her plate the moment we sat down.

‘So tell me more about Tim then,’ I said. ‘What’s he like?’

Again, her manner changed, her voice lowered. ‘He’s Area Manager for that plastic shelving place on the ring road. Quite long hours but he loves it.’

‘What did you do before you went on maternity?’

‘Admin, council refuse department. Only for the last seven months though. Before that I was a dancer.’

‘What kind of dancer?’

‘Ballet and tap. I taught classes.’

‘Why did you stop?’

‘Well, we moved down here for Tim’s job and then I got pregnant.’

‘But you could go back to it someday?’

‘Doubt it. The money’s better at the council anyway. I did love it though.’

Her phone rang. ‘Sorry, hang on… Hiya… Yep… that’ll be nice… sounds good… Yeah, Rhiannon’s still with me. Need me to pick anything up?… Okay… Love you.’ She put the phone down.

‘Tim?’ I said, chewing my crepe.

‘Yeah,’ she smiled, theatrically rolling her eyes. ‘He’s booking the hotel for next weekend. Our sixth anniversary. Bit of a babymoon.’

‘Six years,’ I said. ‘That’s wood, isn’t it?’

‘I don’t know,’ she said.

‘A wooden garden ornament or something?’

‘He’s not into ornaments. I inherited a load of china ones from my mum but I’m not allowed to display them.’

‘Not allowed?’

‘Well, it’s only a few ballerinas with their buns broken off. I used to play with them as a kid. My mum bought me one each time I passed an exam.’

I pride myself on a few things: my ability to defend the defenceless, to maintain The Act that I am a normal human being in polite society, and to trace vulnerability in people. I can sniff it out as easily as curry plant in a garden full of roses. And it was coming off Marnie in waves.

‘Are you sure it wasn’t Tim who made you give up dancing?’

She frown-laughed. ‘No, my choice. He was right though; the pay was crap.’ She stroked her bump. ‘No regrets. I have everything I want. A great house and steady job and a healthy baby boy coming soon—’

Grandad used to fill Honey Cottage with his stuffed animals. Weasels and stoats and tiny birds that he’d shot out of trees with a pellet gun. Nanny never liked them. She said they looked like they were in eternal pain. Nanny liked Capo di Monte teapots and cherubs and porcelain roses, but she kept them in bubble wrap in boxes because ‘they keep getting smashed’.

‘I think you should put the ballerinas on display,’ I told Marnie, mopping up my vanilla puddle with my crepe.

‘It’s no big deal,’ she said, tucking into her salad again.

I was going to ask what she meant but she jumped into another conversation as she stabbed her lettuce. ‘So will you stay on with your in-laws when the baby comes?’

Before I’d even opened my mouth, her phone rang again.

‘Hiya, Hun… uh yeah I can pick some up… okay… yeah, still with Rhiannon. Oh great. Yep, I will. Thanks, love, see you later. Love you… Bye.’

My eyebrows rose.

‘We need potatoes. Where were we?’

‘We were talking then the guy you live with called twice about nothing.’

She carried on crunching her lettuce. We sat in silence, watching mums struggling with pushchairs, kids skipping along beside them, old friends meeting and hugging. On the next table a dad was talking his two-year-old daughter through the menu choices, like he was teaching her to read. Their meals arrived – he cut up her chips and taught her to blow on them. The child wanted him to feed her instead of doing it for herself so he was eating his meal with one hand, feeding her with the other.

A while later, our conversation restarted and we were back being easy together – I was telling her about WOMBAT and begging her to come along to the next meeting to save me from certain kindness brainwashing. I told her all about the little names I’d given them all—

When her phone rang again. I saw the screen – Tim calling.

She gurned apologetically. ‘This is the last time, I promise… Hi, love… yeah, I think so… oh, that’s good, well done… yeah that sounds—’

I grabbed the phone out of her hand and hit the End Call button.

Marnie shot up, grabbing at her phone. ‘Why did you do that?!’

‘Well for one because it’s rude when you’re talking to someone—’

‘He’s on his lunch break! It’s the only time he can call!’

‘—and two, your husband’s being an endless little bitch.’

She called him back and spent the next ten minutes apologising and eating shit like an absolute pro while I finished my crepe and sipped my tea. When she came back to the table she breathed out long and slow.

‘He’s fine. He’s fine.’

‘Thank god,’ I said, still chewing. ‘I was so worried.’

‘Why did you do that, Rhiannon?’

‘Cos you’re sleeping with the enemy. I staged an intervention.’

‘Please don’t ever do that again.’

A silence fell.

‘Allison, the childminder at Priory Gardens, she was a battered wife.’

‘I’M NOT A BATTERED WIFE!’ she shouted.

Faces looked. Marnie sank down in her seat.

‘I never said you were.’

‘You don’t understand him, I’m okay with it.’

‘Make me understand it. I dare you.’

Marnie frowned. ‘It’s actually none of your business actually.’

‘Two actuallys.’

‘I don’t care.’

‘Show me your phone.’

‘What?’

‘Show me your phone.’

‘No.’

I grabbed it out of her hand again and she tried to snatch it back.

‘Give it to me. Rhiannon! Now, I want it, give it!’

‘Uh, pregnant woman being accosted here!’ I shouted, garnering glances as I fought her off me, but nobody in the café paid much mind. Typical. Pregnant women are pretty much invisible to the human eye.

There was a selfie of Marnie and Tim together on her screen saver. She was smiling and he was hugging her from behind – like a chokehold. Hmm, attractive in an Aryan kind of way but a bit too much pulse for my liking.

I checked her call log and messages and once my suspicions were confirmed, I handed the phone back. She was hot in both cheeks, grabbing her jacket off her chair and flinging it on.

‘Fifty-seven calls. In two days. And you live with the guy.’

She wouldn’t look at me. She threw her handbag strap over her shoulder and shuffled out of the banquette.

‘One hundred and seventy-six messages in a week,’ I called after her as she waddled back through café, as fast as she could.

She snapped her head around. ‘So what? He’s protective. I told you.’

We got to the top of the escalators. ‘Just cos you’re married, doesn’t mean he owns you. That kind of thinking went out with McBusted.’

‘He’s not your grandad, okay? He’s not that Priory Gardens guy either. He’s ex-army so he likes things just so and he fusses a bit, that’s all. I get him. I get why he’s like it and it’s okay. I love him. End of.’

‘No not “end of”. Did he make you stop dancing?’ She didn’t answer. ‘Does he hurt you?’

I tried to think of something women’s refugey and supportive to say, but nothing came. All I saw was her eyes not daring to water and the only way I could think of helping was to go straight round to that plastics factory and anally violate the gutless little piss-tray with some sort of pointy thing.

She started down the escalator.

‘Uh, what am I supposed to do, get the bus home?’ I called out.

She waited at the bottom. I went down and stood beside her in silence.

‘He doesn’t hurt me. I promise. He needs me. But I don’t want to talk about this anymore, okay? I’m asking you, please.’ Her voice dropped to a whisper. ‘Just be a friend today.’

For some reason that word ‘friend’ changed my outlook. I didn’t want her to leave and I didn’t want her anger. I wanted to stay being her friend.

‘Let’s go somewhere else, yeah? How about the museum?’

‘Why the museum?’

‘I used to go there all the time when I was a kid with my friend. Shall we do that?’ She checked her phone. ‘Oh sorry. What time does Goebbels want you back in the Stalag?’

She laughed at that. I didn’t think she would. ‘Six.’

‘Bags of time,’ I said. ‘Come on. It’s not far.’

We drove across town without another word about He Who Must Not Be Named and I gave Marnie a potted tour of Bristol and the harbour side. We took a slow walk up Park Street, tried on hats in a hat shop, shoes in a shoe shop and finally we went to my favourite place: the museum. I showed her all the best bits first – the gift shop, the Egyptian mummies, the rocks and gemstones, the amethyst the size of my head and the stalactite that looked like a willy. Then the stuffed animals gathering dust in their enormous glass cases – The Dead Zoo, as me and Joe called it. I could smell the Dead Zoo before we got to it – musty and pungent with age – and I was drawn to it like a moth. We found Alfred the gorilla, arguably Bristol’s most famous son.

‘Me and Joe used to imagine we were in the jungle and these were all our animals,’ I told her. ‘We lived in the gypsy caravan and at night, the mummies would come alive and we had to hide in case they got us. Alfred would roar and beat his chest and all the mummies would run away. This is Alfred. You have to say Hi when you come here. It’s like a Bristol law.’

‘Hello Alfred,’ she said, waving at him. ‘Who’s Joe?’

‘Joe Leech. He was my best friend when I was a kid. I only knew him for a couple of summers. He was killed. Got knocked down.’

‘Oh that’s awful. I’m sorry.’

‘Apparently when he was in the zoo, Alfred used to throw poo at people and piss on them as they passed underneath his cage. And he hated men with beards. I don’t like men with beards either. Don’t trust them.’

Marnie laughed.

‘Does Tim have a beard at the moment?’

She thinned her eyes. ‘No he doesn’t.’

‘Just checking. We used to spend hours up here, me and Joe.’

‘Smells a bit strange. Some of them look so sad.’

‘Yeah but look at the ones who are grinning. They look insane.’

‘True.’

‘Don’t you find it fascinating? I find death fascinating.’

‘No,’ she said. ‘I find it quite creepy actually.’ She moved around the glass cases with caution as though any moment the ocelot or Sumatran tiger or glassy-eyed rhino might crash through the glass and flatten her.

‘There’s a dodo somewhere,’ I said. ‘That was Joe’s favourite.’

‘You look genuinely happy to be here,’ she remarked.

‘Yeah, I think I am. I was happy as a kid. Before Priory Gardens. And when I was with Joe. And Craig. Not so much since.’

This remark seemed to trouble Marnie all afternoon. She brought it up several times as we were wandering round but put it down to the whole Craig-being-in-prison and not-having-a-baby-daddy-around thing.

After the gift shop – where Marnie again noted several things she liked but wouldn’t buy – we went over the road to Rocotillos where me and Joe Leech ate short stack pancakes and shakes for breakfast, and dared each other to blow cold cherries at the waiters. We sat on stools overlooking the street outside. Marnie said she wasn’t hungry but I ordered her chocolate brownie freak shake with whipped cream and salted caramel sauce, same as me, and she ate every bite. The sky darkened and rain began spattering the window.

She sucked her straw in ecstasy. ‘Mmm, I’d forgotten what chocolate tastes like. It’s not good for you, too many sweets.’

‘Is Tim afraid you’ll get fat?’

She nodded, seemingly forgetting herself as she chewed the tip of her straw. ‘He’s worried about diabetes, that’s all. He doesn’t think it’s good for me to gain too much fat.’

‘No, I suppose it absorbs the punches too well.’

Marnie rolled her eyes like she’d known me for years and this was something ‘typically Rhee’. ‘Things change after you have a baby. Men can… stray. That’s what I’m most afraid of I guess. I couldn’t handle that. My dad cheated on my mum and it broke her heart and mine.’

‘So if he cheated on you, you might find the strength to leave him?’ A little thought owl flew into my mind.

‘Don’t even think about it,’ she said firmly. ‘I’d never forgive you.’

My thought owl flew out again. ‘I’d like to meet Tim.’

‘Why?’

I spooned some cream from my shake. ‘Just to be sociable.’

‘You’re not sociable though,’ she chuckled.

‘I’m out with you, aren’t I? What more do you want?’

She looked out of the window but I knew she didn’t want to look at me. ‘He’ll be coming to Pin’s cheese and wine. And she’s planning a big fireworks party in November for her birthday as well. No expense spared.’

‘Oh Christ,’ I groaned. ‘She’s not going to invite me to those, is she?’

‘Of course she is,’ said Marnie. ‘You’re one of the gang now.’

‘Ugh. I need that like a hole in the womb.’

‘Pin’s house is amazing. They’re millionaires.’

‘Whoopee shit.’ I blew a cold cherry at a passing waitress. It missed.

Outside it was raining hard. People rushed past the window with briefcases on their heads and newspapers folded over like makeshift hats. ‘What do you want to talk about then?’ I asked. ‘You choose. Ask me anything. Any question you’ve always wanted the answer to. Priory Gardens, Craig, you name it. Open season.’

Marnie stared at the window and took two bites before answering. ‘If you counted every raindrop as it fell, how many raindrops would there be?’