Полная версия

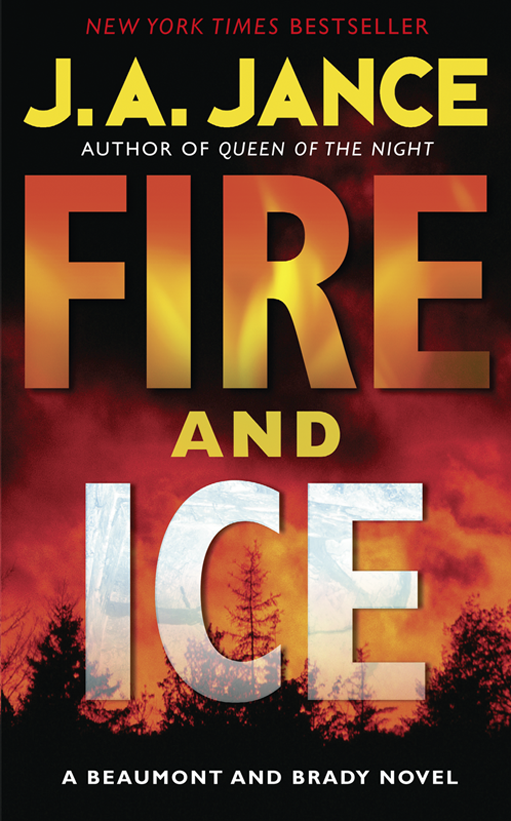

Fire and Ice

J. A. JANCE

Fire and Ice

Contents

PROLOGUE

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

Also by J. A. Jance

Copyright

About the Publisher

FIRE AND ICE

J. A. JANCE is the New York Timesbestselling author of the J. P. Beaumont series, the Joanna Brady series, the Ali Reynolds series, and three standalone thrillers. Born in South Dakota and brought up in Bisbee, Arizona, she lives with her husband in Seattle, Washington, and Tucson, Arizona.

www.jajance.com

For Larry Dever and Ken Wallentine, the real deals

And for Hal Witter, the real deal, too

November

DRIVING EAST on I-90, Tomas Rivera was surprised to see the snow spinning down out of a darkened sky in huge fat flakes that threatened to overwhelm the puny efforts of the 4-Runner’s hardworking windshield wipers. It was only the sixth of November. Snow this heavy didn’t often come to the Cascades so early in the season. Beyond Eastgate and North Bend electronic signs flashed a warning that traction devices were required in the pass.

The signaled warnings didn’t concern Tomas all that much. He was sure the stolen SUV’s four-wheel drive would get him through any snow on the roadway. Overworked cops would be so busy dealing with multiple fender-benders that he doubted they’d be on the lookout for stolen vehicles. It also seemed likely that it was too soon for the Department of Transportation to be doing avalanche control, but what if they were? What if he got stopped at the pass and had to wait for snowplows or ended up being stuck at the chain-up area for an hour or two? What if the girl on the floor in the far back of the SUV woke up suddenly and started making noises—thumping, bumping, or groaning? If people were standing around outside in the waiting area, he worried they might hear her or see her or start asking questions.

Despite the cold, Tomas found he was sweating. His armpits were soaked, and so were his hands inside the gloves, but he didn’t dare take them off.

“Wear gloves,” Miguel had warned him. “Whatever you do, wear gloves.”

Since it wasn’t a good idea to cross Miguel, Tomas wore gloves.

The poor woman had already been bound, presumably gagged, wrapped loosely in a tarp and dumped in the back of the 4-Runner when Miguel delivered the vehicle to him. Miguel didn’t say where she was from or why she was there, and Tomas didn’t ask. The less he knew about her, the better.

“Take her out in the woods and get rid of her,” Miguel had said. “There’s a full gas can in the back. Use that. Throw her out, pull her teeth, douse her with gasoline, and light a match. When you’re done, ditch the car somewhere far away. Understand?”

Tomas had nodded. He understood all right. And he understood what would happen if he didn’t. Tomas also understood Miguel and the men he worked with. They were rich and powerful, dangerous and ruthless. They were the kind of men who would kill you in a heartbeat, not with their two hands, of course, but they would have somebody around willing to do the dirty work. They’d hand it off to some poor dope who owed them and owed big; or to someone like Tomas who didn’t dare step out of line for fear of what would happen to him—or to his family.

Yes, Tomas thought. Someone just like me.

He understood what it meant to commit a mortal sin. If he didn’t get to confession and died, he’d go straight to hell. And if he didn’t do what he’d been told, he’d be living in hell. In a way, he already was. He had paid good money—money earned doing backbreaking, dangerous delimbing work out in the woods—to have Lupe and the boys smuggled across the border and brought north. But having paid a small fortune to Miguel’s coyotes didn’t mean Tomas and Lupe were home free. Miguel had made it clear that if Tomas didn’t do what was required of him, what might happen to Little Tomas and Alfonso would be worse than death. For the thousandth time Tomas wished he had left well enough alone. Things weren’t necessarily pleasant or comfortable in the little tin-roofed shack where Lupe and the boys had lived in Cuidad Obregon. But he’d had no idea about the real price of bringing his little family to the United States of America.

So Tomas kept driving. He turned off the freeway at Cabin Creek Road and headed off into the maze of National Forest roads that carried loggers and logging equipment off into the wilderness. That’s why Miguel had come looking for him to do this particular job. Tomas knew all those roads like the back of his hand—because he had driven them himself, ferrying crews in and out of the woods. With severe winter weather setting in, the logging crews were out of the picture for the time being—until the snow melted in the spring. Or summer.

Even though it made it hard to see, Tomas was grateful for the deepening snow. There would be no tire tracks left for the cops to trace. And no footprints, either. By morning, all tracks would be nothing more than slight dents. And in weather like this, no one would be out there watching, either. Only the dumbest of cross-country skiers would venture this far off the main roads.

As Tomas drove, he wondered what the woman had done that merited this death sentence, but he didn’t wonder too hard. That was Miguel’s business, not his.

Tomas stopped the SUV a mile or so short of Lake Kachess at a spot where yet another road wandered away from the one he was on. The intersection created a small clearing that was barely big enough for him to swing the 4-Runner in a tight circle without running the risk of getting stuck. When he turned off the engine, he was dismayed to realize that his prisoner was awake and moaning. Miguel had told him she was out for good, but clearly that wasn’t true.

Shaking his head, Tomas punched the button that unlocked the hatch, then got out and walked through swirling snow to the back of the vehicle. Opening the cargo bay, he reached in and grabbed the tarp-wrapped bundle. As he pulled it toward him, the woman inside struggled and tried to roll away. Grabbing for her a second time, his hand caught on what was evidently a cowboy boot, one that came off in his hand. It surprised him and bothered him somehow. He didn’t want to know she wore cowboy boots. He didn’t want to know anything about her at all.

When he finally had her free of the floorboard, he let her drop to the ground. The force of the fall knocked the breath out of her. For a brief moment she was quiet, then she started moving and struggling once more. The mewling sounds coming from under the tarp were aimed at him in a wordless plea that was clear enough.

“Please don’t do this. Please. Please. Please.”

Tomas didn’t want to do it, either. But it was too late to stop; too late to turn back. Tomas knew that if he failed or wavered, Lupe and the boys would become Miguel’s next target.

Tugging at the end of the tarp, he dragged her away from the road and into the shelter of a second growth tree. Then he went back for the tire iron. Several blows to the head from that rendered the woman senseless. He knew what he was supposed to do then. Tomas had the needle-nose pliers there in his pocket. But he also knew, as Miguel did not, that pulling her teeth was something Tomas could not do.

When his boys had lost their baby teeth—their loose baby teeth—Lupe had been the one who did the honors. The very idea of removing hers … Instead, he went back to the car and retrieved the gas can, poured the liquid over the now still tarp, and lit the match. He had to light more than one because it took more than one before the fumes finally ignited.

When they did, he moved back out of reach, crossing himself and uttering a quick prayer as the flames roared skyward through the swirling snow. In the flickering firelight, he looked down and noticed that while he was wrestling her out of the SUV, the cowboy boot had come to rest in the snow near the back bumper. Reaching down, Tomas picked it up and was about to toss it into the raging fire when he noticed that something had been taped to the instep. Peeling off the tape, he pulled out a small rectangular piece of stiff paper. It was blank on one side, but the other side revealed the smiling photo—a school photo, no doubt—of a dark-haired boy not that much older than his own sons.

Tomas looked back through the eddying snow. The tarp was fully engulfed now. So was the woman. The odor of burning gasoline was giving way to something else. He quickly tossed the boot into the flames, but for some reason he couldn’t bring himself to part with the photo. Slipping that into the pocket of his shirt, he turned and clambered back into the SUV.

As Tomas drove away, he wondered where and how he’d get rid of the 4-Runner. It had to be somewhere far away from surveillance cameras. He couldn’t afford to be seen anywhere near it, and not just because it was a stolen vehicle.

Now it was a matter of life and death—his as well as hers.

MARCH

LAKE KACHESS

KEN LEGGETT wasn’t what you could call a warm and fuzzy guy. For one thing, he didn’t like people much. It wasn’t that he was a bigot. Not at all. It wasn’t a matter of his not liking blacks or Hispanics or Chinese—he disliked them all, whites included. He was your basic all-inclusive disliker.

Which was why this solitary job as a heavy-equipment operator was the best one he’d ever had—or kept. In the spring he spent eight to ten hours a day riding a snowplow and uncovering mile after mile of forest road that logging companies used to harvest their treasure troves of wood from one clear-cut section of the Cascades after another.

Once the existing roads were cleared, he traded the snowplow for either a road grader, which he used to carve even more roads, or a front-end loader, which could be used to accumulate slash—the brush and branches left behind after the logs had been cut down, graded, and hauled away.

As long as he was riding his machinery, Ken didn’t have to listen to anyone else talk. He could be alone with his thoughts, which ranged from the profound to the mundane. Just being out in the woods made it pretty clear that God existed, and knowing his ex-mother-in-law, to say nothing of his ex-wife, made it clear that the devil and hell were real entities as well. Given all that, then, it made perfect sense that the world should be so screwed up—that the Washington Redskins would probably never win the Super Bowl and that the Seattle Mariners would never win the World Series, either.

The fact that Ken liked the Mariners was pretty self-explanatory. After all, he lived in North Bend—outside North Bend, really—and Seattle was just a few miles down the road. As for why he loved the Redskins? He’d never been to Washington—D.C., that is. In fact, the only time he’d ever ventured out of Washington State had been back in the 1980s, when his then-wife had dragged him up to Vancouver, B.C., for something called Expo. He had hated it. It had rained like crazy, and most of the exhibits were stupid. If he wanted to be wet and miserable, all he had to do was go to work. He sure as hell didn’t have to pay good money for the privilege.

As for the Redskins? What he liked about them most was that they hadn’t bowed to public opinion and changed their name to something more politically palatable. And when he was watching football games in the Beaver Bar in North Bend, he loved shouting out “Go, Redskins!” and waiting to see if anyone had balls enough to give him any grief over it. When it came to barroom fights, Little Kenny Leggett, as he was sometimes called despite the fact that he was a bruising six-five, knew how to handle himself—and a broken beer bottle.

So here he was sending a spray of snow flying off the road and thinking about the fact that he was glad to be going back to work. Early. A whole month earlier than anyone had expected. When winter had landed with a knock-out punch early in November, everybody figured snow was going to bury the Cascades with record-shattering intensity. The ski resorts had all hoped for a memorable season, and that turned out to be true for the wrong reason—way too little snow rather than too much.

That first heavy snowfall got washed away by equally record-shattering rains a few days later. For the rest of the winter the snow never quite got its groove back and had proved to be unusually mild. It snowed some, but not enough for skiers really to get out there. And not enough for the bureaucrats to stop whining about it, either. In fact, just that morning, on his way to work, Ken had heard some jerk from the water department complaining that the lack of snowfall and runoff might well lead to water rationing in the Pacific Northwest before the end of summer.

Yeah, Ken thought. Right. That makes sense, especially in Washington, where it rains constantly, ten months out of twelve.

Ken glanced at his watch. The switch to daylight saving time made for longer afternoons, but it was nearing quitting time, and that meant he was also nearing the end of that day’s run. His boss wasn’t keen on paying overtime, and Ken wasn’t interested in working for free, so he needed to be back at the equipment shed by the time he was supposed to be off duty.

It was a long way back—a long slow way—and the thermos of coffee he had drunk with his lunch had run through the system. After turning the plow around in a small clearing, he set the brake. Then, shutting off the engine, he clambered down and went to make some yellow snow.

After the steady roar of equipment, the sudden stillness was a shock to his system. He knew that old saying about if a tree falls in the forest and nobody hears it … He wondered sometimes about what happened if you took a leak in the woods and no one heard you or saw you, did it exist? Chuckling at that private joke, he headed for a tree that was a few feet off the road to do his business. Better here where there was little chance of being seen. Close to civilization, somebody might be out there. Ken didn’t exactly think of himself as shy, but still …

Spring was coming. The snow had melted away completely in some spots, but under the trees it was still thick enough. Once he was out of sight of the road, he spotted what appeared to be a small boulder sticking up out of the snow. He unzipped and took aim at that. As the stream of steaming yellow urine hit the rock, the remaining snow melted away and a series of odd cracks became visible in the rock’s surface. Squinting, Ken bent to take a closer look. Only after a long moment did what he was seeing finally register. When it did, the horrible realization hit him like the surge of a powerful electric shock. That boulder wasn’t a boulder at all. It was a skull, a gaping human skull, sitting at an angle, half in and half out of a batch of melting yellow snow.

Staring at the awful visage in astonishment, Ken staggered backward, all the while trying desperately to zip up his pants as he went. Unaware of where he was going, he stumbled over something—a root, he hoped—and fell to the ground. But when he looked back to see what had tripped him, he realized that it wasn’t a root at all. He had stumbled over a length of bone that his fleeing footsteps had dislodged from a thin layer of melting snow.

That was when he lost it. With a groan he ducked his head and was very, very sick. At last, when there was nothing left to heave, Ken Leggett wiped his mouth on his sleeve and lurched to his feet. With a ground speed that would have astonished his old high school football coach, Ken headed for the safety of his snowplow. Once inside, he locked both doors and then leaned against the steering wheel, shaking from head to toe and gasping for breath.

His first thought was that he’d just forget about it and let someone else find it later—much later. Ken didn’t like cops. He wasn’t good with cops. And if he reported finding a body, what if they thought he was somehow responsible? But then he managed to pull himself together.

What if this was my brother or my son? Or my sister or daughter? he thought. I wouldn’t want whoever found them to walk away and leave them. Straighten up, he told himself. Have some balls for once and do the right thing.

He reached over to the stack of orange construction cones he kept on the snowplow’s muddied floorboard. He pulled one of those loose and then, after opening the window, dropped it outside. It landed right in the middle of the footprints he’d left in the snow as he leaped back into the vehicle. At least this way he’d be able to find the spot again; he’d be able to bring someone here.

Steeling himself for that ordeal, Ken made himself a promise. Once he got through with the cops, he would hit the Beaver Bar and stay there until he was good and drunk. The best thing about the Beave was that he could walk home from there. Ken Leggett already had a lifetime’s worth of DUIs. He had paid all those off now, and he sure as hell didn’t need another one.

He started the snowplow then and put it in gear. Halfway back to the equipment shed, he stopped and checked to see if he had a signal on his cell phone—only half a bar but enough. His hands still shook as he dialed the number.

“Washington State Patrol,” the 911 operator answered. “What are you reporting?”

“A body,” Ken replied. His voice was shaking, too, right along with his hands. “I just found a dead body out here in the woods.”

“You’re certain this person is deceased?” the operator asked.

“He’s dead, all right,” Ken answered. “As far as I can see, all that’s left of him is bones.”

March

I AM NOT a wimp. Maybe that sounds too much like Richard Nixon’s “I am not a crook,” but it’s true. I’m not. With twenty-plus years at Seattle PD, most of it on the Homicide Squad, and with several more years of laboring in the Washington State Attorney General’s Special Homicide Investigation Team, I think I can make that statement with some confidence. Usually. Most of the time. Right up until I got on the Mad Hatter’s Tea Party ride at Disneyland with my six-year-old granddaughter, Karen Louise, aka Kayla.

She had been in charge of the spinning. She loved it. I did not. When the ride ended, she went skipping away as happy as can be toward her waiting parents while I staggered along after her. Over her shoulder I heard her say, “Can we go again?” Then, stopping to look at me, she added, “Gramps, how come your face is so green?” Good question.

When Kayla was younger, she used to call me Gumpa, which I liked. Now I’ve been demoted or promoted, I’m not sure which, to Gramps, which I don’t like. It’s better, however, than what she calls Dave Livingston, my first wife’s second husband and official widower. (Karen, Kayla’s biological grandmother, has been dead for a long time now, but Dave is still a permanent part of all our lives.) Kayla stuck him with the handle of Poppa. As far as I’m concerned, that’s a lot worse than Gramps.

But back to my face. It really was green. I was having a tough time standing upright, and believe me, I hadn’t had a drop to drink, either. By then, though, Mel figured out that I was in trouble.

Melissa Majors Soames is my third wife. That seems like a bit of a misnomer, since my second wife, Anne Corley, was married to me for less than twenty-four hours. Our time together was, as they say, short but brief, ending in what is often referred to as “suicide by cop.” It bothered me that Anne preferred being dead to being married to me, and it gave me something of a complex—I believe shrinks call it a fear of commitment—that made it difficult for me to move on. Mel Soames was the one who finally changed all that.

She and I met while working for the S.H.I.T. squad. (Yes, I agree, it’s an unfortunate name, but we’re stuck with it.) Originally we just worked together, then it evolved into something else. Mel is someone who is absolutely cool in the face of trouble, and she’s watched my back on more than one occasion. And since this whole idea of having a “three-day family-bonding vacation at Disneyland” had been her bright idea, it was only fair that she should watch my back now.

She didn’t come racing up to see if I was all right because she could see perfectly well that I wasn’t. Instead, she went looking for help in the guise of a uniformed park employee, who dropped the broom he was wielding and led me to the first-aid station. It seems to me that it would have made sense to have a branch office of that a lot closer to the damned teacups.

So I went to the infirmary. Mel stayed long enough to be sure I was in good hands, then bustled off to “let everyone know what’s happening.” I stayed where I was, spending a good part of day three of our three-day ticket pass flat on my back on an ER-style cot with a very officious nurse taking my pulse and asking me questions.

“Ever been seasick?” she wanted to know.

“Several times,” I told her. I could have added every time I get near a boat, but I didn’t.

“Do you have any Antivert with you?” she asked.

“I beg your pardon?”

“Antivert. Meclizine. If you’re prone to seasickness, you should probably carry some with you. Without it, I can’t imagine what you were thinking. Why did you go on that ride?”

“My granddaughter wanted me to.”

She gave me a bemused look and shook her head. “That’s what they all say. You’d think grown men would have better sense.”

She was right about that. I should have had better sense, but of course I didn’t say so.

“We don’t hand out medication here,” she said. “Why don’t you just lie there for a while with your eyes closed. That may help.”

When she finally left me alone, I must have fallen asleep. I woke up when my phone rang.

“Beau,” Ross Alan Connors said. “Where are you?”

Connors has been the Washington State Attorney General for quite some time now, and he was the one who had plucked me from my post-retirement doldrums after leaving Seattle PD and installed me in his then relatively new Special Homicide Investigation Team. The previous fall’s election cycle had seen him fend off hotly contested attacks in both the primary and general elections. With campaigning out of the way for now, he seemed to be focusing on the job, enough so that he was calling me on Sunday afternoon when I was supposedly on vacation.

“California,” I told him. “Disneyland, actually.”

I didn’t mention the infirmary part. That was none of his business.

“Harry tells me you’re due back tomorrow.”

Harry was my boss, Harry Ignatius Ball, known to friend and foe alike as Harry I. Ball. People who hear his name and think that gives them a license to write him off as some kind of joke are making a big mistake. He’s like a crocodile lurking in the water with just his eyes showing. The teeth are there, just under the surface, ready and waiting to nail the unwary.