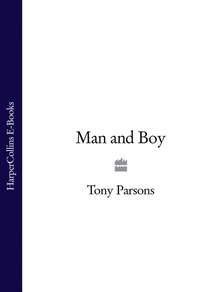

Полная версия

Man and Wife

Richard was not a bad guy. Even I could see that. My ex-wife wouldn’t be married to him if he was any kind of child-hater. I knew, even in my bleakest moments, that there were worse step-parents than Richard. Not that anyone says step-parent any more. Too loaded with meaning.

Pat and I had both learned to call Richard a partner –as though he were involved in an exciting business venture with the mother of my son, or possibly a game of bridge.

The thing that drove me nuts about Richard, that had me raising my voice on the phone to my ex-wife – something I would really have preferred to avoid – was that Richard just didn’t seem to understand that my son was one in a million, ten million, a billion.

Richard thought Pat needed improving. And my son didn’t need improving. He was special already.

Richard wanted my son to love Harry Potter, wooden toys and tofu. Or was it lentils? But my son loved Star Wars, plastic light sabres and pizza. My son stubbornly remained true to the cause of mindless violence and carbohydrates with extra cheese.

At first Richard was happy to play along, back in the days when he was still trying to gain entry into Gina’s pants. Before he was finally granted a multiple-entry visa into those pants, before he married my ex-wife, my son’s mum, Richard used to love pretending to be Han Solo to my son’s Luke Skywalker. Loved it. Or at least acted like he did.

And quite frankly my son would warm to Saddam Hussein if he pretended to be Han Solo for five minutes.

Now Richard was no longer trying, or he was trying in a different way. He didn’t want to be my son’s friend any more. He wanted to be more like a parent. Improving my boy.

As though improving someone is any kind of substitute for loving them.

You make all those promises to your spouse and then one day you get some lawyer to prove that they no longer mean a thing. Gina was part of my past now. But you don’t get divorced from your children. And you can never break free of your vows to them.

That’s what Paris was all about.

I was trying to keep my unspoken promises to my son. To still matter to him. To always matter. I was trying to convince him, or perhaps myself, that nothing fundamental had changed between us. Because I missed my boy.

When he was not there, that’s when I really knew how much I loved him. Loved him so much that it physically hurt, loved him so much that I was afraid some nameless harm would come to him, and afraid that he was going to forget me, that I would drift to the very edge of his life, and my love and the missing would all count for nothing.

I was terrified that I might turn up for one of my access visits and he wouldn’t be able to quite place me. Ridiculous? Maybe. But we spent most of the week apart. Most of the weekends, too, even with our legally approved trysts. I was never there to tuck him in, to read him a story, to dry his eyes when he cried, to calm his fears, to just be the man who came home to him at night. The way my old man was there for me.

Can you be a proper dad in days like these? Can you be a real father to your child if you are never around?

Already, just two years after he went to live with his mother, I was on the fast track to becoming a distant figure. Not a real dad at all. A weekend dad, at the very best. As much of a pretend dad as Richard. That was not the kind of father I wanted to be. I needed my son to be a part of my life.

My new life.

Cyd and I had been married for just over a year.

It had been a great year. The best year ever. She had become my closest friend and she hadn’t stopped being my lover. We were at that stage when you feel both familiarity and excitement, when things are getting better and nothing has worn off, that happy period when you divide your time between building a home and fucking each other’s brains out. Shopping at Habitat and Heal’s followed by wild, athletic sex. You can’t beat it.

Cyd was the nicest person I knew, and she also drove me crazy. The only reason I went to the gym was because I didn’t want her to stop fancying me. My sit-ups were all for her. I hoped it would always be that way. But if you have been badly burned once, you can never be totally sure. After you have taken a spin through the divorce courts, forever seems like a very long time. And maybe that’s a positive thing. Maybe that stops you from treating the love of your life like a piece of self-assembly furniture.

It wasn’t like that with my son. I planned to stay with Cyd until we were both old and grey. But you never know, do you? In my experience, relationships come and go but being a parent lasts a lifetime. What’s the expression?

Till death do us part.

There were lots of things we were planning to do in Paris.

Pat wanted to go up the Eiffel Tower, but the queues were dauntingly long, so we decided to save it for some other time. I contemplated taking him to the Louvre, but I decided he was too small and the museum was too big.

So what we did was take a bateau-mouche down the Seine and then grabbed a couple of croque-monsieurs in a little café in the Marais.

‘French cheese on toast,’ Pat said, tucking in. ‘This is really delicious.’

After that we went for a kickabout in the Jardin du Luxembourg, booting his plastic football around under the chestnut trees while young couples necked on park benches and pampered dogs sauntered around with their noses in the air and everybody smoked as though it was the fifties.

Apart from the boat trip down the river, and the fancy cheese on toast, it wasn’t so different from our usual Sundays. But it felt special, and I think our hearts were lighter than they ever were in London. It was one of those days that you feel like putting in a bottle, so you can keep it for the rest of your life and nobody can ever take it away from you.

It all went well until we got back to the Gare du Nord. As soon as we went up to the departure gates on the station’s first floor, you could see something was wrong. There were people everywhere. Backpackers, businessmen, groups of tourists. All stranded because there was something on the line. Leaves or refugees? Nobody knew.

But there were no trains coming in or leaving.

That’s when I knew we were in trouble.

I was glad that my own father was not alive to see all of this. The shock would have killed him, I swear to God it would.

But I knew in my heart that I didn’t spend endless hours with my own dad. My old man never took me to Paris for the day.

I may have grown up with my dad under the same roof, but he worked six days a week, long hours, and then he came home speechless with exhaustion, sitting there eating his cooked dinner in front of the TV, reflecting silently on the latest dance routine from Pan’s People.

My old man was separated from me by the need for work and money. I was separated from Pat by divorce and residency orders. Was it really so different? Yes, it was different.

Even if I rarely saw my father – and perhaps I am kidding myself, but even now I believe I can recall every kickabout I ever had with my old man, every football match we went to together, every trip to the cinema – my father was never afraid that someone would steal me away, that I might start calling some other man dad.

He went through a lot in his life, from a dirt-poor childhood to world war to terminal cancer. But he never had to go through that.

Wait until your father gets home, I was told by my mum, again and again.

And so I did. I spent my childhood waiting for my father to come home. And perhaps Pat waited too. But he knew in his heart that his father was never coming home. Not any more.

My old man thought that the worst thing in this world you can be is a bad parent to your child. But there’s something almost as bad as that, Dad.

You can be a stranger.

And of course I wanted my son to have a happy life. I wanted him to be a good boy for his mother, and to get on okay with her new husband, and to do well at school, and to realise how lucky he was to have found a friend like Bernie Cooper.

But I also wanted my son to love me the way he used to love me.

Let’s not forget that bit.

two

By the time the black cab finally crawled into the street where he lived, Pat was fast asleep.

I rarely saw my son sleeping these days, and I was surprised how it seemed to wipe away the years. Awake, his sweet face seemed permanently on guard, glazed with the heart-tugging vigilance of a child who has had to find a place between his divorced parents. Awake, he was sharp-eyed and wary, constantly negotiating the minefield between a mother and father who at some point in his short life had grown sick of living under the same roof. But, asleep, he was round-faced and defenceless again, his flimsy shields all gone. Not a care in the world.

The lights in his home were blazing. And they were all out on the little pathway, lit up by the security light, waiting for our return.

Gina, my ex-wife, that face I had once fallen in love with now pinched with fury.

And Richard, her Clark Kent lookalike, gym-toned and bespectacled, every inch the smug second husband, offering comfort and support.

Even Uli the au pair was standing watch, her arms folded across her chest like a junior fishwife.

Only the enormous policeman who was with them looked vaguely sympathetic. Perhaps he was a Sunday dad, too.

Gina marched down the path to meet us as I paid the driver. I pushed open the cab door and gently scooped my son up in my arms. He was getting heavier by the week. Then Gina was taking him away, looking at me as though we had never met.

‘Are you clinically insane?’

‘The train –’

‘Are you completely mad? Or do you do these things to hurt me?’

‘I called as soon as I knew we weren’t going to make it home by bedtime.’

It was true. I had called them on a borrowed mobile from the Gare du Nord. Gina had been a bit hysterical to discover we were stranded in a foreign country. Lucky I had to cut it short.

‘Paris. Bloody Paris. Without even asking me. Without even thinking.’

‘Sorry, Gina. I really am.’

‘“Sorry, Gina,”’ she parroted. ‘“So sorry, Gina.”’

I might have guessed she was going to start the parrot routine. If you have been married to someone, then you know exactly how they argue. It’s like two boxers who have fought each other before. Ali and Frazier. Duran and Sugar Ray. Me and Gina. You know each other too well.

She did this when our marriage was starting to fall apart – repeating my words, holding them up and finding them wanting, throwing them back at me, along with any household items that were lying around. Making my apologies, alibis and excuses all seem empty and feeble. Below the belt, I always thought.

We actually didn’t fight all that often. It wasn’t that kind of marriage. Not until the very end. Although you would never guess that now.

‘We were worried sick. You were meant to be taking him to the park, not dragging him halfway round Europe.’

Halfway round Europe? That was a bit rich. But then wanton exaggeration was another feature of Gina’s fighting style.

I couldn’t help remembering that this was a woman who had travelled to Japan alone when she was a teenager and lived there for a year. Now that’s halfway round the world. And she loved it. And she would have gone back.

If she hadn’t met me.

If she hadn’t got pregnant.

If she hadn’t given up Japan for her boys.

For Pat and me. We used to be her boys. Both of us. It was a long time ago.

‘It was only Paris, Gina,’ I said, knowing it would infuriate her, and unable to restrain myself. We knew each other far too well to argue in a civilised manner. ‘It’s just like going down the road. Paris is practically next door.’

‘Only Paris? He’s seven years old. He has to go to school in the morning. And you say it’s only Paris? We phoned the police. I was ringing round the hospitals.’

‘I called you, didn’t I?’

‘In the end. When you had no choice. When you knew you weren’t going to get away with it.’ She hefted Pat in her arms. ‘What were you thinking of, Harry? What goes on in your head? Is there anything in there at all?’

How could she possibly understand what went on in my head? She had him every day. And I had him for one lousy day a week.

She was carrying Pat up the garden path now. I trailed behind her, avoiding eye contact with her husband and the au pair and the enormous cop. And what was that cop doing here anyway? It was almost as if someone had reported a possible kidnapping. What kind of nut job would do a thing like that?

‘Look, Gina, I really am sorry you were so worried.’ And it was true. I felt terrible that she had been phoning the hospitals, the police, thinking the worst. I could imagine how that felt. ‘It won’t happen again. Next Sunday I’ll –’

‘I’ll have to think about next Sunday.’

That stopped me in my tracks.

‘What does that mean? I can still see him next Sunday, can’t I?’

She didn’t answer. She was finished with me. Totally finished with me.

Tracked by her husband and the hired help, Gina carried our son across the threshold of her home, into that place where I could never follow.

Pat yawned, stretched, almost woke up. In a voice so soft and gentle that it did something to my insides, Gina told him to go back to sleep. Then Richard was between us, giving me an oh-how-could-you? look. Slowly shaking his head, and with this maddening little smile, he closed the door in my face.

I reached for the door bell.

I just had to get this straight about Sunday.

And that’s when I felt the cop’s hand on my shoulder.

Once I was the man of her dreams.

Not just the man who looked after her kid on Sundays. The man of her dreams, back in the years when all Gina’s dreams were of family.

Gina yearned for family life, ached for it, in the way that is unique to those who come from what were once called broken homes.

Her father had walked out just before Gina started school. He was a musician, a pretty good guitarist, who would never quite make it. Failure was waiting for him, in both the music business and the smashed families that he left in his wake. Glenn – he was Glenn to everyone and dad to no one, especially not his children – gave rock and roll the best years of his life. He gave the women and children he left behind nothing but heartache and sporadic maintenance payments.

Gina and her mother, who had given up a modestly successful modelling career for her spectacularly unsuccessful husband, were just the first of many. There would be more abandoned families like them – women who had been celebrated beauties in the sixties and seventies, and the children who were left bewildered by separation before they could ride a bike.

From her mother Gina got her looks, a perfect symmetry of features that she was always dismissive of, the way only the truly beautiful can be. From Glenn her inheritance was a hunger for a stable family life. A family of her own that nobody could ever take away. She thought she would find it with me because that was exactly where I came from. She thought I was some kind of expert on the traditional set-up of father, mother and child living in a suburban home, untouched by divorce statistics, unshakably nuclear. Until I met Gina, I always thought that my family was embarrassingly ordinary. Gina made us feel exotic – and that was true of my mum and dad, as well as me. This smiling blonde vision came into our world and up our garden path and into our living room, telling us we were special. Us.

Our friends all thought that Gina and I were too young for marriage. Gina was a student of Japanese, looking for a way to live her life in Tokyo or Yokohama or Osaka. I was a radio producer, looking for a way into television. And our friends all reckoned it was much too soon for wedding vows and a baby, monogamy and a mortgage. Ten years too soon.

They – the language students who thought the world was waiting for them, and the slightly older cynics at my radio station who thought they had seen it all before – believed that there were planes to catch, lovers to meet, drugs to be taken, music to be heard, adventures to be had, foreign flats to be rented, beaches to be danced on at dawn. And they were right. All of those things were waiting. For them. But we gave them up for each other. Then our son came along. And he was the best thing of all.

Pat was a good, sweet-natured baby, smiling for most of the day and sleeping for most of the night, as beautiful as his mother, ridiculously easy to love. But our life – already married, already parents, and still with a large chunk of our twenties to go – wasn’t perfect. Far from it.

It wasn’t just a job. Gina had given up a whole other life in Japan for her boys, and sometimes – when the money was tight, when I came home from work too tired to talk, when Pat’s brand-new teeth were painfully pushing through his shining pink gums and he could no longer sleep all night – she must have wondered what she was missing. But we had no real regrets. For years it was fine. For years it was what we had been waiting for. Both of us.

A family to replace the one that I had grown up with.

And a family to replace the one that my wife had never known.

Then I spent one night with a colleague from work. One of those pale Irish beauties who seemed a little bit smarter, and a little bit softer, than most of the women I worked with.

And it was madness. Just madness.

Because after Gina found out, we all had to start again.

I sent money every month.

The money was never late. I wanted to send it. I wanted to help bring up my son in any way I could. That was only right and proper. But sometimes I wondered about the money. Was it all being spent on Pat? Really? Every penny? How could I know that none of it was being blown on the guy my ex-wife married? Bloody Richard.

I didn’t know. I couldn’t know.

And even that was okay, but I felt like the money should give me certain basic human rights. Such as, I should be able to call my son whenever I needed to talk to him. It shouldn’t be a problem. It should be normal. And how I missed normal. A few days of normality, full board – what a welcome mini-break that would be.

But when I picked up the phone I always found I couldn’t dial the number. What if Richard – strange the way I called him by his first name, as if we were actually friends – answered? What then? Small talk? Small talk seemed inadequate for our situation. So words failed me, I replaced the receiver, and I didn’t make the call. I stuck to the schedule worked out in advance with Gina, and my only child and I might as well have been on different planets.

But I still felt like the monthly money – which my current wife, I mean my second wife, I mean my wife thought was a tad too generous, by the way, what with us wanting to move to a bigger place in a better area – should mean something.

It wasn’t as though I was some wayward bastard who didn’t want to know, who had already moved on to his new family, who was quite keen to forget all that went before. I was not like one of those scumbags. I was not like Gina’s old man. But what can you do?

I’m only his father.

My wife understood me.

My wife. That’s how I thought of her. Second wife always sounded plain awful. Like second home – something you get away to at the weekend and during the longer school holidays. Or second car – as if she was a rusty VW Beetle.

Second wife sounded like second-hand, second choice, second best – and Cyd deserved far better than all of that. All that second business wasn’t good enough for Cyd, didn’t describe her at all. And new wife – that was no good either.

Too much like trophy wife, too much like so-many-years-my-junior wife, too many images of dirty old men running off with their secretaries.

No – my wife. That’s her. That’s my Cyd.

Like Cyd Charisse. The dancer. The girl in Singin’ in the Rain who danced with Gene Kelly and never said a word. Because she didn’t have to. She had those legs, that face, that flame of pure fire. Gene Kelly looked at Cyd Charisse, and words were not necessary. I knew the feeling.

Cyd understood me. She would even understand about Sunday afternoon in Paris.

Cyd was my wife. That was it. That was all. And this life I was returning to now, it was not new, and it was second to nothing.

This was my marriage.

Before I went into our bedroom I checked on Peggy.

She was out for the count but she had kicked off her duvet and was clutching a nine-inch moulded-plastic doll to her brushed-cotton pyjamas. Peggy was a pale-faced, pretty child with an air of solemnity about her, even when she was what my mum would call soundo, meaning fast asleep.

The doll in her tiny fist was a strange-looking creature, cocoa-coloured but with long blonde hair and blue, blue eyes. Lucy Doll. Marketing slogan – I Love Lucy Doll. Made in Japan but aimed at the global market place. I was becoming an expert on this stuff.

There was nothing WASPy about Lucy Doll, nothing remotely Barbie about her. She looked a little like the blonde one in Destiny’s Child, or one of those new kind of singers, Anastacia and Alicia Keys and a few more I can’t name, who are so racially indeterminate that they look like they could come from anywhere in the world. Lucy Doll. She had fully poseable arms and legs. Peggy was crazy about her. I covered them both up with an official Lucy Doll duvet.

Peggy was Cyd’s child from her previous marriage to a handsome waste of space called Jim. This good-looking loser who did one right thing in his life when he helped to make little Peggy. Jim with his weakness for Asian girls. Jim with his weakness for big motorbikes that he kept crashing. He came round to our house now and then to see his daughter, although he was not on a fixed schedule like me with Pat. Peggy’s dad turned up more or less when he felt like it.

And his daughter was crazy about him.

The bastard.

I had met Peggy before I met Cyd. Back then Peggy was just the little girl who looked after my son, in those awful months when he was still fragile and frightened after I had split up with his mother. Peggy looked after Pat in his early days at school, spent so much time with him that they sometimes seemed like brother and sister. That bond was fading now that their lives were increasingly separate, now that Pat had Bernie Cooper and Peggy had a best friend of her own sex who also loved Lucy Doll, but Peggy still felt like more than my stepdaughter. It felt like I had watched her grow up.

I left Peggy clutching Lucy Doll and went quietly into our bedroom. Cyd was sleeping on her half of the bed, the sleep of a married woman.

As I got undressed she stirred, came half-awake and sleepily listened to my story about Pat and Paris and broken trains. She took my hands in hers and nodded encouragement. She got it immediately.

‘You poor guys. You and Pat will be fine. I promise you, okay? Gina will calm down. She’ll see you didn’t mean it. So how’s the weather in Paris?’

‘It was sort of cloudy. And Gina says she has to think about next Sunday.’

‘Give her a few days. She’s got a right to be mad. But you’ve got a right to take your boy to Paris. Jump in bed. Come on.’

I slipped between the sheets, feeling an enormous surge of gratitude. What Gina saw as an unthinking, reckless act of neglect Cyd saw as a good idea that went badly wrong. An act of love that missed the train home. She was biased, of course. But I said a prayer of thanks that I was married to this woman.

And I knew it wasn’t the wedding band that made her my wife, or the certificate they gave us in that sacred place, or even the promises we had made. It was the fact that she was on my side, that her love and support were there for me, and would always be there.