Полная версия

Once Is Enough

We had one or two visitors in our new berth, and one of them was a tall elderly man, in a town suit, and a black hat, but one glance was enough to see that he was no city man. He was a sailor, and he knew a great deal not only of sail but also of the Southern Ocean. ‘Well,’ he said when he left, ‘Good luck to you. I think you’re going to need all of it, and I must say that I’d like to see another 7 feet off those masts.’

We thought that all small ship passages, at any rate long passages, had an element of luck about them—so is there about most things that are worth doing. But if we had thought that it was just a question of luck whether we would arrive or not, we wouldn’t have attempted the passage. We were most certainly not in search of sensation, and we believed that we had a ship and a crew that were capable of making the passage under normal conditions. We knew of course that we might meet with bad luck in all kinds of ways, but as long as we were prepared, as far as was possible, for anything that might turn up, there seemed to be no reason why we should not overcome it.

‘What on earth do you want a year’s supply of stores on board for?’ someone asked Beryl.

‘Well,’ she said, ‘there is always the possibility that we might get dismasted, and then heaven knows where we might end up, and anyway the passage would take much longer than we had expected. We could probably make do for water, but I like to be sure that we have all the food we need.’

Australia was a good place to buy all kinds of tinned food, and besides tinned food we had potatoes, onions, and two sides of bacon, as well as plenty of oranges; and after the oranges were finished, we had tinned orange-juice or grapefruit-juice in almost unlimited quantity.

Although there is plenty of stowage space on Tzu Hang, we were so well stocked that Beryl began to think of creating more by getting rid of Blue Bear. Blue Bear had become a ship’s mascot, and John and I wouldn’t hear of it. He had been given to Clio when we first left England. He was a blue teddy bear, inappropriate and too big, but no artifice of ours could persuade Clio to part with him. When we were crossing the Bay of Biscay, and beating down against a south-westerly wind, with Tzu Hang close-hauled and sailing herself, Blue Bear, in oilskin and sou’wester, was lashed to the wheel. Through the doghouse windows we had seen a steamer come away from her course and steam up alongside to investigate. The captain came out of his cabin without his jacket, dressed in trousers and braces, to peer through his glasses, and others of the crew lined the rail. Blue Bear was obviously the centre of all interest, and when they drew away they seemed still to be discussing the composition of the crew.

He had sailed with us on every trip, lolling in one of the bunks, often with the cat and dog keeping him company, and now I found a more austere berth for him on the shelf in the forepeak, where he could still keep his eye on what went on.

There was one major difficulty to overcome before we left, and that was to get John to have his impacted wisdom tooth pulled out.

‘Not likely,’ said John. ‘He said he’d have to dig it out, and anyway it’s not hurting.’

‘But you must have it done, it might blow up on the trip.’

‘Not me. I don’t want to have a tooth dug.’

‘But John,’ Beryl said, ‘you sail all the way from Canada in that tiny boat, and now you won’t have a tooth out. I do believe you’re frightened.’

‘Too true,’ he said, with his usual disarming frankness, but in the end he agreed. After all there was a very pretty girl there to hold his hand. When we came back from a visit to Tasmania it was out, and John had a swollen jaw and a smug look.

Next morning I went to the Customs Office to arrange for clearance. I got into the lift and pressed the button for the appropriate floor. The lift started up and then came to a shuddering halt half way up. I tried to peer through the grille, but I was right between two floors. I thought that if I waited for long enough someone was sure to want the lift and I should be discovered without the indignity of bawling for help. After about ten minutes I heard an angry voice from below shouting, ‘You up there: what are you doing in the lift?’

‘I’m stuck!’ I shouted indignantly.

‘Well, stand in the middle, then.’

I stood in the middle, and the lift began to climb creakily upwards again. A few minutes later I was shaking hands with the Customs Officer, with my clearance in my pocket for the following day.

‘I’ll let the Customs launch know,’ he said, ‘and they’ll meet you at the mouth of the river and give you a check up as you go. I remember the last chap we cleared for Montevideo was that Irishman, Conor O’Brien, some thirty years ago. He had a ship with a funny name.’

‘Saoirse.’

‘Yes, that’s right. He had a beard and a yachting cap. He was a rum chap, but he was a real sailor,’ and he looked at me doubtfully.

I hoped that I might be half as good, but I knew that he couldn’t have had so good a crew.

CHAPTER TWO

FALSE START

A TUG whistled down the river. Beryl sat up in her bunk as if this was the signal that she had been waiting for. She pulled a jersey over her pyjamas and went aft to the galley. I lay in my bunk. I thought that it would be the last time for days and days that I would lie in my bunk with the ship still.

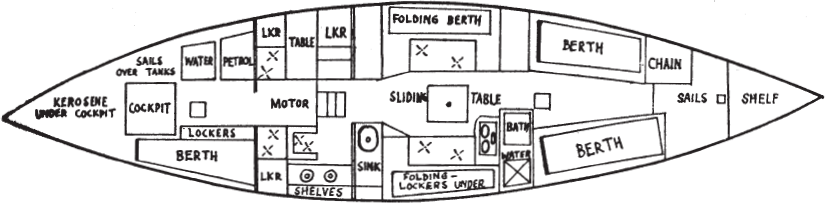

John was also in his bunk, a quarter-berth that he had made in New Zealand, aft of the galley and doghouse. He had separated it from the rest of the cramped stowage space below the bridge-deck by a plywood partition running fore-and-aft from the cockpit to the bulkhead on the starboard side. Whenever I tried to get into this berth through an oval hole cut in the partition, in order to get to the stowage space aft of the cockpit, I stuck, either with my head in and my stern out, or my stern in and my head out. John used to go in stern first like a wart-hog going into its burrow. Although he was bigger than I, but not taller, he did everything with an effortless grace, and could even get in and out of his berth with no apparent difficulty. It was snug inside and removed from the rest of the ship. It was his quarter—a small piece of privacy which was never invaded.

I knew exactly what was going on in the galley, without looking aft through the ship to where Beryl was sitting in the cook’s seat behind the dresser and sink and beside the stoves: an oil stove and a primus on gimbals, so that they swung either way and remained steady when the ship pitched and rolled. There was an occasional rattle and clink, well-known noises which I could interpret from days of practice at sea, and then came the sudden welcome hiss of the primus burner and the sound of the primus pump. Soon the porridge was on the stove and Beryl came back to the forecabin to finish her dressing. I put on some clothes and went on deck by way of the forehatch.

It was a sparkling summer day, with a light wind blowing up the Yarra River. A little further down, a big cargo ship was docking. The tug, whose whistle had stirred us to movement, was pushing the steamer’s stern in to the wharf. ‘Today is the day,’ I thought, ‘today is the day.’ And then I remembered that Pwe had not yet returned from her night out. I called her, and she answered from the shrubs by the railing. She came trotting out, explaining as only a Siamese can, about being caught out by the daylight, and about the sparrows being so wary. When she got near to the edge of the wharf, she lay down and rolled, waiting for me to come and get her. I stepped on shore and picked her up, and Beryl called ‘Breakfast’ from the hatch.

That wonderful call to breakfast! I do not know whether it is because of its association with porridge and bacon and eggs, but her voice always sounds as young and exciting as ever it did, and the day seemed young and exciting too. It was an exciting day. It was the twenty-second of December, and we were starting off to England.

Our first job after breakfast was to move round to a water point on the main wharf, where we could top up our tanks. If a hose was not available we used 2-gallon plastic bottles. When we bought Tzu Hang, she had only one tank of 20 gallons, so that we had to fit in other tanks where we could. We put one under each bunk in the forecabin, one in the bathroom, one under the existing tank in the galley, and one in the after compartment, opposite John’s berth. It was the best we could do, and it is not a bad principle to have water well divided. It is easier to check consumption, and all is not lost if a tap is knocked on and not noticed.

We carried about 150 gallons of water in these six tanks. We found that half a gallon a day per person, at sea, was a fair allowance. When we washed, we washed in salt water, and whenever possible we used salt water for cooking. Water was never rationed, but we did not waste it, and now we reckoned that we had at least a three-months’ supply, and a little extra for washing if necessary.

Before we had set out on our first trip I had had a letter from Kevin O’Riordan, who had sailed across the Atlantic with Humphrey Barton in Vertue XXXV. He wrote, ‘You will be perfectly all right provided that you have a buoyant boat, plenty of water, and don’t mind being alone for weeks and weeks.’ It seemed that all three conditions were fulfilled.

The last days before leaving on a long trip are always a rush. The whole crew spin like dancing dervishes, the list of things undone seems to grow longer instead of shorter, and everything whirls faster and faster to the climax, the moment between preparation and departure, between planning and putting into effect, the climax when a starter button is pressed, and the engine starts … or doesn’t.

I always hate this moment as I’m a bad engineer, and I feel that some imp of fortune is going to decide whether we shall be permitted to cast off, or whether we shall become the harrowed and querulous prey of a thousand mechanical doubts and remain tied to the wharf that we want to leave. ‘Please, engine, please start,’ I beg of it in private, but on this occasion everything went well.

Beryl jumped into the cockpit and took the wheel. She put the engine astern, and we began to back out from the dock into the Yarra River. As the stream caught our deep keel it swung the stern round until we were facing upstream, Beryl then put the engine ahead and we moved slowly across to the water point on the wharf. John had walked across to catch our lines. Ever since he had joined us in New Zealand, he had taken every opportunity to work on Tzu Hang, making some improvement or other. Now, as she came out into the stream, he was able to look at her from a distance for perhaps the last time for many a long day. She looked fit for the sea in every way. The boom gallows could be improved; perhaps he would be able to fix it before he left the ship.

As soon as we had made fast, we began topping up the tank in use with the plastic bottles. Last of all, we filled the four bottles and stowed them below. Pwe was eager for a last run ashore, but the distance from the deck to the top of the wharf was too much for her. A tall young girl, about ten years old, with a mop of dark hair, was standing on the wharf with her father, looking down at the yacht. When she saw the cat, her eyes, which were as blue as the cat’s, went round with wonder. She looked as if, more than anything else in the world, she wanted to stroke it. I climbed on to the wharf with Pwe, and held her out to her. She was too shy to speak. She stroked the cat’s dark head, and longed after her when I handed her down again to Beryl.

It was time to be moving now. Beryl was at the wheel, John was ready to cast off the bowline, and the young girl’s father was hoping to be asked to cast off the stern-line.

‘All right, let go,’ I called to John, and ‘Would you mind casting off?’ to the eager father.

John jumped on board and, helped by the stream, Tzu Hang swung out into the river and pointed her head for the sea.

Half way down to the river mouth we were met by the Customs launch. ‘Thought that we’d come up and give you a tow,’ they shouted as they came alongside. One of the Customs Officers came on board, and they passed us a towline.

‘What can you do?’

‘Eight knots,’ we answered, knowing something of Australian enthusiasm. In no time Tzu Hang’s bow was climbing out of the water and she was foaming along, doing at least twelve knots behind the powerful launch. Every now and then she would take a sheer and, before Beryl could correct it, the towrope would tighten across the bobstay, setting the bowsprit shrouds twanging. We were soon out of the river and opposite Williamstown. We had our clearance, and the launch came alongside again to take off the Customs Officer.

‘Goodbye,’ they shouted. ‘Good luck, come again.’

The launch curved away as they waved, ensign fluttering and brass-work shining. They seemed so typical of the Australians that we had met, friendly, efficient, and enthusiastic.

We set all sail and, close-hauled, went slowly down across the bay in the sunshine. The land and houses disappeared, the hills at the southern end of the bay were lost in haze. Here and there a few trees appeared, like a mirage on the horizon. For the rest of the day we sailed slowly across the big land-locked bay, until evening brought the lights winking out on the shore, and the channel buoys began to flash the way to the Heads. We dropped anchor off Dromana, waiting as so many sailing ships had done before, for the ebb tide to take us down early next morning to the Heads, so that we could pass through them at slack water.

Port Phillip Heads are a narrow gap, only a few hundred yards across, through which all the vast area of Port Phillip Bay pours out its waters during the ebb tide, and through which the sea comes boiling and bubbling on the flood. If the wind is against the ebb, the passage can be very dangerous. It was slack water at the Heads at ten-thirty so that we didn’t have to get up early. That night Tzu Hang swung quietly to her anchor, as motionless as if she was still at the wharf in the Yarra River. The tide chattered busily along her planking during the night, first out to sea, and then into the bay, and then out to sea again. And in the last hour of this tide we hauled in our anchor, started the engine, and motored down the misty channel.

The buoys came up out of the murk one after the other, and we checked their numbers against the chart. The mist cleared and we could see the Heads, and as soon as we were on the right bearing we turned to run out. As we passed the signal station at Point Lonsdale we saw the signal for the tides change from the last quarter to the first quarter; it was exactly slack water and there was no ripple on the surface. On the port hand there was the black and red rusting hull of a steamer wrecked on the shoals, and ahead the sails of two yachts. As soon as we were through we stopped the engine and got up sail ourselves, but the wind was very light from the south and we made very slow progress on the port tack.

By the evening we were becalmed and the mainsail was flapping about as we rolled. We handed all sail. About midnight there was a slight breeze again and I hoisted the main. As I did so, the boom dropped out of the gooseneck, and I found that the bronze fitting on the boom had fractured. The gooseneck was frozen with rust and the bronze fitting had been bending, but, as we were close-hauled, we had not noticed it. Now it had broken and, as we were still within easy reach of a port, it was just as well to have it repaired. We should have checked and oiled the goosenecks before leaving. We turned in for the rest of the night, and early next morning set off for Westernport, a few miles down the coast and up a long arm of the sea.

The wind strengthened and we ran up the long channel against the tide, followed by the two yachts that we had seen leave the Heads before us. We tied up to a wharf at a small harbour called Cowes, leaving an anchor out to hold us off the wharf if the wind shifted. This caused great distress to the captain of a steam ferry which brought holiday-makers over to Cowes. Although he hadn’t asked me to move it, he came up to me complaining angrily, as if I had already refused. I was only too anxious to move it when I found that there was a chance of the ferry fouling the line. We walked up through the village, a steep little hill, and there was a cold fresh wind blowing, which made the cotton frocks and the shirtsleeves of the Christmas visitors look out of season. At the top we found a garage and were able to get the boom fitting repaired, but it was late when we got back to the ship and, as the wind was blowing strongly down the narrow channel, we decided to leave on the tide next morning.

We had just started dinner, when there was a loud crash against the bow, and something started to scrape down the side of the ship.

‘Heavens, what on earth’s that?’ said Beryl.

‘Sounds as if we’ve got a visitor.’

We all scrambled up on deck as quickly as possible, including Pwe, who hates being left absolutely alone below. One of the yachts which had been tied up ahead of us had broken its stern-line and had swung round, putting its bowsprit through the pilings of the wharf, and breaking it off. We fended her off Tzu Hang, and while I jumped on board to look for another line, John climbed up on the wharf to get her bowline. He towed her back to her position, and we made her fast again with the best of a bad lot of line that I found in the cockpit. The wind was really blowing up and it looked as if we might have to move away from the wharf.

We settled down to dinner again, but it was a dreary Christmas Eve without Clio. Last Christmas there had been an inappropriate tree in the boat and decorations and presents and all the litter of Christmas. And now, not only were we missing the person who had made it all necessary, but we ought to have been at sea and not stuck in Westernport. John had an innate understanding of people’s feelings and the good sense not to intrude upon them. He was neither unnaturally hearty nor over-sympathetic. In fact he was just himself. When Beryl offered him some brandy butter to go with his plum pudding, he said rather gloomily, ‘Brandy butter, made with margarine and rum.’ We all began to feel better.

Before the plum pudding was finished, there was another bump against the bow, and we found that the same yacht had joined us again. The owners arrived while we were disentangling her. They hoisted the mainsail and sailed her round into the sheltered water behind the angle of the pier, where they anchored. An hour later Tzu Hang began to bump against the pilings. It was raining and as black as a night can be. The lights shone on a wet deserted wharf, and the sounds of a dance band came across from the hotel.

We untangled ourselves from the network of lines and hawsers, and pushed off into the night, groping for a nine-fathom patch, with Beryl trying to take the bearings of the wharf lights on the compass and John swinging the lead-line. We could not go where the other yacht had gone as there was insufficient water, and in the end we dropped the anchor in twelve fathoms, with forty fathoms of chain, and hoped that we’d be able to get it up again in the morning.

All Christmas Day the wind blew strongly down the channel, and we stayed at anchor, very busy making everything still more secure for the journey ahead, and it was not until Boxing Day morning that we set about getting the anchor in again, in time to sail with the tide. For some time we couldn’t break it out, but at last it came away, covered with thick blue clay. We unshackled it and let the chain go into the chain locker, after marking the end, and we lashed the anchor down, and fixed a ventilator over the chain navel. We expected to be well battened down for much of the way, and hoped that the ventilator would give us sufficient fresh air in the forecabin.

Meanwhile we were motoring up the channel, and in spite of a very rough short sea, with the wind against the tide, we were making good progress. By midday we were passing the lighthouse at the entrance to the loch, and we could see little coloured specks of holiday visitors all along the cliff-top. We kept under power until we were far enough out to clear Seal Rocks on the port tack, on our course for the south.

‘I wonder how many rocks there are in the world called “Seal Rocks”?’ said John.

‘Let’s hope the next “Seal Rocks” will be called “Los Lobos”,’ said Beryl, ‘that’s what they call them in South America.’

We went up and down, up and down, crunch and splash, crunch and splash, but gradually we drew clear, and then we switched off the engine. We would test it from time to time, but we would use it next, or so we hoped, to enter Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands, 6,700 sea-miles away. Up went the staysail, and Tzu Hang began to sail. Next the main and then the storm-jib, and we lay over and hissed away to the south. We cleared Seal Rocks easily, and Tzu Hang felt like a horse held in at the beginning of a long race; she seemed to snatch at her bridle, the foam flecks flying; I felt her great reserve of strength and power; she flung the wave tops behind her like fences. ‘Let us go, let us go,’ she seemed to say. Who could doubt that she would bring us safely home?

Beryl was at the wheel. She was wearing a yellow oilskin jumper with a hood attached and yellow oilskin trousers, and they were wet and shining with spray and from a brief shower that had passed over us; a wisp of wet hair escaped from under the hood and clung to her cheek, which was flushed with the wind, and she was radiant with delight at being off on the long trip at last. From now on she would not worry or think very much about her daughter. For the time being all her energies and thoughts would be directed to the ship and the two of us. Now that we were off she could neither write to nor hear from England, nor could she bring any further influence to bear on Clio’s future, but she knew that she, more than anyone, could make this trip a success and she was going to do it.

John and I were both wearing green plastic oilskins and trousers of a strong material which we had found in New Zealand. They were called tractor suits and had stainless steel press buttons which never failed us. They had a short cape just to give a double thickness over the shoulders, but when on watch at night and in the higher latitudes, we usually wore the coats over our yellow oilskin jumpers, so that we had the advantage of the oilskin hood. John almost invariably wore a British Columbian Indian sweater, knitted from raw wool, and a knitted hat of the same material, with a round bobble on top; and I wore a red knitted sock. Both of them could be pulled down over the ears, and were often worn like this, in spite of the moronic look that they gave us. For many days to come we were not going to think very seriously about looks.

After setting the mainsail and storm-jib, John and I came aft to where Beryl had already set the mizzen, and we swigged it up a few inches. Then John took the wheel, for it was his watch. Beryl went down below, to lie in her bunk and get some rest before tea. I went below also to check the course on the chart and make the entries in the log, and from the cockpit came a great burst of song: ‘Stand up and fight boy, when you hear the bell,’ the words came wind-torn into the cabin. We were going to hear a lot about that bell when the going was good.