Полная версия

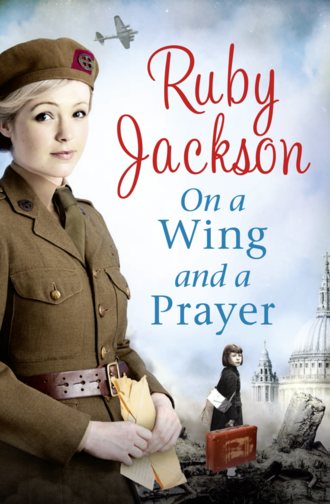

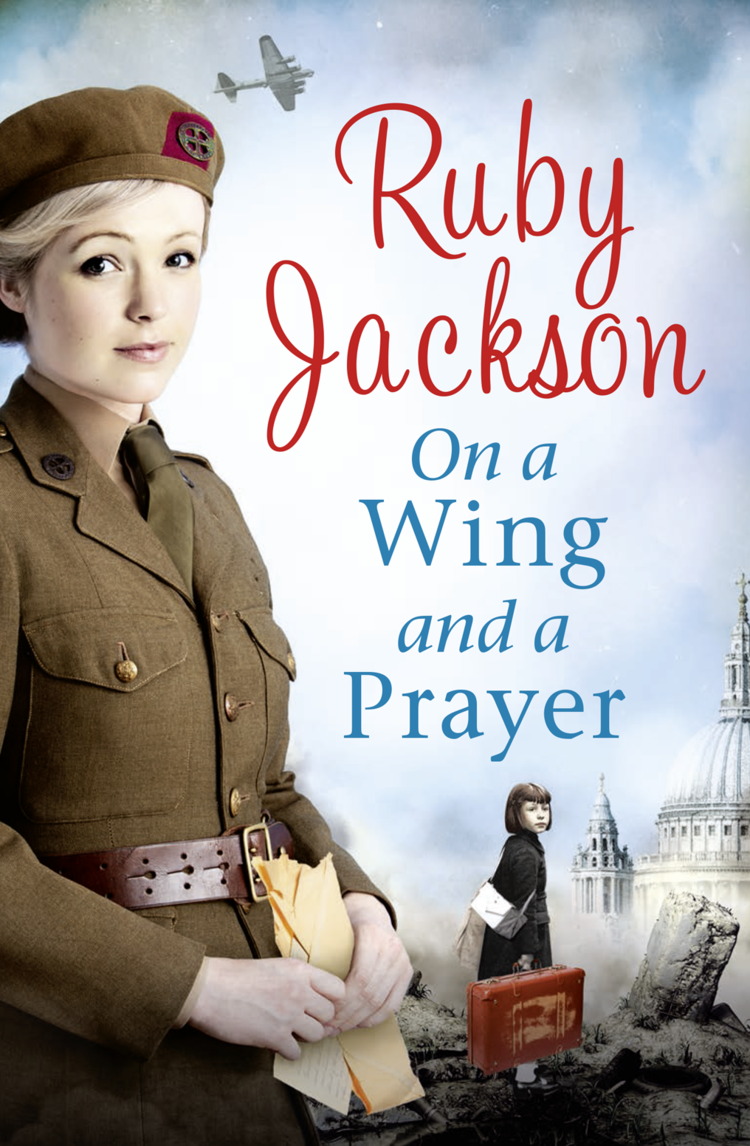

On a Wing and a Prayer

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by Harper 2015

Copyright © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover photographs © Johnny Ring (woman’s face); Colin Thomas (woman’s body); Popperfoto/Contributor/Getty Images (refugee girl); Shutterstock.com (letter, plane, suitcase, background)

Ruby Jackson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007506293

Ebook Edition © April 2015 ISBN: 9780007506309

Version: 2015-03-04

For Patrick O’Donnell and Dr Gary Colner with much love.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter ONE

Chapter TWO

Chapter THREE

Chapter FOUR

Chapter FIVE

Chapter SIX

Chapter SEVEN

Chapter EIGHT

Chapter NINE

Chapter TEN

Chapter ELEVEN

Chapter TWELVE

Chapter THIRTEEN

Chapter FOURTEEN

Chapter FIFTEEN

Chapter SIXTEEN

Chapter SEVENTEEN

Chapter EIGHTEEN

Chapter NINETEEN

Chapter TWENTY

Chapter TWENTY-ONE

Chapter TWENTY-TWO

Chapter TWENTY-THREE

Chapter TWENTY-FOUR

Chapter TWENTY-FIVE

Chapter TWENTY-SIX

Acknowledgements

Churchill Angels Ad

Wave Me Goodbye Ad

A Christmas Gift Ad

Churchill’s Angels Extract

W6 Ad

About the Author

Also by Ruby Jackson

About the Publisher

ONE

April 1942

‘It’s still so strange not to see Daisy sound asleep when I wake up early, Dad. The house is so quiet; when will it feel normal?’

Fred looked up from the front page of the Sunday paper. ‘When it is normal, pet, and your mum and me is hoping that’ll be soon. You’re an absolute godsend, our Rose. Kept your mum sane, you have.’ He went back to the lead article.

Rose stood quietly for a moment. Was this the time to say something, to say that she had been thinking for rather a long time that she needed a change, a chance to do something different? Could she say, ‘Remember in February when I had a bad head cold and didn’t go to evensong? Remember I caught Mr Churchill on the wireless, heard the whole thing, instead of catching just a bit as usual? I thought then – I’ve got to do something more, like Daisy and the others. When this war ends I’d like to have done something besides factory work’? She looked over at her father, relaxing in his armchair, his waistcoat for once unbuttoned, and decided not to disturb his one morning of relative peace and quiet.

She folded up the section of the Sunday paper she had been reading and almost slapped it down on the little table between them, inadvertently causing her father to jump. ‘Sorry, didn’t mean to do that. I’m off for a run. Nothing but doom and gloom in the Post this morning.’

‘Don’t forget Miss Partridge is taking her Sunday dinner with us – suppose we’ll have to call it “lunch” since it’s Miss Partridge – so don’t be late.’

Rose promised she wouldn’t be and, after changing her ‘going to church clothes’ for something suitable for running, she hurried away. Effortlessly, she jogged out of the town, past houses where heavily laden and sweetly scented lilac trees leaned over garden walls, tantalising passers-by with their perfume; past Dartford Grammar School, where she pretended not to see the enormous reserve water supply tank, which had been installed the year the war broke out as one of the many preparations for conflict. Would an enemy aircraft bomb it and flood the many lovely gardens in this part of the town? She hoped not. Since May of the year before, England had been experiencing a lull in the bombing raids from Germany and from the closer German bases in occupied Holland and France. But the worst part of a lull was that one never knew when it would end. In some ways this uncertainty was worse than nightly attacks. At least then people knew what to expect.

Rose changed direction to run through Central Park, formerly a favourite meeting place for local residents, especially on Sundays when families strolled among the flowerbeds. These days anxious parents preferred to stay at home rather than take a Sunday walk with one eye always on the sky and ears straining for the threatening sound of aircraft. Out of the park she ran, further and further into the countryside, now carpeted with spring flowers. She wondered if she had ever seen such stretches of golden buttercups; they were everywhere. Who could not feel happy just by seeing them? Fruit trees, too, showed off their mantles of pink or white blossom as they swayed in the gentle breeze. Who could believe that this glorious garden could possibly be a small part of a huge battlefield?

Rose began to run towards the river, revelling in the feeling of absolute freedom, enjoying stretching her long legs. She stopped, not because she was tired or stiff but because she wanted to stand still and breathe in the clear air. How absolutely beautiful it was. Everything was perfect. The blue sky was decorated with the remains of white vapour trails, showing where aircraft had passed. In the fields below and around her, green shoots were poking up through the soil and, some distance away, untethered horses were grazing. Smiling, Rose pretended that there was no war; there had never been a war and all was well with the world. She decided to run as far as Ellingham ponds, those little man-made pools that had been created when gravel and sand quarrying had stopped just before war had broken out. Horses had drunk from them; migrating birds or local wildfowl had nested there. The ponds were hardly objects of beauty now: every one was camouflaged with wire netting on a floating wooden frame, so that German airmen, sent to destroy the nearby Vickers munitions works, could not use reflections from the water as an aid to navigation.

Eventually she came to a halt, remembering that Miss Partridge was coming to Sunday dinner. Heavens, being late will certainly spoil a perfect Sunday, she thought as she began to trot slowly back along the way that she had come, and I do want to see Miss Partridge.

She reached the rather rough road that wound its way across the area, and was about to quicken her pace when she heard the sound of a speeding motorbike. It sounded as if it was on this country pathway. What an odd place to ride a motorbike, Rose thought as she jumped off the pathway and onto the wide grass verge.

Rose’s older brothers had taught her to drive before she left school at the age of fourteen, and she was accustomed to delivering groceries in the family van, but their parents had never allowed either of their twin daughters to ride a motorcycle. ‘They’re too heavy for girls,’ Sam, their eldest brother, had agreed. ‘If you can’t lift it, you shouldn’t be riding it.’ Nothing the girls had said had persuaded him to change his mind.

The roar of the engine grew louder and closer. Rose moved further back on the verge, noting, with growing concern, both the poor surface of the road and the sound of the accelerating bike. Before she could think another thought or move a muscle, the bike was there and then…was gone.

‘Wow. Fantastic, what a speed, lucky—’ Rose began aloud, just as she heard a screech of brakes, followed by a thud. She listened but there was nothing but a terrifying silence.

For a fraction of a moment, she felt rooted to the spot, but the adrenalin lifted her out of the almost trance-like state and Rose Petrie, former junior sports champion, began to run. She was round the corner in moments. The motorbike was lying on its side across the pathway. Her stomach lurched in horror as she saw the driver pinned underneath. Rose kneeled down beside the machine and tentatively examined the unconscious man. How young he was, and how very, very still. His eyes were closed and there was severe grazing on one side of his jaw; blood was seeping from a wound in his forehead and mixing horribly with the dirt and gravel on his face.

Rose had no idea if he was alive or dead. She remembered her brother’s words – ‘If you can’t lift it, you shouldn’t be riding it’ – and wondered if it would even be wise to attempt to lift the machine off the young man’s body. Should she try somehow to clean his poor face? Water? In the wonderful films she had seen with her sister and their friends, the wounded hero was always given a sip of water. If she ran back to one of the ponds perhaps she could manage to wet a cloth, but she had no cloth. She looked again at the motorcycle, which was possibly crushing something important while she hesitated. Rose seemed to remember that any implement sticking into the body of an injured person should not be removed until qualified medical personnel were on hand, but what was she supposed to do with a machine that might well be crushing this man to death?

Thank God, Rose thought as she felt a faint pulse in the neck. Could he hear her if she spoke, and would that help him? ‘I’m going to try to move your bike,’ she said as calmly as she could. Oh God, what if I drop it back onto him? ‘I’m really very strong,’ she continued, hoping against hope that her low voice was reaching him, perhaps giving him some comfort. ‘I work in a munitions factory and lift machinery every day. You wouldn’t believe how heavy some of that stuff is.’

There was no response and so Rose stood up, took a deep breath, bent down, grasped the body of the bike firmly, and, having assessed in which direction to move, began to lift. The trapped rider groaned. He’s alive, he’s alive. I can do this. In another moment she had the bike on the grass verge. She wanted to fall down beside it, as every muscle in her well-toned body seemed to be complaining, but instead she looked for something with which to wipe the blood from his face.

Why did I change? She was wearing only a shirt and her shorts. Then she heard a voice, faint but clear.

‘Help me.’

Immediately she was back on her knees beside the injured man. ‘I’m going for help,’ she said. ‘I wish I could stay with you but there’s no one else here.’ She was pulling her shirt out of her shorts. Desperately she tried to tear off the bottom but the material resisted.

Rose looked around and her eyes lit up as she saw a large shard of glass from the broken headlamp. She picked it up and feverishly sawed at the shirt. At last there was a tear, which allowed her to rip it apart.

Praying that it was clean, she folded it and gently wiped the blood from the man’s face. ‘I wish I could do more for you but I’ll get help…’

The whisper was so faint that she had almost to put her ear to his damaged face. ‘Dispatch. Pocket. Urgent…Take.’

Again Rose looked round, hoping desperately that someone – anyone – was within hailing distance. No one.

She felt a touch on her hand. ‘Please.’

‘Of course, I’ll do what I can.’ With a hand now marked by his blood she tried the pocket of his leather jacket. Nothing. ‘It’s a dispatch. An inside pocket. Do you have…?’

His eyes blinked as if answering her. Rose reached inside his jacket, hoping that she was doing no damage to his poor body. There was a pocket, and inside was a fairly thick envelope. ‘Got it,’ she said. ‘I’ll run for help and then deliv—’

The eyelids fluttered again and the voice was fainter than before. ‘Urgent. Please.’

‘I’ll do it. Trust me. I’ll get you some help. Trust me,’ she repeated. ‘I’ll deliver your letter and I will bring help.’ As she spoke the last words she was already running. She had not run competitively since she was a schoolgirl, but she was fit and well. She tried to forget the injured, possibly dying dispatch rider, and the message that seemed to be burning a hole through her shirt. She had read the word on the front. ‘SILVERTIDES’. She knew the name only because she had occasionally delivered tea to the kitchen door of the great house. It was at least three miles away and she had a single mode of transport – her long legs.

Rose kept going. As she ran she remembered the words of her coach from those long-ago school days. ‘Long and longer strides for the first twenty paces; then accelerate until you think you can’t go any faster. Relax facial muscles.’ She almost flew, her long stride eating up the uneven ground. She tried not to think of the letter she was carrying, or the dispatch rider who had insisted that he be left, possibly to die, in order that the dispatch might reach its destination. The young man was in the military and was obviously about the same age as her brother Phil.

Twenty-three is too young to die, she thought fiercely, remembering the loss of her brother Ron, who had been even younger when he had given his life for his country.

‘Empty your head, girl, empty your head,’ came the order from the long-ago voice, and obediently Rose forced herself to concentrate on nothing but finishing the race.

She ran as she had never run before, oblivious of her screaming muscles, her labouring breath, her tears. Heel, outside of foot, rock off with the toes, over and over again; push with your ankles, drive with your elbows. For a moment she was in a bubble as she pulled remembered advice up from her subconscious, which helped her think only of technique and not of injured dispatch riders or important messages.

Ahead stood the gates of Silvertides Estate. With her last ounce of energy she reached them, clung to the bars to prevent her body sliding, exhausted, to the ground, and pressed the bell.

‘Don’t fuss, Mum, it was no more than a cross-country run.’

Rose had had a refreshing bath and was now sitting in the scrupulously tidy front room, not the kitchen, so seriously had her parents taken her story of the afternoon’s events. Of course she had been much too late for Sunday dinner and was now pressingly aware of growing hunger.

‘Quite an adventure, our Rose, but your mum and me think you’re making light of it.’

‘’Course not, Dad. Only sorry I missed Miss Partridge.’

‘She said the same about you, love, but she’d promised to do geometry or some other maths subject with George – sharp as a tack is our George.’

Delighted to have young George Preston’s prowess become the subject of discussion, Rose congratulated her father again for taking in the orphaned youngster, who had initially caused the family a great deal of bother, culminating in vandalism and an attack that had put her twin sister, Daisy, in hospital.

But Fred had had years of experience in dealing with daughters who did not want to be the focus of his attention. ‘Come on, Rose. Rose ran, Rose saw accident, Rose helped injured rider, Rose delivered letter. Rose came home. There has to be more to it than that.’

‘Aw, Dad,’ moaned Rose, using exactly the tone of voice she had used as a disgruntled child, ‘he was speeding on a poor surface and a pothole caught the front tyre. He and the bike went up in the air – I think, I didn’t see it – and the bike landed on top of him. He asked me to deliver his dispatch and I did. Possibly I spoke to a butler sort of person, quite grand and with a posh voice, but he said not to worry, it was in their hands. I sat in a lovely room and a maid brought me tea; they’ll have got an ambulance…can’t be sure.’

Is he alive? Did they find him? They had promised to go immediately and they said they would get him a doctor.

A long-ignored memory surfaced. This was not the first time she had run for help. She had tried to black out all memory of that day on Dartford Heath, when Daisy had stayed beside two unbearably sad, dead bodies, and Rose, the faster runner, almost traumatised by shock and horror, had conquered her threatening hysteria and run for help.

‘Didn’t want to warm it too quick, Rose; nothing worse than dried-up food. Eat that up and then off to bed with you or you’ll never do your shift tonight.’ Her mother had come in from the kitchen at just the right moment, for Rose wanted to be left alone to think.

Sitting in an armchair in the front room with a plate of food in her hands took her straight back to childhood. Unwell? Unhappy? Either situation could be mended by sitting in a comfortable chair in the front room, eating a plate of Mum’s best stew. Not that this stew could measure up to the ‘before this dratted war’ stews; far more vegetables than meat – thank goodness carrots were not rationed – and a gravy Mum was near ashamed of. But so far the Petrie family had managed to avoid tinned stew. ‘Can’t be sure what’s in it,’ muttered Flora as she arranged the tins on their grocery shop shelves.

As she ate her lunch, Rose could remember nothing but the face of the dispatch rider and the feel of the gates at Silvertides as her exhausted body collapsed against them. Maybe it would all come back tomorrow. She wondered if she would ever find out about the injured rider. She knew enough about dispatch riders to realise that she would never learn what was in the so-vital letter. But it had to be really important. His face swam before her tired eyes and his voice whispered, ‘Urgent, please.’

I tried, she thought to console herself. I hope it was enough.

Two days later Rose was standing at her workbench on the factory floor. She was dirty and hungry and very, very tired. More than anything she longed for the shift to be over so that she could go home.

Rose’s shift supervisor appeared at her bench. ‘Petrie, got a minute? Boss wants you in his office.’

‘What’s wrong, Bill?’ Rose could think of no reason for a summons to the office.

‘He’ll tell you hisself and that’ll save me guessing, won’t it?’

Rose straightened up, took off her overall and the scarf that covered her hair, and walked off to the office, where she hesitated before knocking on the door.

‘You sent for me, Mr Salveson,’ she said, noting that as well as her boss and his secretary there was a second man in the room.

‘Come in, Rose. Mr Porter here would like to talk to you.’

Vaguely Rose felt that she knew the second man but could not place him. ‘I don’t understand, Mr Salveson.’

‘The local newspaper would like to talk to you, Miss Petrie, about your wonderful action in delivering the dispatch for the gallant boy who died trying to do his duty.’

Rose was speechless. The secretary saw the colour drain from her face and shouted in time for Mr Salveson to catch Rose before she fell to the floor. He lowered her into a chair and gestured to his secretary to fetch a glass of water, which he held to Rose’s lips.

She pushed it away. ‘Dead? He died?’

‘Yes, one of our stringers heard about it. The housekeeper at Silvertides told us how you ran with it. Seems his lordship had to go back to London before he could talk to you.’

Rose forced herself to stand up. ‘I’d like to go home now, Mr Salveson.’

‘We need an interview,’ said the reporter.

‘No,’ said Rose quietly, and looked at her employer.

‘Are you sure, Rose? People should hear about your courage.’

Courage? What courage had she needed to run a few miles with a letter? The boy, the dead boy, had had courage. ‘I won’t talk to the press, Mr Salveson, and the hooter’s gone.’

‘You heard her, Porter. Miss Petrie doesn’t seek publicity. I’ll drive you home, Rose. I can see you’ve had a bit of a shock.’

‘No, thank you, Mr Salveson. I’ll be fine with Stan Crisp. He’ll see me home.’

The disgruntled reporter left angrily and Rose went to catch her friend, Stan, before he headed off in the opposite direction. Really she wanted to be alone, but she could not be sure that the reporter would not follow her. If he did, she knew that Stan would not allow him to bother her. She did not tell him the whole truth, merely that she felt faint and would feel better if he was with her.

She always felt better when Stan was there.

TWO

May 1942

‘Stan, won’t you please come to the spring dance with me?’

Stan looked across the table at Rose and sighed.

‘Stan?’ she persisted unhappily.

‘Yes? Sorry, Rose, I thought you were going to ask someone else. Charlie’s a good dancer. Why don’t you ask him?’

‘I have asked, and everyone is either working that night or has already got a partner.’ She looked down at her hands, afraid to meet his eyes. ‘Why do none of them ever ask me out?’ She smiled then, thinking that she might have found the answer. ‘Is it because they think we’re an item?’

Rose, Daisy and Stan had started school on the same day and had been friends ever since. Rose and Stan had always been particularly close, and Stan’s grandmother, with whom he had lived since his parents had died in a flu epidemic, always referred to Stan and Rose as the perfect couple.

‘Now that we’re grown up, we’ll have to ask your granny to stop matchmaking.’

Stan looked around the room, as if hoping he might find an answer to her question written on one of the walls of the ancient tavern. He straightened his backbone. ‘It’s not Gran, Rose. Can I tell you the truth?’

‘I’ve got bad breath? For goodness’ sake, Stan, what is it?’

‘You scare everyone to death, pet, simple as that. Blokes don’t want to be second best – all the time.’

‘Scare everyone, me? How? And if I do scare everyone,’ she said, her voice heavy with sarcasm and throbbing with hurt, ‘why don’t I scare you?’ She stood up as if to leave.

‘Sit down, Rose,’ said Stan gently, and he pulled in her hand. ‘Maybe I should have said something years ago, but I like you just the way you are, and…’ he hesitated for a moment and then jumped in, ‘more importantly, I know that the right man for you will love you just as you are.’