Полная версия

History of the Soviet Union

Geoffrey Hosking

A History of

the Soviet Union

1917–1991

Final edition

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

A Fontana Press Original 1985

Revised edition published by Fontana Press 1990

This Final Edition published 1992

Copyright © Geoffrey Hosking 1985, 1990, 1992

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780006862871

Ebook Edition © JANUARY 2017 ISBN: 9780007545285

Version 2017–01–19

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

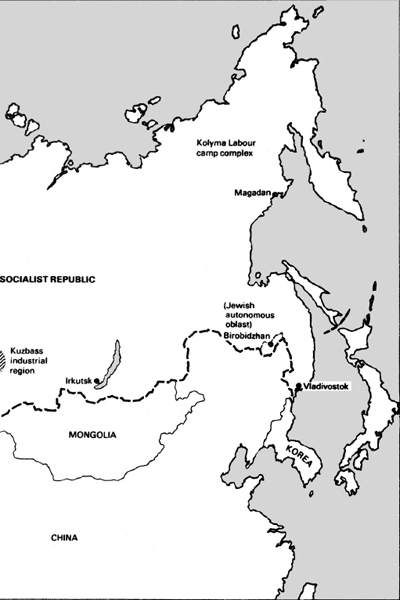

Maps:

The Soviet Union

The Soviet Union in the Second World War

The Soviet Union in Eastern Europe

Prefaces

1. Introduction

2. The October Revolution

3. War Communism

4. The Making of the Soviet Union

5. The New Economic Policy and Its Political Dilemmas

6. Revolution from Above

7. Stalin’s Terror

8. Stalinist Society

9. Religion and Nationality under the Soviet State

10. The Great Fatherland War

11. The Last Years of Stalin

12. Krushchev and De-Stalinization

13. Soviet Society under ‘Developed Socialism’

14. Religion, Nationality and Dissent

15. The Decline and Fall of the Soviet Union

Chronology

Statistical Tables

Bibliography

Index

Keep Reading

About the Publisher

A HISTORY OF THE SOVIET UNION

Geoffrey Hosking has been Professor of Russian History at the School of Slavonic Studies, University of London, since 1984. Born in Scotland in 1942, he studied Russian at Cambridge and European History at Oxford before gaining his doctorate in modern Russian history on the basis of archive work done in Moscow and Leningrad. He has taught at the universities of Essex, Wisconsin, Cambridge and Cologne, and has been a Senior Research Fellow at Columbia University in New York. Amongst his other books are The Russian Constitutional Experiment: Government and Duma, 1907–1914 (1973) and Beyond Socialist Realism: Soviet Fiction since ‘Ivan Denisovich’ (1980). In 1986, A History of the Soviet Union won the Los Angeles Times history book prize. In 1988, Professor Hosking was invited to give the annual Reith Lectures; he spoke on the subject of Change in Contemporary Soviet Society.

Maps

Adapted from Martin Gilbert, Russian History Atlas (1972)

Preface

Viewed from the West, the peoples of the Soviet Union tend to seem grey, anonymous and rather supine. When we see them on our television screens, marching in serried ranks past the mausoleum on Red Square, it is difficult to imagine them as more than appendages–or potential cannon fodder–for the stolid leaders whom they salute on the reviewing stand. This is, of course, partly the image the Soviet propaganda machine wishes to project. But is it not also partly the result of our way of studying the country? So many general works on the Soviet Union concentrate either on its leaders, or on its role in international affairs, as seen from the West.

There is plenty on the Soviet leaders in this book, too. No one could ignore them in so centralized and politicized a society. But I have also tried to penetrate a little more into their interaction with the various social strata, the religious and national groups, over which they rule. Fortunately, in the last ten to fifteen years, quite a large number of good monographs have been published in the West and (to a lesser extent, because of censorship) in the Soviet Union itself, which enable us to say more about the way of life of the working class, the peasantry, the professional strata, and even the ruling elite itself. In addition, many recent émigrés have, since leaving, given us candid accounts of their lives in their homeland, and these have afforded us a much more vivid insight into the way ordinary people think, act and react.

In order to focus on this material and give, as far as possible in brief compass, a rounded picture of Soviet society, I have deliberately said little or nothing about foreign policy or international affairs. There are already many excellent studies from which the reader can learn about the Soviet Union’s role in world affairs: to add to them is not the purpose of this book. I have, however, given some consideration to the Soviet Union’s relationship with the other socialist countries lying within its sphere of influence. As I argue in Chapter 11, developments in those countries have a claim to be considered almost as Soviet internal affairs; besides, East European efforts to discover their own distinctive ‘roads to socialism’ have brought out elements in the socialist tradition which have been obscured or overlaid in the Soviet Union itself. These elements may yet be of great importance, and therefore it is essential to give them due weight.

I have, moreover, again in the interests of concentration, consciously laid the strongest emphasis on the years of Stalin’s personal rule–roughly from the start of the first Five Year Plan in 1928 until his death in 1953–because this seems to me the most crucial period for understanding the Soviet Union today. It is also the one on which recently published works throw the greatest light.

In order to avoid cluttering the narrative and to allow a smoother flow of argument, I have dealt with some individual topics–such as literature, religion, education and law–not within each chapter, but in large sections confined to a few chapters. Thus, for example, the reader interested in the Russian Orthodox Church will find most of the material on it concentrated in Chapters 9 and 14. The index indicates these principal sections in bold type.

This history is the product of some fifteen years’ teaching on the Russian Studies programme at the University of Essex, and it reflects the often stated needs of my students on the post-1917 history course. I owe a considerable debt to them, especially to the inquisitive ones, who tried to encourage me to depart from vague generalization and tell them what life has really been like in a distant and important country they had never seen. I have also learnt a great deal over the years from my colleagues in the History Department and in the Russian and Soviet Studies Centre at Essex University. The marvellous Russian collection in the Essex University Library has provided me with most of the materials I needed, and I am particularly thankful to the collection’s custodian, Stuart Rees, for his unfailing attention to my wants.

I am most grateful to my colleagues who have read all or part of an earlier draft: the late Professor Leonard Schapiro, Peter Frank, Steve Smith, Bob Service and, the most tireless of my students, Philip Hills. At crucial stages of the writing, I have benefited from conversations with Mike Bowker, William Rosenberg and George Kolankiewicz. Where I have ignored their advice and gone my own way, I acknowledge full responsibility.

I am much beholden to the support and encouragement of my wife Anne, and my daughters Katherine and Janet. Without their endless patience and indulgence, this book would have been abandoned long ago, and then they might have seen more of me.

School of Slavonic Studies,

University of London,

July 1984

Preface to Second Edition

By a strange coincidence, the first edition of this book was published on the very day that Gorbachev became General Secretary of the Soviet Communist Party. That made for good publicity, but it meant that the text rapidly became overtaken by the remarkable events which began to take place under the new leadership. It is true that in the last pages of the old edition I remarked that change, when it came, would be rapid and far-reaching, and that the Soviet public would prove to be more ready for it than we were then accustomed to think. As a pointer to the future, that now seems to have been reasonably apt, but all the same, a mere four years into the new era, a generous extension of the last chapter seemed essential to give some idea of the momentous changes which have been occurring and to relate them to earlier Soviet history. I have taken this opportunity to correct a few errors earlier in the text, and thank those reviewers and readers who have pointed them out to me.

School of Slavonic & East European Studies,

University of London,

July 1989

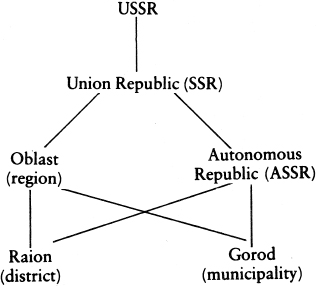

Administrative Divisions

Often in the text I refer to one or other of the main administrative divisions of the Soviet Union. These may be schematically laid out as follows:

1

Introduction

‘The philosophers have only explained the world; the point is to change it.’ This famous dictum of Marx invites us to judge his doctrine by its practical consequences, in other words by examining the kind of society which has resulted from its application. Yet, paradoxically, many Marxists themselves will deny the validity of such a judgement. They will dismiss the example of Soviet society as an unfortunate aberration, the outcome of a historical accident, by which the first socialist revolution took place in a country unsuited to socialism, in backward, autocratic Russia.

It is important, therefore, to begin by asking ourselves just why this happened. Was it indeed a historical accident? Or were there elements in Russia’s pre-revolutionary traditions which predisposed the country to accept the kind of rule which the followers of Marx were to impose?

It is true that Russia was, in some ways, backward and it was certainly autocratic. Economically speaking–in agriculture, commerce and industry–Russia had lagged behind Western Europe from the late Middle Ages onward, largely as a result of two centuries of relative isolation under Tatar rule. There is, however, no single track along which history advances, and this backwardness had positive as well as negative features. It made the mass of the people more adaptable, better able to survive in harsh circumstances. It may also have helped to preserve a more intimate sense of local community, in the peasants’ commune (mir) and the workmen’s cooperative (artel).

Politically, on the other hand, nineteenth-century Russia might be thought of as rather ‘advanced’, if by that we mean resembling twentieth-century Western European political systems. It was an increasingly centralized, bureaucratized and in many ways secular state; its hierarchy had strong meritocratic features; it devoted a considerable share of its resources to defence, and operated a system of universal male conscription; and it accepted an ever more interventionist role in the economy. Furthermore, the state’s opponents, the radicals and revolutionaries, pursued secular utopias with the same mixture of altruism, heroism and intense self-absorption which characterized, for example, the West German and Italian terrorists of the 1960s and 1970s. What Russia did not have, of course, was parliamentary democracy, though even that was developing, in embryonic form, from 1906.

As for autocracy, there were very good reasons why it should have proved the dominant political form in Russia, and why it should have been acceptable to most of the people. It is unnecessary to postulate an inborn ‘slave mentality’, as many Westerners are prone to do. First, there are Russia’s flat, open frontiers, which have been both her strength and her weakness. Her strength, because they gave Russia’s people the chance to spread eastwards, colonizing the whole of northern Asia and occupying in the end one-sixth of the earth’s surface. Her weakness, because they have rendered Russia ever vulnerable to attack, from the east, the south and, especially in recent centuries, from the west. For that reason all Russian governments have made the securing of their territory their chief priority, and have received the whole-hearted support of the population in so doing. National security has been, in fact, more than a priority–an obsession to which, when necessary, everything else has been sacrificed with the enthusiastic approval of the people. Any other people in such circumstances would react the same way. That is not to say that Russian governments have not abused the trust their subjects have placed in them: on the contrary they have found it possible to do so again and again. But the geographical and historical motives for accepting strong authority have nearly always prevailed.

Another reason for the popular identification with the autocrat is that, historically speaking, Russia’s formation as a self-conscious nation began unusually early. The Tatar occupation of the thirteenth century generated, by reaction, intense Russian national feeling, which centred on the Orthodox Church, as the one national institution which had survived the disaster. And because the church conducted its liturgy not in Latin but in a Slavonic tongue close to the vernacular, this national feeling had deep roots among the ordinary people. All this imparted to Russian national consciousness from early times a demotic quality, a defensiveness, and an earth-boundness which still have strong echoes today. Its religious basis was celebrated as soon as Russia was able, thanks to strong Muscovite rulers, to throw off the Tatar yoke. Moscow Grand Dukes proclaimed themselves Tsars (Caesars), claiming the heritage of Byzantium, which had fallen to the infidels in 1453: ‘Two Romes have fallen, the third Rome stands, and there shall be no fourth.’ Russia became Holy Russia, the one true Christian empire on earth.

In order to ensure that armies could be raised and the country defended, the tsars imposed a tight hierarchy of service on the whole population. Nobles were awarded land in the form of pomestya, or service estates, on condition that they performed civilian or military service, usually the latter. They also had to raise a unit of fighting men from among the peasants committed to their charge. In this way the old independent aristocrats, the boyars, were gradually displaced, while the peasants became enserfed, fixed to the land, bound to serve their lord, to pay taxes, and to provide recruits for the army. For nobles and peasants alike, their function and status in society was defined by state service. Society became almost an appendage to the state.

In the end, even the church was taken into service. The process began in the seventeenth century, when its head, Patriarch Nikon, tried to provide for the church’s imperial role by correcting liturgical mistakes which had crept into the prayer books over the centuries, and which he felt would shame the Russian Orthodox Church in its relations with other churches. He was also ambitious for the church to play a stronger role in the state. Although Tsar Alexei dismissed him as a dangerous rival, the reforms he had sponsored were ratified by a Church Council. These reforms aroused vehement opposition among both priests and laity, who felt that the integrity of the Russian faith was being violated by foreign importations. All the strength, exclusiveness and defensiveness of Russian national feeling was exhibited by the Old Believers, those who clung to the old liturgical practices, and were prepared to be imprisoned or exiled, or even commit mass suicide, rather than submit to the new and alien practices. The Old Belief survived right up to the revolution of 1917, and beyond, depriving the official church of many of its natural, indeed most fervent, supporters.

Perhaps the most significant aspect of this schism, whose importance for Russian history can scarcely be exaggerated, was that the church became dependent on the full coercive support of the state in implementing its reforms. The way was thus prepared for. Peter I, in the early eighteenth century, to abolish the Patriarchate, symbol of the independent standing of the church, and replace it with a so-called Holy Synod, essentially a department of state, headed moreover by a layman. Peter did this with the same aims as Henry VIII in England: to bring the church under firm state control, to discipline it and make it fitter to fulfil the tasks the state had in mind for it, such as education, social welfare and the pastoral care and supervision of the common people. His principal ecclesiastical theorist, Feofan Prokopovich, insisted that the state should have undivided and indisputable sovereignty on earth, including the right to interpret God’s law. Any less clear arrangement he deemed dangerous, since it might mislead ordinary, gullible people to entertain the ‘hope of obtaining help for their rebellions from the clergy’. This secular approach to church-state relations, and the obsession with civil disorder, was close to the thinking of many European Protestant thinkers at the time, notably Thomas Hobbes. Shades of the Leviathan hung over Russian society from then on.

Peter I also impugned Russian traditions in numerous other ways. He moved the capital from Moscow to a swampy outpost on the Baltic coast, simply because that sea gave direct access to the ports of Europe, in whose more ‘progressive’ ways Peter hoped for salvation. In the new city of St Petersburg, he required his nobility to adopt European fashions in everything from education to clothing. When some of his courtiers refused to shave their beards–honoured as a sign of manhood in Muscovite custom–Peter took the shears and did the job personally. Both the changes he promoted, and his uncouth manner of imposing them, aroused considerable opposition. Old Believers, indeed, regarded him as the Antichrist.

Catherine II completed the subordination of church to state by expropriating the church’s huge landholdings, which left the priesthood poor and dependent on their parishioners for subsistence. The clergy became in effect a subordinate estate, having neither the education nor the financial independence to cultivate a distinctive stand, even in spiritual matters. They were also a more or less closed order, since clergy sons usually had little choice but to take their education in a church seminary, and then to follow in father’s footsteps. The high culture and politics of the period were essentially secular: priests were regarded by most intellectuals as beings of inferior education and status, peddling superstition to pacify the plebs. It would be difficult to overstate the importance of this subordination of the church. It meant that Holy Russia, still haunted by visions of unique religious rectitude, was governed in a radically secular manner, outdoing most Protestant states, and was acquiring an almost aggressively secular culture.

Russian government in the nineteenth century is often described as ‘reactionary’, but this view is based on superficial comparisons with West European political systems. In fact, from the time of Peter I, Russian governments were radical and modernizing to an almost dangerous degree. They were so because they felt they faced a potential military threat from European nations which on the whole were technically better equipped. It was to face this challenge that Peter sacrificed so much to the creation of a strong army and navy, with a modern armaments industry to back them up, and overhauled the administration of the country, the tax system, education and even social mores. He regarded all the country’s resources–material, cultural and spiritual–as being at the service of the state for the good of society as a whole. His successors continued his work, but they faced both the advantages and disadvantages of weak social institutions. Advantages, in that no fractious nobility or urban patriciate possessed the independence to impede the monarch’s commands. Disadvantages, in that the existing aristocratic and urban institutions (the elites of town and country) were often not even strong enough to act as transmission belts for orders from above, as they did in other European countries; in their absence the government’s intentions often petered out ineffectually in the vast expanses of the landscape.

For that reason some Russian monarchs, notably Catherine II in the late eighteenth century, and Alexander II in the 1860s, actually tried to create or strengthen what Montesquieu would have called ‘intermediary bodies’, that is, self-governing associations of nobility and of townsmen, with a direct responsibility for local government. Others–Paul I, for example, and Nicholas I–regarded such associations as self-seeking and divisive, tried to curb them and to rule through monarchical agents, controlled from the centre. Much of the history of Imperial Russia’s government between Peter I and the revolution of 1917 is to be found in this swing to and fro between local autonomy and strict centralization, between support of local elites and distrust of them.

The radical intelligentsia of the nineteenth century were in some ways the unnatural offspring of this frustrating relationship. Most of the radicals came from the social strata from which the tsarist government recruited its central and local officials–the minor nobility, the clergy, army officers and professional men–and they typically went through the same education system as the country’s civil servants. They espoused many of the ideals of the modernizing wing of the bureaucracy: progress, equality, material welfare for all, the curbing of privilege. Frustrated, however, by the hierarchy and authoritarianism of the state service, and by the gross discrepancy between ideal and reality, they underwent a conversion, usually as early as their student days, and harnessed their vision to a revolutionary ideology.