Полная версия

Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali

So we see that citta can be pulled in two directions: outwards towards its mother, nature, prakrti, or inwards towards its father, spirit, purusa. The role of yoga is to show us that the ultimate goal of citta is to take the second path, away from the world to the bliss of the soul. Yoga both offers the goal and supplies the means to reach it. He who finds his soul is Yogesvara, Lord or God of yoga, or Yogiraja, a King among yogis.

Now, nothing is left to be known or acquired by him.

Caution

Patañjali warns that even such exalted yogis are not beyond all danger of relapse. Even when oneness between cit and citta is achieved, inattention, carelessness, or pride in one’s achievement await opportunity to return, and fissure the consciousness. In this loss of concentration, old thoughts and habits may re-emerge to disturb the harmony of kaivalya.

If this takes place, the yogi has no alternative but to resume his purificatory struggle in the same way as less evolved people combat their own grosser afflictions.

The dawn of spiritual and sorrowless light

If the Yogesvara’s indivisible state is unwaveringly sustained, a stream of virtue pours from his heart like torrential rain: dharma megha samadhi, or rain-cloud of virtue or justice. The expression has two complementary overtones. Dharma means duty; megha means cloud. Clouds may either obscure the sun’s light or clear the sky by sending down rain to reveal it. If citta’s union with the seer is fissured it drags its master towards worldly pleasures (bhoga). If union is maintained it leads the aspirant towards kaivalya. Through yogic discipline, consciousness is made virtuous so that its possessor can become, and be, a yogi, a jñanin, a bhaktan and a paravairagin.

All actions and reactions cease in that person who is now a Yogesvara. He is free from the clutches of nature and karma. From now on, there is no room in his citta for the production of effects; he never speaks or acts in a way that binds him to nature. When the supply of oil to a lamp is stopped, the lamp is extinguished. In this yogi, when the fuel of desires dries out, the lamp of the mind cannot burn, and begins to fade on its own. Then infinite wisdom issues forth spontaneously.

The knowledge that is acquired through senses, mind and intellect is insignificant beside that emanating from the vision of the seer. This is the real intuitive knowledge.

When the clouds disappear, the sky clears and the sun shines brilliantly. When the sun shines, does one need artificial light to see? When the light of the soul blazes, the light of consciousness is needed no longer.

Nature and its qualities cease to affect the fulfilled yogi. From now on they serve him devotedly, without interfering with or influencing his true glory. He understands the sequence of time and its relationship with nature. He is crowned with the wisdom of living in the eternal Now. The eternal Now is Divine and he too is Divine. All his aims of life are fulfilled. He is a krtharthan, a fulfilled soul, one without equal, living in benevolent freedom and beatitude. He is alone and complete. This is kaivalya.

Patañjali begins the Yoga Sutras with atha, meaning ‘now’, and ends with iti, ‘that is all’. Besides this search for the soul, there is nothing.

Part one

Samadhi Pada

Samadhi means yoga and yoga means samadhi. This pada therefore explains the significance of yoga as well as of samadhi: both mean profound meditation and supreme devotion.

For aspirants endowed with perfect physical health, mental poise, discriminative intelligence and a spiritual bent, Patañjali provides guidance in the disciplines of practice and detachment to help them attain the spiritual zenith, the vision of the soul (atma-darsana).

The word citta has often been translated as ‘mind’. In the West, it is considered that mind not only has the power of conation or volition, cognition and motion, but also that of discrimination.

But citta really means ‘consciousness’. Indian philosophers analysed citta and divided it into three facets: mind (manas), intelligence (buddhi) and ego, or the sense of self (ahamkara). They divided the mental body into two parts: the mental sheath and the intellectual sheath. People have thus come to think of consciousness and mind as the same. In this work, consciousness refers both to the mental sheath (manomaya kosa) as mind, and to the intellectual sheath (vijñanamaya kosa) as wisdom. Mind acquires knowledge objectively, whereas intelligence learns through subjective experience, which becomes wisdom. As cosmic intelligence is the first principle of nature, so consciousness is the first principle of man.

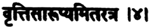

With prayers for divine blessings, now begins an exposition of the sacred art of yoga.

Now follows a detailed exposition of the discipline of yoga, given step by step in the right order, and with proper direction for self-alignment.

Patañjali is the first to offer us a codification of yoga, its practice and precepts, and the immediacy of the new light he is shedding on a known and ancient subject is emphasized by his use of the word ‘now’. His reappraisal, based on his own experience, explores fresh ground, and bequeathes us a lasting, monumental work. In the cultural context of his time his words must have been crystal clear, and even to the spiritually impoverished modern mind they are never confused, although they are often almost impenetrably condensed.

The word ‘now’ can also be seen in the context of a progression from Patañjali’s previous works, his treatises on grammar and on ayurveda. Logically we must consider these to predate the Yoga Sutras, as grammar is a prerequisite of lucid speech and clear comprehension, and ayurvedic medicine of bodily cleanliness and inner equilibrium. Together, these works served as preparation for Patañjali’s crowning exposition of yoga: the cultivation and eventual transcendence of consciousness, culminating in liberation from the cycles of rebirth.

These works are collectively known as moksa sastras (spiritual sciences), treatises which trace man’s evolution from physical and mental bondage towards ultimate freedom. The treatise on yoga flows naturally from the ayurvedic work, and guides the aspirant (sadhaka) to a trained and balanced state of consciousness.

In this first chapter Patañjali analyses the components of consciousness and its behavioural patterns, and explains how its fluctuations can be stilled in order to achieve inner absorption and integration. In the second, he reveals the whole linking mechanism of yoga, by means of which ethical conduct, bodily vigour and health and physiological vitality are built into the structure of the human evolutionary progress towards freedom. In the third chapter, Patañjali prepares the mind to reach the soul. In the fourth, he shows how the mind dissolves into the consciousness and consciousness into the soul, and how the sadhaka drinks the nectar of immortality.

The Brahma Sutra, a treatise dealing with Vedanta philosophy (the knowledge of Brahman), also begins with the word atha or ‘now’: athato Brahma jijñasa. There, ‘now’ stands for the desire to know Brahman. Brahman is dealt with as the object of study and is discussed and explored throughout as the object. In the Yoga Sutras, it is the seer or the true Self who is to be discovered and known. Yoga is therefore considered to be a subjective art, science and philosophy. ‘Yoga’ has various connotations as mentioned at the outset, but here it stands for samadhi, the indivisible state of existence.

So, this sutra may be taken to mean: ‘the disciplines of integration are here expounded through experience, and are given to humanity for the exploration and recognition of that hidden part of man which is beyond the awareness of the senses’.

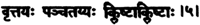

Yoga is the cessation of movements in the consciousness.

Yoga is defined as restraint of fluctuations in the consciousness. It is the art of studying the behaviour of consciousness, which has three functions: cognition, conation or volition, and motion. Yoga shows ways of understanding the functionings of the mind, and helps to quieten their movements, leading one towards the undisturbed state of silence which dwells in the very seat of consciousness. Yoga is thus the art and science of mental discipline through which the mind becomes cultured and matured.

This vital sutra contains the definition of yoga: the control or restraint of the movement of consciousness, leading to their complete cessation.

Citta is the vehicle which takes the mind (manas) towards the soul (atma). Yoga is the cessation of all vibration in the seat of consciousness. It is extremely difficult to convey the meaning of the word citta because it is the subtlest form of cosmic intelligence (mahat). Mahat is the great principle, the source of the material world of nature (prakrti), as opposed to the soul, which is an offshoot of nature. According to samkhya philosophy, creation is effected by the mingling of prakrti with Purusa, the cosmic Soul. This view of cosmology is also accepted by the yoga philosophy. The principles of Purusa and prakrti are the source of all action, volition and silence.

Words such as citta, buddhi and mahat are so often used interchangeably that the student can easily become confused. One way to structure one’s understanding is to remember that every phenomenon which has reached its full evolution or individuation has a subtle or cosmic counterpart. Thus, we translate buddhi as the individual discriminating intelligence, and consider mahat to be its cosmic counterpart. Similarly, the individuated consciousness, citta, is matched by its subtle form cit. For the purpose of Self-Realization, the highest awareness of consciousness and the most refined faculty of intelligence have to work so much in partnership that it is not always useful to split hairs by separating them. (See Introduction, part I – Cosmology of Nature.)

The thinking principle, or conscience (antahkarana) links the motivating principle of nature (mahat) to individual consciousness which can be thought of as a fluid enveloping ego (ahamkara), intelligence (buddhi) and mind (manas). This ‘fluid’ tends to become cloudy and opaque due to its contact with the external world via its three components. The sadhaka’s aim is to bring the consciousness to a state of purity and translucence. It is important to note that consciousness not only links evolved or manifest nature to non-evolved or subtle nature; it is also closest to the soul itself, which does not belong to nature, being merely immanent in it.

Buddhi possesses the decisive knowledge which is determined by perfect action and experience. Manas gathers and collects information through the five senses of perception, jñanendriyas, and the five organs of action, karmendriyas. Cosmic intelligence, ego, individual intelligence, mind, the five senses of perception and the five organs of action are the products of the five elements of nature – earth, water, fire, air and ether (prthvi, ap, tejas, vayu and akasa) – with their infra-atomic qualities of smell, taste, form or sight, touch and sound (gandha, rasa, rupa, sparsa and sabda).

In order to help man to understand himself, the sages analysed humans as being composed of five sheaths, or kosas:

Sheath Corresponding element Anatomical (annamaya) Earth Physiological (pranamaya) Water Mental (manomaya) Fire Intellectual (vijñanamaya) Air Blissful (anandamaya) EtherThe first three sheaths are within the field of the elements of nature. The intellectual sheath is said to be the layer of the individual soul (jivatman), and the blissful sheath the layer of the universal Soul (paramatman). In effect, all five sheaths have to be penetrated to reach emancipation. The innermost content of the sheaths, beyond even the blissful body, is purusa, the indivisible, non-manifest One, the ‘void which is full’. This is experienced in nirbija samadhi, whereas sabija samadhi is experienced at the level of the blissful body.

If ahamkara (ego) is considered to be one end of a thread, then antaratma (Universal Self) is the other end. Antahkarana (conscience) is the unifier of the two.

The practice of yoga integrates a person through the journey of intelligence and consciousness from the external to the internal. It unifies him from the intelligence of the skin to the intelligence of the self, so that his self merges with the cosmic Self. This is the merging of one half of one’s being (prakrti) with the other (purusa). Through yoga, the practitioner learns to observe and to think, and to intensify his effort until eternal joy is attained. This is possible only when all vibrations of the individual citta are arrested before they emerge.

Yoga, the restraint of fluctuating thought, leads to a sattvic state. But in order to restrain the fluctuations, force of will is necessary: hence a degree of rajas is involved. Restraint of the movements of thought brings about stillness, which leads to deep silence, with awareness. This is the sattvic nature of the citta.

Stillness is concentration (dharana) and silence is meditation (dhyana). Concentration needs a focus or a form, and this focus is ahamkara, one’s own small, individual self. When concentration flows into meditation, that self loses its identity and becomes one with the great Self. Like two sides of a coin, ahamkara and atma are the two opposite poles in man.

The sadhaka is influenced by the self on the one hand and by objects perceived on the other. When he is engrossed in the object, his mind fluctuates. This is vrtti. His aim should be to distinguish the self from the objects seen, so that it does not become enmeshed by them. Through yoga, he should try to free his consciousness from the temptations of such objects, and bring it closer to the seer. Restraining the fluctuations of the mind is a process which leads to an end: samadhi. Initially, yoga acts as the means of restraint. When the sadhaka has attained a total state of restraint, yogic discipline is accomplished and the end is reached: the consciousness remains pure. Thus, yoga is both the means and the end.

(See I.18; II.28.)

Then, the seer dwells in his own true splendour.

When the waves of consciousness are stilled and silenced, they can no longer distort the true expression of the soul. Revealed in his own nature, the radiant seer abides in his own grandeur.

Volition being the mode of behaviour of the mind, it is liable to change our perception of the state and condition of the seer from moment to moment. When it is restrained and regulated, a reflective state of being is experienced. In this state, knowledge dawns so clearly that the true grandeur of the seer is seen and felt. This vision of the soul radiates without any activity on the part of citta. Once it is realized, the soul abides in its own seat.

(See I.16, 29, 47, 51; II.21, 23, 25; III.49, 56; IV.22, 25, 34.)

At other times, the seer identifies with the fluctuating consciousness.

When the seer identifies with consciousness or with the objects seen, he unites with them and forgets his grandeur.

The natural tendency of consciousness is to become involved with the object seen, draw the seer towards it, and move the seer to identify with it. Then the seer becomes engrossed in the object. This becomes the seed for diversification of the intelligence, and makes the seer forget his own radiant awareness.

When the soul does not radiate its own glory, it is a sign that the thinking faculty has manifested itself in place of the soul.

The imprint of objects is transmitted to citta through the senses of perception. Citta absorbs these sensory impressions and becomes coloured and modified by them. Objects act as provender for the grazing citta, which is attracted to them by its appetite. Citta projects itself, taking on the form of the objects in order to possess them. Thus it becomes enveloped by thoughts of the object, with the result that the soul is obscured. In this way, citta becomes murky and causes changes in behaviour and mood as it identifies itself with things seen. (See III.36.)

Although in reality citta is a formless entity, it can be helpful to visualize it in order to grasp its functions and limitations. Let us imagine it to be like an optical lens, containing no light of its own, but placed directly above a source of pure light, the soul. One face of the lens, facing inwards towards the light, remains clean. We are normally aware of this internal facet of citta only when it speaks to us with the voice of conscience.

In daily life, however, we are very much aware of the upper surface of the lens, facing outwards to the world and linked to it by the senses and mind. This surface serves both as a sense, and as a content of consciousness, along with ego and intelligence. Worked upon by the desires and fears of turbulent worldly life, it becomes cloudy, opaque, even dirty and scarred, and prevents the soul’s light from shining through it. Lacking inner illumination, it seeks all the more avidly the artificial lights of conditioned existence. The whole technique of yoga, its practice and restraint, is aimed at dissociating consciousness from its identification with the phenomenal world, at restraining the senses by which it is ensnared, and at cleansing and purifying the lens of citta, until it transmits wholly and only the light of the soul.

(See II.20; IV.22.)

The movements of consciousness are fwefold. They may be cognizable or non-cognizable, painful or non-painful.

Fluctuations or modifications of the mind may be painful or non-painful, cognizable or non-cognizable. Pain may be hidden in the non-painful state, and the non-painful may be hidden in the painful state. Either may be cognizable or non-cognizable.