Полная версия

Going Home

What was she doing? Why was she in there? I turned to go upstairs, and Mike was standing behind me. I jumped, and heard rustling in the study. ‘What are you doing there?’ he asked. ‘You look like you’re in a world of your own.’

‘N-nothing,’ I stammered. ‘Is Tom in there?’ I gestured towards the study.

His eyes flicked to the door. ‘No, that’s Rosalie. Hey, did you find the Sellotape? We were looking for some earlier and I’ve got one last present to wrap. Ah! Hello, gorgeous, any luck?’

‘Yes, here it is!’ said Rosalie, emerging from the study, holding a dispenser. ‘Hey, Lizzy, how are you?’ She slid an arm round Mike. ‘Shall I run upstairs and do that last one?’

I couldn’t tell if she’d worked out I’d seen her. Or if Mike knew I’d seen her, or if he even knew what she was doing, going through Dad’s stuff.

‘A wife and a present-wrapper, rolled into one. What more could a chap ask for?’ Mike dropped a kiss on her shoulder.

‘I’m going upstairs to get Tom,’ I announced in a loud, peculiarly am-dram way. ‘See you later.’ I stomped upstairs thinking the world was going mad.

On the landing I paused to look out of the leaded window across the valley. What was David doing now? Was he with Alice and Miles, having a drink and opening presents? Was he pacing the floors, dashing tears from his eyes because of his stupid behaviour and thwarted love for me, like the Marquis of Vidal in Devil’s Cub?

Ha. I gave a mirthless laugh, like a world-weary torch singer. I knocked on Tom’s door. There was no answer, so I opened it slowly and looked in. Tom was lying on his bed, staring into space. ‘Tom, darling,’ I said, and sat down next to him. ‘What’s wrong?’

‘Go away,’ he said dully. The old iron bedstead creaked beneath us. ‘I don’t feel well.’

‘Is it your dad?’ I said, putting my arm round his bony shoulders.

‘What do you mean?’ he said, shrugging me off.

‘Well, it’s Christmas Day and all that. It must be sad.’

Tom turned back to look at me without expression. ‘I don’t want to talk about it.’

‘But…’ I didn’t want to sound stupid. ‘We visit his grave every year, why are you so upset this time?’

‘I just am, that’s all. It’s different this year.’

‘But why?’

‘I’ve been thinking about something you said in the car yesterday. And about Mike and stuff.’

‘Oh, God, what?’ I said, alarmed that something I’d said and couldn’t remember should send Tom into a decline.

‘Nothing, just about us all in general. It’s not a big deal, and it’s none of your business. Go away and stop being so nosy.’

Downstairs I heard Mum shout, ‘Change of plan! Lunch is ready! Presents afterwards!’ followed by the dull clang of the bell. I didn’t know what to say. Tom is more than a cousin to me: he’s like my brother – but I often feel I don’t know him very well. I went to his birthday party last year, in a wine bar in the City, and I knew lots of his friends but he seemed…different. More relaxed, happier. And I suppose sometimes the people who know you best are the ones you want to run away from most.

I stroked his arm again. ‘Tom, whatever it is, I want to help. You know that, don’t you?’

There was no answer so I got up and opened the door. Then Tom said, in a muffled voice, ‘I’ll see you downstairs, Lizzy. Thanks.’

‘And the glory, the glory of the Lord…’ boomed the CD player, as I went downstairs. I could hear Dad sharpening the carving knife in time to The Messiah and rushed into the dining room. The table was set, the fire burned in the grate, and the smell of Christmas lunch was drifting through the kitchen door. Mum and Kate were giggling: in a few short hours Gibbo had twisted them round his little finger, and I could see why. If I’d caught him rifling through Dad’s desk I’d have told him to take what he wanted.

One by one we sat down and the dishes came forth from the kitchen. Slices of stuffing, sausage and chestnut, bread sauce, cranberry sauce, Brussels sprouts, and a huge platter of roast potatoes. And finally, with a flourish, in came Mum with the turkey. I sat on my hands to stop myself picking at anything.

Tom appeared at last, a grim expression on his face, and proceeded to down a glass of red wine.

As Dad finally sat down, we raised our glasses and said, ‘Happy Christmas.’

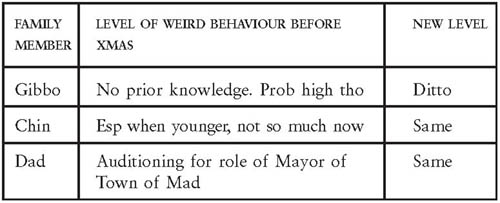

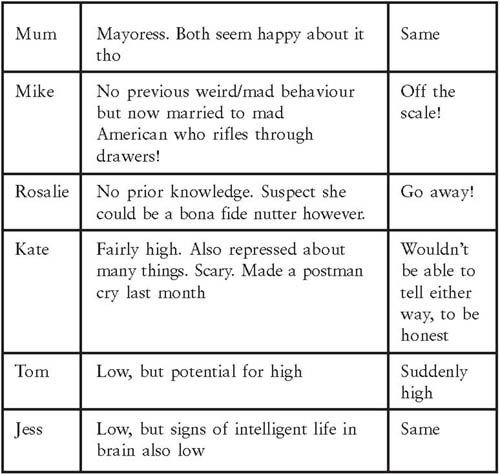

I looked round at all of us and thought what a pickle we were in, even though we appeared to be a normal happy family enjoying Christmas. I wondered what Georgy, Ash and my other friends were doing. Were they as confused by their own family Christmas as I was? Whoever had said that each family was barking insane in its own way was right. Just look at the evidence:

I’m sure our ancestors were all scavenging peasantry because I’ve never known anyone like my family when it comes to attacking a meal with gusto. Silence reigned as we ploughed through the mountains of food in front of us, with only Rosalie making an attempt at conversation.

‘These are beautiful, Suzy,’ she’d say, picking at a crumb of roast potato.

‘Mmm,’ my mother would answer, as her nearest and dearest guzzled, pausing only to open another bottle of wine. conversation broke out. I must say we were rather knocking back the wine but as they say, Christmas comes but once a year, and it is the season to be merry. It was probably nearing teatime but, just as at weddings, where one has nothing to eat for hours and then lunch at 6pm, we’d lost all sense of time.

After the pudding and mince pies, we had toasts where – yes! – we all propose toasts. When we were younger we found the adults desperately tedious by this stage: they were clearly drunk, found the oddest things hilarious, and would hug us, breathing fume-laden declarations of affection into our faces.

‘Lizzy goes first,’ said Chin, giving me a shove.

‘I’d like to toast Mr and Mrs Franks, and Tommy the dog,’ I said, getting up and downing the rest of my wine.

‘Hurray!’ said the others, except Gibbo and Rosalie.

‘They live in the village in Norfolk where we go on holidays. They’re gorgeous,’ said Chin. ‘You’ll meet them there this summer. It’s wonderful.’

Gibbo and Rosalie, bound together by fear of the unknown and the solidarity of the outsider, shot each other a look of trepidation.

‘Jess, you next!’ Tom yelled, prodding her in the thigh.

‘I want to toast Mr and Mrs Franks too,’ said Jess, determinedly.

‘You can’t,’ I said. ‘That was my idea. Think of someone else.’

‘I miss them,’ said Jess, her lower lip wobbling. Jess cries more easily than anyone I know, especially after wine.

‘Me too,’ said Chin, gazing into her glass. ‘I hope Mr Franks’s hip is OK.’

‘My turn,’ said Mike, standing up straight and holding his glass high in the air. ‘To…to Mr and Mrs Franks and Tommy the dog.’

We all fell about laughing, except Jess. ‘Mike! Be serious.’ She glared at him.

‘I stand by my toast,’ said Mike. ‘I send waves of love and vibes of massage to them, especially Mr Franks and his hip.’

‘Oh, Mike,’ said Jess, ‘don’t take the p-piss. You are mean.’

‘Sorry, darling,’ said Mike. ‘I change my toast. To my lovely new wife.’

‘To Mike’s lovely new wife,’ we all chorused. Rosalie beamed up at him.

Mum got up next. ‘I would like to toast Kate,’ she said quietly. ‘It was thirty-three years ago this week that Tony met her and we always remember him today, but I want Kate to know we all…Anyway, we do. To Kate.’

‘To Kate,’ we echoed, and Kate looked embarrassed and buried her face in her glass.

Mike opened another bottle as Dad stood up. ‘To the district council and their planning department,’ he said darkly, and drained his glass.

Jess and I rolled our eyes. Dad is always embroiled in some dispute over the field next to our little orchard, which is owned by the local council. They’re always threatening to chop down the trees opposite the house, or remove the lovely old hedgerow that flanks it and similarly stupid things.

‘The district council,’ came the weary reply.

It was Tom’s turn. He stood up slowly and surveyed the room. I noticed then, with a sense of unease, that he had a red wine smile: the corners of his mouth were stained with Sainsbury’s Cabernet Sauvignon. ‘The time has come…’ he began, and stopped. He swayed a little, and fell backwards into his seat. We all roared with laughter and raised our glasses to him. Somehow he got up again. ‘The time has come,’ he repeated, glazed eyes sweeping the room. ‘I want to tell you all something. I want to be honest with you.’

Kate looked alarmed. ‘What is it, darling?’ she asked, balling her napkin in one hand.

Tom waved his arm in a grandiloquent gesture. ‘You all think you know me, yes? You don’. None of you. Why don’t we tell the truth here? I’m not Tom.’

‘What’s he talking about?’ Rosalie whispered, horrified, to Mike. He shushed her.

‘I’m not the Tom you think I am, that Tom,’ said Tom, and licked his lips. ‘None of us tells the truth. Listen to me. Please.’

And this time we did.

‘I want to tell you all. You should know now. Listen, happy Christmas. But you should know, I can’t lie any more to you.’

‘Tom,’ I said, as the cold light of realisation broke over me and I suddenly saw what he’d been going on about. ‘Tom, tell us.’

‘I don’t think we’re honest with each other,’ he went on. ‘None of us. I think we should all tell each other the truth more. So I’m going to start. I’m gay. I’m Tom. I’m gay.’

The old clock on the wall behind him ticked loudly, erratically, as it must have done for over a hundred years. I gazed into my lap, then looked up to find everyone else doing the same. Someone had to say something, but I didn’t know what.

Then, from beside my father, Rosalie spoke: ‘Honey, is that all?’ she asked, reaching for a cracker. ‘You doll. I knew that the moment I laid eyes on you.’

Another silence.

‘Well, come on,’ said Rosalie. ‘Did any of you guys really not know?’

Kate cleared her throat and pouted. Tom was staring at her, with what seemed to be terror in his eyes. ‘I have to say I’ve always thought you might be, darling,’ she said. She reached across the table for his hand.

‘Er…me too,’ said Chin, and my mother nodded.

‘And me,’ Jess added, her lip wobbling again. ‘I love you, Tom.’

‘Oh, do be quiet, you fantastically wet girl,’ said Tom. A tear plopped on to Jess’s plate.

‘Good on you, mate,’ said Gibbo.

‘Come on, Mike,’ Rosalie appealed to her husband. ‘Didn’t you wonder?’

‘I must say I did,’ muttered Dad, which says it all, really. If Kate and Dad – people who think ‘friend of Dorothy’ refers to someone who is acquainted with Maisie Laughton’s sister in the next village – can be aware of Tom’s sexuality, then who had he thought he was kidding?

Tom looked discomfited. It must be awful to get seriously drunk and reveal your darkest secret to your family, only to discover that they knew it already.

‘What about you, Lizzy?’ said Tom. ‘Didn’t you wonder why I never talked about girls? Or boys?’

‘Not really,’ I said. ‘I just thought you might be and you’d tell me if you wanted to.’

Mike agreed. ‘I always wondered, Tom, you know. You asked for that velvet eye-mask for your twenty-first. I wondered then whether you were going through a Maurice phase. Jolly brave of you, must have been nerve-racking telling us today. I cancel my toast to Rosalie. Stand up, everyone.’

Our chairs scraped on the old floorboards. ‘To Tom,’ he said. ‘You know…we’re proud of you. Er. You know. For being your way. Here’s to Tom.’

‘You’re proud of me for being my way?’ said Tom, incredulously. ‘Good grief! This is like being on Oprah.’

‘Shut up, Tom,’ I said. We raised our glasses and intoned, ‘To Tom,’ and sat down again.

‘Well,’ said my mother. ‘Does anyone have room for another mince pie?’

SEVEN

By the time you’ve finished Christmas lunch, it’s incredibly late, and even though you’re stuffed you have to have tea with Christmas cake and Bavarian stollen, made by my mother, and by about nine p.m. you’re starving – the huge amount you have ingested over the last four hours has stretched your stomach, which is now empty and needs to be filled again. So you have the traditional Christmas ham, accompanied by the equally traditional Vegetable Roger, which is what Tom called it once when he was little, and which is Brusselsproutscarrotsroastpotatoescabbagestuffingand-breadsauce but not necessarily in that order, all whizzed up in the food-processor, then served with melted cheese on top. I console myself with the thought that this was what kept Mrs Miniver going through times of stress.

Because it was a time of stress. I’ve been underwhelmed in my time (George Alcott, 1995, step forward), but never quite so much as by Tom’s outing himself for the benefit of his family. The drama of the moment wasn’t matched by the significance of the announcement. Ever since Tom showed me the picture of Morten Harket that he kept hidden in a secret compartment of his Velcro-fastening, blue and red eighties wallet, I’ve always suspected that he was as gay as a brightly painted fence.

Immediately after lunch, Kate ordered him to bed for a nap. He protested loudly (what a great way to start your new life, being sent to bed by your mother), but he was so drunk it was for the best.

We sat downstairs, opened our presents, then had tea. Tom’s presents sat in a forlorn heap in the corner of the sitting room as we leaped up to thank each other, exclaimed with horror, amusement or pleasure at our gifts (all three, in Jess’s case, when she unwrapped a parcel from her flatmate without knowing it was a vibrator. I thought Dad was going to pass out).

I can’t say with my hand on my heart that my immediate family were overjoyed by their presents from me but, then, Jess gave me a ‘Forever Friends’ key-ring and Get Your Motor Runnin: 25 Drivin’ Classix for the Road on cassette, and I know the only place you can get those tapes is at a service station.

Mum and Kate both loved Tom’s presents: bottles of wine, gift-wrapped in a couple of rather creased Oddbins bags.

‘Ah, he knows just what to get his old aunt,’ chuckled my mother, affectionately.

‘Now, that’s what I call a present,’ said Kate, indulgently. ‘Bless him.’

‘Yes,’ Chin said sharply. ‘The masterstroke of asking for two separate plastic bags must have taken him ages.’ She had given her sisters-in-law individually crafted, velvet-beaded bags and was quite rightly annoyed at the reception lavished on Tom’s wine. As was I, but with less justification.

Later, as Mum and I were clearing up after the ham and Vegetable Roger I decided to wake Tom, so that he could enjoy a bit more of his Christmas Day, rather than coming to at three a.m. with a raging thirst. ‘I’m going to go and get Tom in a minute,’ I said to Mum, as we stood by the sink, washing the Things that are Too Big to Go in the Dishwasher.

Mum was in a philosophical mood. ‘Ah, Tom,’ she said, staring out of the window into the dark, windy garden. ‘Lizzy, did you really never ask him?’

‘No,’ I said firmly.

‘I don’t understand,’ she said, placing an earthenware pot on the draining-board. ‘Didn’t it ever come up?’

I felt a bit impatient, as if I was being accused of being a bad cousin/friend. ‘No, it didn’t.’

‘But why not?’ said Mum, lowering another dish into the soapy water.

‘Because you don’t ask big questions over a glass of wine or on the way into the cinema,’ I explained. ‘How do you say, “Hi, Tom, the tickets for Party in the Park have arrived and, by the way, do you prefer the manlove?” It was up to him to tell me if he wanted to. I’d do anything for him, he knows that.’

‘I know, darling,’ said Mum. ‘I do understand. I’m just glad he felt he could tell us now. It was all so different in My Day.’

‘Right,’ I said, hiding a smile in a tea-towel and not particularly wanting to hear about the famous ‘My Day’, although I’d very much like a specific calendar date for it at some point. In My Day blokes were called chaps, rad fem med students like my mother wore Pucci tunics, had big hair with black bows on top, applied their eyeliner wearing oven gloves while sitting on a bumpy bus, and marched during the day against the Midland Bank or Cape fruits while in the evening they grooved and bed-hopped at someone’s shabby stucco South Ken flat. In My Day you knew one chap who was ‘a queer’, usually a photographer or a film director, and you told people about it in a subtle way that implied you were a free-thinking liberal.

‘Well, it’s been quite a Christmas so far, hasn’t it?’ said Mum, wiping her hands. She advanced towards me. ‘And I’ve hardly talked to you since you got back, darling. How are you?’

‘I’m fine,’ I said, alarmed by the sudden maternal probing.

‘Was it very awful seeing David today?’ she said in a casual way, filling the kettle.

From the other side of the house I could hear Mike and Gibbo doing something to Chin that was making her scream. I put my elbows on the counter. ‘No, it was fine, thanks.’

‘Do you miss him?’ my mother persisted.

My elbows were soggy. I straightened hastily. ‘Erm…in what way?’

‘Oh, come on, Lizzy,’ my mother said, crossly, I thought. ‘Either you miss someone or you don’t.’

‘Not necessarily,’ I said, patting my damp arms. ‘What if there’s more than one factor involved? What if, say, you were madly in love with that person and would still be with them if it was up to you? Then you miss them. But what if that person slept with your friend in New York a month after he moved there and after he’d told you he wanted to spend the rest of his life with you? Well, yes, you still miss them, but you kind of don’t any more so much.’

My mother stared at me, involuntarily wrapping her arms round herself. ‘What?’ she said, with a catch in her throat. ‘I knew it was serious, but…oh, my darling…’

‘Yes, blah blah,’ I said. ‘But it turns out he’s a lying so-and-so and I was wrong about him, so let’s forget about it, shall we?’

‘Yes, let’s,’ said Mum, and gave me a hug. ‘I don’t know, you children. I know I’m always saying this, but in My Day…’

Thankfully, Kate came into the kitchen. ‘I was going to go and wake Tom. He’s been asleep for nearly six hours, you know. He told me he hadn’t slept at all the previous three nights because…he wanted to tell us.’ She smiled wanly.

‘I’ll go and get him,’ I said.

‘Be nice to him,’ said Kate. I stared at her. Kate, the scariest woman south of the M4? Kate, who made the postman cry? I expected her to support her son but in a bluff, Kate-ish way, but there were tears in her eyes.

‘Oh, Kate,’ I snapped. ‘Is it that much of a surprise to any of us? It’s hardly like finding out about John Major and Edwina Currie, is it? I mean…’ I tailed off. She was looking at me in a really scary way. ‘I’ll be off then,’ I said hurriedly, and ran out of the door. I bounded upstairs, shoes clacking on the wooden staircase, and knocked on Tom’s door. No answer. I banged again.

‘Hello…?’

‘Tom, it’s Lizzy. Can I come in?’

‘Lizzy…’ The voice was muffled and distant. ‘Hello…ouch.’

I pushed open the door. ‘Hello again,’ I said, and sat on the bed.

‘Hi,’ said Tom, from beneath his duvet. ‘Oh, God…’

‘Your mum sent me to get you.’

‘I can’t go down there and face them.’

‘Why not?’ I enquired.

‘I just can’t. I made such a fool of myself earlier.’

‘It doesn’t matter, silly,’ I said, stroking his feet. ‘They don’t care – none of us cares.’

Tom sat bolt upright and stared at me. His hair was incredibly amusing. It was springing out stiffly from his head at a 45-degree angle. I giggled.

‘That’s just it,’ Tom said angrily. ‘None of you cares. You knew all along. Here I am, carrying this awful secret around, living this double life where everyone at work and most of my other friends all know, and I haven’t told you, the people who mean most to me in the whole world. And when I pluck up courage to tell you this terrifying thing, all you do is laugh. Well, I wish I’d never bothered.’ He ran his fingers through his hair.

‘I’m so sorry,’ I whispered, horrified. ‘Honestly, none of us is laughing at you. We’re proud of you for having the guts to do it. Even if we did know. And I wasn’t laughing about that just now – your hair looks mad.’

‘I made a fool of myself,’ Tom moaned.

‘No, you didn’t,’ I said.

‘Yes, I did. Don’t lie to me, Lizzy.’ He stared up at me briefly, then buried his head under the duvet again. ‘Just go away,’ he mumbled.

I decided honesty was the best option. ‘Well, yes you did,’ I said quickly, ‘make a bit of a fool of yourself. But – oh, Tom, can’t you see why? You had red wine round your mouth, you were swaying and you fell over! That was why it was funny at first, and that’s what you’re probably remembering – if you can remember it,’ I added. ‘And the only way to show it doesn’t matter is if you come downstairs with me now, have a coffee, and make the others laugh so that they think you’re OK and they don’t have to be embarrassed about it.’

‘Perhaps you’re right. But…I just don’t want to go back down there.’

‘Oh, come off it, Tom,’ I said. ‘Get a grip. Look at the sorry collection of humans downstairs. Jess? What does she care if you’re gay, straight or a homicidal maniac? Gibbo? He’s only known you a day – I hardly think this is a body blow to him. Chin? Her friends are always coming out of the closet – look at Marcus.’

‘Marcus is gay?’ said Tom, pursing his lips and making snake eyes at me. ‘Fanbloodytastic.’

‘And, Tom,’ I continued, hoping I was on the home straight, ‘what do you think our family’s going to remember this Christmas for? You telling us what we already knew? I don’t think so.’

‘Mike…’

‘Exactly,’ I said, slapping his thigh. ‘When you look at it objectively, your news hardly compares with the ageing lawyer uncle bursting in on Christmas Eve with his busty bride of two days and acquaintance of four weeks. Think about it.’

‘Holy guacamole,’ said Tom, ‘you’re right.’

‘Of course I’m right. Come on, get up, you idiot.’

‘Lizzy,’ said Tom, hugging me, ‘you’re great.’

‘Yes, I am,’ I answered, and I allowed myself a moment of internal glow for my good deed.

‘I’m not playing Shoot Shag Marry with you again, though,’ said Tom, swinging his legs off the bed. He picked up a glass of water from beside his bed and glugged it down. ‘You’re terrible at choosing – you always pick completely the wrong people. And I don’t just mean David. Remember when you said you’d rather marry Duncan from Blue over Ryan Philippe?’

‘I stand by that,’ I said, as Tom pushed me through the door. ‘Duncan’s gorgeous and he’ll cut the mustard when he’s fifty, but Ryan’s pretty-boy looks will be gone in a flash.’

‘You’re hopeless,’ said Tom, as we trotted downstairs together. ‘Really you are. You’re the one who needs the sympathy, not me. You couldn’t spot a good thing coming if he was completely gorgeous and wearing a T-shirt that said “Good Thing Coming” on it.’

‘I know,’ I said, linking my arm through his.

‘I hope so,’ Tom said. ‘What about Miles? You could always shag him – he’d be up for it.’

‘You make me sound like a complete slapper,’ I said, not without a note of pride in my voice.

‘Oh, Lizzy,’ said Tom. ‘You wish. But listen to me. Anyone but David or that madman Jaden, and you’ll be fine.’

I couldn’t say, ‘But I don’t really want anyone but David,’ so I said nothing except ‘Come on, we’re here.’

As we stood in the hall, I looked through to the sitting room. There, framed in the doorway, my father was enthusiastically poking the fire with the end of the bellows and Mike was leaning against the mantelpiece, holding Dad’s whisky glass. ‘Bollocks, John,’ he said, as Dad jabbed ineffectually at another log. ‘No, that one there! Get that one over it, fella’ll burn for hours. No, no! Give it to me!’