Полная версия

Collins Mushroom Miscellany

{Laurie Campbell/NHPA}

People often express surprise that fungi have been placed in their own kingdom. This is usually because of an assumption that there are not very many different species of mushroom and toadstool, compared with the number of flowering plants.

Looking at the numbers from a British perspective, there are about 2,000 species of flowering plant growing in the wild. The recently published (2005) Checklist of the British & Irish Basidiomycota lists some 2,200 species of mushrooms and toadstools (agarics). In addition, the list includes 430 brackets and relatives, over 100 puffballs and relatives, around 100 club and coral fungi, about 20 hedgehog fungi and over 200 jelly fungi. All of the latter groups are included in books about ‘mushrooms’ together with some of the larger species of ascomycete (see here) such as the morels and truffles, taking the total number to well over 3,000 species of larger fungi. When all the lichens and smaller species of ascomycete are included along with the moulds and yeasts, together with plant parasites known as rusts and smuts we reach a figure in excess of 14,000 named species of fungi in Britain.

With the exception of garden escapees and deliberately introduced plants there have been very few newly discovered British species of flowering plant during the past 20 years. In contrast, species of larger fungi that have not previously been recorded in Britain are being discovered every year. Some of these may well be new to Britain (see here), but others represent native species that have previously escaped the attention of anyone capable of identifying them. As the number of both amateur and professional mycologists has grown so has our knowledge of the diversity of different fungal species in Britain.

Esher Common in Surrey, a 380 hectare site within easy reach of London (and the mushroom experts at Kew) has probably undergone more mycological recording than anywhere else in Britain, which means that it is possibly the best recorded area anywhere in the world. To date, over 3,200 species of fungi have been found there and new ones are being added to the list every year. The fact that there has been at least one professional mycologist based at Kew Gardens for the past 125 years, in conjunction with over a century of recording by members of the British Mycological Society, has left Britain with a wealth of fungal records.

Despite this, knowledge concerning the distribution of larger fungi in Britain is very patchy and some parts of the country are under-recorded; areas with many records may reflect the close proximity of a good mycologist rather than a region that is especially rich in fungi. Although some new records of the larger fungi reflect habitat and climate change (see pages ref1 and ref2), others are the result of keen observation and perseverance in attempts to identify species that are not featured in books about British fungi. That this can involve amateur mushroom hunters is explained in Chapter Six.

While new records of larger fungi are still relatively uncommon, the number of newly discovered species of microfungi is much higher. In many cases these prove to be not just new records for Britain, but species that are new to science. One example is a fungus that grows on the fallen leaves of woody plants with leathery leaves, including the strawberry tree (Arbutus unedo). During the time that I was writing this book I heard a programme on Radio 4 about this newly discovered species. It has very unusual spore-bearing structures, unlike any previously described. My study window overlooks the front garden, which is home to a 10-year-old strawberry tree. I am looking forward to making a close (microscopic) examination of the decaying leaves from under the plant; there is always something new to look out for in the fungus world.

One of the principal aims of naturalists has been the classification and accurate naming of species; only when this is done can we answer the question, ‘How many species are there?’ The Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus may have revolutionised the classification and naming of plants in the middle of the 18th century, but he never came to terms with the fungi. In 1751 he wrote:

The order of Fungi, a scandal to art, is still chaos with botanists not knowing what a species, what a variety.

In one of his publications he included the fungi under the name Chaos, and even in his magnum opus of plant classification (Species Plantarum) published in 1753, he included only 10 genera of fungi and a total of just 90 species, despite the earlier work of an Italian mycologist who had listed over 900 species. It was left to Christiaan Persoon to sort out the chaos of the fungi. The man who was to do for fungi what Linnaeus did for flowering plants was born in the Cape of Good Hope in the early 1760s, was sent as a teenager to school in Germany and finally settled in Paris. His publications included books on the lower plants and four important works on the classification of fungi. His system of fungal classification was largely based on the morphology of the fruiting bodies and most of the 100 genera that he created are still recognised today.

The next great taxonomic mycologist was born in the last decade of the 18th century and had a background that was remarkably similar to that of Linnaeus, who was born nearly 90 years earlier. Like Linnaeus, Elias Fries was born in southern Sweden and was the son of a clergyman. Both men went to the same school and ultimately both became Professor of Botany at the University of Uppsala. Fries recorded the event that was to start his interest in fungi. As a 12-year-old he was picking wild strawberries when he found a large specimen of a species of Hericium, a beautiful creamy-white fungus that looks like a cross between a coral and a mass of stalactites.

As with the method Linnaeus used to classify plants, many of the fungal classification schemes devised by Fries are now little used, but his knowledge of fungi enabled him to describe, name and study nearly 5,000 species, including many from outside his native country. Fries concentrated on the agarics (mushrooms and toadstools), where he was the first person to use spore colour to separate different groups, a feature still considered important by modern taxonomists. Fries died in 1878 and so was a contemporary of two of Britain’s great 19th century mycologists, the Reverend Berkeley and Mordecai Cooke (see here).

Because there was a long-held belief that fungi were the result of the devil’s work, the study of fungi was not approved by the Church until the 19th century, by which time knowledge about mammals, birds and flowering plants was already at an advanced stage. Watling has commented that as a result of this the scientific understanding of fungi lags 100 years behind that of many organisms.

The 20th century continued to produce eminent European and North American mycologists. Of the latter, one character was Curtis Lloyd who, before he died in 1926, became one of the leading experts in puffballs and their relatives. He once bought the stock of a failed shoe shop for the sake of the boxes to house his collection. He was not above playing a joke on his fellow mycologists and even named a fictitious puffball Lycoperdon anthropomorphus.

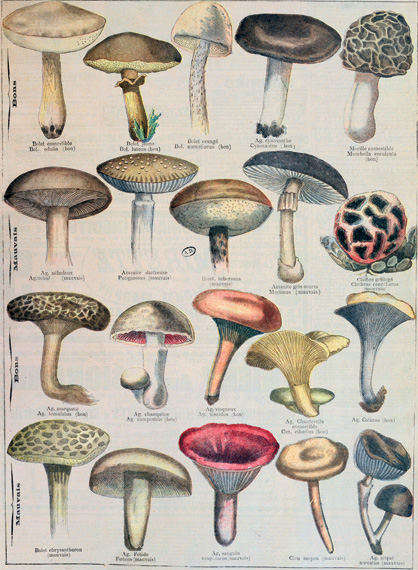

Good and Bad Mushrooms (c. 1900)

{Archives Charmet/BAL}

The work of European and American mycologists has resulted in a fairly good knowledge of at least the larger fungi in many northern temperate parts of the world. Despite this there is a paucity of information about fungi in tropical and subtropical regions, where the diversity of plant and animal species is at its greatest. It is for this reason that estimates of the total number of fungal species in the world remain guesswork. Writing in 1981, Rod Cooke introduced his book Fungi with:

There are over 50,000 known kinds of fungi, and it has been estimated that about 200,000 more await discovery.

A quarter of a century later the number of known, named species is in the region of 100,000, and the total has been estimated to be closer to 1.5 million different species. The figure of 1.5 million has been arrived at by observations, spanning a range of habitats, that the number of fungal species is, on average, six times greater than the number of flowering plant species. This ratio also works for Britain as a whole, as there are approximately 12,000 named species of fungus and some 2,000 species of flowering plant.

Some scientists believe that the global figure for the number of fungal species may be much higher, particularly as many insects, mosses and ferns appear to harbour unique, but largely unstudied, species of fungus. One estimate has put the worldwide fungal species count as closer to 9 million. Whatever the true figure there is plenty of work to be done: every year mycologists at Kew name about 1,500 new species, collected from all over the world. That we may have named as few as 1% of the world’s fungal species is indicative of just how little we know.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.