Полная версия

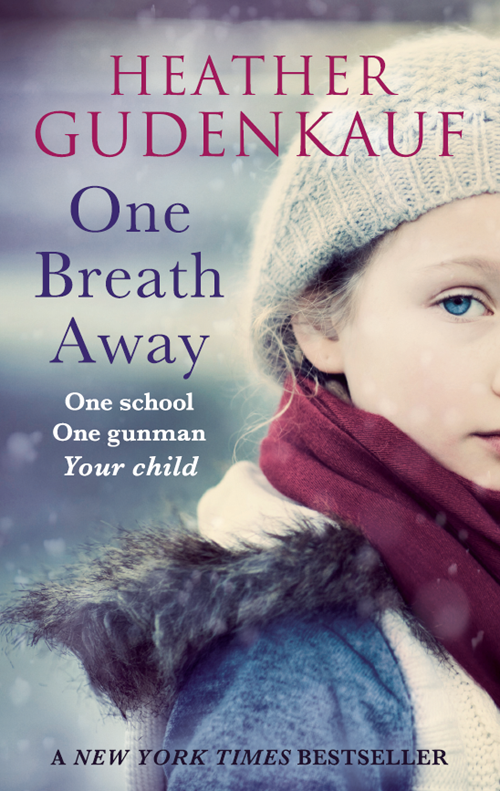

One Breath Away

Praise for Heather Gudenkauf

‘Brilliantly constructed, this will have you gripped until the last page …’

Closer

‘Deeply moving and lyrical … it will haunt you all summer.’

Company

5 stars ‘Gripping and moving’

Heat

‘Her technique is faultless, sparse and simple and is a master-class in how to construct a thriller … A memorable read … A technical triumph.’

Sunday Express

‘It’s totally gripping …’

Marie Claire

‘Tension builds as family secrets tumble from the closet.’

Woman & Home

‘This has all the ingredients of a Jodi Picoult novel.’

Waterstones Books Quarterly

‘Set to become a book group staple’

The Guardian

‘A skilfully woven thriller that will keep you hooked to the end’

Choice magazine

‘Jodi Picoult has some serious competition in Heather Gudenkauf.’

Bookreporter

‘Deeply moving and exquisitely lyrical, this is a powerhouse of a debut novel.’

Tess Gerritsen, No. 1 Sunday Times bestselling author

‘Fans of Jodi Picoult will devour this great thriller.’

Red

‘The author slowly and expertly reveals the truth in a tale so chillingly real, it could have come from the latest headlines.’

Publisher’s Weekly

‘Heart-pounding suspense and a compelling family drama come together to create a story you won’t be able to put down.’

Diane Chamberlain, bestselling author of

The Midwife’s Confession

‘This haunting psychological thriller lives up to expectation. Jodi Picoult or perhaps Joanne Harris are the nearest comparisons.’

Peterborough Evening Telegraph

‘A great thriller, probably the kind of book a lot of people would choose to read on their sun loungers. It will appeal to fans of Jodi Picoult.’

Radio Times

‘An enchantingly lyrical novel mixed with shockingly menacing overtones’

Newbooks

‘Gripping and powerful, right to the end’

Northern Echo

‘Secrets are slowly revealed by Gudenkauf’s skilled writing.’

NY Metro

‘A real page-turner’

Woman’s Own

About the Author

HEATHER GUDENKAUF is the critically acclaimed author of the New York Times bestselling novels The Weight of Silence and These Things Hidden. Her debut novel, The Weight of Silence , was picked for The TV Bookclub. She lives in Iowa with her family.

Read more about Heather and her novels at www.HeatherGudenkauf.com

Also available from Heather Gudenkauf

THE WEIGHT OF SILENCE

THESE THINGS HIDDEN

One Breath Away

Heather

Gudenkauf

For Alex, Anna and Grace

~My three wishes

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

As always, enormous gratitude goes to my agent, Marianne Merola, for her wisdom, guidance, attention to detail and her friendship. Thanks also to Henry Thayer for his behind-the-scenes support.

A thousand thanks to my editor, Miranda Indrigo, whose insights and suggestions are always spot on. Thanks also to all the folks at HQ—especially Margaret O’Neil Marbury and Valerie Gray. I’m so proud to call HQ my home.

Thank you to John and Kathy Conway and Howard and Shirley Bohr for opening up their homes and farms to me as I researched the novel. I always enjoy our time together.

Much appreciation goes to Mark Dalsing, whose advice in regard to police procedure and his early readings of the manuscript were invaluable.

A heartfelt thank-you goes out to my parents, Milton and Patricia Schmida, my brothers and sisters and their families, for their generous support and enthusiasm.

Much love and thanks to Scott, Alex, Anna and Grace—I couldn’t do it without you.

Holly

I’m in that lovely space between consciousness and sleep. I feel no pain thanks to the morphine pump and I can almost believe that the muscles, tendons and skin of my left arm have knitted themselves back together, leaving my skin smooth and pale. My curly brown hair once again falls softly down my back, my favorite earrings dangle from my ears and I can lift both sides of my mouth in a wide smile without much pain at the thought of my children. Yes, drugs are a wonderful thing. But the problem is that while the carefully prescribed and doled-out narcotics by the nurses wonderfully dull the edges of this nightmare, I know that soon enough this woozy, pleasant feeling will fall away and all that I will be left with is pain and the knowledge that Augie and P.J. are thousands of miles away from me. Sent away to the place where I grew up, the town I swore I would never return to, the house I swore I would never again step into, to the man I never wanted them to meet.

The tinny melody of the ringtone that Augie, my thirteen-year-old daughter, programmed into my cell phone is pulling me from my sleep. I open one eye, the one that isn’t covered with a thick ointment and crusted shut, and call out for my mother, who must have stepped out of the room. I reach for the phone that is sitting on the tray table at the side of my bed and the nerve endings in my bandaged left arm scream in protest at the movement. I carefully shift my body to pick up the phone with my good hand and press the phone to my remaining ear.

“Hello.” The word comes out half-formed, breathless and scratchy, as if my lungs were still filled with smoke.

“Mom?” Augie’s voice is quavery, unsure. Not sounding like my daughter at all. Augie is confident, smart, a take-charge, no one is ever going to walk all over me kind of girl.

“Augie? What’s the matter?” I try to blink the fuzziness of the morphine away; my tongue is dry and sticks to the roof of my mouth. I want to take a sip of water from the glass sitting on my tray, but my one working hand holds the phone. The other lies useless at my side. “Are you okay? Where are you?”

There are a few seconds of quiet and then Augie continues. “I love you, Mom,” she says in a whisper that ends in quiet sobs.

I sit up straight in my bed, wide awake now. Pain shoots through my bandaged arm and up the side of my neck and face. “Augie, what’s the matter?”

“I’m at school.” She is crying in that way she has when she is doing her damnedest not to. I can picture her, head down, her long brown hair falling around her face, her eyes squeezed shut in determination to keep the tears from falling, her breath filling my ear with short, shallow puffs. “He has a gun. He has P.J. and he has a gun.”

“Who has P.J.?” Terror clutches at my chest. “Tell me, Augie, where are you? Who has a gun?”

“I’m in a closet. He put me in a closet.”

My mind is spinning. Who could be doing this? Who would do this to my children? “Hang up,” I tell her. “Hang up and call 9-1-1 right now, Augie. Then call me back. Can you do that?” I hear her sniffles. “Augie,” I say again, more sharply. “Can you do that?”

“Yeah,” she finally says. “I love you, Mom,” she says softly.

“I love you, too.” My eyes fill with tears and I can feel the moisture pool beneath the bandages that cover my injured eye.

I wait for Augie to disconnect when I hear three quick shots, followed by two more and Augie’s piercing screams.

I feel the bandages that cover the left side of my face peel away, my own screams loosening the adhesive holding them in place; I feel the fragile, newly grafted skin begin to unravel. I am scarcely aware of the nurses and my mother rushing to my side, tearing the phone from my grasp.

Augie

My pants are still damp from when Noah Plum pushed me off the shoveled sidewalk into a snowbank after we got off the bus and were on our way into school this morning. Noah Plum is the biggest asshole in eighth grade but for some reason I’m the only one who has figured this out and I’ve only lived here for eight weeks and everyone else has lived here for their entire lives. Except for maybe Milana Nevara, whose dad is from Mexico and is the town veterinarian. But she moved here when she was two so she may as well have been born here, anyway.

The classroom is freezing and my fingers are numb with the cold. Mr. Ellery says it’s because it is not supposed to be below zero at the end of March and the boiler has been put out to pasture. Mr. Ellery, my teacher and one of the only good things about this school, is sitting at his desk grading papers. Everyone, except Noah, of course, is writing in their notebooks. Each day after lunch we start class with journal time and we can write about anything we want to during the first ten minutes of class. Mr. Ellery said we could even write the same word over and over for the entire time and Noah asked, “What if it’s a bad word?”

“Knock yourself out,” Mr. Ellery said, and everyone laughed. Mr. Ellery always gives time for people to read what they’ve written out loud if they’d like to. I’ve never shared. No way I’m going to let these morons know what I’m thinking. I’ve read Harriet the Spy and I keep my notebook with me all the time. Never let it out of my sight.

In my old school in Arizona, there were over two hundred eighth graders in my grade and we had different teachers for each subject. In Broken Branch there are only twenty-two of us so we have Mr. Ellery for just about every subject. Mr. Ellery, besides being really cute, is the absolutely best teacher I’ve ever had. He’s funny, but never makes fun of anyone and isn’t sarcastic like some teachers think is so hilarious. He also doesn’t let people get away with making crap out of anyone. All he has to do is stare at the person and they shut up. Even Noah Plum.

Mr. Ellery always writes a journal prompt on the dry erase board in case we can’t think of what to write about. Today he has written “During spring break I am going to …”

Even Mr. Ellery’s stare doesn’t work today; everyone is whispering and smiling because they are excited about vacation. “All right, folks,” Mr. Ellery says. “Get down to work and if we have some time left over we’ll play Pictionary.”

“Yesss!” the kids around me hiss. Great. I open my notebook to the next clean page and begin writing.

“During spring break we’re going to fly back to Arizona to see our mother.” The only sounds in the classroom are the scratch of pencils on paper and Erika’s annoying sniffles; she always has a runny nose and gets up twenty times a day to get a tissue. “I don’t care if I ever see snow or cows ever again. I don’t care if I ever see my grandfather again.” I am hoping with all my might that instead of coming back to Broken Branch after spring break, my mother will be well enough for us to come home. My grandfather tells us this isn’t going to happen. My mother is far from being able to come home from the hospital. My mom will be in Arizona until she is out of the hospital and well enough to get on a plane and come here so Grandma and Grandpa, who I met for the first time ever a couple months ago, can take care of all of us. But it doesn’t matter what my grandpa says—after spring break, I am not coming back to Broken Branch.

A sharp crack, like a branch snapped in half during an ice storm, makes me look up from my notebook. Mr. Ellery hears it, too, and stands up from behind his desk and walks to the classroom door, steps into the hallway and comes back in shrugging his shoulders. “Looks like someone broke a window at the end of the hallway. I’m going to go check. You guys stay in your seats. I’ll be right back.”

Before he can even leave the classroom the shaky voice of Mrs. Lowell, the school secretary, comes on the intercom. “Teachers, this is a Code Red Lockdown. Go to your safe place.”

A snort comes from Noah. “Go to your safe place,” he says, mimicking Mrs. Lowell. No one else says a thing and we all stare at Mr. Ellery, waiting for him to tell us what to do next. I haven’t been here long enough to know what a Code Red Lockdown is. But it can’t be good.

Mrs. Oliver

The morning the man with the gun walked into Evelyn Oliver’s classroom, she was wearing two items she had vowed during her forty-three-year career as a teacher never to wear. Denim and rhinestones. Mrs. Oliver was a firm believer that a teacher should look like a teacher. Well-groomed, blouses with collars, skirts and pantsuits crisply ironed, dress shoes polished. None of that nonsense younger teachers wore these days. Miniskirts, tennis shoes, plunging necklines. Tattoos, for goodness’ sake. For instance, Mr. Ellery, the young eighth-grade teacher, had a tattoo on his right arm. A series of bold black slashes and swoops that Mrs. Oliver recognized as Asian in origin. “It means teacher in Chinese,” Mr. Ellery, wearing a sleeveless T-shirt, told her after, embarrassingly, he caught her staring at his deltoid muscle one stifling-hot August afternoon during in-service week when all the teachers were preparing their classrooms for the school year. Mrs. Oliver sniffed in disapproval, but really she couldn’t help but wonder how painful it must be to have someone precisely and methodically inject ink into one’s skin.

Casual Fridays were the worst, with teachers, even the older ones, wearing denim and sweatshirts emblazoned with the school name and logo—the Broken Branch Consolidated School Hornets.

But on this unusually bitter March day, the last day school was in session before spring break, Mrs. Oliver had on the denim jumper she now knew she was going to die while wearing. Shameful, she thought, after all these years of razor-sharp pleats and itchy support hose.

Last week, after all the other third graders had left for the day, Mrs. Oliver had tentatively opened the crumpled striped pink-and-yellow gift bag handed to her by Charlotte, a skinny, disheveled eight-year-old with shoulder-length, burnished-black hair that chronically housed a persistent family of lice.

“What’s this, Charlotte?” Mrs. Oliver asked in surprise. “My birthday isn’t until this summer.”

“I know,” Charlotte answered with a gap-toothed grin. “But my mom and me thought you’d get more use out of it if I gave it to you now.”

Mrs. Oliver expected to find an apple-scented candle or homemade cookies or a hand-painted birdhouse inside, but instead pulled out a denim stone-washed jumper with rhinestones painstakingly arranged in the shape of a rainbow twinkling up at her. Charlotte looked expectantly up at Mrs. Oliver through the veil of bangs that covered her normally mischievous gray eyes.

“I Bedazzled it myself. Mostly,” Charlotte explained. “My mom helped with the rainbow.” She placed a grubby finger on the colorful arch. “Roy V. Big. Red, orange, yellow, violet, blue, indigo, green. Just like you said.” Charlotte smiled brightly, showing her small, even baby teeth, still all intact.

Mrs. Oliver didn’t have the heart to tell Charlotte that the correct mnemonic for remembering the colors in the rainbow was Roy G. Biv, but took comfort in that fact that she at least knew all the colors of the rainbow if not the proper order. “It’s lovely, Charlotte,” Mrs. Oliver said, holding the dress in front of her. “I can tell you worked hard on it.”

“I did,” Charlotte said solemnly. “For two weeks. I was going to Bedazzle a birthday cake on the front but then my mom said you might wear it more if it wasn’t so holiday-ish. I almost ran out of beads. My little brother thought they were Skittles.”

“I will certainly get a lot of wear out of it. Thank you, Charlotte.” Mrs. Oliver reached over to pat Charlotte on the shoulder and Charlotte immediately leaned in and wrapped her arms around Mrs. Oliver’s thick middle, pressing her face into the buttons of her starched white blouse. Mrs. Oliver felt a tickle beneath her iron-gray hair and resisted the urge to scratch.

It was Mrs. Oliver’s husband, Cal, who had convinced her to wear the dress. “What can it hurt?” he asked just this morning when he caught her standing in front of her open closet, looking at the jumper garishly glaring right back at her.

“I don’t wear denim to school, and I’m certainly not going to start wearing it just before I retire,” she said, not looking him in the eye, remembering how Charlotte had rushed eagerly into the classroom at the beginning of the week to see if she was wearing the dress.

“She worked on it for two weeks,” Cal reminded her at the breakfast table.

“It’s not professional,” she snapped, thinking of how on each passing day this week, Charlotte’s shoulders wilted more and more as she entered the room to find her teacher wearing her typical wool-blend slacks, blouse and cardigan.

“Her fingers bled,” Cal said through a mouthful of oatmeal.

“It’s supposed to be ten below outside today. It’s too cold to wear a dress,” Mrs. Oliver told her husband, miserably picturing how Charlotte wouldn’t even look her way yesterday, defiantly pursing her lips and refusing to answer any questions directed at her.

“Wear long johns and a turtleneck underneath,” her husband said mildly, coming up behind her and kissing her on the neck in the way that even after forty-five years of marriage caused her to shiver deliciously.

Because he was right—Cal was always right—she had brushed him away in irritation and told him she was going to be late for school if she didn’t get dressed right then. Wearing the jumper, she left him sitting at the kitchen table finishing his oatmeal, drinking coffee and reading the newspaper. She hadn’t told him she loved him, she hadn’t kissed his wrinkled cheek in goodbye. “Don’t forget to plug in the Crock-Pot,” she called as she stepped outside into the soft gray morning. The sun hadn’t emerged yet, but it was the warmest it would be that day, the temperature tumbling with each passing hour. As she climbed into her car to make the twenty-five-minute drive from her home in Dalsing to the school in Broken Branch, she didn’t realize it could be the last time she made that journey.

It was worth it, she supposed, after seeing Charlotte’s face transform from jaded disappointment to pure joy when she saw that Mrs. Oliver was actually wearing the dress. Of course Cal was right. Wearing the impractical, gaudy thing wouldn’t hurt anything; she’d had to suffer the raised eyebrows in the teacher’s lounge, but that was nothing new. And it obviously had meant a lot to Charlotte, who was now cowering in her desk along with fifteen other third graders, gaping up at the man with the gun. At least, Mrs. Oliver thought, shocking herself with the inappropriateness of the idea, if he shot her in the chest, she couldn’t be buried in the damn thing.

Meg

I’m trying to figure out what I’m going to do with all my free time for the next four days as I drive idly around Broken Branch in my squad car. This will be the first year that I won’t have Maria with me for spring break. By the looks of things, spring doesn’t seem like it will be appearing any time soon, even though it officially arrived two days earlier.

By rights, Tim should be able to have Maria this vacation; she’s spent the past two with me. But I had it all planned out for tomorrow, my day off. We were going to bake Dutch letters, flaky almond-flavored cookies, the one family tradition I’ve kept from when I was young. Afterward we were going to pitch a tent and have an old-fashioned campout in the living room. Then we were going to take advantage of the freak snowstorm to go snowshoeing at the bottom of Ox-eye Bluff with hot chocolate and marshmallows and oyster chowder when we got home. I even persuaded Kevin Jarrow, the part-timer on our police force, to pick up my Saturday shift so I could spend it with Maria. But this time Tim insisted. He finally scored a full five days off from his job as an EMT in Waterloo, where we both grew up.

“Listen, Meg,” he said when he called me the day before yesterday. “I don’t ask for much, but I really want Maria this school break….”

“She’s not an item on your grocery list,” I said hotly. “I thought we had this all figured out.”

“You had it all figured out,” he said. Which was true. “I want to spend a few days with her and I don’t think there’s anything unreasonable about that.”

“Where did this suddenly come from?” I asked.

“Hey, I’ll take any minute I can get with Maria and you know it. Besides, you’ve had her the past two holidays.” He was getting angry now. I imagined him sitting in the duplex we once shared, rubbing his forehead the way he did when he was frustrated.

“I know,” I said softly. “I just had it all planned out.”

“You could always come spend some of the time with us,” he said cautiously. I sighed. I was too tired to have this conversation. “Meg, you know I never did the things you thought I did.” Here we go, I thought. Every few months Tim insists that he didn’t have the affair with his coworker, that she was an unstable liar who had wanted something more, but whom he had rebuffed. Some days I half believe him. This isn’t one of those days.

“You can pick her up on Wednesday after school,” I told him.

“I was hoping tomorrow, after I get done with work. Around noon.”

“She’ll miss her last day of school before vacation. That’s when they do all the fun things.” It sounded lame, I know, but it was all I had.

“Meg,” he said in that way he has. “Meg, please …”

“Fine,” I snapped.

So yesterday I said goodbye to my beautiful, funny, sweet, perfect seven-year-old daughter. “I’ll call you every day,” I promised her, feeling like I was saying goodbye forever. “Twice.”

“Bye, Mom,” she said, swiping a quick kiss across my cheek before climbing into Tim’s car.

“If it hasn’t all melted, we’ll go snowshoeing when you get back,” I called after her.

“So, we’ll be at my folks tomorrow night for dinner and at my sister’s on Sunday.” His face turned serious. “I ran into your mom last week.”

“Oh,” I said as if I didn’t care.

“Yeah, they’d really like to see Maria.”

“I bet they would,” I grumbled.

“Is it okay if I take her over to see them?”

I shrugged. “I guess.” My parents weren’t bad people, just not particularly good people. “Promise me you won’t leave her at the trailer, it’s a death trap. And make sure Travis isn’t hanging around when you visit.” My brother, Travis, is one of the main reasons I became a police officer. Growing up he made my parents’ lives miserable and mine pure hell. It seemed like every week a police officer was at the door of our trailer, Travis in tow. They gave him more than enough chances to get his shit together and he blew it time and time again. It wasn’t until the summer I was thirteen and Travis was sixteen, when he threatened my father with a kitchen knife, smacked my mother across the face and ripped out a chunk of my hair as I tried to pull him away from them, that the police finally got serious.

“What do you want to do?” Officer Stepanich, a frequent visitor to our home, asked wearily. His young female partner, Officer Demelo, stood by silently, taking in the broken glass, the knocked-over chairs, the bald spot on the top of my head. Welcome to our lovely home, I wanted to say, but instead my face burned with shame.