Полная версия

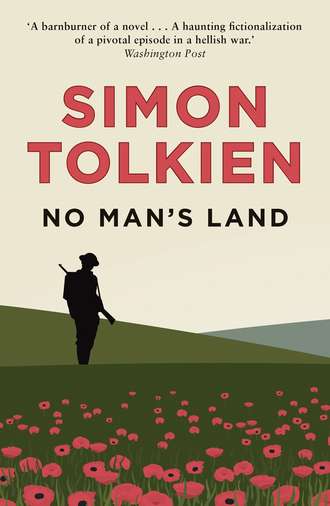

No Man’s Land

Afterwards he crawled forward, indifferent to the madness all around him, and covered her body with his, even though he knew that he had failed her and that it was too late to redeem his fault.

Chapter Two

Daniel broke the news to his son in a flat, matter-of-fact way. He told him that he was responsible and that none of it would have happened if he’d been a better husband and a better father. And when Adam rushed away up the stairs he didn’t follow him but just went out the back door and stood with his hands thrust deep into his pockets under the empty washing line, gazing up at the stars with dry, unblinking eyes.

Adam buried his face in his pillow, turning, winding the sheet around his body. And from outside he could hear a cry, human but inhuman, coming up from down below. Falling and rising on unconscious breath, it was the cry of a broken spirit, someone alive who could not bear to be alive. He heard it again five years later in the trenches in France on the night after battle and recognized it for what it was.

He slept, stupefied by exhaustion, and woke up in the early light and for a moment didn’t know. And when he did, he pulled on his clothes quickly. He had to keep moving. Across the landing, his father was asleep, lying face down on the bed in all his clothes. His shoes hung over the edge and Adam thought of untying them, but he couldn’t. It was his mother’s bedroom too and he couldn’t bear to go in there. In fact he couldn’t bear to be in the house. Downstairs her sewing machine and her needlework, her spectacles and her apron, all spoke of her continuity, but her coat missing from the stand by the door told a different story. She was gone; she wasn’t coming back. And each time he remembered, it was like the twist of a sharpened knife in a raw, open wound.

He went out into the street. But now he saw it with new eyes: it was a tawdry show, a mockery of life. Cabbage stalks and refuse in the gutter; horse manure; a dead cat. And the uncertain sympathy on people’s faces made him remember when all he wanted to do was forget. He walked on quickly but aimlessly – anywhere to get away, and found himself outside the church his mother used to take him to. He gazed up at the high tapering spire pointing like a compass needle towards heaven and wondered if it was a meaningless gesture. Was there anyone up there? If there was, the God in the clouds wasn’t a loving God as his mother had said. Adam knew better now: God was more cruel and vengeful than even Father Paul could imagine. Adam shook his fist at God and turned away.

He was hungry; famished. He wanted to die but he was desperate to eat. He had two pennies in his pocket and bought some fish and chips and ate them standing up, gulping down the food like an animal. Afterwards he felt sick, but he also felt as if he’d made a choice – to stay alive.

A day passed and then another and he went with his father to the inquest. He sat at the back, forgotten at the end of a long grey bench, while a police sergeant described in a monotonous voice what had happened to Adam’s mother ‘on the fateful day’, as he called it, cradling his helmet in his hands as he talked, as though it was a baby. The sergeant said he wasn’t the horseman who had crushed the deceased, but that he’d had an excellent view of all that had occurred: the woman had run forward, giving the rider no chance to take evasive action. And then Adam’s father spoke too, saying over and over again that it was his fault; that he was the one responsible: ‘If I’d been at home like Lilian wanted, then she’d be alive now and this would never have happened.’ But the coroner couldn’t punish him; he didn’t even want to. It was an accidental death, a tragedy, and he extended his sympathy to the family as he released the body to them for burial.

Daniel was a broken man but on one issue he was adamant: he wouldn’t allow his wife’s crushed and mutilated body to come home. There would be no wake, no laying out, no chance for Adam to see what had really happened to his mother. He rejected his neighbours’ sympathy and their offers of help, and invited no one to the funeral, so that there was just Daniel and Adam and Father Paul’s curate at the graveside as the undertakers’ men dropped the small plain pine coffin down into the pit that the parish sexton had excavated out of the hard ground. Father Paul had made it quite clear that he considered himself far too grand for what was little better than a pauper’s funeral.

Most of the other families on the street belonged to funeral clubs, contributing a penny or two a week to guarantee a proper send-off when their time came. And, left to her own devices, Lilian would have liked to have done the same, but Daniel had refused to allow it. He hated the idea that the only thing the poor saved for was their deaths, as if that was all they had to look forward to. He had wanted better for his family and now the cost of even the cheapest funeral that the undertaker had been able to offer had left him almost destitute.

Every day he walked the streets looking for work and came home in the evening empty-handed. The building trade was always slow in winter and his work with the union had marked him out as a troublemaker. He knew he was getting nowhere but being out was better than being at home, trapped inside with his memories, and he needed time to think, to come to terms with his grief.

He met Adam in the evenings, sharing inadequate meals beside the cold hearth. The silence between them had become tangible, almost developing into an estrangement. Daniel knew he was failing his son when the boy needed him most, but he also knew that he had nothing to give. Not yet, not until he had worked out what to do.

Each day he went further, walking to forget his hunger, wearing out his boots as he tramped past miles and miles of windswept brick terraces until he reached unnamed places where tarred fences studded with nails and ‘No Trespass’ boards stopped him going on into wastelands strewn with broken glass, tin cans and ash. And there, on the borders of nowhere, he finally made a decision and turned for home.

Early the next day he took the last of his money from behind the loose brick beside the fireplace and told his son to pack his bag. He already had his own ready, sitting beside the front door on top of the final unopened letter from the landlord giving him notice to quit.

‘Where are we going, Dad?’ asked Adam.

‘Somewhere you’ll be safe until I come back for you.’

‘Where, Dad?’ Adam repeated his question, even though he thought he knew the answer. They had no close friends or relations in London and so there was only one place where his father could leave him behind.

Daniel bit his lip, unable to look his son in the eye.

‘It’s the workhouse, isn’t it? That’s where you’re taking me. You’re going to abandon me, just like you abandoned my mother.’ Adam’s voice rose, fear and rage finally overcoming the deference he always showed towards his father.

‘I didn’t abandon your mother,’ Daniel said.

‘Yes, you did. You admitted it at the inquest. I heard you – you said that if you’d stayed at home Mother would still be alive. But instead you had to have your stupid strike. The strike was what you cared about, not me or Mother.’

Tears were streaming down Adam’s face but he didn’t notice them. His words slashed at his father like the lashes of a whip and Daniel involuntarily stepped back, angered by his son’s unexpected attack. The blood rushed to his head and he was about to assert his authority and put the boy in his place, but then at the last instant he bit back on his words. Some sixth sense made him realize the importance of the moment – it was a crossroads in their relationship that could either drive them further apart or perhaps bring them back together.

‘You’re right,’ said Daniel, forcing himself to speak slowly; choosing his words carefully. ‘I put my politics before my family and I was wrong. And I have paid a terrible price—’

‘We have,’ Adam interrupted, throwing the words in his father’s face. Because words were not enough; he needed to feel that his father truly understood the crime he had committed. Without that there could be no forgiveness.

‘Yes, we have. And I promise you I won’t make the same mistake again, Adam. You are more important to me than any idea. I will never abandon you. Try to believe me …’ Daniel held out his hand to his son.

And the pent-up passion in Adam suddenly broke like a rush of water flooding through the falling walls of a broken dam. His grief for his mother, his fear for the future, his love for his father, came together in a wave of emotion that took him forward and into his father’s arms.

‘Get your things,’ said Daniel, releasing his son after a moment. ‘Leaving is only going to get harder the longer we stay here.’

But it wasn’t the house that was hard to leave; it was the street. Instinctively Adam knew that he wouldn’t be coming back, at least not for a long time, not until he’d become an older, different person revisiting childhood memories when they were no more than dust in the wind.

And as he followed his father down the road on that bright winter morning it all came back to him. The sepia lens through which he’d seen the world since his mother’s death dropped away and he saw the barefoot children running behind the water cart soaking their legs and feet in the spray as it rattled over the cobblestones; saw them dancing round the horse trough where he’d spent a hundred Sundays; saw them stop and wave goodbye as he reached the Cricketers on the corner and paused to look back one last time.

The golden rays of the rising sun glared back at Adam and his father from off the thick engraved glass in the pub’s window panes, and from somewhere inside they could hear an invisible woman singing a popular song to the accompaniment of the pub’s penny-in-the slot piano:

‘If I should plant a tiny seed of love

In the garden of your heart,

Would it grow to be a great big love some day?

Or would it die and fade away?’

She sang well, holding the melody, and Adam stopped to listen, but his father took his arm and pulled him forward.

‘We need to go,’ Daniel said, and Adam sensed the tautness in his father, saw the muscles working in his face. He seemed for a moment like a drowning man trying desperately to stay afloat.

It was a long walk through Highbury and up into Holloway where they went by the women’s prison: a dreadful building with blackened Gothic spires and high castellated walls surmounted by barbed wire. And the workhouse when they reached it was just as forbidding, although in a different way: long and grey and flat with rows of clean, closed windows running in a line under the stacks of smokeless chimneys, and above them a brick clock tower with a bell that mournfully tolled the hour just as they arrived outside the door.

The place terrified Adam – he remembered what his father had said about the workhouse in times gone by: it was the place where the poor were sent to die when they were no use to the rich any more; it was the house at the end of the world.

‘Please, Dad, don’t leave me here. Take me with you,’ he implored his father.

‘I can’t,’ said Daniel. ‘I don’t have the money to support us both. Not until I’ve got work. And you’ll be safe here.’

‘I don’t want to be safe; I want to be with you.’

‘You will be. I promise. But for now you’ve got to stay here and trust me. Can you do that, Adam?’ Daniel asked. He leant down, putting his hands on his son’s shoulders, trying to look him in the eye. But Adam kept his gaze on the floor: he hated his father just as much as he loved him at that moment. Finally, reluctantly, he nodded his head.

‘Good lad,’ said Daniel, straightening up. ‘I knew I could count on you.’ He reached out his hand and pulled the bell cord.

‘Listen, Adam, I’ve got to go now,’ said Daniel quickly. ‘The Guardians, the people who run this place, might cause problems if they see me here, but if you’re on your own they’ve got to look after you; so – goodbye. I’ll be back, I promise.’ He put his hand on his son’s shoulder and suddenly pulled him close in a tight embrace. And then, picking up his bag, he walked quickly away.

And for Adam there was no time to think. A wooden grating in the door was shot back and a pair of dark eyes looked out at him for a moment from above a thick moustache.

‘New?’ asked the voice of the otherwise invisible man.

Adam nodded, and there was a sound of bolts being drawn back and a key being turned in the lock. Adam wanted to run away. He felt that once inside, behind this thick iron door, he would never get out again. He hesitated, looking wildly up and down the street, and gave up. He had nowhere to go, no money in his pockets, and he had given his word that he would stay. If he left now his father might never find him when he came back. If he came back.

The porter was dressed in a blue serge suit with gold braids on the sleeves and collar. He looked pleased with himself; pleased with his uniform and with his elaborate military moustache curled up into tiny black spikes at the corners of his mouth. He towered over Adam, looking him up and down as if he was conducting a preliminary assessment, which perhaps he was.

‘All right then,’ he said eventually. ‘Follow me.’ And he set off at a brisk pace down a series of wide corridors with spotless linoleum floors and plain whitewashed walls. There was not a speck of dust anywhere. And all the doors they passed were shut; the porter’s thick bunch of keys jangled against his trousers as he walked and Adam imagined that he had individual keys for every one.

In the receiving ward Adam was told to take off his clothes by a male attendant who went through all the pockets, searching for contraband, before packaging them up in brown paper. And then he had to endure a bath in cold water and a badly executed haircut before he was allowed to get dressed again, this time in the workhouse uniform: a striped cotton shirt, ill-fitting trousers and a jacket made of some coarse fabric with ‘Islington Workhouse’ stitched above the breast pocket.

He felt tired suddenly and wanted desperately to sit down, but the attendant pushed him forward down yet another corridor and into a small windowless office where a grey-haired man with half-moon spectacles perched on the end of his nose was sitting behind a large kneehole desk from which he never seemed to look up. He asked Adam questions about his history and recorded the answers in a huge ledger, pausing frequently to dip his pen in the inkwell, and then listened without interruption to Adam’s account of how he had ended up at the workhouse door before writing the single word, ‘Abandonment’ in the ‘Reason for admission’ column.

‘What’ll happen to me?’ asked Adam. There was fear in his voice: each stage of the admission process had seemed to strip another layer of his identity away until he felt that there was almost nothing left.

‘Perhaps they’ll send you back to school, although you’re almost too old for that. The Guardians will decide,’ he told Adam.

‘When?’

‘At their next meeting,’ the grey-haired man laconically replied, and turned his attention to the next admission, an old man with his belongings tied up in a dirty red handkerchief, distraught because he’d just been separated from his wife of forty years. His protests fell on deaf ears. The Poor Law required separation of the sexes and in the workhouse the law was absolute.

It was a terrible place: everything was regulated – from the exact weight of stones required to be broken in the yard each day to the precise allowances of food for each inmate (Adam received six ounces of bread at supper, although he would have been entitled to eight if he had been a year older). The refectory vividly reminded Adam of the penny sit-up that his father had taken him to in what felt like another lifetime. The inmates sat in rows facing forward, eating their allotted portions in silence before the bell called them back to work.

Because of his age Adam was excused from stone-breaking and was instead put to work picking apart tarred ropes to make oakum that the shipyards used for caulking boats. After unravelling the rope into corkscrew strands, the inmates had to roll them on their knees until the mesh became loose and the fibres could be broken up into hemp. Soon Adam’s fingers became red and raw, so they looked like his father’s hands had sometimes used to look when he came back from work after using soda water to strip old paper from the walls of houses that his crew was refurbishing.

Throughout the day two old sallow-faced officials dressed in identical threadbare black suits walked up and down the aisles between the benches, watchful for any slacking. The inmates picked in silence and the overseers’ monotonous pacing of the hard boards was the only noise in the big windowless workroom in which all the light came from above through circular skylights set in the flat roof. And at the end of the day each worker’s oakum was weighed at a desk by the door; failure to pick the required quota was punished by a reduction in the malefactor’s food allowance. In this, as in all its rules and regulations, the workhouse was mindful of its legal duty to ‘provide relief that was inferior to the standard of living that a labourer could obtain without assistance’. The Guardians wanted to be quite sure that nobody in their right mind would choose this life if he could possibly avoid it.

At night the inmates slept side by side on flock-filled sacks in narrow unheated dormitories. There were men of all ages and boys all mixed together. Some screamed out in their sleep: unintelligible cries which kept Adam awake into the small hours. Lying on his back in the dark, he thought of his mother and then tried not to because it hurt to remember her when she was dead. But blocking her out of his mind made him feel guilty – it felt as though he was killing her a second time. He remembered what the children in his street said about the dead: touching them stopped you dreaming of them. That’s why the old midwife who lived above the Cricketers was paid to lay out the corpse; that’s why bereaved families stopped the clocks and kept candlelit vigils around the body while the neighbours came by and paid their respects. But Adam’s father had refused to do any of this. He’d refused to employ the midwife; he’d shut the door on his neighbours. And as a result Adam had never seen his mother dead; he’d never had the chance to say goodbye.

Adam blamed his father for his mother’s death and for abandoning him in the workhouse. He was angry with his father, angrier than he had ever been with anyone in his whole life, and yet he longed for his father to return and take him away as he’d promised. But he heard nothing. It was as if he had been forgotten, walled up and left to rot like the Frenchman in the iron mask in the story that his mother had read to him the year before from a book that she’d bought second-hand from the barrow man.

In the workhouse only the birds were free, able to escape. Adam looked up through the skylights in the workroom and saw them circling overhead and remembered an autumn evening years and years before when his mother had come and woken him. He was sleepy and she had carried him down the stairs and out of the door and pointed up into the misty sky where he could make out the shapes of hundreds of low-flying swallows, calling to one another as they flew over.

‘Where are they going?’ he’d asked.

‘To Africa where it’s warm. They’ll be back in the spring. Aren’t they wonderful, Adam?’ she’d said – and he thought for a moment that he could hear her voice in his head like a distant echo. The vividness of the unexpected memory jolted him – it seemed significant, as if his mother was communicating with him in some invisible way. Suddenly the hope that had been draining out of him ever since her death returned. And when Daniel arrived at the workhouse the next day with two third-class railway tickets in his hand, it was almost as if Adam was expecting him.

The destination was somewhere Adam had never heard of – a place called Scarsdale.

‘Where is it?’ he asked as they came out through the workhouse door into the early-morning sunshine.

‘In the north,’ said Daniel.

Adam saw his father was smiling, as though he didn’t have a care in the world, and it made him angry. ‘How far in the north?’ he asked.

‘A long way.’

‘Well, I hope it’s as far away as Australia,’ said Adam fiercely. ‘Because I never want to see this place again and I never want to remember that you put me here.’

‘I had no choice,’ said Daniel, biting his lip.

‘There’s always a choice,’ said Adam.

Daniel didn’t answer. He’d seen inside the workhouse and he felt ashamed of having left his son in such a place, and he also sensed obscurely that he didn’t have the same authority over him that he’d had before. The last weeks had changed Adam: he was no longer a boy even if he was not yet a man. Daniel had mixed feelings about the transformation: he mourned the past but he was also glad, knowing that Adam would need all the inner strength and independence he could muster to survive in the place where they were going.

They reached the end of the street and turned the corner and Adam didn’t once look back.

Chapter Three

The train left in the evening and Adam and his father waited on the platform under the huge vaulted roof of the station as the day turned to dusk and everything around them dissolved into a blue and grey mist of vapour and smoke, pierced here and there by the pallid glow of the tall arc lights. Across from where they were sitting, they could see the rich coming and going through the door of the first-class restaurant: tall men in frock coats with hats and gloves escorting ladies in narrow-waisted hobble skirts who minced slowly along, their heads almost invisible under elaborate feathered hats. They reminded Adam of the flamingoes that he had seen at the zoo years before, inhabitants of an unknowable world operating on principles entirely outside his understanding.

As the departure time approached the platform filled up and Adam felt his heart beating hard. He knew Euston from days spent in the shadow of the great arch, earning coppers loading and unloading luggage for cabbies at the roadside, but he had never been on a train. He had never been outside London.

He heard the locomotive before he saw it – the scream of its whistle, the screech of engaging brakes, the hiss of steam; and then emerging out of the great pall of smoke came the black-and-red engine, a breathing, snorting mammoth of incredible power. And suddenly there was a frenzy of activity: carriage doors opening and disgorging passengers all the way down the line; porters and guards shouting, holding back the pressing crowd.

‘Come on,’ said Daniel, picking up his bag, and Adam almost lost his father in a sea of shabby jackets and cloth caps but caught sight of him at the last moment waving from the running board. He pushed forward and felt his father’s hand on his, pulling him up into the train.

Inside the compartment they found seats, perched on the ends of two wooden benches, facing each other in the flickering gaslight. Doors slammed and the shouts of the people outside were stilled by the guard’s whistle as the train spluttered back into life and began to pull away from the platform, picking up speed as it headed north, running smoothly along steel viaducts built high above the poor streets where Adam had grown up.

He closed his eyes and thought again of his mother: the leaving of London felt like a betrayal, as if he was leaving her behind too, somewhere back there in the smoky darkness, deliberately severing his last connection with her forever. He knew he was being irrational – that she was gone already – but that didn’t help with the raw tearing emptiness he felt inside whenever he forgot she was dead and then suddenly remembered. He hated that he couldn’t think of her without pain. It made him angry, and he realized that he was angry with her too – because she was supposed to explain these things to him and now she couldn’t.