Полная версия

At the Close of Play

To be honest it all became a bit overwhelming when I retired from Test cricket and I wish I could have had her sense of acceptance. Admitting to myself that I was no longer up to it, saying the words out loud to Rianna and then the team and then telling the world; wandering out to bat for that last time and seeing the South Africans lined up in a guard of honour as I approached the WACA pitch … all the other little things that happened for the last time ever in the few weeks leading up to that moment had been like a series of small deaths.

I only ever wanted to play cricket and I could never bring myself to imagine a time when I wasn’t playing the game, but that time is approaching.

Since leaving the Test team I have been like a salmon (Tasmanian, of course) swimming back upstream to where it all started. Before I put this old kit bag away for the last time I had some unfinished business. Cricket swept me up early. One day I didn’t know how to get on a plane and then for a long time after I wondered if I would ever get off one.

International cricket expanded to fill every available space in my life. At the academy I had been able to get home occasionally, but after that visits got rarer until there was barely time to swing by and have a hit of golf with the old man, or a cup of instant coffee with Mum at the breakfast bar. My little brother, Drew, and sister, Renee — my whole family I guess — watched me on television and tracked my progress that way. I suppose all of Australia did and a few other nations as well. I was away when my pa died and will never forget the helplessness as I spoke to Dad on the phone from England. I wasn’t there for him when he needed me.

I’m fiercely loyal. I’m proud of my background and the values I was taught in this town and these dressing rooms. No matter how many five-star hotels I’ve slept in, how many first-class flights I’ve been on, how many politicians and businessmen and celebrities have swept through my life I have never lost the sense that I’m that small-town boy who didn’t have much but wanted for nothing.

So, in what’s left of this last summer of my cricket life, I am trying to catch up.

It’s all rushed as it always is. I trained in Hobart yesterday, drove up to Launceston last night and will head back to Hobart first thing tomorrow. I’m so early for the game I park the car down the road a bit and call Rianna on the phone, even when I’ve done that I’m still the first there so I open the clubrooms and find a space where I figure nobody else will be, just as I did when I was a boy. It’s best to stay out of the way and not be noticed, although that’s impossible today.

It’s early February and the Mowbray Eagles are playing Launceston on the parkland by the Esk River, next to the footy ground.

There’re hundreds at the ground and they line up for autographs and I sign them all when I get a chance. There’s a lot of familiar faces, people from my past introducing me to their kids. My mum and dad are playing golf because it’s a Saturday and that’s what they do and I love them for that. They’re set in their ways but I have never for one moment felt they haven’t been with me every innings I’ve played. They’re locals and they like their lives down here. They don’t like their routine disrupted so they haven’t seen me play that much. They would never think of going overseas to watch a game of cricket. It was hard enough getting them to Perth for my last match. No, there’s a golf course down the road and every Saturday Mum and Dad have a date that starts at the first hole.

I STRAP ON MY PADS and make my way out to the middle. Head down at first, trying to block out the crowd like I do whether I’m at the MCG, in Mumbai or at Mowbray. Hitting the grass I try and get a little feeling in the legs, running on the spot a bit. I make it to the middle and take centre, just as I learned all those years back, and I scratch my studs into the surface of the wicket. Marking out my territory again.

I do it really tough. Cricket is such a great leveller. I last an hour, but it’s as hard an hour as I’ve spent at the crease. The council owns the ground and keeps the grass long and it’s impossible to hit a boundary along the ground. It’s been raining and the wicket is seaming. Finally I shoulder arms to a ball that cuts back a foot or two and takes my off-stump.

This game rarely lets you get ahead of yourself. In the evening we have a few beers in the rooms with our gear all around us and the chat begins all over again.

This is who I am and now this is finishing and I suppose that begs a question I am not too keen to ponder: I might not have been finished with the game, but it was finished with me and am I now the person it has shaped?

Someone said when I walked out of the Australian dressing room the door slammed on a generation of cricket. That might be right, but for me there was something deeper. I had been raised in the game. The dressing room was a cradle, I was formed in these confines, I grew up in them and I have as good as lived in them for all my adult life up to this point. There was only ever the game and the team, the competition and the anticipation, and now it is time to move on.

AFTER MOWBRAY it was back to Sheffield Shield.

Twenty years ago I played my first game for Tassie as a 17-year-old and here I am again. At 38 I get to celebrate for the first time as my home state wins the coveted Sheffield Shield. It’s a great feeling and I’ve had a good year, even knocking up a 200 in the game against NSW that followed my Mowbray visit.

Cricket is a cruel mistress and there she was at me again. I had started the summer in great form in first-class cricket and was the highest run-scorer going into the series against South Africa that would be my last. I felt like my technique, my reflexes, my game were in the best place they had ever been, but when it came time to wear the baggy green I could not make a run. So, going out and hitting a double hundred in the Shield a few months after I had literally landed on my face in Test cricket was a bitter irony, but a sure indication that there’s an enormous mental element to this game. No matter how hard I tried — and believe me there is nobody who tries and trains harder than me — I couldn’t put all the pieces back together at Test level.

It still hurts to admit I had lost it, but it felt good to end the season giving back to my home state, a place that had given so much but for most of my career had been so far away, so hard to get back to.

While Tasmania was winning the Shield competition Australian cricket seemed to be spiralling out of control during a series against India.

They’d barely missed a beat after I left. In my last game in Perth we had a chance to regain the number one rank in world cricket, but now that seemed so far away. In the first series they played after my retirement they easily accounted for a Sri Lankan side. My only contribution was a lap of honour at Bellerive before the Test.

After that things just seemed to go wrong and it was hard to watch. I know more than most how India can get on top of you. The cricket is like the country — it can be breathtaking, but at times it can close in on you and you feel like you are being smothered. It’s easy to lose your way there and the Aussies did. I had never led a team to a series victory in India, but not only did they lose 4–0 on the field, they lost their way off it. The dressing room that I loved had changed in the past few years and as hard as it was to see how bad they were going out in the middle, it was just as hard knowing how much they were struggling off it.

I’d seen the signs. When we lost in Perth I went with the boys to have a drink with the South Africans and I was taken aback by the feeling they had in the sheds. Sure, it’s easy to be happy when you’ve won so well, but they were a tight group, a small travelling band that had gelled together and taken down the enemy and as I looked at them enjoying the afterglow I was gripped with a sense of loss.

We used to be like that, I thought.

Everything has to change in cricket, but I’m not so convinced that all the changes I’ve seen in the past few years are for the better. I was in that Australian dressing room for 20 years and it seemed every time a legend left his corner another arrived to take that place. I saw Adam Gilchrist replace Ian Healy, and Stuart MacGill pick up a lazy 200 wickets when forced to play understudy to Shane Warne. I remember when a 30-year-old called Michael Hussey first got his shot at the big time and a young bloke called Michael Clarke came into the side.

Michael Clarke’s got the captaincy now and it’s fair to say that the trend that started in the last years of my time in the job has continued. First-class cricket just isn’t bringing up the players, particularly batsmen, it once did. There was a time when guys with 10,000 first-class runs, guys who had scored century after century all around Australia and in England for counties, could not get a look-in. Sure there were a few, myself included, who came in young and relatively inexperienced, but we knew we were always under pressure for our places from others who had equal rights to them.

Anyway, I have to let that go now …

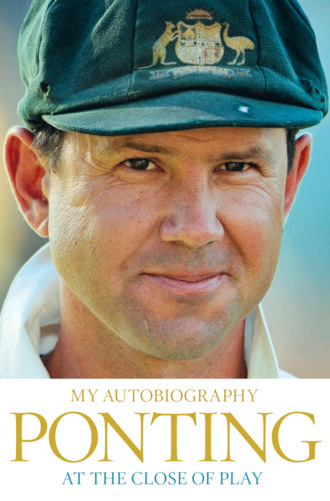

The baggy green cap is the most powerful symbol in Australian sport. Nothing comes close to it for its tradition, meaning and representation. Only a small number of cricketers have played Test cricket for Australia and been presented with the baggy green. 365 cricketers achieved that honour before I made my Test debut in 1995. My Test cap number 366 is now almost part of my DNA.

Fewer than 450 cricketers have earned a baggy green since Test cricket began in 1877. That’s quite phenomenal when you think how many Australians have dedicated their life to cricket but have never reached the level of playing Test cricket for Australia. This is what I’ve always talked about when presenting brand-new baggy green caps to players making their debut for Australia. You are joining a pretty elite group and have achieved a pinnacle of personal achievement in Australian cricket. You are now part of the baggy green family — an exclusive club. How lucky are we!

During my career, I had two baggy greens. My original cap was stolen out of my luggage on the way home from Sri Lanka in 1999. I’d only played 24 Tests at the time and I was gutted to think that the cap was gone. I was given a replacement baggy green that would stay with me right through to my last Test in Perth in 2012. It was a constant companion on and off the field. After losing my first cap, I carried my baggy green in my hand luggage wherever I went. It was with me in 144 Test matches all over the world and was looking pretty worse for wear when I retired from international cricket. There had been calls for me to change to a brand-new baggy green. Some said I was not treating the cap with the respect it demands, by wearing a faded, torn and out of shape baggy green on which you could hardly identify the Australian coat of arms on the front. But I am traditionalist and my baggy green tells a story — the story of my career. It reflects where I was, where I went and, in the latter years, how it was on its last legs — just like me. To me, my baggy green was a symbol of national pride, a monument to all my predecessors, team-mates and future Australian Test players, and a trophy for all the successes we achieved together. That baggy green was me.

Now it forms part of a very special presentation box that Rianna and the girls gave to me for my first Christmas as a retired international cricketer. It sits beside a brand-new baggy green with the most beautiful images of our family standing on the WACA after my last game. The new baggy green now symbolises the next stage of my life. A time of looking forward while never forgetting the incredible opportunities that 168 Test matches, with my baggy green, gave me.

MY NAME IS Ricky Thomas Ponting and I played cricket.

I played junior cricket, indoor cricket, club cricket, rep cricket, state cricket, T20 cricket, one-day cricket and Test cricket. When I didn’t play cricket, I trained to play cricket. I played cricket almost everywhere cricket is played and with some of the greatest players there have ever been. I played in what might have been the best team the world has ever seen. I tried to be the best cricketer I could possibly be. I gave everything I had to that cause from the time I was a small boy until long after most of my contemporaries had walked away.

I was born in Launceston, Tasmania, a small town on a small island state that often gets left off the map of Australia. We’re proud people who look after ourselves and who figure Hobart is the big smoke and the mainland is another country.

My early years were spent in the suburbs of Prospect and then Newnham, where we lived with my grandparents. When we could afford it, we moved to the housing estate at Rocherlea. I played cricket at school and then for the Mowbray Eagles, just like my dad and just like my Uncle Greg who was Mum’s brother. People identify me with Mowbray and that’s all right with me because that is where I learned the game.

I was born on December 19, 1974 to Graeme and Lorraine Ponting. My mum reckons I was a ‘beautiful baby’ but she might be biased. ‘No trouble at all,’ she tells me. ‘Slept and ate, that’s all you did.’ One of her most prominent early memories of me is when I was sitting on the lounge-room floor, eyes fixed on the television, watching Kim Hughes bat. Kim was my first hero in Test cricket, a batsman who, when he was on, was unstoppable. I remember him taking on the West Indies at the MCG the week after my seventh birthday, their fast bowlers aiming at his chest and head, him hooking and pulling fearlessly. That knock stays burned in my memory and probably set the standard for the sort of cricketer I wanted to become. Australian cricket wasn’t going so well then, but he stood up that day and scored 100 out of an innings total of 194. Holding, Roberts, Garner and Croft threw everything they had at him, but he was undefeated at the end of the innings and the Australians went on to win that match. That didn’t happen all that often back then. There was no doubt in my mind, even then, that I wanted to be out there doing exactly the same.

One of Dad’s early recollections of me is not as flattering as Mum’s. ‘When you were three, you used to wait out the front for the children walking home from school, and you’d run out and kick them and then run back inside,’ he once told me. It was, he reckons, one of the first signs of my ‘mischievous’ streak. I’d like to think it showed I was never going to be intimidated by anyone older or bigger and for the next 20 years of my life I always seemed to be the youngest person in the room. I was the boy in the men’s team, the 16-year-old at the cricket academy with Warnie who already had his own car and his own ways, the kid who was missing the final years at school to play first-class cricket, the 20-year-old walking onto the WACA to make my debut in Mark Taylor’s team. Fortunately by then I’d stopped kicking the big kids in the leg …

I have a younger brother, Drew, and a sister, Renee, who is younger again. Today they both live within a couple of minutes of our parents’ place. I’m the only one that went away.

Mum also has strong memories of me always being outside playing cricket as a boy. ‘You always had to be the batsman and Drew had to bowl or field,’ she says. ‘You’d bat for an hour before Drew would get a bat. Then Drew would finally have a go, but he’d only last two minutes and you’d go back in.’ My little brother was the first to suffer for my love. Most batsmen value their wicket, none like getting out, but I took it to an extreme and it all started in the backyard.

Like all kids we built the rules of cricket around the circumstances of our backyard. Over the fence was out and God help you if the old man caught you wading into his prized vegetable patch to fetch a ball. He loved that garden and it lay in wait from point to long-on, ready to swallow a ball. Drew reckons I mastered the art of hitting the ball over the garden and into the fence. I never let him bat for too long because it seemed part of the natural order of things that I was there doing what my hero, Kim Hughes, had done, although with all due respect to Drew he was no Michael Holding. I’d knock him over with my bowling as quick as I could and then take guard again. I have to admit Drew’s ability to bowl endless overs was important to my development and I must thank him some time.

As a kid, growing up, I looked upon Mowbray as being a flash part of town.

We didn’t come from the wrong side of the tracks so much as the wrong side of the river. Launceston is divided by the Tamar river, one side was middle class and nice and the other was where we lived. On our side they had the railway workshops, the factories and all the key landmarks of my early life — at the centre of which was the cricket club. In the Mowbray dressing rooms on a Saturday night they used to tell beery yarns about having to fight to cross the bridge into town, they weren’t true but they told you a little bit about the ‘us and them’ nature of where I came from. Our greatest rivals were Riverside; they came from the nice part of town and sometimes complained that we played cricket too hard. It was a complaint I would hear on and off for a lot of my career, but I never heard them say we weren’t playing fair or honestly.

My father was born in Pioneer, a mining village in the north-eastern tip of the island. His father, Charlie, was a tin miner who wanted a better life for his family so he worked two jobs, digging tin from the ground all week and then travelling to Launceston to dig foundations for houses on the weekends. With the money he made they moved to Newnham. They were people who knew a different life. Dad would tell stories about trapping rabbits and the like so they could eat, and I reckon that his enormous vegetable garden had something to do with that poor background.

The Pontings had arrived in Tasmania back in about 1890. My great great grandfather was a miner, his son was a miner and so was his son, my grandfather Charlie, but Charlie joined the RAAF when the war broke out and that might have changed things. He married Connie, my grandmother, during the war and sometime later they moved from Pioneer into Launceston and that was the last time our family dug for tin.

Pop kept greyhounds and Dad tells the story that he went to the races one night and an owner said to him, ‘You want a dog? I’ve got one that’s no good to me, it can’t win a race.’ Dad walked five kilometres home with the dog and put it under the house. Fed it some steak. His father said he couldn’t keep it, but when Dad came home the next day his father had built a run across the back garden and it all started from there. The dog won its first race and we were away. Or that’s how the story goes.

In Rocherlea Mum and Dad rented a small three-bedroom housing commission home on the bend at 22 Ti Tree Crescent. It was a cottage that had a nice front yard and a reasonable backyard dominated by Dad’s vegetable garden. We were on the edge of town. It wasn’t the best neighbourhood and always had a bad reputation — there were some houses that seemed to be visited by the police on a regular basis and I suppose there was a bit of trouble around but I avoided it. I can’t ever remember our house being locked, which tells you a little bit about how life was.

We didn’t have much money when I was growing up, but I never remember us wanting for anything. Dad left school early to pursue a life as a golf professional, which didn’t work out. He was a great sportsman and I think the interest he took in my life was because he wanted me to have a chance to do the things he didn’t. Dad was a good cricketer and footballer and a better golfer; I suppose you could say he was pushy, but that’s probably too simplistic. Dad saw I was good and did the right thing by letting me know when I could be better. I always wanted to make him proud and never resented the way he encouraged me. He worked at the railways and other jobs, eventually finding his place as a groundsman. He didn’t earn a lot but he loved — loves — the work. Mum and Dad’s life revolved around us kids. Mum worked, but always made sure she or Dad was there for us when we were home. She was raised in Invermay and for most of our early lives she worked at the local petrol station there.

I sometimes think that if I hadn’t dragged them to the odd game of cricket in the past 30 years that they might never have left Launceston.

From our house in Rocherlea, it was about two kilometres south to Mowbray Golf Club, a bit less than a kilometre further to the racecourse, and another kilometre closer to the city centre to get to Invermay Park, the former swampland that would become the home ground of the Mowbray Cricket Club in the late 1980s. That reclaimed land is why people from around this area have long been known as ‘Swampies’.

I am extremely fortunate to have parents who love their sport. My mum represented Tassie at vigoro (a game not too dissimilar to cricket), played competitive badminton and netball, and later in life started playing golf because, as she explains it, her husband was always down at the clubhouse. Taking up the game was her best chance of seeing more of him.

Mum and Dad wanted their kids to be happy, humble, brave and honest. There was a toughness about where I was growing up and my parents never hid me from that, but neither did they use it as an excuse to let me run wild. I was sort of street-smart, and that and a combination of my parents’ love for me and my addiction to all things sport kept me out of serious trouble. There was, though, a bit of rascal in my make-up. One evening I came home late, explaining that I’d been at a mate’s place doing schoolwork, which was in itself a long bow. Worse, my shoes were covered in mud from the creeks at Mowbray Golf Club, where we’d been searching for lost balls that we could sell back to the members. I’ll never forget how Dad belted me as he demanded that in future I tell the truth, and how the message sank in. At the same time, I couldn’t believe how stupid I’d been, not cleaning my shoes before I got home.

Honesty was important to Dad and he passed that on.

I was never top of my class academically, but neither was I near the bottom. In Rocherlea, learning to stay out of trouble was as important as learning your times tables. Some might be surprised to learn I was a prefect for two of the years I was at high school. I suppose that shows that even at an early age I showed some hints that there was some leadership capabilities somewhere deep inside this sport-obsessed kid.

Sport was the making of me. From a very early age I knew I could hold my own at cricket or football, which gave me plenty of confidence and a lot of street cred with boys bigger and older than me. Because of the rules governing school sport in Tasmania at the time I didn’t play any organised cricket or football until grade five at Mowbray Heights Primary School, when I was 10, and I didn’t make my debut in senior Saturday afternoon cricket with the men at Mowbray until 1987, when I was 12. Before then, though, I did take part in some school-holiday coaching clinics, watched the Mowbray A-Grade team play and won a thousand imaginary Test matches against my little brother and whoever else we could recruit into neighbourhood contests.

There were other kids who might have had more material possessions, but living on the edge of town meant we had plenty of open space and in the days before laptops and the like we used it well. It could get icy in winter, but it’s never too cold to kick a footy, and Dad found me a set of clubs when I wanted to hit a golf ball. If Drew and I could get down for a round of golf Mum would pack us a flask of cordial and give us enough money for a pack of chips and we were away. There was always cricket gear around the house and when a group of us went down to the local nets or park we always practised with a fair-dinkum cricket ball.