Полная версия

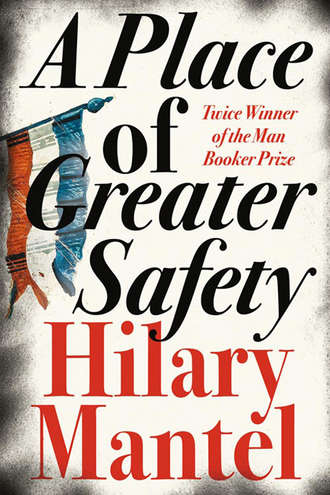

A Place of Greater Safety

WHEN M. DE VIEFVILLE arrived home, he would make his way through the narrow huddle of small-town streets, and through the narrow huddle of provincial hearts; and he would bring himself to call on Jean-Nicolas, in his tall white book-filled house on the Place des Armes. Maître Desmoulins had an obsession nowadays, and de Viefville dreaded meeting him, meeting his baffled eyes and being asked once again the question that no one could answer: what had happened to the good and beautiful child he had sent to Cateau-Cambrésis nine years earlier?

On Camille’s sixteenth birthday, his father was stamping about the house. ‘I sometimes think,’ he said, ‘that I have got on my hands a depraved little monster with no feelings and no sense.’ He has written to the priests in Paris, to ask what they teach his son; to ask why he looks so untidy, and why during his last visit home he has seduced the daughter of a town councillor, ‘a man,’ he says, ‘whom I see every day of my working life’.

Jean-Nicolas did not really expect answers to these questions. His real objections to his son were rather different. Why, he really wanted to know, was his son so emotional? Where did he get this capacity to infect others with emotion: to agitate them, discomfit them, shake them out of their ease? Ordinary conversations, in Camille’s presence, went off at peculiar tangents, or turned into blazing rows. Safe social conventions took on an air of danger. You couldn’t, Desmoulins thought, leave him alone with anybody.

It was no longer said that his son was a little Godard. Neither did the de Viefvilles rush to claim him. His brothers were thriving, his sisters blooming, but when Camille slipped in at the front door of the Old House, he looked as if he had come on a message from the Foundling Hospital.

Perhaps, when he is grown up, he will be one of those boys who you pay to stay away from home.

THERE ARE SOME noblemen in France who have discovered that their best friends are their lawyers. Now that revenue from land is falling steadily, and prices are rising, the poor are getting poorer and the rich are getting poorer too. It has become necessary to assert certain privileges that have been allowed to lapse over the years. Often, dues to which one is entitled have not been paid for a generation; that lax and charitable lordship must now cease. Again, one’s ancestors have allowed part of their estates to become known as ‘common land’ – an expression for which there is usually no legal foundation.

These were the golden days of Jean-Nicolas; if, privately, he had worries, at least professionally he was prospering. Maître Desmoulins was no bootlicker – he had a lively sense of his own dignity, and was moreover a liberal-minded man, an advocate of reform in most spheres of national life. He read Diderot after dinner, and subscribed to the Geneva reprint of the Encyclopédie, which he took in instalments. Nevertheless, he found himself much occupied with registers of rights and tracing of titles. A couple of old strongboxes were brought around and trundled up to his study, and when they were opened a faint musty smell crept out. Camille said, ‘So that is what tyranny smells like.’ His father swept his own work aside and delved into the boxes; very tenderly he held the old yellow papers up to the light. Clément, the youngest, thought he was looking for buried treasure.

The Prince de Condé, the district’s premier nobleman, called personally on Maître Desmoulins in the tall, white, book-filled, very very humble house on the Place des Armes. Normally he would have sent his land agent, but he was piqued by curiosity to know the man who was doing such good work for him. Besides, if honoured by a visit, the fellow would never dare to send in a bill.

It was late afternoon, autumn. Warming in his hand a glass of deep red wine, and mellow, aware of his condescension, the Prince lounged in a wash of candlelight; evening crept up around them, and painted shadows in the corners of the room.

‘What do you people want?’ he asked.

‘Well …’ Maître Desmoulins considered this large question. ‘People like me, men of the professional classes, we would like a little more say, I suppose – or let me put it this way, we would welcome the opportunity to serve.’ It is a fair point, he thinks; under the old King, noblemen were never ministers, but, increasingly, all the ministers are noblemen. ‘Civil equality,’ he said. ‘Fiscal equality.’

Condé raised his eyebrows. ‘You want the nobility to pay your taxes for you?’

‘No, Monseigneur, we want you to pay your own.’

‘I do pay tax,’ Condé said. ‘I pay my poll tax, don’t I? All this property-tax business is nonsense. And so, what else?’

Desmoulins made a gesture, which he hoped was eloquent. ‘An equal chance. That’s all. An equal chance at promotion in the army or the church …’ I’m explaining it as simply as I can, he thought: an ABC of aspiration.

‘An equal chance? It seems against nature.’

‘Other nations conduct themselves differently. Look at England. You can’t say it’s a human trait, to be oppressed.’

‘Oppressed? Is that what you think you are?’

‘I feel it; and if I feel it, how much more do the poor feel it?’

‘The poor feel nothing,’ the Prince said. ‘Do not be sentimental. They are not interested in the art of government. They only regard their stomachs.’

‘Even regarding just their stomachs –’

‘And you,’ Condé said, ‘are not interested in the poor – oh, except as they furnish you with arguments. You lawyers only want concessions for yourselves.’

‘It isn’t a question of concessions. It’s a question of human beings’ natural rights.’

‘Fine phrases. You use them very freely to me.’

‘Free thought, free speech – is that too much to ask?’

‘It’s a bloody great deal to ask, and you know it,’ Condé said glumly. ‘The pity of it is, I hear such stuff from my peers. Elegant ideas for a social re-ordering. Pleasing plans for a “community of reason”. And Louis is weak. Let him give an inch, and some Cromwell will appear. It’ll end in revolution. And that’ll be no tea-party.’

‘But surely not?’ Jean-Nicolas said. A slight movement from the shadows caught his attention. ‘Good heavens,’ he said, ‘what are you doing there?’

‘Eavesdropping,’ Camille said. ‘Well, you could have looked and seen that I was here.’

Maître Desmoulins turned red. ‘My son,’ he said. The Prince nodded. Camille edged into the candlelight. ‘Well,’ said the Prince, ‘have you learned something?’ It was clear from his tone that he took Camille for younger than he was. ‘How did you manage to keep still for so long?’

‘Perhaps you froze my blood,’ Camille said. He looked the Prince up and down, like a hangman taking his measurements. ‘Of course there will be a revolution,’ he said. ‘You are making a nation of Cromwells. But we can go beyond Cromwell, I hope. In fifteen years you tyrants and parasites will be gone. We shall have set up a republic, on the purest Roman model.’

‘He goes to school in Paris,’ Jean-Nicolas said wretchedly. ‘He has these ideas.’

‘And I suppose he thinks he is too young to be made to regret them,’ Condé said. He turned on the child. ‘Whatever is this?’

‘The climax of your visit, Monseigneur. You want to take a trip to see how your educated serfs live, and amuse yourself by trading platitudes with them.’ He began to shake – visibly, distressingly. ‘I detest you,’ he said.

‘I cannot stay to be abused,’ Condé muttered. ‘Desmoulins, keep this son of yours out of my way.’ He looked for somewhere to put his glass, and ended by thrusting it into his host’s hand. Maître Desmoulins followed him on to the stairs.

‘Monseigneur –’

‘I was wrong to condescend. I should have sent my agent.’

‘I am so sorry.’

‘No need to speak of it. I could not possibly be offended. It is not in me.’

‘May I continue your work?’

‘You may continue my work.’

‘You are really not offended?’

‘It would be ungracious of me to be offended at what cannot possibly be of any account.’

By the front door, his small entourage had quickly assembled. He looked back at Jean-Nicolas. ‘I say out of my way and I mean well out of my way.’

When the Prince had driven away, Jean-Nicolas mounted the stairs and re-entered his office. ‘Well, Camille?’ he said. A perverse calm had entered his voice, and he breathed deeply. The silence prolonged itself. The last of the light had faded now; a crescent moon hung in pale inquiry over the square. Camille had retired into the shadows again, as if he felt safer there.

‘That was a very stupid, fatuous conversation you were having,’ he said in the end. ‘Everybody knows those things. He isn’t mentally defective. They’re not: not all of them.’

‘Do you tell me? I live so out of society.’

‘I liked his phrase, “this son of yours”. As if it were eccentric of you, to have me.’

‘Perhaps it is,’ Jean-Nicolas said. ‘Were I a citizen of the ancient world, I should have taken one look at you and popped you out on some hillside, to prosper as best you might.’

‘Perhaps some passing she-wolf might have liked me,’ Camille said.

‘Camille – when you were talking to the Prince, you somehow lost your stutter.’

‘Mm. Don’t worry. It’s back.’

‘I thought he was going to hit you.’

‘Yes, so did I.’

‘I wish he had. If you go on like this,’ said Jean-Nicolas, ‘my heart will stop,’ he snapped his fingers, ‘like that.’

‘Oh, no,’ Camille smiled. ‘You’re quite strong really. Your only affliction is kidney-stones, the doctor said so.’

Jean-Nicolas had an urge to throw his arms around his child. It was an unreasonable impulse, quickly stifled.

‘You have caused offence,’ he said. ‘You have prejudiced our future. The worst thing about it was how you looked him up and down. The way you didn’t speak.’

‘Yes,’ Camille said remotely. ‘I’m good at dumb insolence. I practise: for obvious reasons.’ He sat down now in his father’s chair, composing himself for further dialogue, slowly pushing his hair out of his eyes.

Jean-Nicolas is conscious of himself as a man of icy dignity, an almost unapproachable stiffness and rectitude. He would like to scream and smash the windows: to jump out of them and die quickly in the street.

THE PRINCE WILL SOON forget all this in his hurry to get back to Versailles.

Just now, faro is the craze. The King forbids it because the losses are so high. But the King is a man of regular habits, who retires early, and when he goes the stakes are raised at the Queen’s table.

‘The poor man,’ she calls him.

The Queen is the leader of fashion. Her dresses – about 150 each year – are made by Rose Bertin, an expensive but necessary modiste with premises on the rue Saint-Honoré. Court dress is a sort of portable prison, with its bones, its vast hoops, its trains, its stiff brocades and armoured trimmings. Hairdressing and millinery are curiously fused, and vulnerable to the caprice du moment; George Washington’s troops, in battle order, sway in pomaded towers, and English-style informal gardens are set into matted locks. True, the Queen would like to break away from all this, institute an age of liberty: of the finest gauzes, the softest muslins, of simple ribbons and floating shifts. It is astonishing to find that simplicity, when conceived in exquisite taste, costs just as much as the velvets and satins ever did. The Queen adores, she says, all that is natural – in dress, in etiquette. What she adores even more are diamonds; her dealings with the Paris firm of Böhmer and Bassenge are the cause of widespread and damaging scandal. In her apartments she throws out furniture, tears down hangings, orders new – then moves elsewhere.

‘I am terrified of being bored,’ she says.

She has no child. Pamphlets distributed all over Paris accuse her of promiscuous relations with her male courtiers, of lesbian acts with her female favourites. In 1776, when she appears in her box at the Opéra, she is met by hostile silences. She does not understand this. It is said that she cries behind her bedroom doors: ‘What have I done to them? What have I done?’ Is it fair, she asks herself, if so much is really wrong, to harp on one woman’s trivial pleasures?

Her brother the Emperor writes from Vienna: ‘In the long run, things cannot go on as they are … The revolution will be a cruel one, and may be of your own making.’

IN 1778 VOLTAIRE returned to Paris, eighty-four years old, cadaverous and spitting blood. He traversed the city in a blue carriage covered with gold stars. The streets were lined with hysterical crowds chanting ‘Vive Voltaire.’ The old man remarked, ‘There would be just as many to see me executed.’ The Academy turned out to greet him: Franklin came, Diderot came. During the performance of his tragedy Irène the actors crowned his statue with laurel wreaths and the packed galleries rose to their feet and howled their delight and adoration.

In May, he died. Paris refused him a Christian burial, and it was feared that his enemies might desecrate his remains. So the corpse was taken from the city by night, propped upright in a coach: under a full moon, and looking alive.

A MAN CALLED NECKER, a Protestant, Swiss millionaire banker, was called to be Minister of Finance and Master of Miracles to the court. Necker alone could keep the ship of state afloat. The secret, he said, was to borrow. Higher taxation and cuts in expenditure showed Europe that you were on your knees. But if you borrowed you showed that you were forward-looking, go-getting, energetic; by demonstrating confidence, you created it. The more you borrowed, the more the effect was achieved. M. Necker was an optimist.

It even seemed to work. When, in May 1781, the usual reactionary, anti-Protestant cabal brought the minister down, the country felt nostalgia for a lost, prosperous age. But the King was relieved, and bought Antoinette some diamonds to celebrate.

Georges-Jacques Danton had already decided to go to Paris.

It had been so difficult to get away, initially; as if, Anne-Madeleine said, you were going to America, or the moon. First there had been the family councils, all the uncles calling with some ceremony to put their points of view. They had dropped the priest business. For a year or two he had been around the little law offices of his uncles and their friends. It was a modest family tradition. Nevertheless. If he was sure it was what he wanted …

His mother would miss him; but they had grown apart. She was a woman of no education, with an outlook that she had deliberately narrowed. The only industry of Arcis-sur-Aube was the manufacture of nightcaps; how could he explain to her that the fact had come to seem a personal affront?

In Paris he would receive a modest clerk’s allowance from the barrister in whose chambers he would study; later, he would need money to establish himself in practice. His stepfather’s inventions had eaten into the family money; his new weaving loom was especially disaster prone. Bemused by the clatter and the creak of the dancing shuttles, they stood in the barn and stared at his little machine, waiting for the thread to break again. There was a bit of money from M. Danton, dead these eighteen years, which had been set aside for when his son grew up. ‘You’ll need it for the inventions,’ Georges-Jacques said. ‘I’ll feel happier, really, to think I’m making a fresh start.’

That summer he visited the family. A pushy and energetic boy who went to Paris would never come back – except for visits, perhaps, as a distant and successful man. So it was proper to make these calls, to leave out no one, no distant cousin or great-uncle’s widow. In their cool, very similar farmhouses he had to stretch out his legs and outline to them what he wanted in life, to submit his plans to their good understanding. He spent long afternoons in the parlours of these widows and maiden aunts, with old ladies nodding in the attenuated sunlight, while the dust swirled purplish and haloed their bent heads. He was never at a loss for something to say to them; he was not that sort of person. But with each visit he felt that he was travelling, further and further away.

Then there was just one visit left: Marie-Cécile in her convent. He followed the straight back of the Mistress of Novices down a corridor of deathly quiet; he felt absurdly large, too much a man, doomed to apologise for himself. Nuns passed in a swish of dark garments, their eyes on the ground, their hands hidden in their sleeves. He had not wanted his sister to come here. I’d rather be dead, he thought, than be a woman.

The nun halted, gestured him through a door. ‘It is an inconvenience,’ she said, ‘that our parlour is so far within the building. We will have one built near the gate, when we get the funds.’

‘I thought your house was rich, Sister.’

‘Then you are misinformed.’ She sniffed. ‘Some of our postulants bring dowries that are barely sufficient to buy the cloth for their habits.’

Marie-Cécile was seated behind a grille. He could not touch or kiss her. She looked pale; either that, or the harsh white of the novice’s veil did not suit her. Her blue eyes were small and steady, very like his own.

They talked, found themselves shy and constrained. He told her the family news, explained his plans. ‘Will you come back,’ she asked, ‘for my clothing ceremony, for when I take my final vows?’

‘Yes,’ he said, lying. ‘If I can.’

‘Paris is a very big place. Won’t you be lonely?’

‘I doubt it.’

She looked at him earnestly. ‘What do you want out of life?’

‘To get on in it.’

‘What does that mean?’

‘I suppose it means I want to get a position, to have money, to make people respect me. I’m sorry, I see no point in being mealy-mouthed about it. I just want to be somebody.’

‘Everybody’s somebody. In God’s sight.’

‘This life has turned you pious.’

They laughed. Then: ‘Have you any thought for the salvation of your soul, in the plans you’ve made?’

‘Why should I have to think about my soul, when I’ve a great lazy sister a nun, with nothing to do but pray for me all day?’ He looked up. ‘What about you, are you – you know – happy?’

She sighed. ‘Think of the economics of it, Georges-Jacques. It costs money to marry. There are too many girls in our family. I think the others volunteered me, in a way. But now that I’m here – yes, I’m settled. It really does have its consolations, though I wouldn’t expect you to acknowledge them. I don’t think you, Georges-Jacques, were born for the calmer walks of life.’

He knew that there were farmers in the district who would have taken her for the meagre dowry she had brought to the convent, and who would have been glad of a wife of robust health and cheerful character. It would not have been impossible to find a man who would work hard and treat her decently, and give her some children. He thought all women ought to have children.

‘Could you still get out?’ he asked. ‘If I made money I could look after you, we could find you a husband or you could do without, I’d take care of you.’

She held up a hand. ‘I said, didn’t I – I’m happy. I’m content.’

‘It saddens me,’ he said gently, ‘to see that the colour has gone from your cheeks.’

She looked away. ‘Better go, before you make me sad. I often think, you know, of all the days we had in the fields. Well, that is over now. God keep you.’

‘And God keep you.’

You rely on it, he thought; I shan’t.

III. At Maître Vinot’s

(1780)

SIR FRANCIS BURDETT, British Ambassador, on Paris: ‘It is the most ill-contrived, ill-built, dirty stinking town that can possibly be imagined; as for the inhabitants, they are ten times more nasty than the inhabitants of Edinburgh.’

GEORGES-JACQUES came off the coach at the Cour des Messageries. The journey had been unexpectedly lively. There was a girl on board, Françoise-Julie; Françoise-Julie Duhauttoir, from Troyes. They hadn’t met before – he’d have recalled it – but he knew something of her; she was the kind of girl who made his sisters purse their lips. Naturally: she was good-looking, she was lively, she had money, no parents and spent six months of the year in Paris. On the road she amused him with imitations of her aunts: ‘Youth-doesn’t-last-for-ever, a-good-reputation-is-money-in-the-bank, don’t-you-think-it’s-time-you-settled-down-in-Troyes-where-all-your-relatives-are-and-found-yourself-a-husband-before-you-fall-apart?’ As if, Françoise-Julie said, there were going to be some sudden shortage of men.

He couldn’t see there ever would be, for a girl like her. She flirted with him as if he were just anybody; she didn’t seem to mind about the scar. She was like someone who has been gagged for months, let out of a gaol. Words tumbled out of her, as she tried to explain the city, tell him about her life, tell him about her friends. When the coach came to a halt she did not wait for him to help her down; she jumped.

The noise hit him at once. Two of the men who had come to see to the horses began to quarrel. That was the first thing he heard, a vicious stream of obscenity in the hard accent of the capital.

Her bags around her feet, Françoise-Julie stood and clung to his arm. She laughed, with sheer delight at being back. ‘What I like,’ she said, ‘is that it’s always changing. They’re always tearing something down and building something else.’

She had scrawled her address on a sheet of paper, tucked it into his pocket. ‘Can’t I help you?’ he said. ‘See you get to your apartment all right?’

‘Look, you take care of yourself,’ she said. ‘I live here, I’ll be fine.’ She spun away, gave some directions about her luggage, disbursed some coins. ‘Now, you know where you’re going, don’t you? I’ll expect to see you within a week. If you don’t turn up I’ll come hunting for you.’ She picked up her smallest bag; quite suddenly, she lunged at him, stretched up, planted a kiss on his cheek. Then she whirled away into the crowd.

He had brought only one valise, heavy with books. He hoisted it up, then put it down again while he fished in his pocket for the piece of paper in his stepfather’s handwriting:

The Black Horse

rue Geoffroy l’Asnier,

parish of Saint-Gervais.

All about him, church bells had begun to ring. He swore to himself. How many bells were there in this city, and how in the name of God was he to distinguish the bell of Saint-Gervais and its parish? He screwed the paper up and dropped it.

Half the passers-by were lost. You could tramp for ever in the alleyways and back courts; there were streets with no name, there were building sites strewn with rubble, there were people’s fireplaces standing in the streets. Old men coughed and spat, women hitched up skirts trailing yellow mud, children ran naked in it as if they were country children. It was like Troyes, and very unlike it. In his pocket he had a letter of introduction to an Île Saint-Louis attorney, Vinot by name. He would find somewhere to spend the night. Tomorrow, he would present himself.

A hawker, selling cures for toothache, collected a crowd that talked back to him. ‘Liar!’ a woman screamed. ‘Get them pulled out, that’s the only way.’ Before he walked away, he saw her wild, mad, urban eyes.

MAÎTRE VINOT was a rotund man, plump-pawed and pugnacious. He affected to be boisterous, like an elderly schoolboy.

‘Well,’ he said, ‘we can but give you a try. We … can … but … give … you … a try.’

I can give it a try, Georges-Jacques thought.

‘One thing’s for sure, your handwriting is atrocious. What do they teach you nowadays? I hope your Latin’s up to scratch.’

‘Maître Vinot,’ Danton said, ‘I’ve clerked for two years, do you think I’ve come here to copy letters?’

Maître Vinot stared at him.

‘My Latin’s fine,’ he said. ‘My Greek’s fine, too. I also speak English fluently, and enough Italian to get by. If that interests you.’