Полная версия

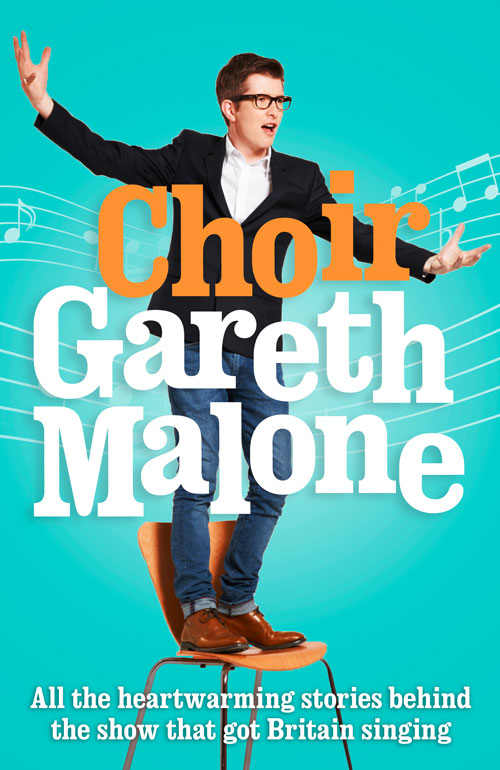

Choir: Gareth Malone

Also by Gareth Malone:

Music for the People

Contents

Just as the Sun Was Rising

If They Only Learn

I’ll Sing You a Song

When You’re Weary

How Foolish, Foolish Must You Be

Those Summer Days

The Night Has Come

Stand Up and Face the World

Really Care for Music

A Better Place to Play

Don’t It Feel Good?

Swear to Art

Someone Has to Believe

Probably Break Down and Cry

Keep Holding On

What Would Life Be?

Light up the Darkness

Home Again

Keep on Turning

Singing with a Swing

Coda: Make This Moment Last for Ever

Picture Section

Acknowledgements

Copyright Page

About the Publisher

For my grandmother Patricia – wherever you are

Just as the Sun Was Rising

January 2012. Heathrow Airport

Ping. It’s my phone. My mother is texting: ‘Get a copy of the Mail’. I’m about to board a flight to America to shoot a pilot for USA Network, which is strange enough, really. But what I read in a free copy of the Daily Mail while I’m waiting by the gate at Terminal 5 makes me aware of just how far I have come since my days selling ice cream on Bournemouth beach.

It’s now the New Year. The Military Wives have their victory – their single was Christmas Number One – and I’m busy jotting down ideas for an album on the back of my boarding pass. The whole extraordinary news furore that surrounded the release of ‘Wherever You Are’ has gone as cold as the weather outside and yet out of the blue one man breathes life back into the story.

In black and white, one of the most famous men in the world is quoted describing me (a tweedy choirmaster with a penchant for the music of Schubert and a love of country rambles) as follows: ‘He is like a stealth missile, he has sort of crept up on everyone. He would be good for us. I wasn’t furious about the Army Wives single beating us, I had two copies of it on pre-order.’ This is Simon Cowell speaking, no less, and I realise that my life has been irrevocably changed.

••••

Mr Cowell was not the first Simon to change my life.

In November 2005 I had a party for my thirtieth birthday. Having moved to London four years earlier – like everyone else, trying to make it in the big city – I had got together with Becky, who is now my wife, and it was a chance for us both to celebrate with all of our friends.

I felt good that night: not only did I actually have the £200 I needed to put behind the bar (a revolutionary moment after living a student’s life for two years), but when people asked me, ‘What are you doing next?’ I was able to say, ‘Oh, I’m making a series for BBC Two.’ It was an exhilarating time. In fact, the very first day of filming on the first series of The Choir was on my actual birthday: 9 November 2005. Now that’s how to turn thirty.

A few months earlier, I had just finished a massive London Symphony Orchestra project assisting American conductor Marin Alsop with the chorus on a project she was doing with the London Symphony Orchestra. This job had been a significant step-up for me as only weeks before I’d finished studying. Sat there in our slightly shabby West Hampstead box-cum-flat on my first morning off, I dithered over my next move while drinking a third cup of viciously strong coffee. I was exhausted, so I’d decided to relax, take the Monday really easy and have a lazy duvet day where I could sit and watch This Morning and not think about classical music at all.

But first I elected to have a long shower. Returning to my desk an hour later I found a message on my mobile from Simon Wales, a colleague of mine at LSO St Luke’s, the London Symphony Orchestra’s education centre.

The message was short and to the point. ‘We’ve had a call from someone from a TV company called Twenty Twenty. Would you be interested in being on a television programme?’ Forget the duvet day; I was intrigued and spurred into action.

The first thing I did was go to the Twenty Twenty website and check out the programmes that they had already produced. What caught my eye was that they had made Brat Camp. A couple of years earlier I had been quite ill one Christmas so I had been lying in bed watching television when the ‘Where Are They Now?’ update version of the show came on. The one-hour special revisited the whole journey and interviewed the kids who had participated in it (and their parents), allowing them to reflect on the impact the experience had made on their lives. I don’t mind admitting that it reduced me to floods of tears (a running theme in this book).

Years later I worked with the directors of that original series of Brat Camp and discovered that they had filmed the programme the hard way: that they’d lived in the Arizona desert and stayed with those kids for months and months to capture the amazing transformation in their lives.

As a rule I didn’t take anybody to the desert for therapy sessions, but I had been working in music education, which I’d found to be powerfully life-changing for many people. I imagined that something with a similar structure to Brat Camp could be done with music education. This was how I approached the project, thinking I could do the job I had been doing all over London to bring music into different schools and communities. I’ve always been zealous in wanting to encourage others to make music.

Music is part of my life: I have always sung. I remember my mother singing proper lullabies to me at bedtime. The sound of her voice was a very soothing presence when I was a young child. She would often sing an English folk song called ‘Early One Morning’, or ‘I Knew an Old Woman Who Swallowed a Fly’; simple songs for us adults but so absorbing when you are a child. I would join in on songs like ‘Incy Wincy Spider’, and become very involved in the story, visualising the spider clambering up the drainpipe. It’s lovely to sing these songs to my own daughter, rather like passing on the baton.

Even now whenever I hear the music and the words: ‘Early one morning, just as the sun was rising, I heard a young maid sing in the valley below’, I can see a house, a house that isn’t actually mentioned in the lyric, and a garden I invented for the maid to be singing in. Songs, and music generally, have always been very visual for me. I find music massively stimulating: I am sure that if you took a scan of my brain when I am conducting, singing or playing there would be a large amount of blood flowing towards my visual cortex. This is why I hate pubs and restaurants with background music. I can’t type, talk or concentrate when there is music on because I become absorbed in the sound.

Nowadays I start to see the way that a person is breathing or a violinist is bowing, but as a child it was much more about images and feelings. So those early songs were very powerful influences on me. I think that folk songs form the basis of your knowledge of harmony and your sense of what singing is for; ultimately, for me, it’s about communicating emotion

There was also one very particular moment when I was six or seven. I heard a Christmas carol which I remembered from the year before, and I felt a warm glow of recognition I had not experienced before. With hindsight I can see how powerful that was.

This was the beginning of an on-going connection with music, from stress-inducing competitions and piano exams to the excitement of duet lessons with a fellow pupil called Helen (with whom I was deeply in love when I was nine).

At ten years old I had my first taste of professional music-making. My school music teacher, David Naylor, came into the school orchestra rehearsal full of excitement to tell us that Andrew Lloyd Webber was seeking children to be part of the touring production of Evita. I was determined to get into the show. Andrew Lloyd Webber was sending someone to our school to run the auditions.

Michael Stuckey was the man he sent to find some stage-ready kids. Michael was to have the biggest influence on my life of anyone I ever met. He dazzled me with a combination of keyboard mastery and an easy manner with young people. He did not patronise me; he expected the very best. I met him for all of 20 minutes but they were 20 minutes I have never forgotten. I got into the choir and was sent a cassette with Michael’s voice teaching me the part. I had it on loop for a month. And I can still sing every note: ‘Please gentle Eva, will you bless a little child? For I love you …’. I fell in love with the stage during 16 wonderful performances of what I consider to be a very fine musical. Should the call come, I’m ready to play any of the parts. From memory. (Just in case you’re reading this, Andrew.)

Years passed, and when I came to work with young people I realised that I wanted to do it just like Michael Stuckey. I wanted to change people’s lives in the same way he had changed mine. I sought him out in 1999 through a new and exciting website called Google, and was sorry to hear that he had died unexpectedly years before. No doubt he’s whipped the celestial children’s choir into shape by now.

After that pivotal experience I began performing whenever and wherever possible. If there was a musical opportunity I was there: singing Christmas carol concerts, playing in the orchestra, learning percussion, piano lessons, doing music theory. At home I made up songs based around what was happening in my life. I wrote my first publicly performed piece of music (which, now that I think of it, was heavily derivative of the ITV Miss Marple music) for a school play in the first year of secondary school.

In my teens I started several rock/pop combos, the first of which was called Silence Is Purple. A later band was Little Nicola; we played a few gigs around the Bournemouth area in which I screeched my way with far too much vocal effort through some self-penned songs influenced by the Beatles, Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd – all very retro. Choirs. Orchestras. Jazz bands. It didn’t matter what the music was, I wanted to be involved.

All of this experience gave me a conviction that I could use music as a tool for self-discovery and that I could get any young person interested, given the right chance. A TV programme could be just that opportunity.

I arranged to meet up with Ana DeMoraes, now the head of development at Twenty Twenty, but then a more lowly member of the development department. It was Ana who had had the original idea to do something with choirs. Ana is a fascinating and unusual product of Brazilian and Japanese parentage, but since she has lived in the UK for over ten years she is also a passionate Anglophile. She is quiet and thoughtful, with an impeccable sense of what is fashionable in footwear. She’s also the most creative person I’ve ever met.

I later found out how Ana had tracked me down. At that time if you Googled the words ‘community choir’, mine was the first name to come up, because there was a brief CV and a photo of me on the London Symphony Orchestra’s website and the LSO had a high Google rating. Ana had looked at that and thought, ‘Oh, he might be half-presentable.’ There was a short clip of me singing a song with some kids and talking about what I was doing with the community choir, so Ana realised that I could string a couple of sentences together. Simultaneously she had contacted the LSO and asked them for some recommendations, and they’d said, ‘Oh yes, we’ve got the perfect person, Gareth Malone,’ so – thank you, LSO – they had put her straight on to me.

Ana’s voice is chirpy and she delivers her body blows in a silk glove. Her first audacious idea sounded almost impossible: ‘Could you go into a community and get it singing? In about nine weeks?’ ‘I could,’ I said, ‘but, to be honest, to make it a real and lasting project, you would need an enormous amount of time because it is very difficult to get a whole community onside.’

I had first-hand experience of this because I had been doing precisely that for the London Symphony Orchestra, working with local people just north of the Barbican. It is a very mixed area, with a strong Turkish enclave and a white working-class community, but there are also plenty of affluent people who live in the Barbican flats.

For a couple of years I had been trying to create a community choir by bringing all the different groups in the neighbourhood together: there was a little old lady who lived over the road from the church, one guy from down at the Barbican Centre and some kids from the local school. At that stage I had about 35 singers in the choir, but I was finding it really hard to get a sense of the choir as representing that whole community. Ana DeMoraes was suggesting repeating the experience in a matter of weeks. It was impossible.

I hastily warned Ana off that particular idea for the time being (although it would re-emerge three years later as Unsung Town), and suggested that we should try to create a choir in a school instead. I had also done a lot of work in schools and knew that the experience would be much more contained and controllable. It would give me the opportunity to work with a small group every single week, which is far more manageable.

Ana was intrigued and came down to one of the children’s choir rehearsals at St Luke’s, a beautiful Hawksmoor church where the LSO has been based since 2003. She says that the first thing she thought when she met me was, ‘He looks like one of the kids!’ But although in her eyes I looked so young: ‘The minute the rehearsal started, you were in control. I could tell the kids absolutely adored you. They wanted to please you. It reminded me of what I was like with my favourite teachers at school. And that had to be a good thing.’ She also thought that the warm-up exercises I started the rehearsal with ‘would make good telly’.

Apparently happy with what she had seen, Ana went away to do some more work on the concept. At that point the idea for the series was one of a social experiment. What would happen if we sent a genteel choirmaster into the lions’ den of a secondary school? Would he be ripped apart? Would it be gladiatorial? Would there be blood? I’m sure that someone at the BBC relished the prospect of a few chunks being taken out of me. Ana certainly saw some potential. ‘It seemed like the perfect combination: a posh, baby-faced choirmaster who nobody would think could win a bunch of rough kids over, with the passion and the skills to actually do it.’

So it was that, armed with a little Sony PD150 camera, a girl called Dee from Twenty Twenty who knew how to focus the thing came over to St Luke’s and did some filming of a rehearsal of my children’s choir. I gave it my all. Things went quiet again for a while. I had an agonising wait for any news about the series over that summer. Even though I was thrilled by the prospect, I didn’t want to alert too many people by telling them that I had been approached to be in the series, just in case it all came to nothing.

Life went on. I graduated from my post-graduate course in vocal studies at the Royal Academy of Music in June. Afterwards, at lunch with my parents in Getti’s Italian restaurant on Marylebone High Street, with me wearing all my finery and clutching my certificate from the Academy, I told them: ‘Oh, I’ve had a phone call about this possible television project, but it probably won’t amount to anything because I don’t think they’ve got a broadcaster involved. It is all very early days.’

To my parents it didn’t seem that improbable that the TV job might happen. They had become used to the idea of me working, not just for the LSO but also with English National Opera, Glyndebourne and the Royal Opera House on various education projects. However, I had begun other projects that had then fallen through, so in a very British way we were all quite reserved about the idea. But secretly I was really bloody excited.

It was important to me that my parents knew, because they had always been supportive of my musical ventures. My mother was, and is, a very good singer, who had studied as a child. She has a very pretty soprano voice, and loves opera. In fact, she had first met my father at the Gilbert & Sullivan Society in Tooting.

My father is also very musical, with wide-ranging tastes. His is a completely amateur enthusiasm, but he knows a huge amount about music, has an encyclopaedic memory for the Great American Songbook or anything twentieth-century, and rock and pop music up to circa 1972.

My maternal grandmother came from Mountain Ash in the valleys of South Wales, hence me being called Gareth. My grandfather was part of a theatrical family full of musical comedians, actors and actresses, so there was a huge amount of performance on my mother’s side of the family. I definitely think the humour and the clowning I often resort to comes directly from this – there is music and performance in my veins.

Over that summer of 2005 nothing much happened. I think it was heading towards the end of September when I got a call from Twenty Twenty, who had been busy pulling the series pitch together. At the end of an insane afternoon’s session for English National Opera, in a children’s centre working with about fifty toddlers, I was just leaving when my phone rang. It was Ana. She very simply said, ‘Yeah, we’ve got it, it’s been commissioned.’ I asked, ‘What does that mean?’ ‘It means you are making a television programme.’

Click. It was one of those life-defining moments where I thought, ‘This could change absolutely everything but then again it could change absolutely nothing.’ At that stage I had the feeling that the series might just get put on at 11.30pm and ten of my parents’ friends would watch it. I worried that it would be like so many TV programmes: utterly forgettable.

But I did consider what might happen if people liked the series. One night in our flat in West Hampstead I had a seminal conversation with Becky. It was getting late and as we got up from the sofa to go to bed, I said, ‘If we say yes to this series, it could completely change our lives. We have got to consider that. What if it goes to five or six series?’ That seemed like a total pipe dream at the time, but when you are signing up for something like this, you just don’t know. It’s like being at the top of a rollercoaster waiting for it to begin – sickening but thrilling.

My gut told me that this could be a good thing, that it would use all my skills to good effect. That gave me confidence about it. But I didn’t want to dither about whether I was going to take the plunge or not. That evening Becky and I both agreed, ‘Yep, we’re prepared. Let’s do this.’ To be honest we had no idea what we were getting into. We were two students. What did we know?

What I did know was that I enjoyed talking, and that was going to come in handy if I was featuring in a television programme. I am an only child so I have never wanted for attention. As a boy I had had loads of adult company. I was always spoken to as an adult, and talked, a lot, at a very early age. I always say I could talk for England.

One way and another I was confident that I could perform on television, but I did not realise the size of the challenge that Ana had dreamt up for me: ‘Do you think you could take a group of children who’ve never sung before and get them ready for the World Choir Games in China?’ ‘I don’t know.’ I sucked in some air. ‘I’ll give it a try.’

The prospect of taking a school choir to the World Choir Games in China the following summer sounded like a good focus for the whole adventure. How naïve I was. I had no idea of the difficulty involved. But for time being I put fear and dread aside, sipped the first of too many pints of London Pride and got on with my thirtieth birthday party.

If They Only Learn

My first taste of this new reality was walking into Northolt High School. Northolt had been chosen for the first series of The Choir because it was in an area of ‘relative deprivation’ as the headmaster put it: that was the phrase everyone bandied about. The TV company weren’t going to send me to Eton after all – they wanted a place that screamed, ‘There is no choir here.’ That suited me fine.

Northolt wasn’t a place I knew much about, other than its location off the A40 heading west out of London and that it had a tube station somewhere along the far reaches of the Central Line. I discovered as I arrived in Northolt that it had a nice little duck pond in an almost villagey centre. And there was also this huge and forbidding school.

When I saw the buildings they immediately reminded me of the school I had been to in Bournemouth. ‘Oh, it’s one of those schools,’ I said, on camera. I was thinking about the period of architecture, but that brief remark got me into a bit of trouble.

What I’d really meant but failed to get across was, ‘It’s one of those schools from that particular era of architecture, built in a hurry just after the war,’ exactly like some of my school’s prefab buildings. What rather a lot of people imagined I meant was, ‘Oh, it’s one of those schools,’ as if I’d been educated up the road in Harrow on the Hill. Quite a few people got really upset, and I had several letters of complaint (another running theme in this book). In fact, when the programme went out, I had a text from my cousin Keith immediately after that comment was aired saying, ‘You’ve just lost a million viewers.’ A little too late I realised that everything I said might be taken out of context. There was a lot for me to learn.

Northolt had 1,300 pupils and, like all large schools, there was constant activity and noise, with kids and staff swirling around on a typical morning. Spotting me arriving, one smart alec shouted, ‘It’s Harry Potter!’ out of the window when he should have been concentrating on maths. This led to me having the nickname among the production staff of ‘Gary Potter’. Thanks very much to that young gentleman.

I suspected the BBC thought I might not survive but that it would make jolly good telly. However, I felt fairly robust going in there and not unduly daunted. I’d spent years working in places like Hackney, Lambeth and Tower Hamlets in some pretty hot situations. I knew how to handle myself – oh yes – or I thought I did. On the day I’d started with the London Symphony Orchestra in 2001 I had found myself in a classroom full of 30 decidedly sweaty teenage boys in Hackney, left alone in charge of them with just a double bass player for moral support, as the teacher seemed to have disappeared. Now that definitely was intimidating. Surely Northolt would be a walk in the park?

What I didn’t feel all right about was being filmed; that was much more stomach-churning. Shortly before filming I’d sat down with the director of the series, Ludo Graham, in the Black Lion pub in Kilburn for a ‘getting to know you’ pint. Ludo, who is married to Kate Humble from Springwatch, was very experienced in this kind of television. Previously he had made Paddington Green, a documentary series in which he had followed characters from a small corner of London for a year or so. Over some London Pride and before I had fully signed up to the project, Ludo attempted to reassure me that making a TV programme would not finish my career if I trusted him.