Полная версия

Grand Adventures

GRAHAM HUGHES

VISITED EVERY COUNTRY IN THE WORLD WITHOUT FLYING

When asked how can I afford to travel so much, I feel like retorting with: how can you afford your rent? To keep a dog? To have children? To smoke? When I travel, I have no rent to pay, so 100 per cent of the money I have can go on travel.

JAMIE MCDONALD

RAN 200 MARATHONS ACROSS CANADA

I spent three years saving up for a house. The only reason was because everyone else was doing that. I was just choosing it for someone else’s sake. So I bought a second-hand bicycle for 50 quid out of the newspaper and I flew to Bangkok. And then I cycled home back to Gloucester.

ANDY KIRKPATRICK

BIG WALL CLIMBING & WINTER EXPEDITIONS

Before my first trip to the Alps I was working in a job where I got £100 a week, and just the bus ticket from Sheffield to the Alps cost me £99! I saved one week’s pay, spent it on the ticket and packed in my job. Every penny we spent was considered.

JASON LEWIS

SPENT 13 YEARS CIRCUMNAVIGATING THE PLANET BY HUMAN POWER

I ended up in the clink [prison] in east London for trying to run out the door of the chandlery there with our shit bucket and a scrubbing brush, coming to the total of £4.20. I was rugby tackled by security guards at Woolworths. So yeah, we were just desperate.

© Alice Goffart and Andoni Rodelgo

© Tim and Laura Moss

MATT EVANS

TRAVELLED OVERLAND FROM THE UK TO VIETNAM

I bought a big ceramic savings pot that needed to be smashed to get all the money inside. Every day we came in from work and put all the loose change in our pockets into it. No excuses. This might sound silly but after a while it became normal, and when we finally had a grand ‘Smashing of the Jar’ ceremony, we had £962.28 in it. That’s quite a lot of money for a small daily ritual that didn’t seem to take much effort. The funny thing was, once we’d saved up the money without living like hermits or living on beans on toast, we looked at each other and wondered why we hadn’t been making these changes to our lives since we met. We hadn’t felt unduly broke, we hadn’t lost any friends, and we didn’t feel as though we’d worked our fingers to the bone. Yet somehow we’d saved enough money to have the adventure of a lifetime. All it took was a little thinking, a few tweaks and a bit of willpower.

SEAN CONWAY

FIRST PERSON TO COMPLETE A ‘LENGTH OF BRITAIN’ TRIATHLON

I don’t have much money, so I just got loads of credit cards. That kind of got the funding out of the way initially.

KEVIN CARR

RAN AROUND THE WORLD

Unless what you’re considering is crazy expensive, it’s probably much less hassle to work a part-time second job/overtime than it is to chase sponsors.

PATRICK MARTIN SCHROEDER

TRYING TO CYCLE TO EVERY COUNTRY IN THE WORLD

I know this: travelling made me richer, even if I have less money. The slower you travel, the less money you spend. Money is probably not the thing stopping you, but the fact that you have to leave your comfort zone. That you have to do something scary. Once you step over that line, once you are on the road, everything gets easier.

CHRIS MILLAR

CYCLED TO THE SAHARA

I worked as a rickshaw driver to save some pennies, get fit and learn the basics of bicycle maintenance.

NIC CONNER

CYCLED FROM LONDON TO TOKYO FOR £1,000

We realised with our pay cheques it wasn’t going to be too much of a budget we were going to be living on, so we thought, ‘Right. Let’s work with this and make it a challenge.’

JAMES KETCHELL

CYCLED ROUND THE WORLD, ROWED THE ATLANTIC, CLIMBED EVEREST

I was working as an account manager for an IT company. I moved back home with my parents; this made a big difference to my finances. Not particularly cool when you’re in your late twenties but it goes back to how much you want something. I took on an extra job delivering Chinese food in the evenings.

© Alastair Humphreys

A SHORT WALK IN THE WESTERN GHATS

I once walked 600 miles across southern India because I wanted a challenge but didn’t have the time or money to walk 6,000 miles. I was trying to understand what drives me to go on all these adventures I feel addicted to. In order to understand, I felt I had to push myself really hard…

Head thumping, heat shimmering, sun beating. The loneliness I felt in crowds of foreign tongues, staring at one foreign face. Bruised feet, dragging spirit, bruised shoulders slumped. Can’t think. Can’t speak. Just walk. The monotony of the open road.

These are common complaints on a difficult journey. I often get them all in a single day, and I know there will be more of the same tomorrow. Most days involve very little except this carousel of discomfort. It doesn’t sound like much of an escape.

Yet escape is a key part of the appeal of the road. All my adult life I have felt the need to get away. The intensity and frequency of this desire ebbs and flows but it has never gone altogether. Perhaps it is immaturity, perhaps a low-tolerance threshold. But there is something about rush hour on the London underground, tax return forms and the spirit-sapping averageness of normal life that weighs on my soul like a damp, drizzly November. It makes me want to scream. Life is so much easier out on the road. And so I run away for a while. I’m not proud of that, but the rush of freedom I feel each time I escape keeps me coming back for more. Trading it all in for simplicity, adventure, endurance, curiosity and perspective. For my complicated love affair with the open road.

Escaping to the open road is not a solution to life’s difficulties. It’s not going to win the beautiful girl or stop the debt letters piling up on the doormat. (It will probably do the opposite.) It’s just an escape. A pause button for real life. An escape portal to a life that feels real. Life is so much simpler out there.

But it is not only about running away. I am also escaping to attempt difficult things, to see what I am capable of. I don’t see it as opting out of life. I’m opting in. Total cost: £500, including flight

(Extract from There Are Other Rivers)

CROSSING A CONTINENT

With three weeks to spare, my friend Rob and I decided to cycle across Europe. We flew to Istanbul and began riding home. The maths was quite simple: we had to ride 100 miles a day, every single day. We had £100 each to spend (plus money for ferries), which meant a budget of £5 a day.

I remember the stinking madness of the roads of Istanbul. I remember our excitement as we made it out of the city. I remember reaching the Sea of Marmara and how refreshing it felt to run into the water to cool down. Then it was back on the bike and ride, ride, ride.

Cycling 100 miles a day was really tough for me back then and this was a gruelling physical challenge. But that was what we wanted. We were invited into a family’s home for strong coffee and fresh oranges. We peered at a dead bear beside the road. I waited for my friend for ages at the top of a winding hairpin pass in Greece. I was annoyed at his slowness. But then he arrived with his helmet full of sweets – like a foraged basket of blackberries – that a passing a driver had given him. Those bonus free calories tasted so good!

I remember the satisfaction of seeing the odometer tick over to ‘100’ each day. I remember the simple fun of finding a quiet spot to camp, in flinty olive groves as the sun set over the sea. Those were good days. Total cost: £100 plus flight

© Alastair Humphreys

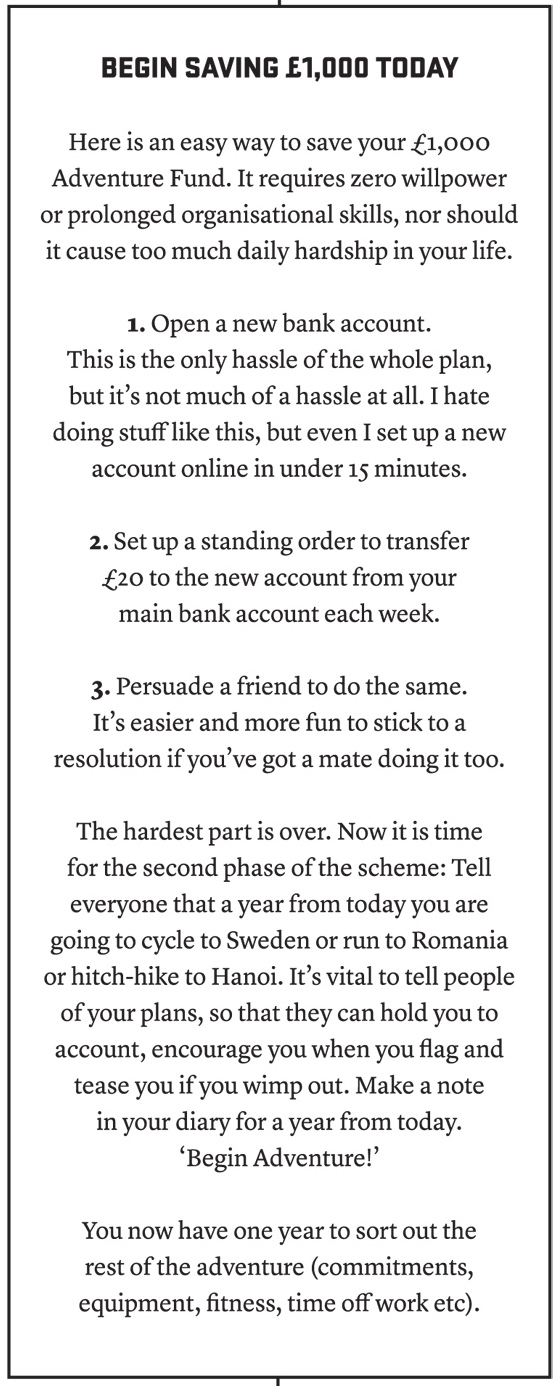

IS £1,000 REALLY ENOUGH MONEY FOR AN ADVENTURE?

There is an assumption that adventures have to be expensive. They need not be. This is particularly true if you overcome another assumption: that you have to fly far away in order to have an adventure. Hatching an adventure that begins and ends at your front door is not only cheaper, it’s also satisfying. It creates a story that is easier for your friends and family to engage with and get involved with, and it leaves you with fond memories every time you leave your front door in future.

So, if you are trying to do a big trip for less than £1,000, I recommend cutting the expense of a plane ticket. Cycle away from your front door on whatever bike you own or can borrow and see how far you get.

However, you can get some great bargains on plane tickets. For example, if you decide to commit £200 of your £1,000 to a plane ticket, a website like Kayak (www.kayak.co.uk/explore) shows enticing options of where you can go for that amount of money. Writing this now, I had a look at the website. I could fly from London to Nizhny Novgorod for £190. I have never even heard of Nizhny Novgorod but instantly my mind starts to fill with ideas…

Here’s a cursory budget outline to help you start making plans and to realise that trips are neither as complicated nor as expensive as you might fear.

— Boring but important stuff: insurance, vaccinations, first aid supplies: £200.

— Equipment that you don’t already own or can’t borrow from a mate: £400 will get you a lot of stuff from eBay.

— Costs along the way: ferries, repairs, visas, an ill-advised piss-up in a dangerous but exciting port: £200

— Daily food budget: £5 per day. You could easily live on half this amount, or twice this amount, according to how you like to travel. But £5 will buy you pasta, oats, bread, bananas, veg and a tin of tuna, even in an expensive part of the world. Never pay for water. Just refill your bottles from a tap, purifying the water if necessary.

With £200 remaining, you have enough for 40 days on the road at £5 a day. If you set off from your front door and cycle a pretty leisurely 60 miles a day, and have one day off each week, that still amounts to an impressive 2,000-mile journey. You could cycle from London to Warsaw and back, San Francisco to Vancouver and back, or Copenhagen to Marseille and back. New York to New Orleans and back is a bit far, but York to Orleans is definitely do-able… If you choose to walk, run or swim you won’t travel so fast but your equipment costs will be lower so you will have more days on the trail.

You might choose to spend a bit more or a bit less on different things. You’ll probably find your own budget spreadsheet to be a little more complicated than mine here. But I hope you are starting to realise that the financial element of an adventure is within your grasp.

If you are in the fortunate position of even being able to dream of undertaking a big adventure, getting hold of £1,000 may not be the biggest hurdle. After all, it’s less money than many holidays, kitchen upgrades, wedding dresses or TVs cost. But not many people have both plenty of money and plenty of time (at least not whilst they are still young enough to climb Rum Doodle without their knees hurting).

For many, the scarcest resource in life is time. That is why I wrote Microadventures, a book about squeezing local adventures into the confines of real life. Microadventures challenge you to look at how you spend the 24 hours you have each day and to try to re-prioritise things a little bit.

But grand adventures require more than 24 hours. If you’re yearning to cross a continent, chasing the days west until the sun sets into the ocean before you, you’ll need to find a bigger chunk of time. There is never an easy time to find that time. Too many people are willing to settle for waiting until they retire, and this always makes me sad. The actor Brandon Lee’s grave is inscribed with these words:

‘Because we don’t know when we will die, we get to think of life as an inexhaustible well. And yet everything happens only a certain number of times, and a very small number really. How many more times will you remember a certain afternoon of your childhood, an afternoon that is so deeply a part of your being that you can’t even conceive of your life without it? Perhaps four, or five times more? Perhaps not even that. How many more times will you watch the full moon rise? Perhaps twenty. And yet it all seems limitless …’

Have a look at www.deathclock.com; it’s one of my favourite websites! You add various parameters about your life (age, weight, gender, whether you smoke) and it will calculate the date you are likely to die. A big, unstoppable clock begins counting down the remaining seconds of your life.

I have the date of my predicted death scheduled into my diary. Morbid, perhaps, but it takes deadlines to spur most of us into action, and that non-extendable deadline scares the hell out of me. I have so much I want to get done before 8 September 2050!

Life, they say, is what happens while you’re busy making plans. Time is ticking, life is short. These days everyone is busy. We’re racing time, always chasing time. Bragging about how busy we are is one of our era’s favourite things to do. But, as the pithy viral Tweet said, ‘We all have the same 24 hours that Beyoncé has.’ It’s up to us to carve out time to make bootylicious stuff happen. When I was younger I would simply think of a trip, then go and do it. Now that I’m older and busier it’s more often a case of making a chunk of time available and then coming up with a plan that fits into that time slot.

There is no simple solution. This book will not solve the lack-of-time conundrum. I’d be rich if it did. But it might get you excited enough to resolve to solve it yourself: to begin the conversations with the people in your life – your family, your boss, yourself – about how it might be possible to pause the racing rhythm of daily life for long enough to do something different and really memorable. After all, each hour that passes, each dreary commute, each bleary Monday morning – these are hours on the hamster wheel that you have spent and will never be able to recoup or spend again. So spend them wisely.

One of my favourite feelings on expeditions is how much time I have. I don’t have more time, of course, I’ve just freed it up to do stuff that feels important to me. I wake at dawn, the diary is empty and the day stretches long before me. I drink tea and watch the sun rise. All I need to do today is make some miles. And then I will sit again, weary but satisfied, in some place I have never been before, and watch the sun set. The days are not busy, but they are full and fulfilling. I cherish spending that time. At home my days feel short and hurried. Yet at the end of most of them I’ve accomplished nothing memorable. What a waste!

I hope that this book persuades you to find a way to find time to fill your days with what feels important and worthwhile to you, not with the stuff that conventional society deems you ought to be doing.

‘The sooner you begin to get into this mind-set, the sooner you will have that big juicy chunk of time inked into your diary and the adventure can begin’

The first task is to think carefully about how you use your time now, and how you might be able to make some time for adventure. This isn’t about stirring your porridge into your coffee, sleeping in your work suit or other handy tips like that. For a big adventure you’ll need to clear a swathe of time – weeks at least, months, maybe even a year or two.

Begin by asking yourself these questions. I know they are hard, but try to answer them as positively as you can rather than instantly dismissing them as impossible in the circumstances of your life.

What is the biggest chunk of time you might be able to carve out for an adventure? Is this long enough to do what you’d like to do? Squeeze another week on at either end. Is that long enough? How much time do you need?

When in the next year might you have time? Can you block off a non-negotiable chunk of time in your diary? It might be quite far in the future, but once it’s in the diary you can treat it as sacrosanct.

What are your time constraints? Why can’t you go away?

If it’s work, do they truly need you all the time? Could your colleagues cope without you for a while? How much loyalty and time do you owe them? Beware of misplaced loyalty. Talk to your boss about how you might be able to free up some time. Don’t just second-guess them by saying ‘it’ll never happen. They can’t do anything about it’. Have the conversation. Tell them how important this is to you, explain the benefits it will have for you and your work performance.

Imagine you were suddenly bedridden for a couple of months. Would the world cope without you? How would it manage? Could you, therefore, bugger off on an adventure for a couple of months without the world collapsing?

Could you take a sabbatical from work? Maybe you could work from the road. If you resigned, could you get your job back when you return? Could you quit, then seek a new job when you return? Or apply for a new job now but agree not to begin the position for a few months?

If you are too financially constrained to stop working, are there ways you can free yourself a little? Can you clear your credit card debts, downsize your house or rent it out, or even take out a loan? Richard Parks’ parents re-mortgaged their house to help him accomplish his expedition dream of climbing the Seven Summits and bagging both Poles. Extreme measures, perhaps, but it is important to reflect upon how important this experience is to you. You can get more money in life, but not more time.

On expeditions you often need to take bold, decisive decisions that will have a significant impact on your chances of success or staying alive. You have to be confident, clear-headed and brave enough to back yourself. The wilderness is a place for positive decisions, pushing forwards and making shit happen. The sooner you begin to get into this adventurer’s mind-set, the sooner you will have that big juicy chunk of time inked into your diary and the adventure can at last begin.

WISE WORDS FROM FELLOW ADVENTURERS

SEAN, INGRID AND KATE TOMLINSON

CYCLED THE LENGTH OF THE AMERICAS

Kate was eight: the perfect age – old enough to remember and benefit from her experiences, but not yet a reluctant stroppy teenager!

HANNAH ENGELKAMP

WALKED ROUND WALES WITH A DONKEY

Often I’d get people saying, ‘Oh, well, I’m glad you’re doing it now while you’re young, while you can’, and they’d be people in their fifties. Sometimes I’d just think, ‘Oh, for heaven’s sake, you’re just giving yourself an easy excuse.’

ROSIE SWALE-POPE

RAN AROUND THE WORLD IN HER SIXTIES.

You’re a long time dead, so you might as well get on and do it whilst you are alive!

JAMIE BOWLBY-WHITING

RAFTED DOWN THE DANUBE

It’s not the days in the office that we’ll reflect upon with nostalgia when we are old.

SARAH OUTEN

TRAVELLED ROUND THE NORTHERN HEMISPHERE BY HUMAN POWER

Treat it as you would any other project. Identify what the project is, break it down into bits and put a time frame on it, then suddenly it can happen. Monitor your progress as you go along and learn stuff on the way. I think so long as you’re flexible in that plan and willing to change and adapt, then it’s not rocket science.

COLIN WILLOX

BACKPACKED THROUGH EUROPE

People are often paralysed by fear at the difficulties of making an adventure happen (‘where will I keep my car?’). There is no perfect time to go. So tie up the loose ends you can in a reasonable time, and leave. It will be messy. You’ll screw up. There are no guarantees. Remember that this is what you want, it’s why you’re going. If you didn’t, you would stay home.

PAUL RAMSDEN

TWO-TIME WINNER OF THE PIOLETS D’OR AWARD

It’s really hard [to make the time]. I’m busy. It’s hard to find the time to get fit. The most important thing is that I get the dates in the diary maybe a year in advance. It’s then non-negotiable – if I get work offers or party invites I can then say ‘sorry, I’ll be in India’. It’s a bit brutal. There’s no compromise. It’s massively important to set those dates, otherwise it would be much easier just not to bother.

ROLF POTTS

CIRCLED THE GLOBE WITH NO LUGGAGE OR BAGS

I’d say that procrastinating about the journey is tied into the core fears that keep us from travelling. We keep thinking that there will be a better time, a time when we have more money or fewer obligations, or when the world feels safer and more open. In truth it doesn’t take as much money as most people think, obligations are something we can manage, and the world is far safer than you might think from just watching news headlines.

KIRSTIE PELLING

FOUNDER OF THE FAMILY ADVENTURE PROJECT

We made a decision to go freelance to make time to spend with the children. We started a website to record our adventures. If you voice your ambitions out loud you are more likely to achieve them.

MENNA PRITCHARD

CLIMBER

[Things like time], they’re not the reasons – they’re the excuses. Aren’t they? I really believe that if you want something enough then you will find the time, scrape together the money, and overcome your fears… But it’s all about priorities. And I know because I’m completely guilty of it myself. Ever since I became a mum, I have used it as an excuse. An excuse for not having the adventures my heart desires. There comes a time when we have to say to ourselves, ‘stop making excuses’. That if something means so much to us then it’s worth working towards, it’s worth fighting for – and, dammit, it’s worth the struggle. I don’t want life to be about the battles I never fought, the barriers I never overcame, the excuses I made.

HELEN LLOYD

LONG-DISTANCE JOURNEYS BY BIKE, HORSE, RIVER AND ON FOOT

My job in engineering, although it started as a career, is now a means to an end. It’s how I earn money to do the things I really want. I now work short-term contracts, live cheap, save up and plan another journey. For me, the mix of travel and engineering job satisfies all my needs, which I couldn’t get from just one.

GRANT RAWLINSON

HUMAN-POWERED EXPEDITIONS BEGINNING AND ENDING ON INTERESTING MOUNTAIN SUMMITS

I have a full-time job as a regional sales manager based in Singapore, travelling around Asia spending lots of time eating very nice meals with customers and staying in beautiful hotels. All of which I do not appreciate as much as a lukewarm cup of instant soup in a freezing snow cave. What is wrong with me?!

SCOTT PARAZYNSKI

ASTRONAUT AND MOUNTAINEER

[A lack of time] can probably be viewed as a cop-out on many occasions. A couple of times in my life, I’ve had the opportunity to take a leave of absence and do big things. Both my trips to Everest required some creative work-arounds at my day job, banking vacation time, initially. There are all sorts of really cool adventures that can be done on a shorter scale too.

ANT GODDARD

ROAD-TRIPPED ALL OVER THE USA

I have a young kid and a pregnant wife, so I’m in a good position to tackle the regular excuse given by people that ‘the timing’s not right for adventure now, I’m too busy, life’s too complicated.’ It’s an interesting thought because it’s kind of similar to the dilemma of if/when to have kids. The timing will never be perfect. If you wait for the perfect time you’ll miss out. Mostly everything you think you can’t leave will still be there when you get back, and travelling gives you a lot of time to think about those complications and put them in perspective. There are very few things that are honest blockers to just getting out and having an adventure, no matter how large or small the adventure is. You may feel like there are a lot of ‘what-ifs’ preventing you doing something adventurous, but the scariest one in my mind has always been ‘what if I never go? What if I stay here forever?’