Полная версия

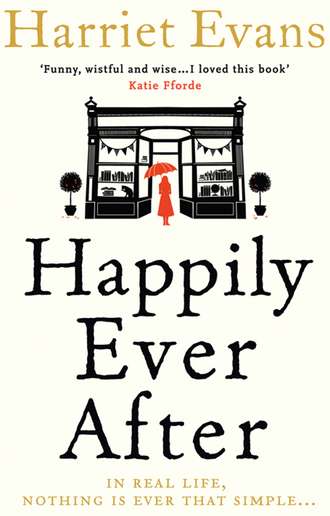

Happily Ever After

In February, Elle’s best friend from school, Karen, had said she could come and sleep on her sofa. ‘You’re never going to find a job in publishing in a tiny village in Sussex, Elle,’ she’d said briskly. ‘Bite the bullet and come to London.’ And Elle had accepted, nervous but also overwhelmed with excitement. London. She’d dreamed of moving to London, of living in the big city, since she was a little girl. She’d conquer it. She’d own grey wellington boots with heels. And have a matching grey briefcase, like the Athena poster of the city girl hanging off the back of a Routemaster bus blowing a kiss to her handsome boyfriend that Elle still had in her bedroom.

But London was very far from the welcoming and bustling literary salon Elle had expected it to be. Notting Hill was grimy, full of cracked pavements and crack addicts, and sleeping on the floor in Karen’s was no fun. She’d been here two months now. She’d applied for every job going, written to every publisher she could find in the Writers’ and Artists’ Yearbook to ask them for work experience. But no one was interested. She was discovering she’d been totally naive to think they would be. She’d had four interviews, and this one today, at a major publishing house, was like the big one that had to work out, and she’d clearly totally one hundred per cent blown it. She’d thought she was so prepared: she had read everything, everything, in fact Karen said the trouble with her was she couldn’t get her nose out of a book.

She hated the way she spent her days now. She’d sit in the silent flat, feeling crappy about herself and knowing she should buck up, watching Richard and Judy and dreading the moment when Karen would get back from work and say, in an increasingly unsympathetic tone, ‘So, what did you get up to today then?’ Her social life consisted of going to the pub or sitting around in the dark flat off Ladbroke Grove waiting for the electricity meter to run out. Plus Karen’s other flatmates, Cara the chef and Alex the ad man, clearly found Elle a hindrance rather than a delightful addition to communal living.

On the Tube back to Notting Hill, Elle wondered for the first time if she should have come to London at all. It wasn’t how she’d expected it, and even though she was used to not fitting in, she’d never felt less welcome anywhere, in her whole life. It struck her that if she packed up her meagre possessions this evening and got a train first thing tomorrow, she’d be back at her mother’s by lunchtime. But then – what? She and her mother, in the converted barn Mandana had bought after the divorce, doing what? Would it be worse than being here? Probably not.

Elle had a stroke of luck as she got off at Notting Hill Gate. Someone had left an Evening Standard behind on a seat and she scooped it up. It was a cold April day and she shivered in her thin coat, the paper clamped under one arm, as she walked through the empty streets, trying not to let her mood sink any lower.

It was just really hard, though, trying to find your place in the world. At university it had been so easy. You knew where you were going each day, what you were doing, and with whom. After university, the rules had suddenly changed, and Elle felt she’d been left behind. But the irony was, she knew exactly what she wanted! She’d always known! She just wanted to work with books, to read fine literature, to meet authors and to learn to edit, to have conversations like those she used to have with her Victorian Literature tutor Dr Wilson, about the Brontës and Austen and whether Middlemarch was the great Victorian novel or not and … that sort of thing. Of course, she knew she’d have to start at the bottom – she didn’t mind that at all, in fact she rather thought she’d like it. But that didn’t seem to make a difference.

What am I going to do? she thought to herself, walking briskly, head down. Will I just be someone who falls through the cracks in society and never gets a job? And turns into one of those weirdos who keeps every newspaper from 1976 and carries a brown satchel and goes through the bins? Oh, my God, is that going to be me?

The cold sharp breeze stung Elle’s eyes. She wiped them with the back of her hand, and the Evening Standard dislodged and fell on the pavement, where a rolling gust of wind carried it off, into the middle of the road. She ran after it, and as she picked it up, noticed it was a week out of date. One whole week. She heaved her shoulders, and looked round for somewhere to dump the offending newspaper. There wasn’t even a bin and she wasn’t so far sunk into depression that she would just chuck it on the pavement. She stomped back towards the flat, muttering under her breath, not caring if she was taking one further step down the line towards being a newspaper-hoarding, bin-rifling weirdo, and thinking that the world was a cruel, cruel place.

ELLE SAT AT the kitchen table, reading the week-old newspaper and sipping a cup of tea, glad to be out of the cold, but still shaking at the injustice of the day she’d had. Absolutely no jobs yet again in the Evening Standard. She’d missed it last week; it had been sold out, and even if she’d had it a week ago it’d have been useless, unless she wanted to go into local government or work for a magazine called Red Knave, and she was sure she didn’t.

Washing-up was piled high in the sink. They’d had people round the night before; Alex had made pasta and a bong, and Karen had made everyone sing ‘Total Eclipse of the Heart’ into wooden spoons. Elle had wanted to go to bed early to prepare for her interview, but she couldn’t really get out her duvet and lie on the sofa while five other people were glugging Bulgarian white wine out of a screwtop bottle and yelling about the upcoming election.

Elle knew she should do the washing-up in a minute; perhaps then Alex would stop glaring at her when he came in and saying, ‘Oh. Hi.’ Which meant, ‘Oh. You’re still here, blighting my life.’ She didn’t like Alex much, all he seemed to do was show off his new mobile phone and take calls on it, then play Tomb Raider all weekend in the sitting room with his friend Fred. Elle had snogged Fred only the week before, more because she’d been trying to get to sleep and it seemed easier to snog him and then let them get on with playing Tomb Raider than tell them to leave. Plus Fred was actually an OK snog, even if she didn’t have much to say to him. He’d been there yesterday too – but he’d been in a funny mood, and she wasn’t sure he was interested any more, which wouldn’t be a surprise, to be honest. He had a job and a flatshare, he wasn’t sleeping in someone’s sitting room and reading week-old newspapers.

Elle took another sip of tea, and turned from the out-of-date Jobs section to the news pages, cravenly aware this was a waste of time. There was a picture of Tony Blair, meeting some old ladies, and smiling. He looked young and tanned, and his hair was pretty good. Elle couldn’t help thinking that was a plus point, not that it should matter but somehow it added to the overall romantic-lead sheen of him. Tony Blair always made her think of that line in Pride and Prejudice when Jane asks Lizzy how long she has loved Mr Darcy for, and Lizzy replies, ‘It has been coming on so gradually, that I hardly know when it began. But I believe I must date it from my first seeing his beautiful grounds at Pemberley.’

Thinking of this now made her smile weakly. She closed her eyes and thought about Lizzy Bennet and Mr Darcy, wondering how they’d talk to each other after they were married and living at Pemberley. Because that always bothered her, what happened after the couple got over their misunderstandings to live happily ever after. She couldn’t help thinking Mr Darcy wouldn’t be sympathetic if Elizabeth ordered the wrong dinner service when a duke came to stay. She had seen what had happened with her parents, how vicious it had been, and Elle couldn’t ever imagine that they’d once been in love.

John and Mandana had been divorced for seven years. Sometimes it seemed ages ago, sometimes she could still remember, as if it were yesterday, their old, cosy, normal life at Willow Cottage. The final papers had come through as Elle was preparing for her GCSEs. There was a lot of lip service paid to not letting it affect her exams, and people treated her very carefully, as if someone had died: the headmistress even called her into her office for ‘a little chat’, to see if she was all right. Elle hadn’t known how to answer when Mrs Barber had asked her how she was coping. How did you explain that you were a horrible person, because you were glad they were splitting up, glad they wouldn’t be together any more, glad her dad was going away because these days he just seemed to upset her mum so much? Even when they had to sell the house and move to a barn outside Shawcross, and even when John remarried with what Elle overheard a friend say to Mandana was ‘insensitive haste’ she knew she didn’t care in the way she should. She’d wondered whether she was a homicidal maniac – she’d read a book about them and one of the first signs was a lack of empathy. But Elle was just glad it was over, because it was horrible living like that.

To her secret relief, however, Rhodes obviously felt the same way. He’d gone to college in the States and was now an analyst, working for Bloomberg in New York. The last time she’d seen him was at Christmas at Mum’s, and it had been awful – Mum had been drunk, Rhodes had told her she drank too much and was pathetic and anyone could see why Dad had left her, and then stormed out. Elle hadn’t spoken to him since. Mum always drank too much, but it had got worse, that summer in Skye, as their marriage got worse. Elle never knew what came first, like the chicken and the egg. She only knew their old life, where her parents had seemed OK, was over.

So Elle didn’t wonder what might have happened if her parents had stayed together. She knew the real ending after the ending. She wondered about people like Lizzy and Darcy, or Beatrice and Benedick instead. Often she felt she was the only person who didn’t believe they’d stay together, after the book or the play ended. She couldn’t help it; she just didn’t believe it.

She was pondering this, her knees under her chin, legs wedged against the table, when the door slammed and Alex came in.

‘Oh, hi, Elle,’ he said, not looking at her, and slamming his man-bag down on the table. ‘How’s it going? Any luck today then?’

‘OK, thanks,’ Elle said. ‘Yeah, I—’

‘I’m not staying,’ Alex said. ‘Meeting some guys from work at the pub. Just stopped off to change my shirt.’

‘Oh, right,’ said Elle, who found Alex’s obsession with sharp Ben Sherman shirts half tragic, half touching.

‘Hey.’ He stopped and grabbed the paper from her. ‘Can I just check something? Were you looking at it?’

‘At the jobs, but it’s fine, there’s nothing in it,’ Elle said, desperate to talk, even if Alex obviously wasn’t interested. ‘It’s a week old, anyway –’

Alex ignored her and started turning the pages. ‘Our new print campaign for Cape Town should be in here somewhere, we rolled it out last week and the fucking muppets haven’t sent us any copies yet.’

‘But this is last week’s –’

He ignored her, and struggled to turn the pages. ‘That’s fine. Where is it? Hey! There! How cool is that? Yeah, looks good.’

Elle followed his jabbing finger. ‘“Visit Cape Town, for a World of Possibilities”,’ she read. ‘That’s great.’

She nodded politely as Alex talked, and looked down again, her eye caught by something, she didn’t know why. And there, right in the middle of the Travel section, amongst ads for holiday lets in Cornwall and cheap flights to Thailand, she suddenly saw the following:

Editorial Secretary Required for Established Independent Publishing House

Enthusiastic Self-Starter / Graduate. Must have office experience

Competitive Salary: £11,000

Please send curricula vitae by post to:

Miss Elspeth MacReady

c/o Bluebird Books Ltd, Bedford Square

‘What’s that doing there?’ Elle asked. She snatched the paper out of Alex’s hand. ‘It’s – what’s it doing there?’

‘Don’t know.’ Alex stared at her, annoyed. ‘Actually, Elle, I was looking at that.’

‘Sorry, Alex,’ Elle said, clutching the paper to her bosom and looking at him imploringly, almost in a panic: what if he took the paper away, flung it out of the window, how would she get it back? ‘It’s a job, it sounds perfect… . I don’t know why it’s there, it’s in the wrong place… . Please, let me …’ She stared again at the text. ‘“Send curricula vitae … care of Bluebird Books”.’ She bit her lip. ‘Bluebird Books – I’ve heard of them! They’re proper, they – they’re old!’ She ran into Karen’s bedroom and scanned the precariously built IKEA Billy bookcase, crammed full of well-worn blockbusters, their cracked spines stamped with gold. ‘Yes, I knew it! They publish Victoria Bishop! And … Old Tom! They publish Old Tom. Well, Granny Bee would have been pleased.’ She glanced at her watch. It was nearly five thirty p.m. Too late to catch the post. There was no telephone number, either. No, a voice inside her head said. You’re going to go for this. You’re going to do something about this, instead of sitting there feeling sorry for yourself.

Elle bit her lip and marched back to the hall, pulled out a telephone directory, and thumbed through it, kneeling on the ground. Alex came into the hall and watched her.

‘Can I have the paper back now, please?’ he said, reaching forward.

‘No! Just give me ONE SECOND, Alex, PLEASE!’ Elle heard herself bellowing. Alex stepped back, annoyed.

‘You’re really starting to outstay your fucking welcome, you know,’ he murmured.

Elle jabbed her finger on the page, and started dialling. It was a week old, that ad – even if it was in the wrong place, what were the chances? ‘I’m sorry, Alex,’ she said. ‘It’s probably hopeless, but I’ve got to give it a go— Hello?’

‘Good evening,’ said a low voice, a girl’s. ‘Bluebird Books, how may I help you?’

‘Hello – yes. I – er – I just saw an advert in last week’s Evening Standard for the job of editorial secretary – I wanted to ask if I could still apply? There wasn’t a closing date.’

There was a silence, and then the voice spoke again, this time even lower, much closer to the speaker. ‘The job ad? You saw it? You want to apply? Oh, thank fuck.’ She coughed. ‘I’m so sorry. I mean, thank goodness.’

‘Thank goodness?’ Elle was astonished. This wasn’t the reception she was used to. The last job she’d rung up about, an editorial assistant’s job at an independent publisher in Bristol, the man on the line had said, ‘Sorry, position’s been filled,’ and put the phone down, like a scene from a film about the Great Depression.

‘You don’t understand.’ The girl on the other end sighed, and Elle realised she was around her age, despite the huskiness of her Lancashire-tinged voice. ‘No one’s applied,’ she said quietly. ‘Not a soul. I don’t understand it. And Miss Sassoon keeps checking, and we have to have someone in soon, otherwise she’ll go totally mad – it’s been a week, a week, and nothing! Nothing!’

‘Look,’ Elle said. ‘I think I know why.’

‘Why? Why what?’ The voice rose sharply again.

‘Well. The ad’s in the holiday homes section,’ she said quickly. ‘It’s a total fluke I saw it.’

‘The what?’

‘Holiday homes. Between an ad for a nice cottage in Norfolk and a bungalow in the Lizard.’

There was a terrible silence, pregnant with meaning.

‘Oh … FUCK,’ the voice whispered. ‘FUCK. She is going to kill me. K.I.L.L.L.L. me. How did I—’

‘I don’t think it’s your fault, is it?’ Elle said. ‘It’s the people who do the ads, they put it in wrongly.’

‘She won’t see it like that. Oh, God, oh, Jesus,’ the voice said. ‘What am I going to do? That’s why. Oh, Jesus. She’s going to ask me tomorrow. Oh, Christ.’

‘Listen here –’ Elle said, authoritatively. She nodded to herself. Go for it! ‘Why don’t you get me in for an interview. Eh?’

There was another silence. ‘Yes,’ the girl said eventually, breathing out with a long whistle. ‘OK, can you come in tomorrow, first thing? She’s not got anything on then, neither’s he. And if you’re rubbish, I’ll just confess and we can do it again so we’ve got someone by the time Posy comes back from holiday. ’Cause she said she’d leave if she came back and they hadn’t replaced Hannah … Man alive.’ There was a loud thudding sound.

‘What was that?’ Elle asked, alarmed.

‘I was banging my head on the desk. Look, if you come in, please don’t tell Miss Sassoon. Please.’

‘Of course I won’t,’ said Elle. ‘Who is she, anyway?’

‘You’ve never heard of Felicity Sassoon?’

‘No, never.’

‘And you want to work in publishing?’

‘Yes,’ Elle said. ‘Oh, I really do.’

‘Well, you’ve got to get this job. So I’m going to help you. Hold on.’ There was some rustling on the line. ‘Just checking everyone’s gone, it’s Rory’s birthday, they’ve gone to the pub. Well, Miss Sassoon’s father set up Bluebird, ages ago. It’s er, something like the last of the old publishers in Bedford Square and she’s really into that, so go on about that, I did and it worked a treat. You’ll be working for her son, Rory. And Posy, who’s another editor. Rory does crime and young trendy fiction, Posy does women’s fiction, sagas, some of Felicity’s authors.’ She stopped. ‘I mean, I presume you actually want to work with books like that, don’t you? You want to get into publishing? They’ll ask you what you’ve read lately, all that stuff, if you know any Bluebird authors. Have you got something to say?’

Elle took a deep breath. ‘Well, I loved Captain Corelli and I’m halfway through Bridget Jones, plus I’m a huge fan of Victoria Bishop and my granny had all of Old Tom’s Devon stories, but I also studied English at university and my favourite author is probably Charlotte Brontë.’

‘Oh, they’ll beat that out of you soon enough, but it’s a start. OK, so next—’

‘Hold on,’ said Elle. ‘What’s your name?’

‘It’s Libby,’ said the voice. ‘Libby Yates. What’s yours?’

‘Eleanor Bee,’ said Elle. ‘But call me Elle, everyone does.’

‘Do they now.’ The laconic tone was back, and you’d never have known she’d been so flustered. ‘Hello, Eleanor Bee. On with the tutorial. So …’

JUST UNDER TWO weeks later, on Tuesday 6 May, Eleanor Bee stood at the bottom of the steps of a big house and stared at the blue enamel sign hanging above her.

‘I have confidence,’ she muttered to herself. She looked down at her smart charcoal grey trousers – new from Warehouse, on Saturday – and the raspberry pink short-sleeved jumper, at her beautiful soft black Mary Janes with the small heel from Pied a Terre which were only twenty pounds in the Christmas sale and which she was still unable to quite believe were hers. It was a beautiful spring day, and the newly green trees in Bedford Square swayed behind her. In the distance she could hear the clanging of a Routemaster bus bell, but otherwise it was completely quiet. Eleanor climbed the stairs and rang on the front door.

She was so nervous, she felt her knees might give way underneath her. She’d been here before, for her interview the week before last, but it seemed ages ago. Perhaps the whole thing was a huge mistake. Elle couldn’t shake the feeling that she was an imposter – she was only standing here because no one else had applied, and because the terrifying Miss Sassoon, who’d briefly interviewed her, had been impressed that she’d heard of Forever Amber, because the only other person she’d seen had been some daughter of a friend of a friend, and she’d never heard of it. Well, Elle had thought, why were you interviewing the daughter of a friend of a friend? That’s no way to find the best people, surely?

‘So you’ve read it?’ Miss Sassoon had asked.

‘Oh, yes.’ Elle was very fond of Forever Amber. She’d been reading it during the awful holiday in Skye all those years ago. ‘I couldn’t put it down. I – I enjoyed it even more than Gone with the Wind.’

‘That,’ Miss Sassoon had said firmly, ‘is a subject for another day.’ Elle thought she’d annoyed her, but Miss Sassoon had smiled and called for Libby to show her out, and then she’d been interviewed by Rory, who was very nice, in his early thirties, friendly and far less scary than his mother, so she’d relaxed and just chatted, and he’d teased her about liking the Spice Girls and then she’d left, and Libby had rung her at home that evening to say thanks. ‘I think they liked you. I know Rory’s bored of temps and the old lady just wants it sorted out, ASAP. You’re definitely in with a chance.’

And for once that chance was hers. They’d given her the job, and she was here and now – she had no idea what came next. Elle rang the doorbell again, more firmly.

‘Helloooo?’ an elderly voice said into the intercom.

‘Hello? It’s Eleanor … Eleanor Bee. It’s my first day, I’m Rory and Posy’s new secretary, they told me to get here for ten …?’

‘First floor. Please commmee innnn… .’ the intercom said in querulous tones.

Elle climbed the wide stairs to the first floor and at the top she pushed open a swinging door to be greeted by Elspeth MacReady, office manager, wiping her hands on her skirt, and bending double, her rheumy eyes darting unhappily about her.

‘Good morning, Eleanor,’ she said formally. ‘Good to see you again. Welcome to Bluebird Books. Mr Rory is in a meeting. He asked me to get you settled in. Here we are.’

Elle looked around her, taking it all in once more. A real-life publishing house. Where people made books, all day. And she was here, she was one of them! What a magical place! Strung out across the oatmeal carpet on the huge first floor were a collection of yellowing wooden desks surrounded by wall dividers, greying filing cabinets, and books. There were books everywhere, on shelves, in piles on floors, spilling out of cardboard boxes. It was strangely at odds with the beautiful old wood panelling on the walls, the four or five old portraits in gilt frames. She could see Bedford Square in the sunshine from the huge windows.

‘Do you know where you will be sitting?’ Elspeth asked. ‘Has anyone explained to you the rules for the kitty, or about the keys?’

‘No,’ said Elle. ‘I only really – I met Rory briefly and then—’

‘Oh, dear. Oh, dear.’ Elspeth shook her head. ‘Someone should have told you –’ She sighed, and her long thin frame shuddered.

‘I’m sorry,’ Elle said.

‘It’s fine. Now. Where to start. Firstly, each employee is issued with a key. This key is extremely important. The last person to leave the building at night turns the lights off and locks the front door with the key.’

‘Yes …?’ Elle said weakly. ‘Then what?’

‘Well, that’s it,’ Elspeth said. ‘But it’s very important.’

‘Of course.’

‘And we ask that people, if they wish to join, contribute two pounds a month to the kitty for tea and coffee, and Miss Sassoon very kindly provides biscuits.’

‘Right,’ said Elle. ‘And …?’

‘Well, that’s also it,’ said Elspeth. ‘For the moment,’ she added, firmly. ‘Ah. Here is your desk. And this is Libby. Have you met already?’

‘Yes,’ said Elle, smiling gratefully at Libby, who was typing furiously, a Dictaphone machine next to her keyboard. Libby stopped and took her headphones off, raising a hand in greeting and pushing her dark blonde bob out of her eyes. She was wearing Anaïs Anaïs; Elle remembered it from their first meeting.

‘Hi, Elle. Nice to have you here.’

Elle looked away from her, blushing as if they had been caught red-handed, like secret lovers. She stared at the desk in front of her. ‘Oh, my goodness,’ she said.

‘Is there a problem?’ Elspeth asked, panic in her voice.

‘I have a phone,’ Elle said, unable to believe it. ‘And a computer.’