Полная версия

Light on the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali

What is soul?

God, Paramatman or Purusa Visesan, is known as the Universal Soul, the seed of all (see 1.24). The individual soul, jivatman or purusa, is the seed of the individual self. The soul is therefore distinct from the self. Soul is formless, while self assumes a form. The soul is an entity, separate from the body and free from the self. Soul is the very essence of the core of one’s being.

Like mind, the soul has no actual location in the body. It is latent, and exists everywhere. The moment the soul is brought to awareness of itself, it is felt anywhere and everywhere. Unlike the self, the soul is free from the influence of nature, and is thus universal. The self is the seed of all functions and actions, and the source of spiritual evolution through knowledge. It can also, through worldly desires, be the seed of spiritual destruction. The soul perceives spiritual reality, and is known as the seer (drsta).

As a well-nurtured seed causes a tree to grow, and to blossom with flowers and fruits, so the soul is the seed of man’s evolution. From this source, asmita sprouts as the individual self. From this sprout springs consciousness, citta. From consciousness, spring ego, intelligence, mind, and the senses of perception and organs of action. Though the soul is free from influence, its sheaths come in contact with the objects of the world, which leave imprints on them through the intelligence of the brain and the mind. The discriminative faculty of brain and mind screens these imprints, discarding or retaining them. If discriminative power is lacking, then these imprints, like quivering leaves, create fluctuations in words, thoughts and deeds, and restlessness in the self.

These endless cycles of fluctuation are known as vrttis: changes, movements, functions, operations, or conditions of action or conduct in the consciousness. Vrttis are thought-waves, part of the brain, mind and consciousness as waves are part of the sea.

Thought is a mental vibration based on past experiences. It is a product of inner mental activity, a process of thinking. This process consciously applies the intellect to analyse thoughts arising from the seat of the mental body through the remembrance of past experiences. Thoughts create disturbances. By analysing them one develops discriminative power, and gains serenity.

When consciousness is in a serene state, its interior components, intelligence, ego, mind and the feeling of ‘I’, also experience tranquillity. At that point, there is no room for thought-waves to arise either in the mind or in the consciousness. Stillness and silence are experienced, poise and peace set in and one becomes cultured. One’s thoughts, words and deeds develop purity, and begin to flow in a divine stream.

Study of consciousness

Before describing the principles of yoga, Patañjali speaks of consciousness and the restraint of its movements.

The verb cit means to perceive, to notice, to know, to understand, to long for, to desire and to remind. As a noun, cit means thought, emotion, intellect, feeling, disposition, vision, heart, soul, Brahman. Cinta means disturbed or anxious thoughts, and cintana means deliberate thinking. Both are facets of citta. As they must be restrained through the discipline of yoga, yoga is defined as citta vrtti nirodhah. A perfectly subdued and pure citta is divine and at one with the soul.

Citta is the individual counterpart of mahat, the universal consciousness. It is the seat of the intelligence that sprouts from conscience, antahkarana, the organ of virtue and religious knowledge. If the soul is the seed of conscience, conscience is the source of consciousness, intelligence and mind. The thinking processes of consciousness embody mind, intelligence and ego. The mind has the power to imagine, think, attend to, aim, feel and will. The mind’s continual swaying affects its inner sheaths, intelligence, ego, consciousness and the self.

Mind is mercurial by nature, elusive and hard to grasp. However, it is the one organ which reflects both the external and internal worlds. Though it has the faculty of seeing things within and without, its more natural tendency is to involve itself with objects of the visible, rather than the inner world.

In collaboration with the senses, mind perceives things for the individual to see, observe, feel and experience. These experiences may be painful, painless or pleasurable. Through their influence, impulsiveness and other tendencies or moods creep into the mind, making it a storehouse of imprints (samskaras) and desires (vAsanas), which create excitement and emotional impressions. If these are favourable they create good imprints; if unfavourable they cause repugnance. These imprints generate the fluctuations, modifications and modulations of consciousness. If the mind is not disciplined and purified, it becomes involved with the objects experienced, creating sorrow and unhappiness.

Patañjali begins the treatise on yoga by explaining the functioning of the mind, so that we may learn to discipline it, and intelligence, ego and consciousness may be restrained, subdued and diffused, then drawn towards the core of our being and absorbed in the soul. This is yoga.

Patañjali explains that painful and painless imprints are gathered by five means: pramana, or direct perception, which is knowledge that arises from correct thought or right conception and is perpetual and true; viparyaya, or misperception and misconception, leading to contrary knowledge; vikalpa, or imagination or fancy; nidra or sleep; and smrti or memory. These are the fields in which the mind operates, and through which experience is gathered and stored.

Direct perception is derived from one’s own experience, through inference, or from the perusal of sacred books or the words of authoritative masters. To be true and distinct, it should be real and self-evident. Its correctness should be verified by reasoned doubt, logic and reflection. Finally, it should be found to correspond to spiritual doctrines and precepts and sacred, revealed truth.

Contrary knowledge leads to false conceptions. Imagination remains at verbal or visual levels and may consist of ideas without a factual basis. When ideas are proved as facts, they become real perception.

Sleep is a state of inactivity in which the organs of action, senses of perception, mind and intelligence remain inactive. Memory is the faculty of retaining and reviving past impressions and experiences of correct perception, misperception, misconception and even of sleep.

These five means by which imprints are gathered shape moods and modes of behaviour, making or marring the individual’s intellectual, cultural and spiritual evolution.

Culture of consciousness

The culture of consciousness entails cultivation, observation, and progressive refinement of consciousness by means of yogic disciplines. After explaining the causes of fluctuations in consciousness, Patañjali shows how to overcome them, by means of practice, abhyasa, and detachment or renunciation, vairagya.

If the student is perplexed to find detachment and renunciation linked to practice so early in the Yoga Sutras, let him consider their symbolic relationship in this way. The text begins with atha yoganusAsanam. AnusAsanam stands for the practice of a disciplined code of yogic conduct, the observance of instructions for ethical action handed down by lineage and tradition. Ethical principles, translated from methodology into deeds, constitute practice. Now, read the word ‘renunciation’ in the context of sutra I.4: ‘At other times, the seer identifies with the fluctuating consciousness.’ Clearly, the fluctuating mind lures the seer outwards towards pastures of pleasure and valleys of pain, where enticement inevitably gives rise to attachment. When mind starts to drag the seer, as if by a stout rope, from the seat of being towards the gratification of appetite, only renunciation can intervene and save the sadhaka by cutting the rope. So we see, from sutras I.1 and I.4, the interdependence from the very beginning of practice and renunciation, without which practice will not bear fruit.

Abhyasa is a dedicated, unswerving, constant, and vigilant search into a chosen subject, pursued against all odds in the face of repeated failures, for indefinitely long periods of time. Vairagya is the cultivation of freedom from passion, abstention from worldly desires and appetites, and discrimination between the real and the unreal. It is the act of giving up all sensuous delights. Abhyasa builds confidence and refinement in the process of culturing the consciousness, whereas vairagya is the elimination of whatever hinders progress and refinement. Proficiency in vairagya develops the ability to free oneself from the fruits of action.

Patañjali speaks of attachment, non-attachment, and detachment. Detachment may be likened to the attitude of a doctor towards his patient. He treats the patient with the greatest care, skill and sense of responsibility, but does not become emotionally involved with him so as not to lose his faculty of reasoning and professional judgement.

A bird cannot fly with one wing. In the same way, we need the two wings of practice and renunciation to soar up to the zenith of Soul realization.

Practice implies a certain methodology, involving effort. It has to be followed uninterruptedly for a long time, with firm resolve, application, attention and devotion, to create a stable foundation for training the mind, intelligence, ego and consciousness.

Renunciation is discriminative discernment. It is the art of learning to be free from craving, both for worldly pleasures and for heavenly eminence. It involves training the mind and consciousness to be unmoved by desire and passion. One must learn to renounce objects and ideas which disturb and hinder one’s daily yogic practices. Then one has to cultivate non-attachment to the fruits of one’s labours.

If abhyasa and vairagya are assiduously observed, restraint of the mind becomes possible much more quickly. Then, one may explore what is beyond the mind, and taste the nectar of immortality, or Soul-realization. Temptations neither daunt nor haunt one who has this intensity of heart in practice and renunciation. If practice is slowed down, then the search for Soul-realization becomes clogged and bound in the wheel of time.

Why practice and renunciation are essential

Avidya (ignorance) is the mother of vacillation and affliction. Patañjali explains how one may gain knowledge by direct and correct perception, inference and testimony, and that correct understanding comes when trial and error ends. Here, both practice and renunciation play an important role in gaining spiritual knowledge.

Attachment is a relationship between man and matter, and may be inherited or acquired.

Non-attachment is the deliberate process of drawing away from attachment and personal affliction, in which, neither binding oneself to duty nor cutting oneself off from it, one gladly helps all, near or far, friend or foe. Non-attachment does not mean drawing inwards and shutting oneself off, but involves carrying out one’s responsibilities without incurring obligation or inviting expectation. It is between attachment and detachment, a step towards detachment, and the sadhaka needs to cultivate it before thinking of renunciation.

Detachment brings discernment: seeing each and every thing or being as it is, in its purity, without bias or self-interest. It is a means to understand nature and its potencies. Once nature’s purposes are grasped, one must learn to detach onself from them to achieve an absolute independent state of existence wherein the soul radiates its own light.

Mind, intelligence and ego, revolving in the wheel of desire (kama), anger (krodha), greed (lobha), infatuation (moha), pride (mada) and malice (matsarya), tie the sadhaka to their imprints; he finds it exceedingly difficult to come out of the turmoil and to differentiate between the mind and the soul. Practice of yoga and renunciation of sensual desires take one towards spiritual attainment.

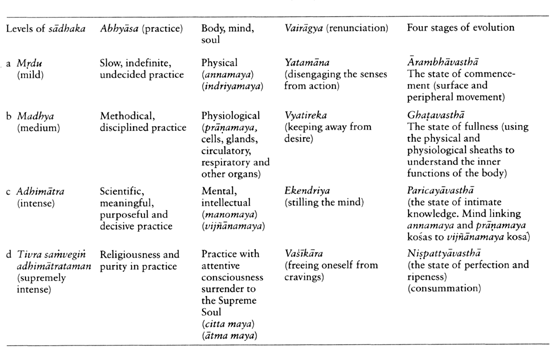

Practice demands four qualities from the aspirant: dedication, zeal, uninterrupted awareness and long duration. Renunciation also demands four qualities: disengaging the senses from action, avoiding desire, stilling the mind and freeing oneself from cravings.

Practitioners are also of four levels, mild, medium, keen and intense. They are categorized into four stages: beginners; those who understand the inner functions of the body; those who can connect the intelligence to all parts of the body; and those whose body, mind and soul have become one. (See table 1.)

Effects of practice and renunciation

Intensity of practice and renunciation transforms the uncultured, scattered consciousness, citta, into a cultured consciousness, able to focus on the four states of awareness. The seeker develops philosophical curiosity, begins to analyse with sensitivity, and learns to grasp the ideas and purposes of material objects in the right perspective (vitarka). Then he meditates on them to know and understand fully the subtle aspects of matter (vicara). Thereafter he moves on to experience spiritual elation or the pure bliss (ananda) of meditation, and finally sights the Self. These four types of awareness are collectively termed samprajñata samadhi or samprajñata samapatti. Samapatti is thought transformation or contemplation, the act of coming face to face with oneself.

From these four states of awareness, the seeker moves to a new state, an alert but passive state of quietness known as manolaya. Patañjali cautions the sadhaka not to be caught in this state, which is a crossroads on the spiritual path, but to intensify his sadhana to experience a still higher state known as nirbija samadhi or dharma megha samadhi. The sadhaka may not know which road to follow beyond manolaya, and could be stuck there forever, in a spiritual desert. In this quiet state of void, the hidden tendencies remain inactive but latent. They surface and become active the moment the alert passive state disappears. This state should therefore not be mistaken for the highest goal in yoga.

This resting state is a great achievement in the path of evolution, but it remains a state of suspension in the spiritual field. One loses body consciousness and is undisturbed by nature, which signifies conquest of matter. If the seeker is prudent, he realizes that this is not the aim and end, but only the beginning of success in yoga. Accordingly, he further intensifies his effort (upaya pratyaya) with faith and vigour, and uses his previous experience as a guide to proceed from the state of void or loneliness, towards the non-valid state of aloneness or fullness, where freedom is absolute.

Table 1: Levels of sadhaka, levels of sadhana and stages of evolution

If the sadhaka’s intensity of practice is great, the goal is closer. If he slackens his efforts, the goal recedes in proportion to his lack of willpower and intensity.

Universal Soul or God (Isvara, Purusa Visesan or Paramatman)

There are many ways to begin the practice of yoga. First and foremost, Patañjali outlines the method of surrender of oneself to God (Isvara). This involves detachment from the world and attachment to God, and is possible only for those few who are born as adepts. Patañjali defines God as the Supreme Being, totally free from afflictions and the fruits of action. In Him abides the matchless seed of all knowledge. He is First and Foremost amongst all masters and teachers, unconditioned by time, place and circumstances.

His symbol is the syllable AUM. This sound is divine: it stands in praise of divine fulfilment. AUM is the universal sound (sabda brahman). Philosophically, it is regarded as the seed of all words. No word can be uttered without the symbolic sound of these three letters, a, u and m. The sound begins with the letter a, causing the mouth to open. So the beginning is a. To speak, it is necessary to roll the tongue and move the lips. This is symbolized by the letter u. The ending of the sound is the closing of the lips, symbolized by the letter m..AUM represents communion with God, the Soul and with the Universe.

AUM is known as pranava, or exalted praise of God. God is worshipped by repeating or chanting AUM, because sound vibration is the subtlest and highest expression of nature. Mahat belongs to this level. Even our innermost unspoken thoughts create waves of sound vibration, so AUM represents the elemental movement of sound, which is the foremost form of energy. AUM is therefore held to be the primordial way of worshipping God. At this exalted level of phenomenal evolution, fragmentation has not yet taken place. AUM offers complete praise, neither partial nor divided: none can be higher. Such prayer begets purity of mind in the sadhaka, and helps him to reach the goal of yoga. AUM, repeated with feeling and awareness of its meaning, overcomes obstacles to Self-Realization.

The obstacles

The obstacles to healthy life and Self-Realization are disease, indolence of body or mind, doubt or scepticism, carelessness, laziness, failing to avoid desires and their gratification, delusion and missing the point, not being able to concentrate on what is undertaken and to gain ground, and inability to maintain concentration and steadiness in practice once attained. They are further aggravated through sorrows, anxiety or frustration, unsteadiness of the body, and laboured or irregular breathing.

Ways of surmounting the obstacles and reaching the goal

The remedies which minimize or eradicate these obstacles are: adherence to single-minded effort in sadhana, friendliness and goodwill towards all creation, compassion, joy, indifference and non-attachment to both pleasure and pain, virtue and vice. These diffuse the mind evenly within and without and make it serene.

Patañjali also suggests the following methods to be adopted by various types of practitioners to diminish the fluctuations of the mind.

Retaining the breath after each exhalation (the study of inhalation teaches how the self gradually becomes attached to the body; the study of exhalation teaches non-attachment as the self recedes from the contact of the body; retention after exhalation educates one towards detachment); involving oneself in an interesting topic or object contemplating a luminous, effulgent and sorrowless light; treading the path followed by noble personalities; studying the nature of wakefulness, dream and sleep states, and maintaining a single state of awareness in all three; meditating on an object which is all-absorbing and conducive to a serene state of mind.

Effects of practice

Any of these methods can be practised on its own. If all are practised together, the mind will diffuse evenly throughout the body, its abode, like the wind which moves and spreads in space. When they are judiciously, meticulously and religiously practised, passions are controlled and single-mindedness develops. The sadhaka becomes highly sensitive, as flawless and transparent as crystal. He realizes that the seer, the seeker and the instrument used to see or seek are nothing but himself, and he resolves all divisions within himself.

This clarity brings about harmony between his words and their meanings, and a new light of wisdom dawns. His memory of experiences steadies his mind, and this leads both memory and mind to dissolve in the cosmic intelligence.

This is one type of samadhi, known as sabija samadhi, with seed, or support. From this state, the sadhaka intensifies his sadhana to gain unalloyed wisdom, bliss and poise. This unalloyed wisdom is independent of anything heard, read or learned. The sadhaka does not allow himself to be halted in his progress, but seeks to experience a further state of being: the amanaskatva state.

If manolaya is a passive, almost negative, quiet state, amanaskatva is a positive, active state directly concerned with the inner being, without the influence of the mind. In this state, the sadhaka is perfectly detached from external things. Complete renunciation has taken place, and he lives in harmony with his inner being, allowing the seer to shine brilliantly in his own pristine glory.

This is true samadhi: seedless or nirbija samadhi.

II: Sadhana Pada

Why did Patañjali begin the Yoga Sutras with a discussion of so advanced a subject as the subtle aspect of consciousness? We may surmise that intellectual standards and spiritual knowledge were then of a higher and more refined level than they are now, and that the inner quest was more accessible to his contemporaries than it is to us.

Today, the inner quest and the spiritual heights are difficult to attain through following Patañjali’s earlier expositions. We turn, therefore, to this chapter, in which he introduces kriyayoga, the yoga of action. Kriyayoga gives us the practical disciplines needed to scale the spiritual heights.

My own feeling is that the four padas of the Yoga Sutras describe different disciplines of practice, the qualities or aspects of which vary according to the development of intelligence and refinement of consciousness of each Sadhaka.

Sadhana is a discipline undertaken in the pursuit of a goal. Abhyasa is repeated practice performed with observation and reflection. Kriya, or action, also implies perfect execution with study and investigation. Therefore, sadhana, abhyasa, and kriya all mean one and the same thing. A sadhaka, or practitioner, is one who skilfully applies his mind and intelligence in practice towards a spiritual goal.

Whether out of compassion for the more intellectually backward people of his time, or else foreseeing the spiritual limitations of our time, Patañjali offers in this chapter a method of practice which begins with the organs of action and the senses of perception. Here, he gives those of average intellect the practical means to strive for knowledge, and to gather hope and confidence to begin yoga: the quest for Self-Realization. This chapter involves the sadhaka in the art of refining the body and senses, the visible layers of the soul, working inwards from the gross towards the subtle level.

Although Patañjali is held to have been a self-incarnated, immortal being, he must have voluntarily descended to the human level, submitted himself to the joys and sufferings, attachments and aversions, emotional imbalances and intellectual weaknesses of average individuals, and studied human nature from its nadir to its zenith. He guides us from our shortcomings towards emancipation through the devoted practice of yoga. This chapter, which may be happily followed for spiritual benefit by anyone, is his gift to humanity.

Kriyayoga, the yoga of action, has three tiers: tapas, svadhyaya and Isvara pranidhana. Tapas means burning desire to practise yoga and intense effort applied to practice. Svadhyaya has two aspects: the study of scriptures to gain sacred wisdom and knowledge of moral and spiritual values; and the study of one’s own self, from the body to the inner self. Isvara pranidhana is faith in God and surrender to God. This act of surrender teaches humility. When these three aspects of kriyayoga are followed with zeal and earnestness, life’s sufferings are overcome, and samadhi is experienced.