Полная версия

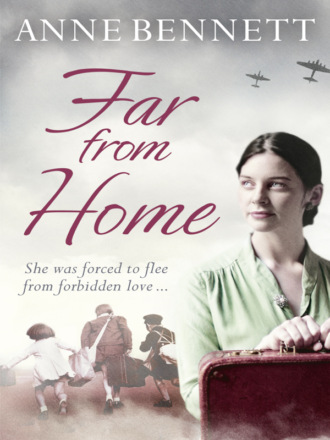

Far From Home

‘And whenever you write you always seem to be having such a fine time of it,’ Sally went on. ‘I just decided on the spur of the moment to come over and see for myself. It wasn’t something I planned or anything, it was just that I knew I would never get such a chance again. It’s seldom I have the farmhouse to myself.’ Then she glanced up at Kate and said, ‘I left them a note, tried to explain …’

‘I doubt that will help much,’ Kate said. ‘And I do feel sorry for you, but I can’t have you here, not like this. Really, this isn’t the way to get more freedom. Your best bet is to write to Mammy and Daddy and say how sorry you are and make your way home again sharpish. Later, when the time is right, I will plead your case for you.’

‘Oh, will you, Kate?’ Sally cried. ‘That will be grand. Mammy listens to you. But I can’t write to her. She will be so cross with me.’

‘Yes, and with reason, I’d say,’ Kate snapped. ‘Don’t be so feeble. Go home and face the music.’

‘I can’t,’ Sally cried in anguish. ‘And anyway, I haven’t any money left, or not enough for the whole fare anyway.’

‘Oh, Sally,’ Kate cried in exasperation. Keeping her temper with difficulty, she took a deep breath and said, ‘I cannot have you here and that’s final, so I suppose I shall have to loan you the money, but for now you write a letter to Mammy saying how sorry you are and promise that you will make it up to her. You know the kind of thing to say. And I would just like you to know that you have wrecked my evening good and proper, because I was going dancing with Susie Mason tonight, like we do every Friday, and now I will have to pop along to see her and cancel our plans. I shouldn’t think she’ll be best pleased either.’

‘Sorry, Kate.’

Kate sighed. Sally was an irritating and quite selfish girl, but she couldn’t keep telling her off. In a few days she imagined she’d be on her way home and not her concern any more and, though her parents had always doted on her, or until James’s birth anyway, she knew that her mother at any rate would roast her alive for this little adventure. So she looked at her sister’s woebegone face and said, ‘On the way home, for all you don’t deserve it, I will buy us both a fish and chip supper.’

‘Oh, will you, Kate?’ Sally cried. ‘I would be so grateful. I haven’t eaten for hours.’

‘That’s why you’re so tearful,’ Kate said. ‘A full stomach always makes a person feel more positive. I’ll get going now and I’ll not linger because I’m hungry myself. Write that letter and make sure you have the table laid and the kettle boiling by the time I get back.’

Susie was disappointed, but she could see Kate was too. ‘And she just turned up like that?’ she repeated, when Kate told her what Sally had done.

‘That’s right,’ Kate said. ‘She was waiting for me when I got in from work and admitted she’d sneaked out when both our parents were out of the house and James at school. Claimed she left a note explaining it.’

‘Explaining what?’ Susie said. ‘Why did she do it?’

‘Oh, that’s the best yet,’ Kate said. ‘She said she was fed up. Like I said, we all get fed up. The trouble is she overheard Mammy telling someone after Mass that she would never let her come here, even for a little holiday. I suppose it was like the last straw for her – and then she got the opportunity with everyone out of the way, so here she is. She can be very headstrong,’

Susie nodded her head. ‘She was always spoiled though, wasn’t she?’ she said. ‘I saw that myself when I came to stay with my granny when my mother was in the sanatorium that time. Even as a small child she usually got all her own way.’

Kate remembered that time well. Susie Mason’s mother, Mary, had been very ill when Susie was just ten and she had been sent to be looked after by her mother’s granny in Ireland while the older boys, Derek and Martin, stayed at home with their father. In Copenny National School, just outside Donegal Town, where the Munroe children all went, Susie was put to sit beside Kate, who had been strangely drawn to the girl who seemed so lost and unhappy. She had once confided to Kate that she was scared she would never see her mother again and Kate thought that the saddest thing. And so did Philomena when she heard. From that moment, Susie was always made welcome in their house.

Susie’s mother did recover, however, although Susie had been living in Ireland six or seven months before her father came to fetch her home. By then a strong bond had been forged between Kate and Susie. They wrote to each other regularly, and when Susie came back on her annual holiday, they would meet up whenever Kate could be spared.

‘My mother said that you do a child no favours by giving in to them all the time,’ Susie said to Kate.

‘And she’s right,’ Kate said. ‘But there’s not much I can do about that. And now I’d better go and get those fish and chips before I fade away altogether. Can you hear my stomach growling?’

‘Course I can,’ Susie said. ‘It sounds like a disgruntled teddy bear. But before you go, here’s an idea: shall we show your sister round Birmingham tomorrow?’

‘Oh, I don’t know …’

‘We may as well,’ Susie said. ‘I mean, you can’t send her home till you hear from your mother, so what are you going to do with her otherwise? If we go late afternoon, we can stay on to see some of the entertainment in the Bull Ring – if it isn’t too cold or raining.’

‘All right then, yes,’ Kate said. ‘It will make up for not meeting up tonight. We’ll come round about half two, then. Give me time to do the washing and clean up the flat a bit first.’

‘All right,’ Susie said. ‘See you then.’

So that evening, as they ate the very welcome fish and chips, Kate said to Sally, ‘How would you like to go into town tomorrow? We can show you round and then take you down the Bull Ring. You mind I’ve told you about it in my letters?’

‘Yes, oh, I’d love to see Birmingham,’ Sally said. ‘And you said the Bull Ring was like a gigantic street market.’

Kate smiled. ‘Yeah, like Donegal Town on a Fair Day, only bigger – but without the animals, of course,’ Kate said.

‘And yet it’s called the Bull Ring?’

‘I never thought of that,’ Kate said with a shrug. ‘I suppose they must have sold bulls there at one time. There’s all sort of entertainment on offer there when the night draws in. I’ve told you about it in my letters.’

‘Yeah. You said it was all lit up with gas flares so it was like fairyland,’ Sally said. ‘So what sort of entertainment? You never said much about that.’

Kate made a face. ‘I wasn’t sure Mammy would approve,’ she said. ‘It isn’t wrong or anything, but sometimes Mammy takes a notion in her head to disapprove of something and that’s that then, so I was always very careful what I wrote. Anyway, you’ll see for yourself tomorrow, though I’m warning you now we’re not hanging about too long if it’s freezing cold or raining or both. There’s no pleasure in that.’

‘I still want to go,’ Sally said. ‘Ooh, I can’t wait.’

Kate laughed. ‘You’ll have to,’ she said. ‘And first thing tomorrow we have to clean the flat and do the washing. It’s the only day I have to do all this.’

‘I’ll help if you tell me what wants doing,’ Sally said. ‘It won’t take so long with two of us at it.’

‘No it won’t,’ Kate said, getting up and pulling her sister to her feet. ‘Come on,’ she said suddenly. ‘You tidy up here and I’ll nip out and post your letter and then we can hit the sack, because what with one thing and another, I’m whacked.’

A little later, as they were getting ready for bed, Kate said, ‘Susie is coming with us tomorrow. We’re meeting her at half past two.’

Sally made a face. She would hate Susie to be annoyed with her, because she had always admired her when she’d come to Ireland on holiday. Sally remembered her as having really dark wavy hair that she had worn down her back, tied away from her face with a ribbon like Kate’s. It had been a shock to see that now Kate braided her hair into a French plait and fastened it just above the nape of her neck; she told her that Susie wore hers the same way.

‘Ah, I liked her hair loose – and yours too,’ Sally said regretfully.

‘We would be too old to wear our hair like that now,’ Kate told her as she loosened the grips and began to unravel the plait. ‘Besides, in the factory, I have to wear an overall and cap that covers my hair, so wearing it down isn’t an option for either of us any more. Anyway, it really suits Susie, because she always has little curls escaping and sort of framing her face. Most of the rest of us look pretty hideous.’

‘She’s pretty though, isn’t she?’ Sally said. ‘I mean, her eyes are so dark and even her eyelashes and eyebrows are as well.’

‘She takes after her mother,’ Kate said. ‘Her brothers look more like their dad. Pity about her snub nose, though.’

‘Ah, Kate.’

‘I’m not speaking behind her back, honestly,’ Kate said as she began to brush her hair. ‘She would be the first one to tell you herself. Anyway, her mouth makes up for it because it turns up by itself, as if she is constantly amused about something, so people smile at her all the time.’

‘I know,’ Sally said, ‘I can remember – and her eyes sparkle as well. I used to love her coming on holiday because she used to liven everyone up. And her clothes always looked terribly smart, too. I really like her. I hope she won’t be cross with me because I spoiled your plans for tonight?’

‘No,’ Kate said assuredly. ‘Susie’s not like that. Come on, let’s get undressed. It will be funny sharing a bed with you again.’

‘It will be nice,’ Sally said as she pulled her dress over her head. ‘Cuddling up in bed with you was one of the many things I missed when you left home.’

‘I wouldn’t have thought you missed anything about me that much.’

‘Oh, I did,’ Sally said sincerely. ‘I was real miserable for ages.’

Kate saw that Sally really did mean that, and she realized she had never given much thought to how lost Sally might have felt when her big sister just wasn’t there any more. But she didn’t want her feeling sad or to start crying again, and so she said with a smile as she climbed into bed, ‘Come on then. Let’s relive out childhood memories – only it might be squashed rather than cosy because you’re bigger now than the strip of wind I left behind three years ago.’

‘I think the bed was a lot bigger too,’ Sally said, easing herself in beside her sister. ‘Still nice though.’

And it was nice, Kate had to agree, to feel a warm body cuddled into hers on that cold and miserable night. She was soon asleep. Sally, though she was tired too, lay awake listening to Kate’s even breathing and the city noises of the night. Slade Road, Kate had told her, was quite busy most of the time because it was the direct route to the city centre. And it was busy, and Sally didn’t think she would sleep with all the unaccustomed noise from the steady drone of the traffic, overridden by the noise from the clanking trams and rumbling lorries. As she lay there listening to it, her eyelids kept fluttering closed all on their own, and eventually she gave a sigh, cuddled against Kate and, despite the noise, fell fast asleep.

TWO

The next morning, Sally woke with a jerk; she lay for a moment and listened to the city beginning the day. Then she climbed out of bed and walked across to the window. Though it was early enough to be still dusky, traffic had begun to fill the streets on both sides of the road, where horse wagons and carts vied for space with motor vehicles, and trams clattered along beside them. The clamorous noise rose in the air and filtered into the flat. The pavements too seemed filled with people and she watched some get off trams and others board them from the tram stop just up the road from Kate’s flat, while others hurried past with their heads bent against the weather.

She sighed as she leant her head against the windowpane. There were so many people and so much noise that she didn’t think she would ever get used to actually living here. She reflected on what it was like to awake in the farmhouse. The only sound after the rooster crowed was the cluck of the hens as she threw corn on to the cobbles in the yard, the occasional bleat of a ewe searching for her lamb, the odd bark of the dogs, or the lowing of the cows as they gathered in the fields for milking.

Birmingham seemed such an alien place, and yet Kate had seemed to settle into it so well. Now Sally was anxious to see the city centre; the previous evening she had been too distracted and it had been too dark to get more than just a vague impression.

In the cold light of day she wondered what on earth had possessed her to take flight. Why hadn’t she at least tried to talk to her parents? Tell them how she felt? Maybe if she had explained it right they would have agreed to let her spend a wee holiday with Kate the following spring when she would be seventeen. Well, she thought ruefully, God alone knew when she would ever get the chance again. She imagined, after this little caper, her mother would fit her with a ball and chain.

In her heart of hearts she had known she had made a terrible mistake as soon as she had seen the grey hulk of the mail boat waiting for her as she alighted from the train in Dún Laoghaire. Ulster Prince, she’d read on the side, and she had almost turned back then, but the press of people behind her had almost propelled her up the gangplank and on to the deck, which seemed to be heaving with people.

She hadn’t been on the deck long when there was a sudden blast from the funnels and black smoke escaped into the air as the engines began to pulsate and the deck rail to vibrate as the boat pulled away from the dock. Sally watched the shores of Ireland disappear into the misty, murky day, and wished she could have turned the clock back. She felt her insides gripped with a terrible apprehension, which wasn’t helped by the seasickness that assailed her as the boat ploughed its way through the tempestuous Irish Sea. Cold, sleety rain had begun to fall too, making it difficult to stay outside. Inside, however, the smell of whisky and Guinness mingled with cigarette smoke, and the smell of damp clothes and the whiff of vomit that pervaded everywhere made her stomach churn alarmingly, while the noise, chatter, laughter, singing and the shrieking of children caused her head to throb with pain. Like many of the other passengers, she’d ended up standing in the rain, being sick over the side of the mail boat. By the time she’d disembarked and thankfully stood on dry land again, she had never felt so damp or so wretched in the whole of her life.

She tried to gather her courage as the train thundered along the tracks towards Birmingham. She told herself that – even if she was cross with her – Kate would look after her and make everything right, because she always had in the past. But she was so unnerved by her own fear and the teeming platform that she was almost too scared to leave the train at New Street Station – she had never seen so many people in one place before.

She’d never heard so much noise either. There was the clattering rumble of trains arriving at other platforms and the occasional screech and the din from the vast crowds laughing and talking together. Then there were porters with trolleys loaded with suitcases warning people to ‘Mind their backs’. A newspaper vendor was obviously advertising his wares, though Sally couldn’t understand a word he said, and over it all were equally indecipherable loudspeaker announcements.

She felt totally dispirited as she breathed in the sooty, stale air, but she knew that if she didn’t soon alight, the train would carry her even further on, and so she clambered out on to the platform, dragging her case after her. She realized that the boldness that had enabled her to get this far had totally deserted her, and she had no idea where to go or what to do next. She looked around, feeling helpless and very afraid.

Most people were striding past her as if they were on some important errand; they seemed to know exactly where they were going, so she followed them and in minutes found herself in the street outside the station. If she had been unnerved inside the station, she was thoroughly alarmed by the scurrying crowds filling the pavements and traffic cramming the roads outside it. The noise too was incredible and she stood as if trans-fixed. There were horse-drawn carts, petrol-driven lorries, vans, cars and other large clattering monsters that she saw ran along rails – she remembered Kate had said they were called trams – all vying for space on the cobbled roads. And because of the gloominess of the day, many had their lights on, and they gleamed on to the damp pavements as she became aware of a sour and acrid smell that lodged at the back of her throat.

How thankful she had been to see taxis banked up waiting for passengers just a short way away. Not that she was that familiar with taxis, either; in fact she had never ridden in one before. It didn’t help that the taxi driver couldn’t understand her accent when she tried to tell him where her sister lived and she had to write it down.

Eventually, he had it, though, and Sally had gingerly slid across the seat, and then the taxi started up and moved into the road. She looked about her but could see little, despite the pools of brightness from the vehicles’ headlights and the streetlamps and lights from the illuminated shop windows spilling on to the streets, because low, thick clouds had prematurely darkened the late afternoon.

And then when Sally had arrived at the address that Kate always put on her letters home, the door had been locked, so she’d lifted the heavy knocker and banged it on the brass plate. No one came, and no one answered the second knock either, but at the third the door was suddenly swung ajar and a scowling young woman peered around it. In the pool of light from the lamppost, Sally could plainly see the scowl. And she demanded brusquely, ‘What d’you want and who are you anyway?’

‘Kate,’ Sally said, unnerved by the woman’s tone. ‘I want to see Kate Munroe. I am her sister from Ireland.’

The woman’s voice softened a little as she said, ‘Are you now? Kate never said owt about you coming.’

‘She didn’t know.’

‘Nothing wrong I hope?’

Sally shook her head. ‘I just wanted to give her a surprise.’

The other woman laughed. ‘Surprise?’ she repeated. ‘Shock more likely. Any road, she ain’t here, ducks. She lives upstairs but she won’t be in yet. She’s at work, see, and I think she comes home at six or thereabouts.’

‘Oh.’

‘You’d best wait for her here,’ the woman said, ushering her into the entrance hall. ‘I would take you into my place, but I’m off to work myself ’cos I work in a pub, see. I was getting ready, and that’s why I was so mad at you nearly breaking the door down.’

‘Sorry.’

‘Well, it ain’t your fault,’ the girl conceded. ‘But if I hadn’t opened it I don’t reckon you would have got in at all because I don’t think anyone else is in from work yet.’

‘So, can I wait for Kate here?’

‘Oh yeah, no one will stop you doing that,’ the woman said. ‘And she’ll be in shortly, I would say. Any road,’ she said, ‘I got to be off or I’ll be getting my cards. Might see you around if you’re staying a bit.’

It was very quiet when the woman had gone, and dark and quite scary, and Sally wished she hadn’t had to leave. But she didn’t want to take a chance on meeting any more of Kate’s neighbours until she had met Kate herself and gauged her reaction, since she had a sneaky feeling that Kate wouldn’t be as pleased to see her as she might have hoped. And so she had slunk under the stairwell and sank into a heap and, totally worn out, had fallen into a doze.

Sally had gauged Kate’s reaction very well. She had been very angry, and remembering that now, Sally decided to get dressed and start to help in the hope she might put her sister in a better frame of mind. She wanted them both to enjoy their day in Birmingham. She sorted out clothes from the case on the floor, as Kate had said there was no point in unpacking it, but, quiet though she was, Kate heard her and turned over. ‘You’re an early bird.’

‘Yeah, suppose it’s living on a farm,’ Sally said. ‘Anyway, you said that there was a lot to do today before we can go and meet Susie.’

‘And so there is,’ Kate said, heaving herself up. ‘And I suppose the sooner we start, the sooner we’ll be finished. So we’ll have some breakfast now and then we can really get cracking.’

Kate was impressed with the enthusiasm Sally seemed to have for cleaning and tidying the flat and coping with the laundry, an attribute she had never seen in her before. By the time they were scurrying up the road to meet Susie, everything was done.

‘Don’t you mind the noise of all the cars and stuff?’ Sally suddenly asked Kate as they walked along.

‘You know,’ said Kate, ‘I seldom hear it now.’

Sally looked at her in disbelief. ‘You can’t miss it.’

Kate nodded. ‘I know. It’s hard to believe but that’s how it is now – though when I first came I didn’t think I would ever be able to live with the noise. But now it sort of blends into everything else.’

‘And what is that place over there on the other side of the street?’ Sally said. Trees, bushes and green lawns could just be glimpsed beyond a set of high green railings bordering the pavement.

‘Oh, that’s the grounds of a hospital called Erdington House,’ Kate said. ‘I always think that it’s nice it is set in grounds so that people can at least look out at green, which I shouldn’t think happens often in a city. But then I found that it once used to be a work house and maybe the people in there had little time for looking out.’

‘Maybe not,’ Sally said. ‘But it might have been nice anyway because I imagine any green space is precious here, I have never seen so many houses all packed together.’

‘Remember, there are a lot of people living and working in Birmingham and they have to live somewhere,’ Kate said. ‘They have to shop somewhere too, and so while there are a few shops here on Slade Road, in a few minutes we will get to Stockland Green and you will see how many shops there are there – all kinds, too: grocer’s, baker’s, butcher’s, greengrocer’s, fish-monger’s, newsagent’s, general stores, post office; even a cinema.’

Sally was very impressed. ‘A cinema!’ she repeated in awe. ‘I’d love to see a film.’

Kate remembered how impressed she had been when she arrived here, knowing a cinema was just up the road. ‘You play your cards right and I just might take you tomorrow.’

Sally gasped. ‘Oh, would you really, Kate?’

Kate nodded. ‘And if there is nothing we fancy at the Plaza, we can always go to the Palace in Erdington Village – that’s just a short walk down Reservoir Road and over the railway bridge.’

‘Oh, anything will do me, Kate.’

‘Yes, I know, it’s just in case I’ve already seen it,’ Kate said. ‘Anyway, what do you think of Stockland Green? We’re coming to it now,’ and Sally was impressed to see that there really were all manner of shops virtually on the doorstep.

‘Oh, that’s a nice pub,’ Sally exclaimed as they came to the top of Marsh Hill where the Masons lived.

‘The Stockland,’ Kate said. ‘It does look nice, doesn’t it? Not that I’ve gone inside it, but Susie said that though it was built not that many years ago, it was based on the design of a Cotswold manor house.’ And then she gave a sudden wave because she saw Susie coming up the hill.

Susie had not seen Sally for three years because she had not been back to Ireland since Kate had joined her in Birmingham, but she was able to have a good look at her as she approached. The Sally she remembered had been little more than a child; she saw she was a child no longer, but a young lady. It was hard to believe that she was Kate’s sister, for they were so different.

Kate had always claimed that Sally was the beauty of the family, and while Susie had to own that she was pretty enough with her blonde curls, big blue eyes and a mouth like a perfect rosebud, she didn’t hold a candle to her sister. Kate didn’t see it in herself, but she wasn’t just pretty, she was beautiful. She also had a fabulous figure, while Sally was much plumper. Kate’s hair was dark brown, with copper highlights that caught the light, and her dark eyes were ringed by the longest lashes Susie had ever seen. She might have looked quite aloof, because she had high cheekbones and a long, almost classic nose, but her mouth was wide and generous and her smile was warm and genuine and lit up her eyes.