Полная версия

Night of Error

DESMOND BAGLEY

Night of Error

COPYRIGHT

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Collins 1984

Copyright © Brockhurst Publications 1984

Cover layout design Richard Augustus © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Desmond Bagley asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780008211370

Ebook Edition © August 2017 ISBN 9780008211387

Version:2017-07-05

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Night of Error

Dedication

Preface

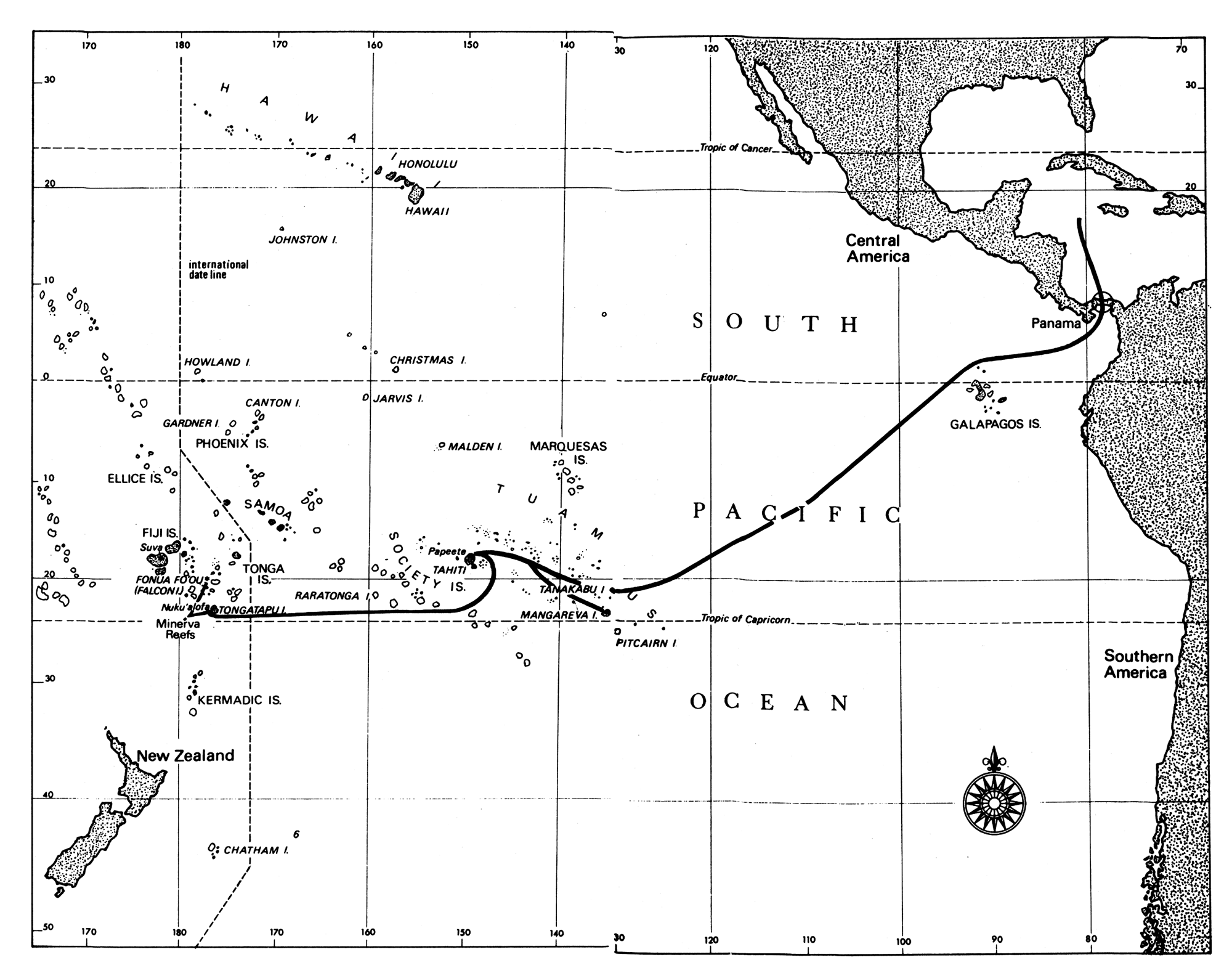

Map

Epigraph

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

DEDICATION

For STAN HURST, at last, with affection

PREFACE

The Pacific Islands Pilot, Vol. II, published by the Hydrographer of the Navy, has this to say about the island of Fonua Fo’ou, almost at the end of a long and detailed history:

In 1963, HMNZFA Tui reported a hard grey rock, with a depth of 6 feet over it, on which the sea breaks, and general depths of 36 feet extending for 2 miles northwards and 1 1/2 miles westward of the rock, in the position of the bank. The eastern side is steep-to. In the vicinity of the rock, there was much discoloured water caused by sulphurous gas bubbles rising to the surface. On the bank, the bottom was clearly visible, and consisted of fine black cellar lava, like volcanic cinder, with patches of white sand and rock. Numerous sperm whales were seen in the vicinity.

But that edition was not published until 1969.

This story began in 1962.

MAP

EPIGRAPH

And when with grief you see your brother stray, Or in a night of error lose his way, Direct his wandering and restore the day. To guide his steps afford your kindest aid, And gently pity whom you can’t persuade: Leave to avenging Heaven his stubborn will, For, O, remember, he’s your brother still.

JONATHAN SWIFT

ONE

I heard of the way my brother died on a wet and gloomy afternoon in London. The sky was overcast and weeping and it became dark early that day, much earlier than usual. I couldn’t see the figures I was checking, so I turned on the desk light and got up to close the curtains.

I stood for a moment watching the rain leak from the plane trees on the Embankment, then looked over the mistshrouded Thames. I shivered slightly, wishing I could get out of this grey city and back to sea under tropic skies. I drew the curtain decisively, closing out the gloom.

The telephone rang.

It was Helen, my brother’s widow, and she sounded hysterical. ‘Mike, there’s a man here – Mr Kane – who was with Mark when he died. I think you’d better see him.’ Her voice broke. ‘I can’t take it, Mike.’

‘All right, Helen; shoot him over. I’ll be here until five-thirty – can he make it before then?’

There was a pause and an indistinct murmur, then Helen said, ‘Yes, he’ll be at the Institute before then. Thanks, Mike. Oh, and there’s a slip from British Airways – something has come from Tahiti; I think it must be Mark’s things. I posted it to you this morning – will you look after it for me? I don’t think I could bear to.’

‘I’ll do that,’ I said. ‘I’ll look after everything.’

She rang off and I put down the receiver slowly and leaned back in my chair. Helen seemed distraught about Mark and I wondered what this man Kane had told her. All I knew was that Mark had died somewhere in the Islands near Tahiti; the British Consul there had wrapped it all up and the Foreign Office had got in touch with Helen as next of kin. She never said so but it must have been a relief – her marriage had caused her nothing but misery.

She should never have married him in the first place. I had tried to warn her, but it’s a bit difficult telling one’s prospective sister-in-law about the iniquities of one’s own brother, and I’d never got it across. Still, she must have loved him despite everything, judging by the way she was behaving; but then, Mark had a way with his women.

One thing was certain – Mark’s death wouldn’t affect me a scrap. I had long ago taken his measure and had steered clear of him and all his doings, all the devious and calculating cold-blooded plans which had only one end in view – the glorification of Mark Trevelyan.

I put him out of my mind, adjusted the desk lamp and got down to my figures again. People think of scientists – especially oceanographers – as being constantly in the field making esoteric discoveries. They never think of the office work entailed – and if I didn’t get clear of this routine work I’d never get back to sea. I thought that if I really buckled down to it another day would see it through, and then I would have a month’s leave, if I could consider writing a paper for the journals as constituting leave. But even that would not take up the whole month.

At a quarter to six I packed it in for the day and Kane had still not shown up. I was just putting on my overcoat when there was a knock on the door and when I opened it a man said, ‘Mr Trevelyan?’

Kane was a tall, haggard man of about forty, dressed in rough seaman’s clothing and wearing a battered peaked cap. He seemed subdued and a little in awe of his surroundings. As we shook hands I could feel the callouses and thought that perhaps he was a sailing man – steam seamen don’t have much occasion to do that kind of hand work.

I said, ‘I’m sorry to have dragged you across London on a day like this, Mr Kane.’

‘That’s all right,’ he said in a raw Australian accent. ‘I was coming up this way.’

I sized him up. ‘I was just going out. What about a drink?’

He smiled. ‘That ‘ud be fine. I like your English beer.’

We went to a nearby pub and I took him into the public bar and ordered a couple of beers. He sank half a pint and gasped luxuriously. ‘This is good beer,’ he said. ‘Not as good as Swan, but good all the same. You know Swan beer?’

‘I’ve heard of it,’ I said. ‘I’ve never had any. Australian, isn’t it?’

‘Yair; the best beer in the world.’

To an Australian all things Australian are the best. ‘Would I be correct if I said you’d done your time in sail?’ I said.

He laughed. ‘Too right you would. How do you know?’

‘I’ve sailed myself; I suppose it shows somehow.’

‘Then I won’t have to explain too much detail when I tell you about your brother. I suppose you want to know the whole story? I didn’t tell Mrs Trevelyan all of it, you know – some of it’s pretty grim.’

‘I’d better know everything.’

Kane finished his beer and cocked an eye at me. ‘Another?’

‘Not for me just yet. You go ahead.’

He ordered another beer and said, ‘Well, we were sailing in the Society Islands – my partner and me – we’ve got a schooner and we do a bit of trading and pick up copra and maybe a few pearls. We were in the Tuamotus – the locals call them the Paumotus, but they’re the Tuamotus on the charts. They’re east of …’

‘I know where they are,’ I interrupted.

‘Okay. Well, we thought there was a chance of picking up a few pearls so we were just cruising round calling on the inhabited islands. Most of ’em aren’t and most of ‘em don’t have names – not names that we can pronounce. Anyway we were passing this one when a canoe came out and hailed us. There was a boy in this canoe – a Polynesian, you know – and Jim talked to him. Jim Hadley’s my partner; he speaks the lingo – I don’t savvy it too good myself.

‘What he said was that there was a white man on the island who was very sick, and so we went ashore to have a look at him.’

‘That was my brother?’

‘Too right, and he was sick; my word yes.’

‘What was wrong with him?’

Kane shrugged. ‘We didn’t know at first but it turned out to be appendicitis. That’s what we found out after we got a doctor to him.’

‘Then there was a doctor?’

‘If you could call him a doctor. He was a drunken old no-hoper who’d been living in the Islands for years. But he said he was a doctor. He wasn’t there though; Jim had to go fifty miles to get him while I stayed with your brother.’

Kane took another pull at his beer. ‘Your brother was alone on this island except for the black boy. There wasn’t no boat, either. He said he was some sort of scientist – something to do with the sea.’

‘An oceanographer.’ Yes, like me an oceanographer. Mark had always felt compelled, driven, to try and beat me whatever the game. And his rules were always his own.

‘Too right. He said he’d been dropped there to do some research and he was due to be picked up any time.’

‘Why didn’t you take him to the doctor instead of bringing the doctor to him?’ I asked.

‘We didn’t think he’d make it,’ said Kane simply. ‘A little ship like ours bounces about a lot, and he was pretty sick.’

‘I see,’ I said. He was painting a rough picture.

‘I did what I could for him,’ said Kane. ‘There wasn’t much I could do though, beyond cleaning him up. We talked a lot about this and that – that was when he asked me to tell his wife.’

‘Surely he didn’t expect you to make a special trip to England?’ I demanded, thinking that even in death it sounded like Mark’s touch.

‘Oh, it was nothing like that,’ said Kane. ‘You see, I was coming to England anyway. I won a bit of money in a sweep and I always wanted to see the old country. Jim, my cobber, said he could carry on alone for a bit, and he dropped me at Panama. I bummed a job on a ship coming to England.’

He smiled ruefully. ‘I won’t be staying here as long as I thought – I dropped a packet in a poker game coming across. I’ll stay until my cash runs out and then I’ll go back to Jim and the schooner.’

I said, ‘What happened when the doctor came?’

‘Oh sure, you want to know about your brother; sorry if I got off track. Well, Jim brought this old no-good back and he operated. He said he had to, it was your brother’s only chance. Pretty rough it was too; the doc’s instruments weren’t any too good. I helped him – Jim hadn’t the stomach for it.’ He fell silent, looking back into the past.

I ordered another couple of beers, but Kane said, ‘I’d like something stronger, if you don’t mind,’ so I changed the order to whisky.

I thought of some drunken oaf of a doctor cutting my brother open with blunt knives on a benighted tropical island. It wasn’t a pretty thought and I think Kane saw the horror of it too, the way he gulped his whisky. It was worse for him – he had been there.

‘So he died,’ I said.

‘Not right away. He seemed okay after the operation, then he got worse. The doc said it was per … peri …’

‘Peritonitis?’

‘That’s it. I remember it sounded like peri-peri sauce – like having something hot in your guts. He got a fever and went delirious; then he went unconscious and died two days after the operation.’

He looked into his glass. ‘We buried him at sea. It was stinking hot and we couldn’t carry the body anywhere – we hadn’t any ice. We sewed him up in canvas and put him over the side. The doctor said he’d see to all the details – I mean, it wasn’t any use for Jim and me to go all the way to Papeete – the doc knew all we knew.’

‘You told the doctor about Mark’s wife – her address and so on?’

Kane nodded. ‘Mrs Trevelyan said she’d only just heard about it – that’s the Islands postal service for you. You know, he never gave us nothing for her, no personal stuff I mean. We wondered about that. But she said some gear of his is on the way – that right?’

‘It might be that,’ I said. ‘There’s something at Heathrow now. I’ll probably pick it up tomorrow. When did Mark die, by the way?’

He reflected. ‘Must have been about four months ago. You don’t go much for dates and calendars when you’re cruising the Islands, not unless you’re navigating and looking up the almanack all the time, and Jim’s the expert on that. I reckon it was about the beginning of May. Jim dropped me at Panama in July and I had to wait a bit to get a ship across here.’

‘Do you remember the doctor’s name? Or where he came from?’

Kane frowned. ‘I know he was a Dutchman; his name was Scoot-something. As near as I can remember it might have been Scooter. He runs a hospital on one of the Islands – my word, I can’t remember that either.’

‘It’s of no consequence; if it becomes important I can get it from the death certificate.’ I finished my whisky. ‘The last I heard of Mark he was working with a Swede called Norgaard. You didn’t come across him?’

Kane shook his head. ‘There was only your brother. We didn’t stay around, you know. Not when old Scooter said he’d take care of everything. You think this Norgaard was supposed to pick your brother up when he’d finished his job?’

‘Something like that,’ I said. ‘It’s been very good of you to take the trouble to tell us about Mark’s death.’

He waved my thanks aside. ‘No trouble at all; anyone would have done the same. I didn’t tell Mrs Trevelyan too much, you understand.’

‘I’ll edit it when I tell her,’ I said. ‘Anyway, thanks for looking after him. I wouldn’t like to think he died alone.’

‘Aw, look,’ said Kane, embarrassed. ‘We couldn’t do anything else now, could we?’

I gave him my card. ‘I’d like you to keep in touch,’ I said. ‘Perhaps when you’re ready to go back I can help you with a passage. I have plenty of contacts with the shipping people.’

‘Too right,’ he said. ‘I’ll keep in touch, Mr Trevelyan.’

I said goodbye and left the bar, ducking into the private bar in the same pub. I didn’t think Kane would go in there and I wanted a few quiet thoughts over another drink.

I thought of Mark dying a rather gruesome death on that lonely Pacific atoll. God knows that Mark and I didn’t see eye to eye but I wouldn’t have wished that fate on my worst enemy. And yet there was something odd about the whole story; I wasn’t surprised at him being in the Tuamotus – it was his job to go poking about odd corners of the seven seas as it was mine – but something struck a sour note.

For instance, what had happened to Norgaard? It certainly wasn’t standard operating procedure for a man to be left entirely alone on a job. I wondered what Mark and Norgaard had been doing in the Tuamotus; they had published no papers so perhaps their investigation hadn’t been completed. I made a mental note to ask old Jarvis about it; my boss kept his ear close to the grapevine and knew everything that went on in the profession.

But it wasn’t that which worried me; it was something else, something niggling at the back of my mind that I couldn’t resolve. I chased it around for a bit but nothing happened, so I finished my drink and went home to my flat for a late night session with some figures.

II

The next day I was at the office bright and early and managed to get my work finished just before lunch. I was attacking my neglected correspondence when one of the girls brought in a visitor, and a most welcome one. Geordie Wilkins had been my father’s sergeant in the Commandos during the war and after my father had been killed he took an interest in the sons of the man he had so greatly respected. Mark, typically, had been a little contemptuous of him but I liked Geordie and we got on well together.

He had done well for himself after the war. He foresaw the yachting boom and bought himself a 25-ton cutter which he chartered and in which he gave sailing lessons. Later he gave up tuition and had worked up to a 200-ton brigantine which he chartered to rich Americans mostly, taking them anywhere they wanted to go at an exorbitant price. Whenever he put into England he looked me up, but it had been a while since last I’d seen him.

He came into the office bringing with him a breath of sea air. ‘My God, Mike, but you’re pallid,’ he said. ‘I’ll have to take you back to sea.’

‘Geordie! Where have you sprung from this time?’

‘The Caribbean,’ he said. ‘I brought the old girl over for a refit. I’m in between charters, thank God.’

‘Where are you staying?’

‘With you – if you’ll have me. Esmerelda’s here.’

‘Don’t be an idiot,’ I said happily. ‘You know you’re welcome. We seem to have struck it lucky this time; I have to do a bit of writing which will take a week, and then I’ve got three weeks spare.’

He rubbed his chin. ‘I’m tied up for a week too, but I’m free after that. We’ll push off somewhere.’

‘That’s a great idea,’ I said. ‘I’ve been dying to get away. Wait while I check this post, would you?’

The letter I had just opened was from Helen; it contained a brief letter and the advisory note from British Airways. There was something to be collected from Heathrow which had to clear customs. I looked up at Geordie. ‘Did you know that Mark is dead?’

He looked startled. ‘Dead! When did that happen?’

I told him all about it and he said, ‘A damned sticky end – even for Mark.’ Then he immediately apologized. ‘Sorry – I shouldn’t have said that.’

‘Quit it, Geordie,’ I said irritably. ‘You know how I felt about Mark; there’s no need to be mealy-mouthed with me.’

‘Aye. He was a bit of a bastard, wasn’t he? How’s that wife of his taking it?’

‘About average under the circumstances. She was pretty broken up but I seem to detect an underlying note of relief.’

‘She’s best to remarry and forget him,’ said Geordie bluntly. He shook his head slowly. ‘It beats me what the women saw in Mark. He treated ‘em like dirt and they sat up and begged for more.’

‘Some people have it, some don’t,’ I said.

‘If it means being like Mark I’d rather not have it. Sad to think one can’t find a good word to say for the man.’ He took the paper out of my hand. ‘Got a car I can use? I haven’t been in one for months and I’d like the drive. I’ll get my gear from Esmerelda and go out and pick this stuff up for you.’

I tossed him my car keys. ‘Thanks. It’s the same old wreck – you’ll find it in the car park.’

When he had gone I finished up my paperwork and then went to see the Prof. to pay my respects. Old Jarvis was quite cordial. ‘You’ve done a good job, Mike,’ he said. ‘I’ve looked at your stuff briefly and if your correlations are correct I think we’re on to something.’

‘Thank you.’

He leaned back in his chair and started to fill his pipe. ‘You’ll be writing a paper, of course.’

‘I’ll do that while I’m on leave,’ I said. ‘It won’t be a long one; just a preliminary. There’s still a lot of sea time to put in.’

‘Looking forward to getting back to it, are you?’

‘I’ll be glad to get away.’

He grunted suddenly. ‘For every day you spend at sea you’ll have three in the office digesting the data. And don’t get into a job like mine; it’s all office-work. Steer clear of administration, my boy; don’t get chair-bound.’

‘I won’t,’ I promised and then changed tack. ‘Can you tell me anything about a fellow called Norgaard? I think he’s a Swede working on ocean currents.’

Jarvis looked at me from under bushy eyebrows. ‘Wasn’t he the chap working with your brother when he died?’

‘That’s the man.’

He pondered, then shook his head. ‘I haven’t heard anything of him lately; he certainly hasn’t published. But I’ll make a few enquiries and put you in touch.’

And that was that. I didn’t know why I had taken the trouble to ask the Prof. about Norgaard unless it was still that uneasy itch at the back of my skull, the feeling that something was wrong somewhere. It probably didn’t mean anything anyway, and I put it out of my mind as I walked back to my office.

It was getting late and I was about ready to leave when Geordie returned and heaved a battered, ancient suitcase onto my desk. ‘There it is,’ he said. ‘They made me open it – it was a wee bit difficult without a key, though.’

‘What did you do?’

‘Busted the lock,’ he said cheerfully.

I looked at the case warily. ‘What’s in it?’

‘Not much. Some clothes, a few books and a lot of pebbles. And there’s a letter addressed to Mark’s wife.’ He untied the string holding the case together, skimmed the letter across the desk, and started to haul out the contents – a couple of tropical suits, not very clean; two shirts; three pairs of socks; three textbooks on oceanography – very up-to-date; a couple of notebooks in Mark’s handwriting, and a miscellany of pens, toiletries and small odds and ends.

I looked at the letter, addressed to Helen in a neat cursive hand. ‘I’d better open this,’ I said. ‘We don’t know what’s in it and I don’t want Helen to get too much of a shock.’

Geordie nodded and I slit the envelope. The letter was short and rather abrupt:

Dear Mrs Trevelyan,

I am sorry to tell you that your husband, Mark, is dead, although you may know this already by the time you get this. Mark was a good friend to me and left some of his things in my care. I am sending them all to you as I know you would like to have them.

Sincerely,

P. Nelson

I said, ‘I thought this would be official but it’s not.’

Geordie scanned the short note. ‘Do you know this chap, Nelson?’

‘Never heard of him.’

Geordie put the letter on the desk and tipped up the suitcase. ‘Then there are these.’ A dozen or so potato-like objects rolled onto the desk. Some of them rolled further and thumped onto the carpet, and Geordie stooped and picked them up. ‘You’ll probably make more sense of these than I can.’

I turned one in my fingers. ‘Manganese nodules,’ I said. ‘Very common in the Pacific.’

‘Are they valuable?’