Полная версия

Extreme Nature

Extreme Nature

Mark Cawardine

With Rosamund Kidman Cox

Copyright

HarperCollins Publishers Ltd.

77–85 Fulham Palace Road

London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2005

Text © 2005 Mark Carwardine

Commissioning Editor: Helen Brocklehurst

Art Director: Mark Thomson

Editor: Rosamund Kidman-Cox

Design and layout: Richard Marston

Proofreader: Kate Parker

Index: Hilary Bird

Editorial Assistant: Julia Koppitz

Colour reproduction by Dot Gradation, Essex

Mark Carwardine asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007207688

Ebook Edition © OCTOBER 2014 ISBN: 9780007596614

Version: 2014-10-13

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Introduction

Extreme Abilities

Extreme Movement

Extreme Growth

Extreme Families

Keep Reading

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher

Introduction

Extreme Nature is about some of the most intriguing, supernatural, out of the ordinary and extreme plants and animals on the planet. A fish that can change sex, a frog that gives birth through its mouth and a flower that smells so bad it makes people faint are in the motley collection of weird and wonderful creatures included in the book.

If proof were ever needed that fact really is stranger than fiction, then look no further than the natural world. Did you know, for example, that a bombardier beetle can blast a chemical spray that’s as hot as boiling water? Are you aware that a castor bean produces a toxin 6,000 times more deadly than cyanide? And have you ever wondered about the three-toed sloth, which has just two modes of being: asleep and not quite asleep?

It would have been hard for a science fiction writer to dream up some of the most bizarre creatures and wacky behaviour described in this book. Imagine an animal that squirts up to a quarter of its own blood at its predators – that’s the Texas horned lizard. There is a frog that can withstand being frozen to –270°C (–454°F) and a moth with a 35cm (14in) tongue. A fish that can inflate itself to become a spine-covered sphere three times its original size may sound like a character from The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, but it really does exist, in tropical seas around the world, in the form of the pufferfish.

One of the richest environments for such peculiar and eccentric wildlife is the sea. This is where scientists first discovered the coelacanth, for example – a strange-looking fish that was thought to have gone extinct 65 million years ago, but is now known to be alive and well and living in the western Indian Ocean. The sea is where we first set eyes on a remarkable octopus that lives a life of deception, by disguising itself as anything from a flounder or a jellyfish to a sea snake. And in the cold, dark ocean depths scientists have found shrimp-like creatures thriving 11 km (6.8 miles) below sea level. But the sea is also the most unexplored region of the world and studying its wildlife can be about as difficult and challenging as exploring outer space. Even now, there are probably huge animals lurking beneath the ocean waves as yet unseen by human eyes – and untold numbers of smaller ones. But with the help of space-age research techniques and equipment, such as deep-sea submersibles and remote-access vehicles, we are just beginning to understand the true extent of alien-like life on our own planet.

There are more outlandish creatures to discover on land, too, though many of them are likely to be the natural world’s tiddlers and relatively hard to find. But the fact that we’ve already unearthed plants that eat animals, insects capable of walking on water and frogs with baggy skin just makes scientists determined to search for new species of plants and animals and ever-more extravagant forms of behaviour. It’s hard not to wonder what secrets have yet to be unravelled in the treetops, deep underground, in hidden corners of remote tropical rainforests, or under the glare of a microscope.

Extreme Nature was written with the invaluable help of over 150 such scientists working in all corners of the globe. With their generous assistance, in just a few sentences it’s been possible to summarise some of the highlights of many years, sometimes decades, of research. Thanks to them, if you’ve ever wondered which animal has the best colour vision, if a millipede really does have a thousand legs, how fast a falcon can swoop, or which is the world’s most dangerous snake, this is the place to look.

Any study of extreme nature is inevitably full of surprises, and when it comes to superlatives, there is always another record-breaker just around the corner. But while there’s little doubt that few of the records we’ve included are absolutes, in one way or another all animals and plants have something exceptional about them that deserves our attention. It’s certainly been enormous fun corresponding with so many experts in so many different fields and, with their guidance, making the final selection.

Ultimately, the aim of the book is simply to revel in these other-worldly creatures and their outlandish behaviour. We hope you enjoy being wowed by some of their exploits.

Extreme Abilities

Most devious plant · Strangest boxer · Most explosive defence · Most poisonous animal · Most ingenious tool-maker · Most gruesome partnership · Best electro-detector · Stickiest skin · Deadliest plant · Biggest blood-sucker · Keenest sense of smell · Most enthusiastic singer · Most gruesome tongue · Most inquisitive bird · Biggest drug-user · Most painful stinger · Slipperiest plant · Heaviest drinker · Best mimic · Most formidable killer · Best architect · Most painful tree · Loudest bird call · Deadliest drooler · Most sensitive slasher · Smelliest plant · Most impressive comeback · Hottest animal · Most shocking animal · Coldest animal · Most talkative animal · Most bizarre defence · Smelliest animal · Slimiest animal · Keenest hearing · Stickiest spitter · Best colour vision · Most dangerous snake

Most devious plant

NAMEghost orchid Epipogium aphyllumLOCATIONNorth and Central Europe east to JapanABILITYcheating a fungus

© Jeffrey Wood/Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

The natural world as we know it is built on partnerships. But in all societies there are cheats, and plants are no exception. Most green plants would be unable to exist without the help of fungi, which provide them with food-exchange partnerships. In fact, the invasion of the land by plants – algae – was probably only made possible by such partnerships. It has even been suggested that early land plants developed roots just so they could join forces with the fungal roots, or hyphae.

Most plants are proper partners, giving the carbohydrates they manufacture with their chlorophyll. Some, notably orchids, have such a close partnership that they don’t even bother to produce proper food packages to accompany their embryos into the world, instead relying on fungi in the soil to provide the food needed for germination and early growth. This allows an orchid to produce lightweight, microscopic seeds – millions of them.

Some orchids, however, have become cheats: they use fungi that have partnerships with trees, and they never give anything in exchange. Via fungal hyphae, these orchid vampires tap into the trees, siphoning off nutrients. The give-away is often the fact that they have stopped producing chlorophyll and so aren’t green but a rather sickly pinkish cream, like the ghost orchid, or brown, like the bird’s-nest orchid. Some, such as western coralroot, are blood red or even purple. The drawback is that, without the fungus, the orchid will die. And one day a fungus might just evolve a way to get its own back.

Strangest boxer

NAMEboxer crab, or pom pom crab, Lybia speciesLOCATIONIndian and Pacific OceansABILITYpacking a punch with anemone gloves

© Roger Steene/imagequest3d.com

Mutual relationships in the sea are common. A famous one is between a hermit crab and an anemone, where the former gains protection from the anemone’s stinging nematocysts, and the latter gets leftover food. Boxer crabs seem to have taken this a stage further. These tiny crabs – their carapace measures just 1.5cm (0.6in) – are prey to many animals. Their defence is to wield minute, stinging anemones on specialised claws. A jab with a ‘glove’ can cause pain (even to a human) or death and seems an effective defence – one boxer has even been observed seeing off a blue-ringed octopus. The anemones are also used in crab-to-crab boxing. But such fights are ritualistic, and boxing opponents hardly ever touch each other with their anemones, grappling instead with their walking legs.

When a growing boxer has to moult, it must put down its anemones and then grab them again when its new carapace (outer covering) has hardened. If it then finds itself with just one anemone, it merely breaks it in two, and the anemone obligingly duplicates itself. Surprisingly, the anemones don’t seem to object to being picked up or to being brandished in the face of a predator – at least, one hasn’t been seen trying to escape. And it’s hard to tell what it gets in return other than free travel, but since the boxer uses the anemone to stun food animals, maybe the anemone gets enough leftovers to make life on the claw worth it.

Most explosive defence

NAMEbombardier beetles Carabidae familyLOCATIONon every continent except AntarcticaABILITYmixing chemicals to create an explosion

© Thomas Eisner & Daniel Aneshansley/Cornell University

In the world of insects, ants can overcome almost anything. But they don’t always have it their own way. Bombardier beetles deliver an anti-ant surprise that is positively explosive. An ant, a spider or any other predator that, say, clamps on to a beetle’s leg with hostile intent instantly finds itself blasted with a chemical spray that’s as hot as boiling water.

So how does a small, cold-blooded creature manage to do this? Pure chemistry: in the rear of its abdomen are two identical glands lying side by side and opening at the abdominal tip. Each has an inner chamber containing hydrogen peroxide and hydroquinones and an outer one with catalase and peroxidase. When chemicals in the inner chamber are forced through the outer one, the chemicals react together, and the beetle has effectively created a bomb.

The resulting vapour, now containing the irritants known as p-benzoquinones, explodes from the end of the abdomen with a bang that’s audible to a human and a temperature that’s scalding to the would-be predator. What’s more, the beetle can rotate its abdomen through 270 degrees in any direction, so that it can aim with absolute precision, and if 270 degrees isn’t enough, it can shoot over its back, hitting a pair of reflectors that will ricochet the spray at the extra angle needed. Scientists find bombardiers fascinating because they’re the only animals known to mix chemicals to create an explosion.

Most poisonous animal

NAMEgolden poison-dart frog Phyllobates terribilisLOCATIONPacific rainforests of Colombia, South AmericaABILITYproducing the most deadly poison of any animal

© Chris Mattison/FLPA

This tiny frog uses toxic chemicals as a defence in its body and is therefore technically poisonous (venomous animals inject toxins via a weapon – a tail, fang, spine, spur or tooth). The toxin is effective only when the frog is attacked, and since the frog doesn’t want to be harmed, it sports a brilliant yellow or orange colour to warn predators of extreme danger.

In fact, this most poisonous of frogs is possibly the most poisonous animal in the world. The toxin is in its skin – you can die even by touching it – and there is enough in the skin of one animal to kill up to 100 people. Though the frog has been known to science only since 1978, inhabiting just one area in Colombia, the Chocó indians have known about it for generations, using its skin-gland secretions to poison their blowgun darts and kill animals in seconds.

The golden poison-dart frog gets most of its batrachotoxin (meaning frog poison) from other animals, probably small beetles, which in turn get it from plant sources. Captive-bred frogs, by comparison, never become toxic, presumably because they aren’t fed toxic insects. The frog is active in the day, having few predators except a snake, that has become immune to the toxin. Surprisingly, birds have been discovered in New Guinea with the same batrachotoxin in their skin and feathers. The likely link has been tracked down to a small beetle, similar to the New World beetles, which also contains batrachotoxins.

Most ingenious tool-maker

NAMENew Caledonian crow Corvus moneduloidesLOCATIONPacific island of New CaledoniaABILITYthinking up ways to get at hard-to-reach food

© Ron Toft

Quite a few non-human animals, from sea otters to woodpecker finches, use tools and sometimes even craft them. It’s usually assumed that the animal that is best at this is our nearest relative, the chimpanzee. Chimps use rocks to crack nuts and cut and fashion twigs or blades of grass to fish in mounds for termites. These are ‘cultural’ skills, practised only by certain groups of chimps and taught to youngsters. The skills are certainly sophisticated: an anthropologist once spent several months with a group of chimps trying to learn the art of termite fishing and finally achieved the proficiency, he reckoned, of a four-year-old chimp novice.

For pure innate, instant ingenuity, though, it would be hard to top the New Caledonian crow. In an experiment in a lab, meat was put in a little basket at the bottom of a perspex cylinder – and a female crow, Betty, was given a straight piece of wire. Holding the wire in her beak, she tried to pull the basket up, and failed. Then she took the wire to the side of the box holding the cylinder, poked it behind some tape and bent the end into a hook. She went back, hooked the basket, and got the meat. When the experiment was repeated, Betty did roughly the same thing, but with the addition of two different tool-making techniques. In the wild, New Caledonia crows make food-hooks out of twigs, by snipping off all but one protuberance. But bending a piece of wire … how would a crow know?

Most gruesome partnership

NAMEluminescent bacteria Photorhabdus luminescens meets nematode Heterorhabditis bacteriophoraLOCATIONinside a caterpillar or maggotABILITYcombining forces to eat larvae alive

© Randy Gaugler

This is a slow and horrible way to die. A worm-like creature, a nematode, goes on the hunt by squirming through the soil in search of an unsuspecting insect grub, or larva. It’s not particularly fussy and likes anything from a weevil to a fly maggot, but it may take months to find a suitable victim. When it does, it penetrates the cuticle of the larva, either through an opening such as a breathing pore or by hacking a hole with its special ‘tooth’. Once inside, it sets free more than a hundred bacteria from inside its gut, which start producing deadly toxins, digestive enzymes and antibiotics.

The bacteria are luminescent, and as they multiply, the grub takes on a deathly glow. The nematode then starts feeding on the bacteria and the remains of the grub corpse, which is kept free from other competing microorganisms by the antibiotics. Finally, it changes into a hermaphrodite female, laying eggs in the cadaver that hatch into both male and female nematodes.

Yet more of her eggs develop inside her, and when they hatch, the juvenile nematodes eat their mother. They then mate and produce their own eggs. It’s at this point, two weeks later, that the grub finally breaks up and thousands of young nematodes (each carrying the bacteria in their guts) exit into the soil. The bacteria and the nematode can’t exist without each other – a gruesome partnership but one that humans have joined, helping the little nematodes spread by deliberately releasing them to hunt down garden pests.

Best electro-detector

NAMEgreat hammerhead Sphyrna mokarranLOCATIONtropical and warm temperate seasSKILLhunting with electricity

© James D Watt/imagequest3d.com

All sharks can, to some extent, detect other creatures by sensing the minuscule amount of electricity they create simply by virtue of being alive. In most sharks, this sense is principally an adjunct to more dominant senses (usually hearing, smell and vision) and is particularly important in the final split-second of an attack. But for hammerheads, it’s the main thing, and it could be one reason why their heads are shaped in the curious way they are.

Sharks have special electrical receptors – hundreds of tiny, dark pores called ‘ampullae of Lorenzini’ – which are filled with a conductive gel that transfers electrical impulses to a nerve end in each pore. Ordinary sharks have these all over the snout and lower jaw, forming a curious pattern of dark holes resembling a sparse five-o’clock shadow.

But hammerheads also have a mass of them across the underside of their oblong heads, which scan across the sandy sea-bottom like metal detectors, searching for prey animals that can’t be found in any other way – creatures such as stingrays and flatfish that bury themselves, lie still and usually have no appreciable scent.

The hammerheads are able to detect the slight direct currents caused by interaction between the bodies of their prey and the seawater and the even slighter alternating currents caused by muscle contractions around an animal’s heart. The eight species of hammerhead can sense it better than most other sharks, and the biggest of these, the great hammerhead, which measures up to 6m (20ft) long, may be able to sense it best of all.

Stickiest skin

NAMEholy-cross, crucifix or Catholic toad Notaden bennettiLOCATIONAustraliaABILITYproducing a super ‘superglue’

© Ken Griffiths/ANTphoto.com

Some of the world’s strangest creatures are found in Australia – a continent of extremes giving rise to extreme adaptations. The holy-cross toad lives where many other amphibians can’t: in hot, harsh areas inland, where droughts may last for several years. It uses its strong back legs to burrow down in the soil, where it sits out the heat of the day, and when drought sets in, it survives by digging a chamber a metre or so underground in which it aestivates (becomes dormant), emerging only when the rains return.

Like its close toad relatives, the holy-cross also has unique glands in its skin. If it is disturbed or distressed, these release a special secretion that turns into glue. The glue hardens in seconds and has a tensile strength five times that of other natural glues. This is particularly useful should ants attack, as even the biggest immediately get stuck to the toad’s skin. And since, like all frogs and toads, it sheds its skin and eats it about once a week, the holy-cross toad has the pleasure of swallowing the ants that attack it.

Scientists in Australia are now trying to produce an artificial glue as good as the toad’s. Holy-cross toad glue will stick plastic, glass, cardboard and even metal together. More importantly, it can repair splits in cartilage and other body tissues and therefore might prove to be a miracle adhesive that will help surgeons repair the most difficult of injuries.

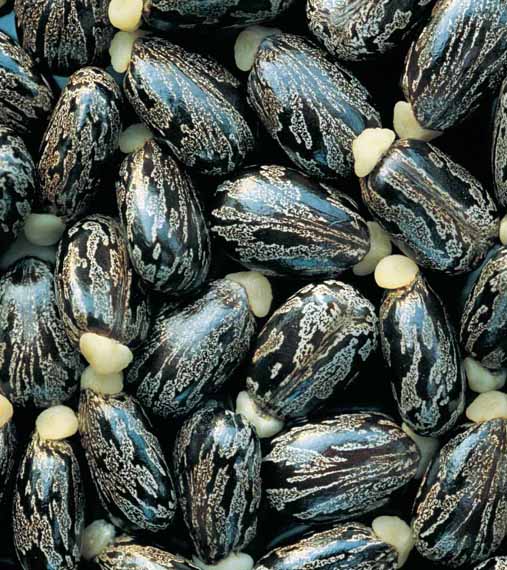

Deadliest plant

NAMEcastor bean Ricinus communisLOCATIONworldwide; origin unknown, but probably EthiopiaABILITYproducing the deadly poison ricin

© Haroldo Palo Jr/NHPA

The castor bean plant produces possibly the most deadly plant toxin, 6,000 times more deadly than cyanide, but it has also been known for thousands of years as a wonder plant. The secret and the poison both lie in the seed. More than 50 per cent of it comprises a rich oil, but to protect it from being eaten is ricin, a protein toxic to almost all animals (lesser quantities of ricin occur in the leaves). The poison, once ingested, inactivates the key protein-making elements of a cell without which it can’t maintain itself and dies.

For humans, death is prolonged, ending in convulsions and failure of the liver and other organs. There is no known antidote. The most usual cause of poisoning comes from accidentally eating seeds, but ricin can be administered in aerosol form, in food or water, or injected, as in the famous case of a dissident Bulgarian journalist. While waiting at a bus stop at Waterloo station in London, in 1978, Georgi Markov was murdered by being stabbed with an umbrella that injected a pellet containing ricin. Widely available and easily produced, ricin could be used for biological warfare.