Полная версия

Beyond Fear

The memory of such fear can stay with us for the rest of our lives, leaving us unable to enter any place which will remind us of our fear, or returning in dreams of terror when we find ourselves re-enacting, helplessly, the scenes where we once successfully escaped destruction. Some people, to give themselves freedom to go and do what they wish, put themselves through the painful process of therapy, in the hope that relearning a skill or talking about the events will remove the fear, and with that the shame of being afraid. Most people, however, adapt their lives to avoid certain situations and activities, by never entering an enclosed space or flying again, or they fog their sleeping brains with drugs to blot out dreams, or become what is known as ‘a light sleeper’, someone who is often awake while others sleep. They invent all sorts of excuses for not doing certain things - proneness to illness, or allergies, logical reasons for following one course of action rather than another - all to hide the fact that they are afraid. They must do this because they know, correctly, that to be afraid is to be scorned.

The fear we feel when faced with an external danger - fire or flood or a terrorist bomb - is bad enough, but what is far, far worse is the fear we feel when the danger is inside us. When the danger is outside us we know that at least some people will understand how we feel, but when the danger is inside us, when we live our lives in a sweat of anxiety, shame and guilt, we find ourselves in the greater peril that if we tell other people about our fear they will think that we are weak, or, worse, mad. So we take drugs to drown our fear and maintain the conspiracy of silence.

Edith was a very good woman who had devoted her life to others. She often acted as chauffeur for one of my clients, and while this client was talking to me Edith would visit some of the elderly patients in the hospital. One day she phoned me and asked whether, when she came the next day, she could have a quick word with me. I agreed, and so the next day she came into my room, apologizing for taking up my time and sitting nervously on the edge of her chair. What she wanted to know was whether she was going mad. The evidence that she might be was that she would often wake at 2 a.m. and lie worrying. The fear that pervaded her being manifested itself as the fear that no one would look after her when she was old. What if she became senile and incontinent, like the old women she visited on the psychiatric ward? She had done enough nursing to know that I could not truthfully say that her old age would not bring indignities and inadequacies, but there is one truth I could tell her.

Waking in the early hours of the morning in a sweat of terror is an extremely common experience. All across the country people are experiencing that terrible loneliness of being. They have woken suddenly to the greatest uncertainty a human being can know. There is no shape or structure to hold them. They are falling, dissolving; totally, paralysingly helpless without hope of recovery or of rescue. Sickening, powerful forces clutch at their hearts and stomachs. They gasp for breath as wave after wave of terror sweeps over them.

We all knew such terror when, as small children, we found ourselves in a situation which filled us with pain and helpless rage. We screamed in fear and in the hope that our good parents would rescue and comfort us. Now grown up, we know the extent of our loneliness and helplessness. Some of us wake, like Edith, completely alone. Some of us have another form sharing our bed, but it is effectively insensate, a log refusing to acknowledge our misery. Others of us, more fortunate, share our bed with a kindly person who switches on the light, makes us a cup of tea, and holds us close. Such love can make our terror recede like the tide, but, like the tide, it can return, and there is no good parent there to pick us up and cuddle us and assure us that the world is a safe place and there is no reason to be afraid. We are grown up now, and, try as we might to deny it, we know the loneliness of being. We long for good parents who will rescue and love us, but we know that there are no good parents and, while we might believe in God the Father, in these times of terror He is far away.

For some people the waves of terror and the sense of annihilation last for many minutes. Some people move very quickly to turn the terror into all kinds of manageable worries - manageable not because the worries are about problems which can be solved but because they turn a nameless terror into a named anxiety. Thoughts like ‘Who will look after me when I get old?’, ‘I can’t manage the tasks I have to do at work today’, ‘The lump on my groin is certain to be cancer’, ‘If my daughter goes to that school she’ll get mixed up in drugs’, ‘I won’t be able to meet this month’s bills’, ‘I should have done more for my parents before they died’ are indeed terrible, but they give a sense of structure and have a common, everyday meaning. With these common, everyday meanings we can pretend that the terror we felt did not happen, and that we belong to the everyday world.

However, not everyone can do this. For some people, lying there in the dark, the terror goes on and on. When Edith described to me how this happened to her she said, ‘It gets so bad I think I shall run outside the house in my nightie and stand in the middle of the road so I’ll get run over and that’ll stop it.’

‘Not in your street at 2 a.m. you won’t,’ I said, knowing how empty her town was at night. I went on to tell her that the terror she felt is called ‘existential angst’. She laughed at this ridiculously pretentious name. ‘I’ll remember that next time,’ she said, ‘I’ll lie there and think, “I’m experiencing existential angst.’“

I do hope she does, and finds her laughter in the midst of her terror. It would be so monstrously unfair if Edith followed the path of a woman whose inquest was reported in the paper recently. She was an elderly patient, not long discharged from a psychiatric hospital. A nurse told the coroner that she had looked in the patient’s room at midnight and seen her sound asleep. When she returned at 6 a.m. she found her floating in the bath. The coroner returned an open verdict. There was no mention of the terror which the poor woman could bring to an end only by filling the bath with water and, all alone, immersing herself in it. When fear is terrible, all we can do is run away.

Fight or Flight

Fear has a vital life-saving function. It is the means by which our body mobilizes itself to move swiftly and efficiently to protective action. When we interpret the situation we are in as dangerous, adrenaline, which is produced by the adrenal glands just above the kidneys, as well as at the ends of the neurones in the brain, is pumped into our system, thus causing our heart rate, blood pressure and blood sugar level to increase, and so preparing the body to fight or flee. If we act physically, by striking out at the source of the danger or by taking to our heels and running away, then we make use of our body’s preparations. But if we neither fight back nor run away we are left with the effects of these preparations and they can be most unpleasant.

Our heart beats fast and we feel shaky, sweaty and tingly. Some people experience severe headaches, some feel nauseous, some feel dizzy and close to fainting. Some people do faint. When these reactions occur in company, where we need to be calm and collected, we can feel very ashamed of ourselves. When they occur and we do not know why, we can feel frightened and so start on the sickening cycle of fearing fear itself.

Faced with an external danger, such as a man carrying a gun, or an oncoming monstrous tsunami, we can stand and fight or flee. However, sometimes the people around us will not let us do either. Children who are frightened of their parents or teachers may be prevented from either fighting to protect themselves or running away. Lacking the means to support themselves or their children, women may be unable to flee from husbands who frighten them. Needing to support their families, men may be unable to fight or flee from employers who frighten and mistreat them.

Thus it is very easy to find ourselves in a situation where we wish to fight or to flee but feel that we can do neither. Such a conflict leaves our mind in a turmoil and our body reacting appropriately to our reading of the situation (danger) and inappropriately to our reaction to our reading of the situation (neither fighting nor fleeing).

If we can make such a conflict explicit, by thinking about it very clearly and honestly and by discussing it with understanding friends and counsellors, then we can often find a way to solve the conflict or to live with it more easily. But if we dare not make the conflict explicit to others or even to ourselves, then we cannot resolve it and our misery goes on.

Shirley came to see me because she was nervous. She had given up driving because she was frightened she would have an accident and hurt someone.

‘I’m not worried about hurting myself. It’s other people that I worry about.’

She felt nervous when she had to go into a room where there were other people.

‘I worry that they’ll all look at me. Yet I like going out and having a social life. It’s just I sort of feel ashamed. I don’t know why. I do go out, like we go out for a drink, and I find my hands shaking.’

She said that what she wanted was to feel more confident.

‘I’ve never felt confident.’

Her brothers, all older than her, used to tell her that, as she was a girl, she could not play with them. At school her teachers told her that she was not bright.

‘I mightn’t be brainy but I’m intelligent. That’s what I’m always telling my husband. He treats me like I’m stupid and don’t know anything. But you can’t tell him. He’s one of those men who always have to be right. Don’t get me wrong, he’s a wonderful husband and thinks the world of me, but he does put me down.’

She spoke of how important it was to her to be herself, to have a small job so she had some money of her own, and how annoyed she got with herself when she became too nervous to do the things that she wanted to do. Yet, when she spoke of being confident, there was some sense of reservation. She would not want to be totally confident.

Why was that? Well, a great deal is expected of totally confident people. People expect them to be able to cope with everything. Shirley’s problem was that if she became totally confident she would be asked to do things which she could not or would not do, and she did not want to say no to people.

‘I don’t like to upset people. I want to be liked.’

If Shirley’s problem had been simply that she lacked self-confidence, then she could have solved that problem by taking steps to increase her self-confidence, but if she also believed that if she was self-confident she would upset people and they would dislike her, she could not afford to become self-confident.

Unavoidable Conflicts

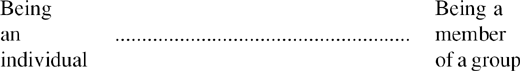

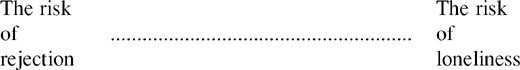

Shirley’s conflict is one which many people experience. We want to be ourselves, but we fear that if we do express our own wishes, needs and attitudes, then people will not like us. For some people being liked is not their top priority, but for many people it is a matter of life and death. More of this later. Here I want to point out that all of us, whatever we feel about being liked, are always involved in finding a balance somewhere between

If we live completely as an individual pursuing our own interests and taking no account of other people’s needs and wishes, we soon become extremely lonely. If we live completely on our own, lacking the checks and balances that other people place on our interpretation of what goes on in the world, we become an extremely idiosyncratic person whom other people regard as odd, even mad. On the other hand, if we merge ourselves completely with a group we cease to be the person we are. We become a nothing. Rather than face either of these fates we have to find a balance, day by day, between being an individual and maintaining relationships with other people.

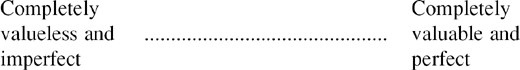

In finding a practicable balance between being an individual and being a member of a group, you have to arrive at a balance between regarding yourself as

The more we regard ourselves as valueless and imperfect, the more we fear, hate and envy other people, the more we feel frightened of doing anything, and the more we fear the future. Regarding ourselves as bad brings a lot of troubles. Yet if we regard ourselves as perfect we delude ourselves and make it difficult for other people to get along with us. No one is perfect. We all make mistakes, get things wrong, irritate other people, and fail to make the most of our talents.

So we have to arrive at a realistic assessment of ourselves, with no false modesty, seeing ourselves as ordinary people, like all other people, yet at the same time as individuals who are valuable to ourselves and to other people, even though other people may not value us in the way that we want them to value us.

It can take us many years to arrive at an assessment of ourselves which provides a realistic and hopeful balance between imperfection and perfection. We can be plagued by doubt, confused by the conflicting demands that people make on us, and hurt by criticism. To find out who we are and how we should assess ourselves we need to explore, to meet new people, to try out new situations and to see how we feel and react to and deal with the strange and the new. But to do this, we need freedom, and to have freedom we have to give up security.

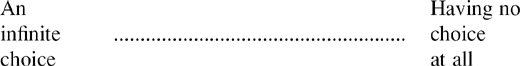

From the moment of our birth, we have to find a balance between

The more freedom we have, the less security. The more security, the less freedom. Total freedom means total uncertainty and great danger. Total security means total certainty and total hopelessness, for hope can only exist where there is uncertainty.

We all try to hold on to a measure of security. Most of us do this by having possessions (what is that line from a song - ‘Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose’?), just as most of us find security by keeping close to a group of people (why else would we put up with awful relatives?). Some people seek security not just in possessions and people but in a set of beliefs which makes everything that happens part of a pattern. The pattern may be in terms of heaven and hell, or Allah’s will, or karma, or fate, or a constellation of stars, or the eventual victory of the proletariat, but whatever the pattern is, it gives us a sense of fixity in what would otherwise seem to be a meaningless chaos.

However, while having a belief in some kind of grand design can give a sense of security, it can make the person who holds the belief feel hopeless. If the pattern of your life is already determined by God or by your stars, or by your genes, or by your parents, or by a series of rewards and punishments called conditioning, then there is nothing you can do to change it. You are helpless and hopeless.

On the other hand, if nothing is fixed, if anything can happen, at any time, then you have an infinite number of choices about what you do with your life. Such freedom can be exciting if you have lots of confidence in yourself, but if you do not, then such freedom is very scary. So, somehow, we all have to achieve a balance between

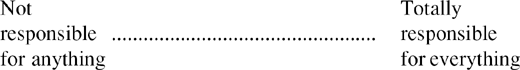

Along with the question of choice comes the question of responsibility. How much are we responsible for what happens? If we are just acting out a pattern which was determined and fixed in our stars or in our genes before we were born, then we are not responsible if we turn out to be murderers or thieves, and it is not our fault if our children turn out badly or millions of people starve. Such a release from responsibility can seem quite attractive, but, equally, if we are not responsible for when things turn out badly, we cannot take the credit for when they turn out well. You cannot take the credit when you become rich, famous and powerful, when your children lead happy, successful lives, and when you solve the problems of world hunger and nuclear war. So, being responsible does have its benefits.

But where does that responsibility end? You might be responsible for doing your work properly but are you responsible when the firm you work for goes bankrupt and you lose your job? You might be responsible for looking after your children, but are you responsible when your daughter’s marriage breaks up or your son gives up his job to go surfing in California? You might be responsible for organizing your finances so that you have some money to give the charities, but are you responsible for those world events which give rise to hunger, terrorism and war?

So we have to find a balance between being

Even though from the moment of birth we need other people, as small children we soon learn that other people can reject and punish us, and this can be very painful. We protect ourselves from this pain by becoming very careful in our relations with other people. We withdraw from them, and when we deal with them we put on some sort of social front. When I was researching for my book Friends and Enemies1 I questioned a large number of people about the part friendship played in their lives. Many of these people spoke of how, while they valued their friends and dreaded loneliness, they feared being rejected or abandoned or betrayed by their friends. Being close to other people is risky, but then we also run the risk of loneliness.

So we have to find a balance between

Thus in these six vital aspects of our lives we are for ever trying to achieve a balance between two opposites. There is no textbook we can consult which will tell us what is the right balance, because what is right for one person is wrong for another. We cannot, when we are, say, fifteen, arrive at a set of balances which will suit us for the rest of our lives and stick with that, because what is a good balance at fifteen is not so good at twenty and quite disastrous at forty. So we have to keep trying to find the right balance, and we always run the risk of getting it wrong. We are always in the position of the juggler who is trying to keep eight oranges in the air while balancing on a ball which is on a chair which is resting on a plank which is supported by two rolling drums which are on a raft floating in deep water. Any minute, something could go wrong. It is no wonder that we often feel frightened.

We struggle on, meeting what seems an endless stream of difficulties and problems. When we encounter yet another setback, we often look at other people and see them being like those people in the television advertisements who are always beautiful, knowledgeable, organized, intelligent, happy, loved, admired and suffering no greater problems than choosing the right margarine and coping with the weather. Then we can feel just like Alice when she met a couple at a dinner party.

‘They’ve got three children,’ she told me, ‘and they’re all brilliant, marvellously musical, getting excellent degrees, entering wonderful careers. He’s done terribly well, she’s got this marvellous part-time job and she’s got paintings in this new exhibition. Everything that family does is just right. Urgh!’

It is hard not to feel envy for people whose lives seem to go along more easily, more successfully than ours. However, this is the price we pay for clinging to the hope that it is possible for us to find a way of life where we are happy, trouble free and never make a mess of things. Without this hope many of us would find life very difficult indeed. The alternative version of life, in which all of us suffer one way or another, have heavy burdens and often make a mess of things, can rob us of hope and make us feel very frightened.

Many of us, as we get older, come to agree with Samuel Johnson that ‘Human life is everywhere a state in which much is to be endured and little to be enjoyed’, and try to meet this view of life with courage and hope. However, those of us who have read about Johnson know that during his life he was often depressed and that he was always afraid of dying.

Fear of Life and Death

Most of us go through a large part of our lives not thinking about death. ‘When it comes, it comes,’ we say, and secretly think that it will not. Other people die in earthquakes or car accidents or of cancer or of old age, but not me. I am the exception. Then one day something happens and we know. Death means me.

Then all the careful security we have built up comes crashing down. We are all alone, without protection, open to great forces which we cannot and do not understand. We ask in our anguish, ‘Why me?’ ‘Why death?’ ‘Why life?’ ‘What is it all about?’ There are no satisfactory answers.

From the moral and religious education we received in childhood many of us drew the comforting conclusion ‘If I’m good nothing bad can happen to me or to my loved ones’. When death becomes imminent, or some other terrible disaster strikes, our belief in the protective power of virtue is swept away.

Rose’s lawyer asked me to prepare a report on how Rose had been affected by her accident. She was having difficulty in getting back to work.

Rose said to me, ‘The car pulled out of the driveway and hit me as I was cycling past. My bike was caught under the front of the car and I was pushed across the road. I could see the lights of other cars coming towards me. I remembered how, when I was eight, we left our beautiful home in the country and moved to London. And then I thought, “I won’t have any more holidays.” I ended up in the gutter on the other side of the road. A man came to pick me up and I thought he was the driver of the car. I gave him a mouthful. I was angry and then I found that he wasn’t the driver… I feel so guilty about all of this, putting all you people to so much trouble. You’ve got people who need your help far more than I do. I’m all right, really, just my back’s a little sore and I get a bit weepy now and then. I usen’t to be like that. Always self-controlled, really. Now I think, why me? Why do I go on living and those babies die?’

Rose was not all right. She was shaken to the very core and guilty that she was alive. That sounds crazy, but it is what many people think when they have survived a terrible disaster. ‘Survivors’ guilt’ is now a common term, derived from studies of the people who survived the concentration camps of the Second World War, or Hiroshima and Nagasaki (the hibakusha), or the fighting in the Vietnam War.2 Such people feel, not joy at being alive, but fear, fear that they have done something wrong, for they ought to have died like their companions, fear that they have been given something they do not deserve and that they will be punished for holding on to it or that it will be suddenly taken away from them. They may have survived, but death as retribution is imminent.

Rose’s question ‘Why me?’ was that of an ordinary woman nearing sixty who had worked diligently all her life, looking after her family, being competent in her office work, enjoying a quiet life in a country town, never expecting that her life would have any other significance than the pattern of the lives of her family and friends.