Полная версия

A Quiet Life

Copyright

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Copyright © Natasha Walter 2016

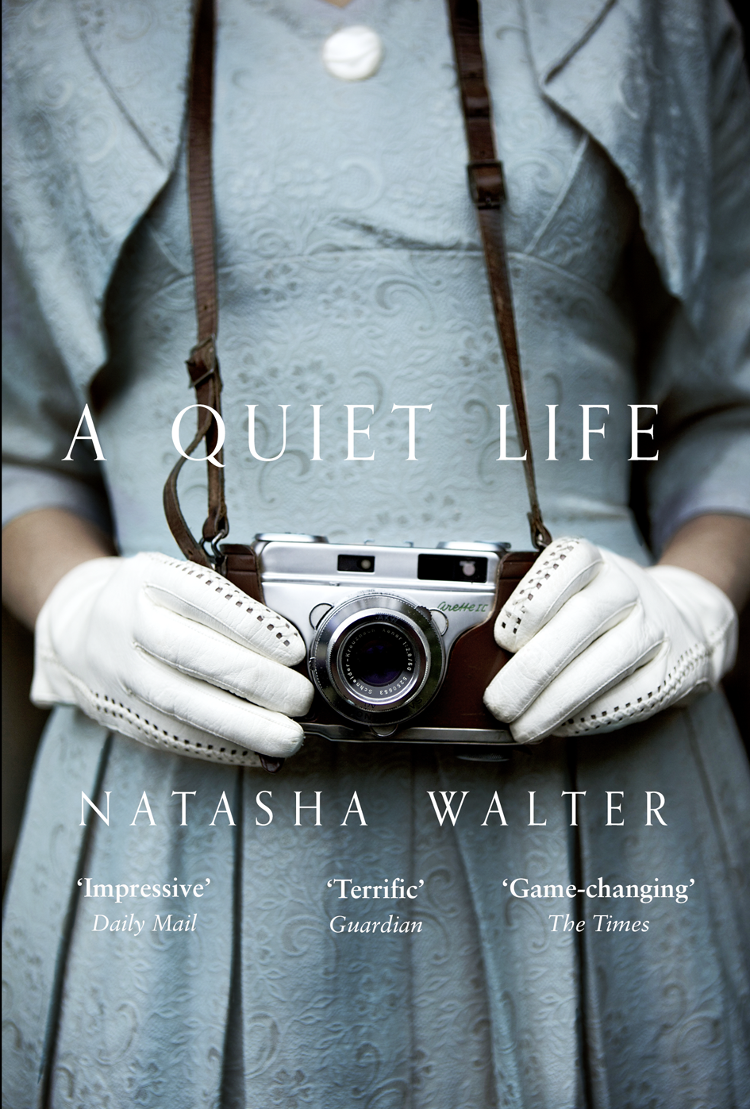

Jacket design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

Cover photograph © Jayne Szekely / Arcangel Images.

Natasha Walter asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780008113773

Ebook Edition © OCTOBER 2016 ISBN: 9780008113766

Version: 2016-11-24

Dedication

For Mark, Clara and Arthur

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue: Geneva, 1953

Water: To London, January 1939

Fire: London, 1939–1945

Earth: Washington, 1945–1950

Air: 1950–1953

Transition: August 1953

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Natasha Walter

About the Publisher

Prologue

Geneva, 1953

How slowly the light dies on these interminable summer evenings. Laura is so keen for each day to finish that she pulls dinner earlier every night. She hurries Rosa through her bath. ‘Rub a dub dub!’ she sings with some impatience as she towels her daughter’s hair. Rosa looks up, her flawless mouth half open, her dark eyes serene. ‘Dub dub,’ she repeats in a serious tone. Her hair is still damp, sticking up in spikes, as Laura settles her into her lap with a bottle of warm milk beside them.

The potatoes are already bubbling in their pan, the glass of cold vermouth is already poured and waiting at Laura’s elbow, the way to Rosa’s bedtime seems clear; but then the child suddenly pushes away the half-full bottle of milk and slides to the ground. ‘Open, open,’ she says, standing at the door that leads to the balcony. Laura fights her impatience as she lifts and encourages her – ‘Come on, my sweetheart, for Mama’ – to come back and finish her drink. ‘Nearly supper!’ she calls out to her own mother as Rosa finally drains it. Mother is reading some magazine on the sofa, still mapping the world of new autumn modes that will never be bought and new destinations that will never be seen.

Rosa is still saying ‘More!’ hopefully as Laura carries her up the awkward ladder staircase to her attic room. For a two-year-old, every evening comes too suddenly to an end. She is never in a hurry for the day to close. Laura lays her down in her cot with a solitary white rabbit for company. ‘More’: that was Rosa’s first word. My life is all run out, Laura thinks, stooping over the cot, but nothing is ever enough for you. Her daughter burrows into the mattress, face-down, a chubby starfish. Struck with unexpected guilt at wanting to hurry her into unconsciousness, Laura whispers, ‘Lullaby?’ But Rosa is gone suddenly into sleep, that enviable sleep that ebbs and flows over her with unpredictable tides.

Then Laura is back downstairs again, standing in the kitchen in front of the stove. As she downs half of her second glass of vermouth, she prods at the potatoes, cuts some tomatoes roughly, slides slices of ham onto two blue plates, and that’s it. That’s supper. Her mother’s glance moves to the drink as she comes into the room. She doesn’t say anything, but in almost unconscious reaction Laura lifts the glass and finishes it as her mother sits down and waits to be served.

‘Potatoes, Mother?’

‘Just two, thank you – now, what time is it that you want to leave this weekend?’

They have been over this a dozen times, and Laura pauses before she answers. ‘It’s this Friday, we can get a train just after three. It’s quite an easy journey, really. Wine?’

‘No, not for me, not tonight. And he has booked the hotel, has he, this – Archie?’

‘That’s right. He said it would be quiet at the end of the season, but still fun. He’s got daughters himself, but doesn’t see much of them – I think he misses that side of things, family life.’

Laura goes on talking, reassuring her mother that the weekend will be easy, that Rosa will enjoy it, that all three of them, grandmother, mother and daughter, might have a good time. Laura’s voice is calm, yes, and measured too, until her mother breaks in again. ‘Have you remembered to tell the consulate where we’re going?’

‘Of course I have!’ There is something too emphatic in the response, and her fork falls with a clatter to her plate. As the women’s gazes meet, Laura tries to shift the tension in the room. ‘If another trip feels too much,’ she says, ‘you know you could stay here without me. Or you could always go back to Boston.’

Mother pushes at some tomato on her plate with her fork. ‘Would you like me to go?’

There is no answer to that. Yes, Laura thinks, I would like you to go; I would like not to have any need for you to be here. But her mother’s presence is essential. The idea of being quite alone with Rosa in this fragmented world, wandering around Europe, uncertain of her welcome from friends and acquaintances, seems impossible to her now. As soon as her mother mentions leaving, the reasons why they are both here, joined together in their uncomfortable little ménage à trois, are present in the room again. Laura is back in the days immediately after Edward left, the telephone ringing and ringing in the hall, the black Austin car parked in the driveway, the cameras popping as she drew back the curtains. But when she speaks again, her voice is light.

‘Why would I want you to go?’ There is even the suggestion of a laugh in her words, as though her mother is being ridiculous. ‘I think Talloires will be lovely this time of year. And you should see how much Rosa enjoys swimming now. Did I tell you what she said today? I was looking for a fresh towel and I took out the blue one that I used in Pesaro, and she said, ‘Like on holiday, I all sandy …’

What, Laura thinks, would we talk about, day in, day out, if we didn’t have Rosa, her life forcing itself up, like a tree cracking paving stones, between the hard, dulled edges of our misfortunes? As usual, the two women talk about Rosa’s new words, Rosa’s little habits, as they fork up their supper. Eventually Laura picks up the plates and carries them to the sink. In theory the nanny, Aurore, is meant to tidy the kitchen in the morning, but in practice, Laura puts away the evening meal. She hates catching Aurore’s disdainful look as she picks up the detritus from their pathetic suppers.

There is a slice of apple tart left over from lunch. Laura presses it on Mother, although her mouth waters as she looks at it. Boredom breeds greed. As soon as it is eaten, Laura refills her own wine glass and they go to sit in the little living room, on the uncomfortable slippery couch. They are talking now about whether they need to buy anything for the trip. Obviously, it is silly in their situation to waste money, but on the other hand, it is important to keep up appearances. Mother mentions that nylon is such a good material for packing, because it doesn’t crease, and Laura agrees, and wonders whether it is worth getting Rosa a new dress now, since she is growing so fast that the two sundresses bought for her at the beginning of summer are already short. They sound ordinary and at ease, for a few minutes, just a mother and grandmother chatting, the last holiday of the summer approaching. When a silence falls that seems hard to break, Laura twiddles with the knob of the big grey radio. It comes on with a rush of static. A sudden cry rises from the top of the flat, as this noise or something internal – a dream? wind? – breaks Rosa’s sleep. The tension flares in Laura’s body as she wonders whether to go upstairs, but this time she is lucky. Silence falls again, only broken by the chattering voices of a couple walking in the street below.

‘Well,’ says Mother. ‘Maybe it’s time for me to get some sleep too. It’s funny how tiring it is, doing nothing.’

‘Isn’t it?’

Mother pulls herself off the sofa. Her footfalls are so heavy, so flat. Laura recognises that she is being overly sensitive, that she is like a twitchy old husband, wincing almost deliberately at every example of his wife’s bad taste and clumsiness. But she can’t help herself. She is on edge as she listens to her mother in the bathroom, to the patter of her urine and the swoosh of the flush, and the endless coughs and rustles as she goes through her careful rituals of greasing her face and putting her hair under a net. At last her bedroom door clicks behind her. She turns in bed. She sighs. Laura walks into the kitchen and swings open the door of the icebox. Water is collecting under it, she notices for the twentieth time, and for the twentieth time she ignores it. She takes out the bottle of wine, still half full, and sloshes more into the glass.

I’m not, Laura tells herself, and never will be, one of those women who starts drinking in the morning and who looks ten years older than their age after six months of lonely self-comfort. But it surprises her how often she has to ask the wine-merchant in the rue des Alpes to deliver another crate, or a couple of bottles of whisky. A martini at lunchtime, a vermouth or two before supper, and then she finishes the evening, every evening, sitting out on the balcony, an empty bottle beside her, or a measure of whisky glowing in a tumbler.

Because the end of the day is the moment she longs for. When she can stop acting her part. When she can sit out on this iron balcony, looking out over the lake as it turns from the lucent blue of summer to the blank of complete darkness. In those empty moments she feels less alone than she does all day, because she has her past for company, and ghosts gather companionably around her in the dusk.

Until Edward left she rarely drank alone. He was the one to pour the first martini of the evening, the last whisky at night. ‘Cheers, big ears,’ he said sometimes, imitating that tedious couple who lived downstairs from them for a while in Washington. ‘Bottoms up,’ Laura would add, pretending to be the wife. She sits now, watching the darkness deepen, until she can no longer tell the mountains from the sky, until she can almost feel Edward’s presence beside her and almost believe he could hear her if she spoke.

Every day, she looks for a sign. She catches her breath on so many occasions. When the telephone rings unexpectedly, or when she comes back to the flat to find an envelope sticking up over the top of the numbered mailbox in the hall. But also when people look at her too closely, and she wonders, are they about to tell me they have a message, are they about to say, someone was looking for you yesterday? Today it was the sharp-featured woman who came into the shop where she was buying a new summer dress.

When she saw the turquoise dress with its wide white belt in the window, she had pushed open the heavy door in the overpriced boutique in the rue du Port. It was almost as good as she’d hoped, the shade taking the sallowness out of her face, and the in-and-out shape giving back to her, generously, the lines of her younger body. Just as she said, yes, I’ll take it, and turned to the changing room to put on her own clothes, another woman entered the shop. She didn’t look at the clothes, she just stood there for a second and looked at Laura through her spectacles. ‘Let me see,’ she said in French, ‘are you—?’ Laura stood, caught in the woman’s attention, hope rising as clear as a chime of music in the room. ‘No, I’m so sorry,’ she said. ‘How absurd, I saw you through the window and thought that I knew you from the lycée in Montreux.’

Laura bought the dress and went out into the sunlight. She walked through the city, blinking behind her dark glasses. Soon she was by the lake. Among the swans a toy was floating, a child’s boat with a stained silk sail, and to her surprise she picked up a piece of gravel from the sidewalk and threw it hard at the boat. She missed. Her hands curled into fists, she walked away, high heels clacking on the clean Swiss street, the shopping bag on her arm with the new dress all folded up in tissue paper, back to the sparse apartment where her mother and daughter were awaiting her return.

And when she comes in, it is the same as ever. Laura sinks as quickly as she can back into Rosa’s world. She has a new doll that Mother has bought her, a rather fabulous creation that says ‘Mama’ when you punch its stomach. She punches and punches, and the curious thing says ‘Mama Mama’ in its low hiccupping tones, and every time Rosa smiles. ‘Sad baby,’ she says. ‘Sad baby.’ ‘Maybe it’s happy,’ Laura says, taking it from her and cradling it, and singing one of the nonsense songs she has made up in the long evenings. ‘Lullaby, lullaby, sleepyhead,’ Laura sings, as her daughter watches her with sharp, bright eyes. And then Rosa takes it back and starts doing the same, crooning in her out-of-pitch singing voice, enunciating the words carefully.

Mother comes in at that moment. ‘Look, Mother, how wonderfully she plays with it,’ Laura says. She gets up, and immediately Rosa punches the doll again and then drops it and holds onto Laura’s legs. ‘Sing,’ she commands, ‘sing.’ And so Laura spends the rest of the afternoon singing to her and her doll, and whenever her attention wanders, Rosa complains, vociferously. ‘You give in to her too much,’ says Mother, with the confidence of the woman whose child-rearing days are long over and whose criticism must be accepted. Laura wonders if she is right. She sees disciplined mothers everywhere, mothers who can turn away easily from their children and pass them to the nannies or tell them to play on their own; but those mothers have lives of their own. What do I have, Laura thinks? Only these endless afternoons waiting to be filled.

Now, sitting on the balcony, in her mind she is explaining things to Edward, telling him how motherhood is so different from what they expected. For the two years of Rosa’s life she has done this day by day, saying to him in her head, ‘I cannot do this’ and ‘Look at this’ and ‘Help me’ and ‘How perfect’. She watches other fathers – disengaged, or authoritarian, or protective – and fits his character onto theirs, imagining herself telling him to let Rosa climb the slide – ‘She can do it!’ Laura says to him in her mind, ‘She did it!’ – or telling him that she is too young to learn table manners. And sometimes, when she hears Rosa in the night, and knows that she must swing her feet onto the cold floor and set off again to comfort her terrors or her thirst or her fever, Laura imagines that he will be there when she returns, to hold her as Laura is about to hold Rosa.

She is leaning against the iron balcony now, her cheek pressed against its cold hard edge. Down below, on the sidewalk, a young woman walks quickly. She is wearing a red dress and her shoulders are hunched, but as she passes under the street lamp her face jumps clearly into the light – she seems to be smiling. A memory of herself, a memory she cannot quite place, drifts through Laura’s mind, but before she can catch it Rosa’s cry rises again, and as she gets up she stumbles a little, and puts her hands to her temples, trying to press the drunkenness out of her mind. It doesn’t do to go drunk to a crying child, it makes you clumsy and angry. Is this another reason why I want my mother with me now? Laura wonders. Can I be trusted, even with the daughter I love?

As soon as she is picked up, Rosa pushes her hot face into Laura’s shoulder; if her sleep was disrupted by some dream, then her mother’s huge, warm presence is immediately reassuring. But although she stops crying, she refuses to go back to sleep for a long time; every time she is put down, she sits up again and when Laura tries to leave the room she yells furiously. ‘Sing, sing.’ Laura sings a melange of songs without rhyme or reason. ‘Saturday night is the loneliest night of the week,’ she ends up singing, but she can’t remember the rest of it, and goes on crooning vaguely, stroking Rosa’s tense, warm back with her palm.

When at last Laura feels her daughter’s muscles loosen and her breathing become stertorous, she gets up and realises how light her head feels and how heavy her limbs are. She is exhausted. She goes into her own room, drops her clothes to the floor and falls into bed. She hasn’t slept properly for a while, but tonight sleep comes with smothering power, as though somebody is pulling a blanket over her face. And when she wakes the next day, she is sweating, twisted up in the covers.

It is a bad morning; everything seems wrong. Rosa has slept too long and her diaper has given out, her bed is soaked. That is for Aurore to do, but it puts her in a terrible mood. Aurore is a skinny Swiss girl with a fierce manner, but when Laura first interviewed her she could see that she genuinely liked Rosa. Even now, although she grumbles about everything else, she strokes the little girl’s hair with a soft, light touch as she asks what to buy for lunch.

When Laura goes out onto the balcony, a cup of strong coffee in her hand, she sees the glass and empty bottle from the night before. She knows that Mother, who is sitting there, has seen them too. Mother is false and hearty, planning out loud what she is going to write in her weekly letter to Laura’s sister in Boston. ‘How do you spell Talloires?’ she says, as though eager to tell Ellen about the trip that is weighing heavily on both of them, and Laura spells it out laboriously as she drinks her coffee.

Rosa cries when Laura goes back into the living room to pick up her hat and purse to go out, but Laura disengages her daughter firmly from her legs and clatters down the steps in the apartment building. There is no elevator here. It is the cheapest rental they could find that still looked elegant enough not to be embarrassing. The dark staircase smells of different people’s cooking and the paint is peeling on the walls, but out on the streets Geneva’s quiet order reasserts itself. In the café opposite the waiter is twitching paper covers straight on the metal tables and the only person drinking coffee there is a woman in an irreproachable blue toque. Laura walks her usual way to the kiosk on the corner for the Herald Tribune, and then back again to the garage where her car is kept. She has arranged to meet her cousin Winifred for lunch at a restaurant that she has found up in a mountain village, yet another clean Swiss restaurant with panoramic views of the hills. It is fair to say that she is not looking forward to the lunch; she knows that Winifred wants to talk to her about her future, and she has had to listen to her peremptory judgements too often recently.

The brilliant August sunshine is harsh, and her little straw hat is no use against it. She rummages in her purse, but she has forgotten her sunglasses. She can’t face going back into the apartment to confront Rosa’s anger and her mother’s forced smiles again; whenever she leaves Rosa, she feels freed of some burden, and whenever she leaves her mother she is released from the part she is playing, even if only for the minutes before she meets someone else. She opens the door of the car and waits a few seconds for the hot air inside it to dissolve before she gets in and starts the engine. As she moves off into the road, she notices a small grey Citroën coming up behind her, which makes her self-conscious – she is naturally a careless driver, but even careless drivers pay more attention when there is someone close behind them.

The streets of Geneva and the lakeside road are crowded at this time, and the grey car drops back, but when she turns onto the road that ribbons up to St-Cergue there is no one driving but Laura, and she starts to go faster and faster, her mind running on something else altogether. She is thinking of the dress she bought yesterday and whether it will go with her prize acquisition for the summer, an electric blue cotton coat with a neat cut by Schiaparelli that Winifred had passed on to her as it was too small for her. Laura is wondering whether wearing it with something else blue will look so overdone it would be cheap, or, on the contrary, whether it would be just the right kind of over statement to be really chic, when suddenly a car behind her, another small grey motor – or is it the same one? Even in the moment she registers the parallel – overtakes her and then brakes, completely without warning, in front of her. Laura brakes too, so suddenly she stalls, and she realises how carelessly she must have been driving. She flings open the door without thinking, adrenaline propelling her out.

‘What are you doing?’ she yells. She realises she is in the wrong language. ‘Qu’est-ce que vous faites? Vous conduisiez comme un fou!’

‘Mrs Last?’

The driver says her name through his open window, and Laura just says ‘Yes’ without thinking, and then he is opening his door too and they stand for a moment, and then she is back in her tirade, ‘Vous allez nous tuer tous!’

‘Mrs Last, my friend has something to show you.’

There is another man in the car, whose face Laura cannot yet see. He pulls down his window and leans out; he is middle-aged, wearing a squashy grey hat and an overcoat which is too heavy for this sunny afternoon.

All of a sudden Laura is aware that there is no one else here. No cars are passing. There are two of them; their car is blocking hers. They could do anything, anyone could – her purse is on the front seat of her car, and the door is still open.

She takes two steps backwards, her hand reaching behind her for the handle of the door. The other man is holding something out of his window, and as she goes on retreating, the first man takes it and walks towards her. ‘Je suis en retard,’ she says in her unsteady French, her tongue fumbling over the words. ‘I am late for an appointment.’ Then she sees what he is holding: a piece of card, half a picture – windows, roses, a pitched roof. ‘This is yours, Mrs Last.’

She goes on opening the car door. She reaches for her purse and looks inside it. ‘Please take a look,’ he is saying, and she finds what she is looking for, folded within her black wallet. The matching half. She takes it out and holds it towards him, and he comes forward holding his half and they stand rather close as they put them clumsily join to join, a picture made whole again, a house in the sunshine.

‘Your husband gave it to my friend,’ he says.

‘Yes.’

All the questions that Laura might ask run through her mind and are lost for the moment. She leans against the warm car, and feels her heart slowing from its panic, and over the woods below her she sees an eagle hovering in the warm winds, its huge wingspan in profile, so slow that it is still, suspended.