Полная версия

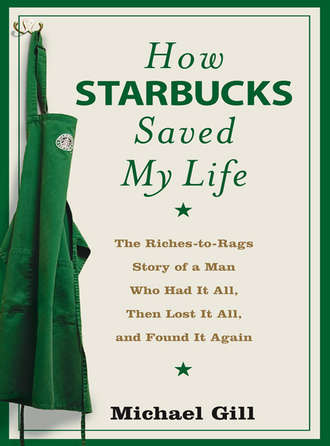

How Starbucks Saved My Life

“Let’s share a cup of coffee,” she said, guiding me over to a little table in the corner. “Sit here, I will bring you a sample.”

Maybe this was just Crystal’s public, professional attitude, but I was grateful for it. She seemed much friendlier than on the phone. Perhaps, I thought, she had come to terms with hiring me and did not hate herself or me for taking this chance.

Soon I was sitting down in a small corner with Crystal and sipping a delicious cup of Sumatra. “This is a coffee that is known as having an ‘earthy’ taste … but I call it dirty.” Crystal laughed, and I laughed too. Today Crystal had her hair up under a Starbucks cap, making her look very sophisticated, even glamorous. Two bright diamond earrings caught the light.

Maybe it was the coffee, more likely it was Crystal’s ability to put me at my ease, but I was feeling a lot better.

Still, I was a long way from being comfortable. Out of nowhere, I had a sudden image of myself in a long past life, basking in the comfort of family and friends on a dock on a lake in Connecticut. Now that image of laughing and lounging so comfortably beneath a warming sun seemed like several lifetimes ago. The lake I had grown up on was protected by thousands of acres of private forest. It kept out the reality of a harsher world and surrounded me with fun and privilege.

I remembered as a young boy throwing apples at the poet Ezra Pound. Jay Laughlin, Pound’s publisher, owned the camp next door and had brought Pound down to the lake for the day. Pound sat like a kind of statue at the end of the dock. At one point he rolled up his suit pants and dangled his white legs into the water, still not speaking. His legs looked like the white underbelly of a frog. There was something about Pound’s proud strangeness that got to my young cousins and me. We picked up some apples we had been eating and started throwing them at him, missing him but sending up water to splash against his dark, foreign clothes.

Ezra Pound did not move or speak. My father laughed and kind of encouraged us in our behavior. My father had written a bestselling book, Here at The New Yorker, about his years at the magazine. In the opening, he had stated his philosophy: “The first rule of life is to have a good time. There is no second rule.” Having a good time for my father meant upsetting apple carts. He had no love for Pound’s politics and enjoyed the scene.

My father had won his place on this lake by marrying into my mother’s family, who had vacationed there for a hundred years. My father brought new money, earned by his Irish immigrant father, into her Mayflower ancestry. At the lake there was a powerful combustion of gentle Wasp politeness meeting up with my father’s purposefully provocative Celtic rebel style. With a kind of self-righteous abandon my father joyously spent the money his father had worked so hard to earn.

“It is better to spend your money while you are still alive,” my father would declare, his black eyes flashing with a kind of devil-may-care enthusiasm, seeming to mock his own father’s hard-won acquisition and those uptight Yankees around the lake who pinched every penny.

My father loved to speak, he loved to write, and he loved, above all, to be the center of attention at parties. “Everything happens at parties,” he would say. So there was a constant party on our dock at this exclusive, rustic lake.

My father was a spendthrift with his time as with all his many talents. He gave himself away to so many that there was never enough time at home for me. Never enough time for one-on-one, for father and son. When I was grown, and I moved away from home, he invited me to his parties, and that is the only way we saw each other. When he died, my need to go to parties died as well.

Now I found myself sipping coffee with Crystal—worlds away from the parties during those summers on that exclusive lake—yet as I laughed with her, I could actually feel my heart become a little lighter and my spirits rise a bit. This reality surprised me. Maybe it was the caffeine in this powerful coffee. But I also had to admit that I felt at ease in this totally new scene—having coffee in a crowded, upbeat bar as a way of beginning a new job. It was all so bizarre and foreign, like Alice through the looking glass. Or Michael Gates Gill breaking through to another place and class to find it wasn’t so scary after all. I was stepping out from my old status quo, and as a direct result, I felt better than I had in days. Or weeks. Or months.

It was crazy … but maybe, I hoped, there was a method in this madness.

Crystal’s voice broke through my daydream. “Mike, it is important you learn the differences in these coffees.” I no longer had the luxury of time for philosophical self-concern. The bell had rung. I was in the ring. It was time to get involved in minute-by-minute efforts rather than heavy contemplation. Keeping up with customers’ orders was my new job. I had to give up spending so much time thinking about the past and what I had lost. It was going to be a big challenge just to keep up with the present.

I was about to discover that at Starbucks it was not about me—it was about serving others.

Crystal had a serious look on her face and launched into a lecture as though I were some eager student of coffee lore: “Sumatra coffee is from Indonesia; the Dutch brought it there hundreds of years ago, and it’s part of a whole category of coffees we call ‘bold.’”

“We” again, I noticed, thinking back to Linda White and her “we” when she had fired me. Crystal could do the same.

“This is the way we welcome all new Partners,” Crystal explained, leaning forward toward me as though to confide a great personal secret. “We believe that coffee is our business. Starbucks Coffee is our name. So we welcome all new Partners with coffee sampling and coffee stories.”

Crystal sat back with a smile, and I smiled back at her. Her face now seemed so positive and cheerful. Even her brown eyes, which could be so cold, now seemed to sparkle with a kind of happy interest. It had become clear to me as she talked that she was intelligent and even passionate. At least about the coffee business. And I felt that maybe—just maybe—Crystal really was going to give me a chance to prove myself.

As I sampled the rich Sumatra brew, I was beginning to feel that I could handle this part of the Starbucks business. I loved coffee; I loved learning about the history of things. I glanced over at the Partners behind the counter, all working hard yet seeming to have a great time. While they were all so young, and while there was not a white face in the bunch, maybe, I told myself, I should be, like the coffee I was drinking, part of the “bold” category.

Then the store door swung open. In stepped a scowling African-American guy, well over six feet tall with bulging muscles under a black T-shirt. He was wearing a do-rag wrapped tight around his head that, to my eyes, made him look like a modern pirate. He had a mustache and some sort of hair thing happening on his chin. He was the kind of person that in the past I had crossed the street to avoid.

Crystal called to him, “Hey, Kester, come over and meet Mike.”

Kester walked slowly over to our table. I noticed a bruise on his forehead. He reached out a big hand.

“Hi, Mike,” he said with a low baritone. And then he smiled. His smile transformed his whole face. Immediately, I felt welcomed. In fact, he seemed much warmer than Crystal. Why? Was this because he was much more confident he could handle me? Old white guys definitely didn’t bother him.

“Kester, where did you get that?” Crystal said, pointing at his forehead.

“Soccer.”

“Soccer?”

“Yeah, some of my friends from Columbia got me into the game…. It turns out they think I’m pretty good. A natural.” Kester laughed when he said that.

But Crystal quickly got back to the business at hand. Her face took on what I was coming to know as her hard, professional look. I got a sense Crystal always liked to be in control. “Mike is a new Partner,” she explained to Kester, “and I was wondering if you could do me a favor…. Would you be willing to be his training coach?”

I was to learn that nobody at Starbucks ever ordered anyone to do anything. It was always: “Would you do me a favor?” or something similar.

“Sure,” Kester replied, “I’ll change and be right back.”

After he left, Crystal told me, leaning forward in her confidential way, “Kester never smiled until he started working here. He was leader of a group of bad …” She stopped, seeming to be conscious of telling me too much. She leaned back, adjusting her hair. She had so many moods. Confiding. Confidential. Serious. Cheerful. Professional. Wary. Now she was wary again.

Kester returned, dressed in a green apron and black Starbucks cap, yet still looked pretty intimidating … until he smiled. Crystal got up and gave him her seat.

“I’ll bring you two some more coffee.”

Crystal returned with a cup of Verona for each of us and some espresso brownies. I was surprised by the enthusiastic way she served us. I had never served anything to any subordinate in all my years in corporate life. But Crystal seemed to be genuinely enjoying the experience. She and Starbucks seemed to have turned the traditional corporate hierarchy upside down.

She launched into a detailed description of Verona, telling us it was a “medium” blend of Latin American coffees, perfect with chocolate.

“But, then,” Crystal explained, giving us both a big smile, “all coffees go well with chocolate; they’re kissing cousins. You’ll like the taste of Verona with this espresso brownie.”

She left us to enjoy our coffee and brownies. It was as though we were guests in her home. It was certainly a totally different experience than any I had been expecting. The Verona coffee with the espresso brownies was a delicious combination—Crystal was right.

Then Crystal brought us a Colombian coffee with a slice of pound cake.

“This is in the ‘mild’ category,” she said. “Can you taste the difference?”

“It sure seems lighter than Sumatra,” I said.

“Right, ‘lighter’ is a good word, Mike,” she said, as though she were a teacher congratulating an apt pupil. “Don’t worry, you’ll learn all about lots of different coffees here. By the way, you are going to be paid for the time you have been sitting here drinking coffee and having cake with Kester. Not bad for your first day on the job!”

Crystal left me with Kester. Though she had seemed so relaxed, I realized it might be just part of her management style. She was probably just putting a “new Partner”—me—at my ease. I realized Crystal was hard to read, and that it would take me a long time to really get to know her. She didn’t fit into any of my neat categories.

Ten years earlier, I couldn’t have imagined being so frightened and so eager and so desperate for this young woman’s approval.

And ten years ago, I couldn’t have imagined having espresso brownies, cake, and cups of coffee with someone like the physically intimidating Kester.

“Here’s how it works,” Kester said matter-of-factly. “We call it training by sharing. It just means that we do things together. I learn from you by helping you learn.” He picked up my cup in his and stood up. “Okay, now that you’ve had your coffee, I’ll show you how to make it.”

I followed him behind the bar.

Later, I came to know that Kester was the best “closer” at Starbucks. Closing the store late at night is one of the biggest management challenges because you have to be responsible for totaling up all the registers and making sure everything is perfectly stocked for the next day. Kester always made sure he got everything done on time and done right.

I didn’t know any of this on my first day on the job. I also did not know that one late night, months later, Kester would save my life.

3 One Word That Changed My Life

—a quote from Kevin Carroll, a Starbucks Guest, published on the side of a Decaf Venti Latte

MAY

I stood at the Bronxville station waiting for the 7:22 train to New York. I was not due to start my shift until 10:30 that morning—but I wanted to give myself more than enough time. The train from Bronxville to Grand Central took at least thirty minutes. The shuttle from Grand Central was another ten to twenty minutes to Times Square. From there I would jump on an express up to the West Ninety-sixth Station. I could then walk just a block or so to my store. I was anxious. I had not mastered the commuting routine and did not want to be late. I did not think I could afford any mistakes at my new job.

Waiting on the platform on that May morning, I had a chance to look around Bronxville. The little suburban village had changed a lot in the last few days as April showers heralded May flowers. Like in the movie The Wizard of Oz, the black-and-white winter had gone and the spring colors had arrived. There were now masses of bright red and white tulips everywhere—almost garish in their profusion. The forsythia was a burst of yellow. The trees had that first green tint that was like a soft mist against the brightening blue morning sky.

I sighed and then out of nowhere began to cry softly. The tears silently ran down my cheeks as I tried to suppress them. I did not want to draw attention to myself in that mass of energetic commuters. The men and women all seemed to be dressed in Brooks Brothers suits and were bubbling with a kind of self-congratulatory exuberance that I now found sickening.

I was jealous of them for their confidence about their lives.

I hated them for the ease with which they seemed to face their commute.

I knew I was relatively invisible to them. Dressed in my black pants, shirt, and Starbucks hat, I looked like what I was—a working guy. Just another of those people who showed up at odd times to join the commuter rush—but were heading for service jobs too menial for the Masters of the Universe to notice.

I tried to brush the tears away, but they would not stop. Maybe it was an allergy from all the pollen now filling the air? But I knew it was not.

There was something so incongruous and sad about my standing on that platform waiting for a commuter train in my uniform so many decades after I first arrived in this exclusive town. My father had decided, after my mother had several more children (it seemed to me that my father was anxious for another son, that I was a real disappointment to him, and that was why he kept trying) that we had to leave the city.

My father chose a huge Victorian mansion in Bronxville because it was close to the city and a good public school. But Bronxville was not a happy place for me.

Every single day when I walked to school, a bully named Tony Douglas would leap out from behind a bush, push me down, and twist my arm until I cried. It was humiliating to cry at eight or nine, but I could not—eventually—resist. I knew crying was the only way to get him to stop. He really hurt me. He scared me. It was like he might break my arm. In the winter he would push my face down into the snow and rub it until I begged him for mercy. I had to beg to get away from him. Then he would leap up and run away laughing. I would slowly rise, in real pain, trying to gather up my books.

Not that I could read. That was another reason that I was so unhappy in Bronxville. When I got to school, I was in for more daily humiliation. Try as I might, I could not learn to read. I really tried. All my classmates learned. It was terrible to be sitting there in the midst of my classmates and not see what they could see and not be able to speak out loud the words that they could so proudly speak. The words in the books the teachers gave me to read seemed to be created in some secret code that I could not break. The sentences jumped before my eyes. I tried to will myself to break the code, but could only guess what those black lines meant.

How horrible it felt to me to be alone in this public proof of my stupidity, my obvious inability and misery.

My failure was impossible to ignore.

Miss Markham was the principal in the elementary school. She was a terrifying figure. Dressed in a black suit, she would march down the halls issuing commands in a deep voice.

I was brought to her attention.

She called my parents to come in and speak to her.

My mother was embarrassed; my father was clearly angry. I had ruined his day.

“Why couldn’t she see us at some other time?” my father asked my mother. “It’s right in the middle of my morning!”

For some reason Miss Markham took my side. Somehow, she had decided, despite all the signs to the contrary, that I would turn out all right. She also had insisted on including me in the “parents” conference.

“I never talk about children behind their backs,” she explained.

Right in front of me, she told my parents, “Michael will read when he wants to. Stop badgering him.”

I was dumbfounded by her attack on my parents. For she was clearly very cross with them. I had always been told how wonderful my parents were. She seemed to feel that I should be protected from them in some way.

Her apparently irrational faith was eventually justified, although reading came to me not through any act of concentration or panicky desire, but just gently, easily, one summer in the country when I was ten.

Every summer we would leave Bronxville for a small country town in the mountains of Connecticut. Mother was much happier there. She had gone to Norfolk for summers when she was young, and there were still many friends from her youth who summered there. Her best friend from childhood had a house just a few fields away, and her son became my best friend. We would ride our bikes down the old dirt roads and go for swims in the little lake.

Mother would get me out of bed early in the morning so I could see the dew sparkling in the sun.

“Elves’ jewels,” she would say, hugging me with delight. “Is there anything more beautiful in the world than a summer morning in Norfolk?”

Sometimes she would get me out of my bed at night after I was asleep and take my hand and lead me out to look up at the moon.

“Isn’t it glorious?” she would say, a happy lilt in her voice.

But my happiest memory was sitting with Mother on a steamer rug while she read to me. Across the field I could see a group of birch trees. Their leaves would flutter in the soft breeze…. One moment they would be green, and then silver in the bright sun of a late summer afternoon.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.