Полная версия

Cromwell’s Blessing

Copyright

HarperPress

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperPress in 2012

Copyright © Peter Ransley 2012

Peter Ransley asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007312405

Ebook Edition © September 2014 ISBN: 9780007463596

Version: 2014-10-10

Dedication

For Finlay

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

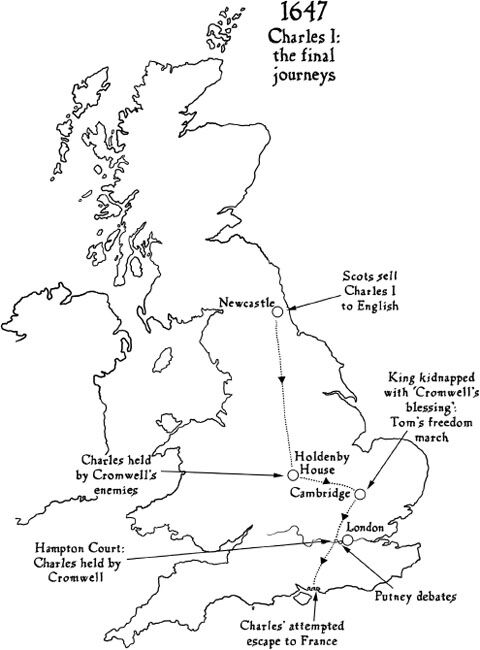

Map

Part One: A Silver Spoon

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Part Two: Cromwell’s Blessing

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Part Three: Without

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Part Four: The Signature

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Historical Note

Read an extract from THE KING’S LIST

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Peter Ransley

About the Publisher

1

I could not stop shivering. That February morning in 1647 was the coldest, bleakest morning of the whole winter, but it was going to be far colder, far bleaker for Trooper Scogman when I told him he was going to be hanged.

Most mornings I woke up and knew exactly who I was: Major Thomas Stonehouse, heir to the great estate of Highpoint near Oxford, if my grandfather, Lord Stonehouse, was to be believed. Now the Civil War was over, sometimes, in that first moment of waking, I woke up as Tom Neave, one-time bastard, usurper and scurrilous pamphleteer.

That morning was one of them.

I should have left it up to Sergeant Potter to tell Scogman, but he would have relished it: taunted Scogman, left him in suspense. At least I would tell him straight out.

My regiment was billeted at a farm near Dutton’s End, Essex, part of an estate seized by Parliament from a Royalist who had fled the country. The pail outside was solid ice. The dog opened one eye before curling back into a tight ball. Straw, frosted over in the yard, snapped under my boots like icicles. A crow seemed scarcely able to lift its wings as it drifted over the soldiers’ tents.

More soldiers in their red uniforms were snoring in the barns, where horses were also stabled. We were a cavalry unit, the justification for calling Cromwell’s New Model Army both new and a model for the future. Whereas the foot soldiers were pressed men, who would desert as soon as you turned your back, the cavalry were volunteers. They were the sons of yeomen or tradesmen, who brought to war the discipline of their Guilds. They joined not just for the better pay – and the horse which would carry their packs – but because they were God-fearing and believed in Parliament.

Except for Scogman.

I approached the wooden shed which was the camp’s makeshift prison. I half-hoped Scogman had escaped, but I could see the padlock, still intact, and the guard asleep, huddled in blankets.

Scogman on the loose would have been worse. The countryside would have been up in arms. Villagers resented us enough when we were fighting the war. Now it was over, and we were still here, they hated us.

Six months had passed since the Royalist defeat at the battle of Naseby. Yet the King was in the hands of the Scots. We were supposed to be on the same side – but the Scots would not leave England until they were paid and there were rumours they were doing a secret deal with the King. In spite of the stone in his bladder, his piles and his liver, Lord Stonehouse was in Newcastle, negotiating for the release of the King.

‘We could not govern with him,’ he wrote tersely to me. ‘But we cannot govern without him.’

The guard, Kenwick, was a stationer’s son from Holborn – I knew them all by their trades. I prodded him gently with my boot. ‘Still there, is he?’

Kenwick shot up, turning with a look of terror towards the shed, as if expecting to see the padlock broken, the door yawning open. He saluted, found the key and made up for being asleep on duty by bringing the butt of his musket down on a bundle of straw rising and falling in the corner. The bundle groaned but scarcely moved. Kenwick brought the butt down more viciously. The bundle swore at him and began to part. Somehow, I thought resentfully, even in these unpromising conditions, Scogman managed to build up a fug of heat not found anywhere else on camp.

I waved Kenwick away as, with a rattle of chains, Scogman stumbled to his feet. His hair was the colour of the dirty straw he emerged from, the broken nose on his cherub-like face giving him a look of injured innocence. Trade: farrier, although sometimes I thought all he knew about horses was how to steal them.

‘At ease, Scogman.’

He shuffled his leg irons. ‘If you remove these, sir, I will be able to obey your order. Major Stonehouse. Sir.’ He brought up his cuffed hands in a clumsy salute.

Kenwick bit back a smile. I stared at Scogman coldly.

He was about my age, twenty-two, but looked younger, thin as a rake, although he ate with a voracious appetite. Scoggy was the regiment’s scrounger. He stole for the hell of it, for the challenge. In normal life he would have been hanged long ago. But when a regiment lived off the land he became an asset.

It only took one person to point out a plump hen, and not only would chicken be on the menu that night, but a pot in which to cook it would mysteriously appear. There were many who looked the other way in the regiment, except for strict Presbyterians like Sergeant Potter and Colonel Greaves, but in war the odds had been on Scoggy’s side. In this uneasy peace his luck had run out. Scoggy had been caught stealing not just cheese, but a silver spoon. Not only that. He had stolen it from Sir Lewis Challoner, the local magistrate.

I chewed on an empty pipe, knocked it against my boot and cleared my throat. Scogman could read my reluctance and in his eyes was a look of hope. I cursed myself for coming. I should have sent Sergeant Potter. Scoggy would have known, however Potter taunted him, there was no hope. I struggled to find the words. In my mouth was the taste of the roast suckling pig Scoggy had somehow conjured up after Naseby. Even Cromwell had eaten it, praising the Lord for providing such fare to match a great victory. Cromwell believed in the virtue of his cavalry to the point of naivety, but when they sinned, he was merciless. I must follow my mentor’s lead.

‘You know the penalty for stealing silver, Scogman?’

‘Yes, sir. Permission to speak, sir.’

‘Go on,’ I said wearily.

‘Wife and children in London, sir. Starving.’

He knew I had a son. We had talked over many a camp fire about children we had never or rarely seen. ‘You should have waited for your wages like everyone else.’

‘We’re three months behind, sir. There’s talk we’re never going to be paid what we’re owed.’

It was true Parliament was dragging its feet over the money the troops were owed, and a host of other problems, like indemnity and injury benefits. Meanwhile soldiers scraped by on meagre savings, borrowed or stole.

‘That’s nonsense. Of course you’ll be paid. Eventually. You should tighten your belt like everyone else.’

Scogman glanced down at his belt, taut over the narrow waist of his red uniform. Again Kenwick repressed a smile. I took the spoon from my pocket. My breath fogged it over. It looked a miserable object to be hanged for. ‘Why the hell did you steal a silver spoon?’

He couldn’t resist it. ‘Because I never had one in my mouth, sir.’

Kenwick showed no sign of laughing, after looking at my expression.

‘You will go before the magistrate.’

Even then he didn’t believe me. ‘I’d rather be tried by you, sir.’

‘I’ll bet you would. Sir Lewis may be lenient. Lock him up, Kenwick.’

I turned away, but not before I caught Scogman’s cockiness, his bravado, shrivel like a pricked bladder. Outside, while the crows flapped lazily away, I tried to do what Cromwell did when he ordered a man’s death. He prayed for his soul; it was not his order, he told himself, but God’s will. Then he would unclasp his hands and go on to his next business. Rising over the thud of the door and the rattle of the padlock came Scogman’s voice.

‘Lenient? Sir Lewis Challoner, sir? He’s a hanging magistrate! Major Stonehouse!’

I put my hands together but could not find the words to form a prayer.

2

Sir Lewis was also the local MP. He was, Lord Stonehouse had warned me, one of the more amenable Presbyterian MPs and a man I must be careful to cultivate.

There were now two parties. The Presbyterians were conservative, strict in religion, and softer in the line they pursued with the King. The Independents, led by Cromwell, were tolerant to the various religious sects that had sprung up during the war, such as Baptists and Quakers. They wanted to make sure the absolute power of the King, who had plunged the country into five years of devastating war, was removed.

That, at least, was how I saw it. My burning ambition was to be one of the Independent MPs who reached that settlement. I was Cromwell’s adjutant when Lord Stonehouse suggested I was sent here to quell the unrest. He did not say so, but I was sure it was a test – handle the delicate relationship between soldiers and villagers and I would be on my way to Parliament. It was all the more important because the New Model Army was Cromwell’s power base. Discredit the army, and you discredited him.

Word about Scogman got round quickly. Troopers saluted me, but averted their eyes and muttered in corners. I retired to the farm kitchen where Daisy, the kitchen maid, brought me bread and cheese and small beer. Her eyes were red. She sniffed and wiped her nose with the corner of her apron. Scogman not only stole chickens, pigs and silver spoons; he stole hearts. She kept poking the fire, scrubbing an already scrubbed pot and sniffing, until she turned to me, blurting out the words.

‘It’s my fault, sir.’

‘Your fault, Daisy?’

‘He stole the silver spoon for me, sir.’

‘Why on earth would he do that?’

‘It’s, it’s … a sign of love, sir.’ She scrubbed the scrubbed pot and went as red as the fire. ‘Is it true, sir … you’re going to hang Scoggy?’

‘No, Daisy.’ Her eyes brightened. I gulped down the remaining beer. ‘He’s going before the magistrate.’

She burst into tears and fled.

Worst of all was Sergeant Potter who congratulated me for getting rid of that evil, thieving bastard. That would send a message to the other God-forsaken backsliders! The regiment was getting out of control and Dutton’s End was up in arms. Had I marked the minister’s sermon, echoing other sermons throughout Essex calling for a petition to Parliament to disband the army, which from being a blessing had become a curse, a leech, sucking the life-blood from village and country?

I winced when he said his only regret was that he could not tie the neckweed himself and retreated to the outhouse where I had my office. I wrote the letter to Sir Lewis, handing Scogman over to his jurisdiction and asking him for a leniency I knew he would not grant. I sent for Lieutenant Gage to deliver it. Instead I got Captain Will Ormonde.

Of all the delicate situations at Dutton’s End Will was the most sensitive. We had rioted together in the uprising for Parliament, the riots that had driven the King from London. We had fought in the first battles of the war together. When this regiment’s Colonel, Greaves, had fallen ill, Will had expected promotion. Instead, I had been sent to take temporary charge. He was right to think bitterly that it was because of Lord Stonehouse he had been passed over. But it was only partly that. He was too hot-headed and radical. Before I got here, he had made a bad situation worse.

Will was in his early twenties but, like all of us, looked older. He wore his hair long to cover an ear mutilated by a sabre slash.

‘You can’t send Scoggy to that bastard, Tom. We’ve all eaten his meat.’

‘This isn’t meat. It’s a felony.’

‘He’s denied it.’

‘Will, he was seen at the robbery! I searched his pack and found the spoon there. I’ve given him warning after warning.’

‘I know,’ he conceded. ‘But Scoggy.’

That was his best argument. But Scoggy. Scoggy was more than a scrounger. A thief. A womaniser. He was a joke at the end of a day of despair. The man who could always find a beer, whose flint was dry when everyone else’s was wet.

Will stared at the letter I had written, sealed and ready for Lieutenant Gage to deliver. ‘Try him here.’

‘Parliament wants felonies passed to the civil authority.’

‘Parliament.’ There was disappointment, frustration, impatience in his voice.

‘It’s what we fought for.’

His answer was to pull out a sheet of paper. ‘Have you seen this?’

I knew what it was before he handed it to me. There was a rebellion in Ireland and the army was trying to raise volunteers. The paper contained the names of the men in the regiment. Only a few had ticks by them. They were rootless men like Bennet, a gunsmith, who had developed a taste for war and was the regiment’s crack marksman. The last thing the vast majority wanted was to go to Ireland. They wanted, above everything else, what I wanted – to go home.

‘The men believe they won’t be paid unless they agree to go to Ireland.’

‘That’s nonsense.’

‘That’s what Potter’s saying.’

‘I’ll speak to him.’ I picked up the letter.

‘Tom. If you send that letter to Sir Lewis the soldiers will riot.’

My mouth was suddenly dry. I got up, opened the door and shouted for Lieutenant Gage. I waited until I was sure of controlling my voice. ‘There is to be no riot, Will. You are to keep order.’

His fists were clenched, his face a dull red. I could see Lieutenant Gage approaching. Will brought his hand up in a salute and barked savagely: ‘Very good, sir.’ He almost cannoned into Gage on his way out. I handed Gage the letter and gave him instructions for delivery.

It was a few minutes before I could stop shaking.

There was a lane with high hedgerows not far from the shed where Scogman was kept. It twisted away from the camp towards Dutton’s End and I hoped that, if the bailiff took Scogman that route, any disturbance could be kept to a minimum. The last thing I expected was for Sir Lewis Challoner to come for his prey himself.

He had been a Royalist at the beginning of the war but when he had seen which way the wind was blowing had changed sides, bringing a vital artillery train to Parliament. He rode into the farmyard followed by his bailiff Stalker. He looked as if he had lunched well, spots of grease gleaming on his ample chins as he smiled affably down at me from his horse.

‘Well, well, Major. We are returned to the rule of law, are we?’

‘We never left it, Sir Lewis,’ I said, returning his smile.

There was a cheer from somewhere nearby, and the smile went from Sir Lewis’s face. Soldiers had appeared from the barn and the stables. Daisy was at the kitchen window, dabbing her face with her apron. Bennet, the marksman, was cleaning his musket. The dog that followed him on his poaching expeditions was at his heels.

I could smell the wine on Sir Lewis’s breath as I went close to him. ‘Better do this as quietly and quickly as possible.’

He gave me a fat, innocent, smile. ‘You can control your men, can’t you, Major?’

‘You are provoking them, Sir Lewis,’ I said coldly. ‘I will not have it. If you want him, take him.’

He glared down at me. ‘Very well. The felon, Stalker.’

Stalker did not smile. He was a devout Puritan and gave the soldiers a gloomy but satisfied look, as if the world, which had been upside down, had righted itself again and he was back in control. He nodded to several of them, as if to say – I know you. You stole a ham. And you, you fornicator. She’s with child. Don’t worry. I have you all on my list. Some of the men slipped away under his gaze. Others muttered angrily. Only Bennet returned his gaze with interest, and patted the growling dog gently.

I got my horse and led the two of them across the fields. Sir Lewis still seemed eager to pursue an argument. He jerked his thumb back at the soldiers. ‘Some of those fellows, I believe, think the final authority rests not with the King, nor the Commons, but the people.’

I shook my head. ‘They might in a London alehouse. Not here.’

His pale eyes narrowed. ‘Is that so?’

‘Most are not interested in politics, Sir Lewis. All they want is to be paid what they’re owed, go home to their families, work and no longer be a burden to the countryside.’

‘They are pagans,’ Stalker said. ‘They declare themselves preachers. Spread false doctrine.’

‘They only pray here, Mr Stalker, because you will not allow them in your church.’

‘Because they are rabble, sir.’

‘They preach because they have no minister available. Is it not better that they try to reach God, than not try at all?’

Sir Lewis pursed his lips. ‘Dangerous, sir, dangerous.’ But he was mollified by the sight of Scogman in chains being bundled into a cart by Sergeant Potter. Stalker rode off towards them, and Sir Lewis thawed even further, to the extent he said he could see why Lord Stonehouse put such an extraordinary amount of trust in so young a man. He gave me a prodigious wink and began to rhapsodise about the beauty of the countryside around us. It was neglected, but the soil was rich and it was well watered. He gave me another wink, a slap on the back and said perhaps we could meet again to talk about country affairs. I was somewhat bemused by this abrupt change of heart, but put it down to the wine at lunch and – perhaps a little – to my diplomacy.

‘My regards to Lord Stonehouse,’ he said, and made as if to leave.

I turned away, expecting Sir Lewis and Stalker to ride off immediately, escorting the cart and its prisoner down the lane to avoid the soldiers. But I heard Scogman give a yell of pain.

I ran back to see the cart had come to a stop at the beginning of the lane. Scogman was being manhandled from it by Stalker and Sergeant Potter. They were threading a rope through his chains with the intention of tying it to Stalker’s saddle. I hurried back to them.

‘Sir Lewis, for pity’s sake take him in the cart! You will rouse my soldiers!’

He put on a puzzled look, belied by his quivering jowls. ‘The New Model Army? It is a model of discipline, Major, is it not?’

Scogman pulled away, tripping and falling. His britches were torn and his legs bleeding where the chains had cut into them.

‘Release him. Take him in the cart, or you do not take him at all.’ I struggled to keep my voice even.

Stalker hesitated. Sir Lewis lifted his head. I could see why they called him a hanging magistrate as he gave me a look of unflinching hostility. But he kept his voice friendly, even jovial, taking out the letter I had sent him.

‘This is your signature, sir? Your seal, is it not? You have released him to me and I will have him as I will. Good day to you, sir. Get on with it, Stalker! What are you waiting for, man?’

Stalker yanked Scogman towards his horse and tied him to his saddle. I stood impotently. What a stupid, naive fool I was to think a man like Challoner would ever be in a mood for compromise. He wanted to drag his prisoner through the town to demonstrate his power. Stones, rotting vegetables and shit would be hurled at him. He would be lucky to enter prison alive.

Diplomacy? Far from helping to heal the wounds between town and soldiers, releasing Scogman would inflame them.

At least if God had made me eternally hopeful – or hopelessly naive – he had given me the quick wit to get out of the mire I found myself in. Or perhaps, as some had held, ever since I was born, it was the Devil.

And mire it was. Crows rose and flapped as soldiers, aroused by Scogman’s screaming, streamed from the farm. Will was keeping them half-heartedly under control, but I saw the barrel of a musket poking through the hedge. Stalker was riding slowly, Scogman stumbling after, almost under the hooves of Challoner’s following horse. As they saw the soldiers, Stalker urged his horse into a trot. Scogman stumbled and fell. He made no sound as he was dragged from the ditch into the lane and back again. Perhaps he would not cry out in front of his fellow soldiers. More likely he was barely conscious.

I pushed through the hedge but could not see the musketeer. It must be Bennet. If it was, Sir Lewis was as good as dead. We would no longer just have a problem of unrest but a major crisis that the Presbyterian majority in Parliament would seize on against Cromwell. I heard the click of the dog lock, releasing the musket’s trigger.

‘Wait!’ I shouted to Sir Lewis. ‘You have forgot the evidence!’

I pulled the spoon from my pocket. The ridiculous-looking spoon, slightly bent. A man’s life. Sir Lewis, a stickler for correctness in his court, checked his horse.

‘Get down from your horse unless you want to be shot,’ I said.

‘Go to hell.’

‘Get down, man, or I cannot guarantee your life!’