Полная версия

How to be Alone

This much of the evening was typically Alzheimer’s. Because children learn social skills very early, a capacity for gestures of courtesy and phrases of vague graciousness survives in many Alzheimer’s patients long after their memories are shot. It wasn’t so remarkable that my father was able to handle (sort of) my brothers’ holiday calls. But consider what happened next, after dinner, outside the nursing home. While my wife ran inside for a geri chair, my father sat beside me and studied the institutional portal that he was about to reenter. “Better not to leave,” he told me in a clear, strong voice, “than to have to come back.” This was not a vague phrase; it pertained directly to the situation at hand, and it strongly suggested an awareness of his larger plight and his connection to the past and future. He was requesting that he be spared the pain of being dragged back toward consciousness and memory. And, sure enough, on the morning after Thanksgiving, and for the remainder of our visit, he was as crazy as I ever saw him, his words a hash of random syllables, his body a big flail of agitation.

For David Shenk, the most important of the “windows onto meaning” afforded by Alzheimer’s is its slowing down of death. Shenk likens the disease to a prism that refracts death into a spectrum of its otherwise tightly conjoined parts—death of autonomy, death of memory, death of self-consciousness, death of personality, death of body—and he subscribes to the most common trope of Alzheimer’s: that its particular sadness and horror stem from the sufferer’s loss of his or her “self” long before the body dies.

This seems mostly right to me. By the time my father’s heart stopped, I’d been mourning him for years. And yet, when I consider his story, I wonder whether the various deaths can ever really be so separated, and whether memory and consciousness have such secure title, after all, to the seat of selfhood. I can’t stop looking for meaning in the two years that followed his loss of his supposed “self,” and I can’t stop finding it.

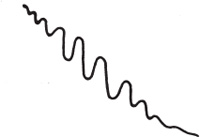

I’m struck, above all, by the apparent persistence of his will. I’m powerless not to believe that he was exerting some bodily remnant of his self-discipline, some reserve of strength in the sinews beneath both consciousness and memory, when he pulled himself together for the request he made to me outside the nursing home. I’m powerless as well not to believe that his crash on the following morning, like his crash on his first night alone in a hospital, amounted to a relinquishment of that will, a letting-go, an embrace of madness in the face of unbearable emotion. Although we can fix the starting point of his decline (full consciousness and sanity) and the end point (oblivion and death), his brain wasn’t simply a computational device running gradually and inexorably amok. Where the subtractive progress of Alzheimer’s might predict a steady downward trend like this—

what I saw of my father’s fall looked more like this:

He held himself together longer, I suspect, than it might have seemed he had the neuronal wherewithal to do. Then he collapsed and fell lower than his pathology may have strictly dictated, and he chose to stay low, ninety-nine percent of the time. What he wanted (in the early years, to stay clear; in the later years, to let go) was integral to what he was. And what I want (stories of my father’s brain that are not about meat) is integral to what I choose to remember and retell.

One of the stories I’ve come to tell, then, as I try to forgive myself for my long blindness to his condition, is that he was bent on concealing that condition and, for a remarkably long time, retained the strength of character to bring it off. My mother used to swear that this was so. He couldn’t fool the woman he lived with, no matter how he bullied her, but he could pull himself together as long he had sons in town or guests in the house. The true solution of the conundrum of my stay with him during my mother’s operation probably has less to do with my blindness than with the additional will he was exerting.

After the bad Thanksgiving, when we knew he was never coming home again, I helped my mother sort through his desk. (It’s the kind of liberty you take with the desk of a child or a dead person.) In one of his drawers we found evidence of small, covert endeavors not to forget. There was a sheaf of papers on which he’d written the addresses of his children, one address per slip, the same address on several. On another slip he’d written the birth dates of his older sons—“Bob 1–13–48” and “TOM 10–15–50”—and then, in trying to recall mine (August 17, 1959), he had erased the month and day and made a guess on the basis of my brothers’ dates: “JON 10–13–49.”

Consider, too, what I believe are the last words he ever spoke to me, three months before he died. For a couple of days, I’d been visiting the nursing home for a dutiful ninety minutes and listening to his mutterings about my mother and to his affable speculations about certain tiny objects that he persisted in seeing on the sleeves of his sweater and the knees of his pants. He was no different when I dropped by on my last morning, no different when I wheeled him back to his room and told him I was heading out of town. But then he raised his face toward mine and—again, out of nowhere, his voice was clear and strong—he said: “Thank you for coming. I appreciate your taking the time to see me.”

Set phrases of courtesy? A window on his fundamental self? I seem to have little choice about which version to believe.

IN RELYING ON MY MOTHER’S LETTERS to reconstruct my father’s disintegration, I feel the shadow of the undocumented years after 1992, when she and I talked on the phone at greater length and ceased to write all but the briefest notes. Plato’s description of writing, in the Phaedrus, as a “crutch of memory” seems to me fully accurate: I couldn’t tell a clear story of my father without those letters. But, where Plato laments the decline of the oral tradition and the atrophy of memory which writing induces, I at the other end of the Age of the Written Word am impressed by the sturdiness and reliability of words on paper. My mother’s letters are truer and more complete than my self-absorbed and biased memories; she’s more alive to me in the written phrase “he NEEDS distractions!” than in hours of videotape or stacks of pictures of her.

The will to record indelibly, to set down stories in permanent words, seems to me akin to the conviction that we are larger than our biologies. I wonder if our current cultural susceptibility to the charms of materialism—our increasing willingness to see psychology as chemical, identity as genetic, and behavior as the product of bygone exigencies of human evolution—isn’t intimately related to the postmodern resurgence of the oral and the eclipse of the written: our incessant telephoning, our ephemeral e-mailing, our steadfast devotion to the flickering tube.

Have I mentioned that my father, too, wrote letters? Usually typewritten, usually prefaced with an apology for misspellings, they came much less frequently than my mother’s. One of the last is from December 1987:

This time of the year is always difficult for me. I’m ill at ease with all the gift-giving, as I would love to get things for people but lack the imagination to get the right things. I dread the shopping for things that are the wrong size or the wrong color or something not needed, and anticipate the problems of returning or exchanging. I like to buy tools, but Bob pointed out a problem with this category, when for some occasion I gave him a nice little hammer with good balance, and his comment was that this was the second or third hammer and I don’t need any more, thank you. And then there is the problem of gifts for your mother. She is so sentimental that it hurts me not to get her something nice, but she has access to my checking account with no restrictions. I have told her to buy something for herself, and say it is from me, so she can compete with the after-Christmas comment: “See what I got from my husband!” But she won’t participate in that fraud. So I suffer through the season.

In 1989, as his powers of concentration waned with his growing “nervousness & depression,” my father stopped writing letters altogether. My mother and I were therefore amazed to find, in the same drawer in which he’d left those addresses and birth dates, an unsent letter dated January 22, 1993—unimaginably late, a matter of weeks before his final breakdown. The letter was in an envelope addressed to my nephew Nick, who, at age six, had just begun to write letters himself. Possibly my father was ashamed to send a letter that he knew wasn’t fully coherent; more likely, given the state of his hippocampal health, he simply forgot. The letter, which for me has become an emblem of invisibly heroic exertions of the will, is written in a tiny penciled script that keeps veering away from the horizontal:

Dear Nick,

We got your letter a couple days ago and were pleased to see how well you were doing in school, particularly in math. It is important to write well, as the ability to exchange ideas will govern the use that one country can make of another country’s ideas.

Most of your nearest relatives are good writers, and thereby took the load off me. I should have learned better how to write, but it is so easy to say, Let Mom do it.

I know that my writing will not be easy to read, but I have a problem with the nerves in my legs and tremors in my hands. In looking at what I have written, I expect you will have difficulty to understand, but with a little luck, I may keep up with you.

We have had a change in the weather from cold and wet to dry with fair blue skies. I hope it stays this way. Keep up the good work.

Love, Grandpa

P.S. Thank you for the gifts.

MY FATHER’S HEART and lungs were very strong, and my mother was bracing herself for two or three more years of endgame when, one day in April 1995, he stopped eating. Maybe he was having trouble swallowing, or maybe, with his remaining shreds of will, he’d resolved to put an end to his unwanted second childhood.

His blood pressure was seventy over palpable when I flew into town. Again, my mother took me straight to the nursing home from the airport. I found him curled up on his side under a thin sheet, breathing shallowly, his eyes shut loosely. His muscle had wasted away, but his face was smooth and calm and almost entirely free of wrinkles, and his hands, which had changed not at all, seemed curiously large in comparison to the rest of him. There’s no way to know if he recognized my voice, but within minutes of my arrival his blood pressure climbed to 120/90. I worried then, worry even now, that I made things harder for him by arriving: that he’d reached the point of being ready to die but was ashamed to perform such a private or disappointing act in front of one of his sons.

My mother and I settled into a rhythm of watching and waiting, one of us sleeping while the other sat in vigil. Hour after hour, my father lay unmoving and worked his way toward death; but when he yawned, the yawn was his. And his body, wasted though it was, was likewise still radiantly his. Even as the surviving parts of his self grew ever smaller and more fragmented, I persisted in seeing a whole. I still loved, specifically and individually, the man who was yawning in that bed. And how could I not fashion stories out of that love—stories of a man whose will remained intact enough to avert his face when I tried to clear his mouth out with a moist foam swab? I’ll go to my own grave insisting that my father was determined to die and to die, as best he could, on his own terms.

We, for our part, were determined that he not be alone when he died. Maybe this was exactly wrong, maybe all he was waiting for was to be left alone. Nevertheless, on my sixth night in town, I stayed up and read a light novel cover to cover while he lay and breathed and loosed his great yawns. A nurse came by, listened to his lungs, and told me he must never have been a smoker. She suggested that I go home to sleep, and she offered to send in a particular nurse from the floor below to visit him. Evidently, the nursing home had a resident angel of death with a special gift for persuading the nearly dead, after their relatives had left for the night, that it was OK for them to die. I declined the nurse’s offer and performed this service myself. I leaned over my father, who smelled faintly of acetic acid but was otherwise clean and warm. Identifying myself, I told him that whatever he needed to do now was fine by me, he should let go and do what he needed to do.

Late that afternoon, a big early-summer St. Louis wind kicked up. I was scrambling eggs when my mother called from the nursing home and told me to hurry over. I don’t know why I thought I had plenty of time, but I ate the eggs with some toast before I left, and in the nursing-home parking lot I sat in the car and turned up the radio, which was playing the Blues Traveler song that was all the rage that season. No song has ever made me happier. The great white oaks all around the nursing home were swaying and turning pale in the big wind. I felt as though I might fly away with happiness.

And still he didn’t die. The storm hit the nursing home in the middle of the evening, knocking out all but the emergency lighting, and my mother and I sat in the dark. I don’t like to remember how impatient I was for my father’s breathing to stop, how ready to be free of him I was. I don’t like to imagine what he was feeling as he lay there, what dim or vivid sensory or emotional forms his struggle took inside his head. But I also don’t like to believe that there was nothing.

Toward ten o’clock, my mother and I were conferring with a nurse in the doorway of his room, not long after the lights came back on, when I noticed that he was drawing his hands up toward his throat. I said, “I think something is happening.” It was agonal breathing: his chin rising to draw air into his lungs after his heart had stopped beating. He seemed to be nodding very slowly and deeply in the affirmative. And then nothing.

After we’d kissed him goodbye and signed the forms that authorized the brain autopsy, after we’d driven through flooding streets, my mother sat down in our kitchen and uncharacteristically accepted my offer of undiluted Jack Daniel’s. “I see now,” she said, “that when you’re dead you’re really dead.” This was true enough. But, in the slow-motion way of Alzheimer’s, my father wasn’t much deader now than he’d been two hours or two weeks or two months ago. We’d simply lost the last of the parts out of which we could fashion a living whole. There would be no new memories of him. The only stories we could tell now were the ones we already had.

[2001]

IMPERIAL BEDROOM

PRIVACY, privacy, the new American obsession: espoused as the most fundamental of rights, marketed as the most desirable of commodities, and pronounced dead twice a week.

Even before Linda Tripp pressed the “Record” button on her answering machine, commentators were warning us that “privacy is under siege,” that “privacy is in a dreadful state,” that “privacy as we now know it may not exist in the year 2000.” They say that both Big Brother and his little brother, John Q. Public, are shadowing me through networks of computers. They tell me that security cameras no bigger than spiders are watching from every shaded corner, that dour feminists are monitoring bedroom behavior and watercooler conversations, that genetic sleuths can decoct my entire being from a droplet of saliva, that voyeurs can retrofit ordinary camcorders with a filter that lets them see through people’s clothing. Then comes the flood of dirty suds from the Office of the Independent Counsel, oozing forth through official and commercial channels to saturate the national consciousness. The Monica Lewinsky scandal marks, in the words of the philosopher Thomas Nagel, “the culmination of a disastrous erosion” of privacy; it represents, in the words of the author Wendy Kaminer, “the utter disregard for privacy and individual autonomy that exists in totalitarian regimes.” In the person of Kenneth Starr, the “public sphere” has finally overwhelmed—shredded, gored, trampled, invaded, run roughshod over—“the private.”

The panic about privacy has all the finger-pointing and paranoia of a good old American scare, but it’s missing one vital ingredient: a genuinely alarmed public. Americans care about privacy mainly in the abstract. Sometimes a well-informed community unites to defend itself, as when Net users bombarded the White House with e-mails against the “clipper chip,” and sometimes an especially outrageous piece of news provokes a national outcry, as when the Lotus Development Corporation tried to market a CD-ROM containing financial profiles of nearly half the people in the country. By and large, though, even in the face of wholesale infringements like the war on drugs, Americans remain curiously passive. I’m no exception. I read the editorials and try to get excited, but I can’t. More often than not, I find myself feeling the opposite of what the privacy mavens want me to. It’s happened twice in the last month alone.

On the Saturday morning when the Times came carrying the complete text of the Starr report, what I felt as I sat alone in my apartment and tried to eat my breakfast was that my own privacy—not Clinton’s, not Lewinsky’s—was being violated. I love the distant pageant of public life. I love both the pageantry and the distance. Now a President was facing impeachment, and as a good citizen I had a duty to stay informed about the evidence, but the evidence here consisted of two people’s groping, sucking, and mutual self-deception. What I felt, when this evidence landed beside my toast and coffee, wasn’t a pretend revulsion to camouflage a secret interest in the dirt; I wasn’t offended by the sex qua sex; I wasn’t worrying about a potential future erosion of my own rights; I didn’t feel the President’s pain in the empathic way he’d once claimed to feel mine; I wasn’t repelled by the revelation that public officials do bad things; and, although I’m a registered Democrat, my disgust was of a different order from my partisan disgust at the news that the Giants have blown a fourth-quarter lead. What I felt I felt personally. I was being intruded on.

A couple of days later, I got a call from one of my credit-card providers, asking me to confirm two recent charges at a gas station and one at a hardware store. Queries like this are common nowadays, but this one was my first, and for a moment I felt eerily exposed. At the same time, I was perversely flattered that someone, somewhere, had taken an interest in me and had bothered to phone. Not that the young male operator seemed to care about me personally. He sounded like he was reading his lines from a laminated booklet. The strain of working hard at a job he almost certainly didn’t enjoy seemed to thicken his tongue. He tried to rush his words out, to speed through them as if in embarrassment or vexation at how nearly worthless they were, but they kept bunching up in his teeth, and he had to stop and extract them with his lips, one by one. It was the computer, he said, the computer that routinely, ah, scans the, you know, the pattern of charges … and was there something else he could help me with tonight? I decided that if this young person wanted to scroll through my charges and ponder the significance of my two fill-ups and my gallon of latex paint, I was fine with it.

So here’s the problem. On the Saturday morning the Starr Report came out, my privacy was, in the classic liberal view, absolute. I was alone in my home and unobserved, unbothered by neighbors, unmentioned in the news, and perfectly free, if I chose, to ignore the report and do the pleasantly al dente Saturday crossword; yet the report’s mere existence so offended my sense of privacy that I could hardly bring myself to touch the thing. Two days later, I was disturbed in my home by a ringing phone, asked to cough up my mother’s maiden name, and made aware that the digitized minutiae of my daily life were being scrutinized by strangers; and within five minutes I’d put the entire episode out of my mind. I felt encroached on when I was ostensibly safe, and I felt safe when I was ostensibly encroached on. And I didn’t know why.

THE RIGHT to privacy—defined by Louis Brandeis and Samuel Warren, in 1890, as “the right to be let alone”—seems at first glance to be an elemental principle in American life. It’s the rallying cry of activists fighting for reproductive rights, against stalkers, for the right to die, against a national health-care database, for stronger data-encryption standards, against paparazzi, for the sanctity of employee e-mail, and against employee drug testing. On closer examination, though, privacy proves to be the Cheshire cat of values: not much substance, but a very winning smile.

Legally, the concept is a mess. Privacy violation is the emotional core of many crimes, from stalking and rape to Peeping Tommery and trespass, but no criminal statute forbids it in the abstract. Civil law varies from state to state but generally follows a forty-year-old analysis by the legal scholar Dean William Prosser, who dissected the invasion of privacy into four torts: intrusion on my solitude, the publishing of private facts about me which are not of legitimate public concern, publicity that puts my character in a false light, and appropriation of my name or likeness without my consent. This is a crumbly set of torts. Intrusion looks a lot like criminal trespass, false light like defamation, and appropriation like theft; and the harm that remains when these extraneous offenses are subtracted is so admirably captured by the phrase “infliction of emotional distress” as to render the tort of privacy invasion all but superfluous. What really undergirds privacy is the classical liberal conception of personal autonomy or liberty. In the last few decades, many judges and scholars have chosen to speak of a “zone of privacy,” rather than a “sphere of liberty,” but this is a shift in emphasis, not in substance: not the making of a new doctrine but the repackaging and remarketing of an old one.

Whatever you’re trying to sell, whether it’s luxury real estate or Esperanto lessons, it helps to have the smiling word “private” on your side. Last winter, as the owner of a Bank One Platinum Visa Card, I was offered enrollment in a program called PrivacyGuard®, which, according to the literature promoting it, “puts you in the know about the very personal records available to your employer, insurers, credit card companies, and government agencies.” The first three months of PrivacyGuard® were free, so I signed up. What came in the mail then was paperwork: envelopes and request forms for a Credit Record Search and other searches, also a disappointingly undeluxe logbook in which to jot down the search results. I realized immediately that I didn’t care enough about, say, my driving records to wait a month to get them; it was only when I called PrivacyGuard® to cancel my membership, and was all but begged not to, that I realized that the whole point of this “service” was to harness my time and energy to the task of reducing Bank One Visa’s fraud losses.

Even issues that legitimately touch on privacy are rarely concerned with the actual emotional harm of unwanted exposure or intrusion. A proposed national Genetic Privacy Act, for example, is premised on the idea that my DNA reveals more about my identity and future health than other medical data do. In fact, DNA is as yet no more intimately revealing than a heart murmur, a family history of diabetes, or an inordinate fondness for Buffalo chicken wings. As with any medical records, the potential for abuse of genetic information by employers and insurers is chilling, but this is only tangentially a privacy issue; the primary harm consists of things like job discrimination and higher insurance premiums.